BY STEPHEN MARSH

The late Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini got it right when he said, “Firefighters hate two things—change and the way things are.” Without question, one of the most difficult challenges facing leaders in the fire service is getting members to adopt change in their routines.

- Drawn by Fire: The Disrupters

- They Aren’t Dumb; We Just Gotta Change Our Methods

- Change Is the Only Constant

- Leading Organizations Through Change, Part 1 | Part 2

In many cases, when we are first introduced to innovation, our first reaction is cynicism. This doubt is often rooted in good cause as our well-being and the lives of others frequently depend on the tools and techniques we use. As technology permeates the fire service at an unprecedented rate, leading the membership through change is becoming a critical skill for the modern fire officer.

Without question, one of the most rewarding aspects of being a fire officer is working with different personalities. This benefit is not without its challenges. I used to have a chief who told me the least of my challenges was putting out fires. My greatest challenge would be understanding and then aligning the differing points of view of my subordinates toward a common vision. Five minutes at the firehouse kitchen table will certainly confirm this! When faced with change, every human reacts differently. Understanding and focusing on this uniqueness are key to enacting change within a fire company or organization.

Diffusion of Innovation Theory

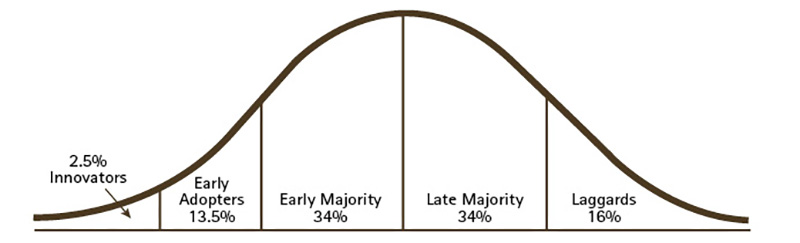

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory was developed in 1962 by E.M. Rogers; it seeks to explain how a population accepts technology. Understanding this theory allows a fire officer to identify how others perceive and assimilate new ideas and technology into their routines. According to Rogers, individuals can be placed into one of five groups based on their feelings toward change.

- The innovators, comprising 2.5% of the population, are eager to take risks and develop new ideas. They need little convincing to motivate toward change.

- The early adopters (13.5%) are comfortable in exercising leadership, accept new ideas, and embrace the opportunity to change.

- The early majority (34%) are comfortable being followers and require evidence that the new process is worthy of their attention.

- The late majority (34%) are skeptical of change and require good information about the new process and testimonials from others who have already tried the technology.

- The laggards (16%) are very skeptical and traditional, requiring strong social pressure and robust data to begin adopting the new technology.1

When viewing this phenomenon graphically, you will note a bell-shaped curve (Figure 1). As a leader driving innovation, understanding that once the first two groups (the innovators and the early adopters) adopt the new technology, the process will usually have enough momentum to be self-sustaining.2 Also realize that as the laggards begin to adapt to new challenges, the process has already begun again—with innovators already beginning to adopt the next innovation.3

Figure 1. Response to Change

Technology Acceptance Model

With an understanding of how individuals perceive and assimilate change, a fire officer can leverage this information to deliver a focused change message. The Technology Acceptance Model was developed in 1986 by Fred Davis; it posits that ease of use and usefulness are the two most important factors individuals consider when evaluating new technology. Combined, these two qualities develop the overall attitude someone has toward incorporating new technology into everyday use.4

When considering ease of use and usefulness, the former bears more weight. If something is perceived as difficult to use, it will receive little further consideration of its usefulness—regardless of how members may accept innovation.5 Think about it—when was the last time you purchased a new smartphone or computer? There’s a good chance when you were at the store, the devices that were hard to use didn’t get more than a few moments of your time. The one you found easy to operate probably piqued your interest and then you decided to devote more time to discovering how useful it was to you. Only then did you decide to purchase it and incorporate it into your daily routine. As a company officer, when introducing change, if you can demonstrate how easy something is to use, you will have a good shot at getting your members to appreciate its usefulness.

Driving Change

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory and the Technology Acceptance Model both explain how people accept change and incorporate it into their lives. With an understanding of these two processes, the next step is getting others to adopt it. Whether it is at the company level or beyond, the process is the same. In Dr. John Kotter’s “The 8-Step Process for Leading Change,” two steps are worthy of a closer look. First, communicating a sense of urgency develops a motivation to act.6 A great place to start is to explain to constituents the reason the change is necessary. As Simon Sinek would say, “People don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.”7 Taking the time to explain to others the reason behind the needed change and listening to concerns will provide a path for a company officer to appeal to ease of use and usefulness and to accentuate the positives. If you have recently been to a car dealership, you’ll have been on the receiving end of this phenomenon.

As a new vision of a cultural norm is presented to people, some may view this as challenging the values they have espoused for many years, especially if the old way of doing things has been working for a long time. Think about how a car salesman creates the urgency to trade in your old reliable car and purchase a new one. How you interpret this process is the Diffusion of Innovation Theory at work!

As a change agent, cultivating trust from people will be critical to affecting the movement that evolves the change. A great way to develop trust in the new vision is to involve people in the change process. Instead of the old-school “Do as I say” approach, using a collaborative style where discussion, debate, and participation are welcomed will cultivate buy-in.8 Although this process takes more time, effort, and patience on the part of a change agent, the buy-in and trust developed will pay dividends going forward.

As the movement toward change begins, recruiting people who are aligned with your cause will greatly assist in communicating and motivating others to move toward the desired vision. It is nearly impossible to enact cultural change in an organization on your own. The adage “Surrounding yourself with good people” is key to advancing a vision. Constituents who are willing to learn new skills, embrace change, listen, embrace new viewpoints, and contribute ideas and who are trustworthy will aid greatly in change.9 Appealing to the innovators and early adopters of your group is a good place to look for people aligned with these ideals.

Trust and Communication

The importance of trust among firefighters cannot be overstated. When fighting against the forces of nature, the bonds of trust that exist between members are essential for everyone’s survival. When driving change, it is equally important for leadership to ensure this bond is nurtured. At its core, cultural change is a challenge to espoused beliefs, artifacts, and assumptions that an individual or group uses to define themselves. In other words, as a change agent, you are asking them to change or give up something they may have held for a long time. Depending on where that person falls on the innovation curve, motivating change may be a formidable challenge. The amount of trust an individual or group has in leadership will be directly proportional to the acceptance and implementation of a new vision.

As a leader driving change, cultivating the bonds of trust that exist between you and subordinates or others involved in the process is critical. A major factor that contributes to a successful change is how well the process is communicated.10 Although communication of vision is important to providing direction, affording members the opportunity to ask questions; share concerns; and share information up, down, and vertically within the organization provides an avenue to cultivate the trust essential for change. Moreover, this process also provides an opportunity for leaders to receive feedback to assess how well the change is being received and enacted. If necessary, this information may then be used to refine aspects of implementation. As was stated previously, affording people the opportunity to develop a personal stake in the change process is a powerful method for successful implementation.

The Diffusion of Innovation Theory, in conjunction with the Technology Acceptance Model, aids leadership in understanding the psychology behind implementing organizational change. They also provide leadership insight for how challenging obtaining member buy-in to a new vision may be. For organizations that are steadfast in their values, small changes may be as challenging as a large change in a progressive organization. The degree of change required combined with the existing organization culture will determine the effort required of leadership.

Armed with an understanding of how an organization will receive a new vision, the leadership can then leverage implementation strategies that create movement; develop a guiding coalition; and, most importantly, leverage communication to develop trust among organization members. Creating an environment where information flows freely nurtures the bonds of trust that are essential to the mission of the fire service.

Endnotes

1. LaMorte, MD, PhD, MPH, W. (٢٠٢٢, November ٣). Diffusion of Innovation Theory. Behavioral Change Models. https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mph-modules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/behavioralchangetheories٤.html.

2. Braddlee, & VanScoy, A. (2019). Bridging the Chasm: Faculty Support Roles for Academic Librarians in the Adoption of Open Educational Resources. College & Research Libraries, 80(4), 426-449. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.80.4.426.

٣. Okoli, T. T., & Tewari, D. D. (٢٠٢١). Does the adoption process of financial technology in Africa follow in inverted U-shaped hypothesis? An evaluation of Rogers diffusion of innovation theory. Asian Academy of Management Journal and Accounting & Finance, 17(1), 281-٣٠٥. https://doi.org/١٠.٢١٣١٥/aamjaf٢٠٢١.١٧.١.١٠.

4. Siwale, M. (٢٠٢٢). Applying Technology Acceptance Model to measure online student residential management software. Journal of International Technology & Information Management, 31(2), 22-47. https://doi.org/10.58729/1941-6679.1547.

5. Zhang, W., & Liangliang, L. (2022). How consumers’ adopting intentions towards eco-friendly smart home services are shaped? An extended technology acceptance model. Annals of Regional Science, 68(2), 307-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-021-01082-x.

6. Houk, K. M., Bartley, K., Morgan-Daniel, J., & Vitale, E. (2022). We are MLA: A qualitative case study on the medical library association’s 2019 communities’ transition. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(1), 34-41. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2022.1225.

7. TEDx Talks. (n.d.). Start with why — how great leaders inspire action. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u4ZoJKF_VuA.

8. Hubbart, J. A. (2023). Organizational change: Considering truth and buy-in. Administrative Sciences, 13(1), 3-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13010003.

٩. Wheeler, T. R., & Holmes, K. L. (٢٠١٧). Rapid transformation of two libraries using Kotter’s eight steps of change. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 105(3), 276-281. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.97.

10. Ahmad, F., & Huvila, I. (2019). Organizational changes, trust, and information sharing: an empirical study. Aslib Journal of Information Management. 71(5), 677-692. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2018-0122.

STEPHEN MARSH is a 25-year veteran of the fire service. He began his career as a volunteer with the Quakertown (NJ) Fire Company and is currently a captain with the Cherry Hill (NJ) Fire Department. His education includes a master’s degree in public administration, a post-master’s certificate in organizational leadership and decision making, and several National Fire Academy courses. He is also credentialed by the Center for Public Safety Excellence as a fire officer.