By JOHNNY TORGESON

The fire service is built on teamwork; it permeates every aspect of the job. From washing the rigs to emergency incidents, everything revolves around a joint effort to meet daily goals and objectives. The fire service is truly all about teamwork, especially as it relates to the timely and critical nature of emergency incidents. In light of this, it raises the questions, What is a team? How do we develop one? and What does the process look like?

- Drill of the Week: Team Building Drills For The Engine Company

- Building Effective Teamwork

- Unit Cohesion: The Company Officer’s Guide to the Ultimate Killer of Low Morale

- TEAM BUILDING DRILLS FOR THE ENGINE COMPANY

This article will give a fresh perspective on team development. It is based on my education, research, training, and experience and provides an alternative to age-old concepts on team development that are taught in many institutions and imparted within fire officer development courses across America.

What Is a Team?

Most define a “team” as a group of people who work together to achieve a shared purpose. This is a great textbook answer and gives most people an understanding of what a team is compared to a “group” of people. However, pragmatically, the definition falls short; a team is much more than this, much more than a shared vision. This definition doesn’t capture the essence of what a team is, especially as it relates to the fire service.

Picture this: An engine or a truck company has intracrew conflict because a newly promoted captain was assigned to the crew. The new leader was not the person the crew wanted promoted, and now they’re stuck with him. Does this sound familiar? How about a crew that stays in their bunk room most the day, doesn’t eat or work out together, and does the bare minimum training hours each month? Does this sound familiar? These are just two examples of many different types of groups or crews that pervade every department. Although they run emergencies together, would you call these engine/truck companies a team?

In the fire service, we work on many types of teams such as cross-functional, specialized, self-managed, leadership, and project. Teams can be large, medium, or small. Those who work shift schedules, such as firefighters, work simultaneously on large, medium, and small teams. The organization is a large team; their shift assignment is a medium-sized team, and the crew to which they are assigned is a small team.

When we use the word team in this context, it is a noun. However, achieving the goal of becoming a team is more than a noun—it is a verb. In our context, a team describes an end-state achievement or type of group actualization based on what a team does and achieves. A group of people working toward a shared vision can still work autonomously from each other. This means there is a second tier between group and team.

We are led to believe that there are only two distinctive collective types, which are groups and teams. This is because it is believed that teams are created in stages instead of forged in phases. This mindset, coupled with how a team is defined, leads to a missing type of collective. The military and fire service have used the term “crew” for many years. Thus, I would like to propose the term “crew” as an intermediate step between group and team.

A group is a collective of people who lacks a shared vision, engagement, and communication; has member skills that are not complementary; instills distrust; and is in perpetual conflict. Not all of these elements have to exist to be a group, but any mix of the aforementioned are well-known distinctives. Alternatively, a crew is a collective of people who have a shared vision, much like a team, but also have many of the same attributes or shortfalls of a group. This is the collective type most departments operate with.

A team, on the other hand, has a shared vision but is also collaborative, is innovative, has complementary skill sets, synergizes, continually improves, holds each other accountable, and effectively meets goals. For the fire service, teams have each of these attributes but also love and care for one another. It is why we use the terms like “brotherhood” and “sisterhood.” Our teams work differently; thus, they look much like a family.

A team that operates like a family has a better capability to optimize. This is because egos dissipate. Empowering, challenging the status quo, and serving one another are commonplace for teams that operate as a family. Any collective group within the fire service who does not look like a family and optimize performance under a shared vision is not a team. This is why fire service leaders must take an honest assessment of their collective group (“Am I operating with a group, crew, or team?”).

Forging a Team

We have been taught that teams are created. Instead, I propose that teams are not created but forged. Forging describes a forming process of raw materials and is typically a process of molding a material into an effective and useful tool. In this metaphor, people are the raw material. Their personality, skills, characteristics, and behaviors are what constitute them, like raw ore. The fire service leader is given a bunch of raw materials that must be heated, formed, cooled, and finished. Thus, fire service leaders are more like blacksmiths, forging with the material given to them. They shape material (people) to be a useful implement and mold a team with what they have, not what they have created.

Although this is a play on syntax, it establishes a clear distinction within the process of becoming a team. Creating a team from scratch doesn’t happen very often, especially in the fire service. More times than not, leaders are given a group or team that has already been established; they aren’t creating new ones. Therefore, whether we view it from an individual perspective of behaviors, skills, and abilities or a collective perspective of established work groups, teams are molded and forged, not created.

Team Optimization

You may have noticed that I keep using the word “optimizing.” This is because creating a high-performing team is a “pie-in-the-sky” goal. People are incapable of performing at a high level all the time. No one is motivated all day, every day. Moreover, a plethora of external influences hamper team performance on a regular basis. Each team member’s performance will be inhibited at some point because of personal matters that pop up in their life. Additionally, there are also many team dynamics that affect a team’s ability to perform at a high-level such as workload, staffing, bureaucracy, and implementation of new technologies that impede team performance. Each are hurdles with which the team must constantly deal. The frequency of each of these factors means that the team leader is always working to improvise, overcome, and adapt.

In light of this, creating a high-performing team is not a realistic goal. A realistic goal is forging an optimum team. This will account for the innumerable amount of variables that hamper continued team performance. Forging a team that is nimble should be the overarching goal of any leader. The team that optimizes can adapt to internal and external forces. It performs at optimal levels in light of the stressors it encounters.

For example, let’s look at the impact COVID-19 had on many teams. During this time, teams were told to “social distance.” Crews at fire stations were asked not to eat together, train together, or have any social interaction that was not emergent. COVID-19 created incredible road blocks to leading a high-performing team in the fire service. During that time, I was a station captain. Maintaining morale and keeping the crew safe were my paramount concerns. When we compare this to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as a leader, I was more worried about the psychological and physical safety of the group than maintaining group actualization and maintaining high performance.

In the early stages of the pandemic, there were so many unknowns and strict rules to follow; this made it impossible to maintain a high-performing team. Firefighters were sick, there was a tremendous amount of overtime, and team dynamics were destroyed because of social distancing. Thus, our team was in disorder, and the fabled high-performing team was nowhere near running at full steam. All I could do as a leader was optimize team performance. Keeping this example in mind, the goal should always be to optimize team performance based on the many factors that affect it.

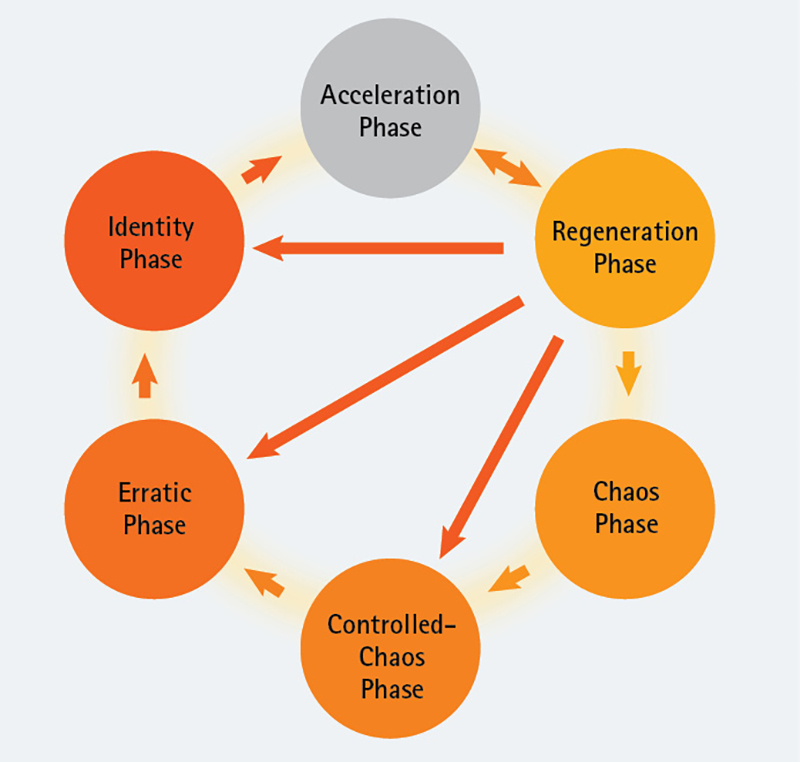

Forging an optimized team must go through a process. The process is cyclical and can be identified through six phases. The six phases involved in forging a team follow:

- Chaos Phase,

- Controlled-Chaos Phase,

- Erratic Phase,

- Identity Phase,

- Acceleration Phase, and

- Regeneration Phase.

Phases of a Team

Many of us have been taught that creating teams happen in stages such as forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning. Instead of viewing the process of team development as stages, it should be viewed as phases; this is because stages are a linear process, such as climbing the rungs of a ladder, while phases are cyclical. Team development is a dynamic process that should account for internal and external factors because teams do not stay stagnant. They instead cycle through recurring phases dependent on a cornucopia of fixed factors and variables. Moreover, groups, crews, and teams will progress and regress into different phases multiple times throughout its existence.

Figure 1. Team Development Phases

Figure by author.

Chaos Phase. When a crew goes through major changes, such as in formal leadership, new crew members, or a new crew mission, there is chaos within the group. The group is in disarray because major changes create unknowns for its members. In the Chaos Phase, various crew dynamics are interrupted and must be restored such as establishing new behaviors, creating or reestablishing a culture, recognizing or providing expectations, and forming or reforming a crew identity. The Chaos Phase is also characterized by distrust and resistance from its members who are resistant to new leadership, change, and production. Sometimes, this leads to sabotage from within the group. Truly, this is a difficult phase for all of the members, especially leaders. The phase can last up to six months, depending on several variables.

Controlled-Chaos Phase. From the Chaos Phase, the group will transition into controlled chaos. Although this seems like an oxymoron, it is the best way to describe the transitional period between chaos and the group entering into an erratic phase. In the Controlled-Chaos Phase, the leader of the crew starts to establish a small amount of influence and lays the groundwork for new group structures. In light of this, the chaos starts to subside but is not removed; it is merely controlled. This is because a lot of the unknowns are now known, but the group is still lacking trust, a shared vision, and a group identity. However, the group is now finding ways to work and deal with their new reality. This phase lasts three to eight months, depending on leadership ability.

Erratic Phase. The Erratic Phase is a tipping point. In this phase, the group has a shared vision and is transitioning into a crew. As a crew, they will begin to generate an identity that most members will recognize as separating them from other groups, crews, or teams. However, not every member is buying into the identity of the crew during this phase, and those who are buying in aren’t consistent with their behaviors because intracrew accountability isn’t established or is inconsistent. Nevertheless, the crew is stacking small wins and productivity is improving.

The distinction of this phase can be recognized by the erratic nature of its success. There will be moments of achievement but also not as many moments of failure. The leader and crew members will recognize that there is a lot more work to do to become a team. This is the phase in which many leaders become stuck because external factors create roadblocks, crew members come and go, personal issues arise, and bureaucracy grows, all of which have a significant influence on becoming a team while creating an erratic environment. This phase will typically last six months, but it can also continue indefinitely.

Identity Phase. This is a transitional phase between the Erratic and Acceleration Phases. In this phase, 100% of the members have bought in to the identity of the crew and are now becoming a team. There is a shared vision, and members are holding each other accountable based on the team identity. Anything that members do in contrast to the team identity gets dealt with by the crew members and not the formal leader of the team. Members also build each other up and collaborate on projects. The team rallies behind their new identity. This phase is the main reason having a team identity to unite behind is so important; it creates a team distinctiveness that drives accountability and “esprit de corps.” As an easy litmus test, if you don’t have a team identity, you don’t have a team. This phase lasts from one to three months.

Acceleration Phase. This is the fun phase, but it is also fleeting. In the Acceleration Phase, the fledgling team transitions into an optimized team and is now functioning as a cohesive unit. The team is improving every day at an accelerated rate. Members are growing as individuals and the team is growing as a unit. Productivity and performance are an everyday occurrence. Most importantly, the team has a tremendous amount of job satisfaction; in fact, it’s palpable by every member, and the team is now able to overcome small challenges and still stay effective. Thus, the team is able to optimize. However, this phase is also sporadic and transitions back and forth between it and the Regeneration Phase. Additionally, because of the cyclical nature of team development, the phase will last only until there are major changes to the personnel on the team or major challenges that create too much change. There is no greater hurdle a team can overcome than a change in team leadership.

Regeneration Phase. This phase must occur during the acceleration phase and is marked by the team’s ability to perform during the insurmountable internal and external factors that impact its effectiveness. Teams are not able to sustain high performance indefinitely. Thus, this phase represents a team working back toward the Acceleration Phase and overcoming challenges. The team must regenerate to reach the Acceleration Phase after substantial changes or problems. In this phase, a large amount of momentum has been lost, and the team must stack small wins and absorb losses. Any losses or changes from which the team is unable to recover puts the team into any one of the phases to start over again. Thus, if a team cannot regenerate, it may degenerate back into a Chaos (or any other) Phase, depending on the amount of change and instability within the team.

Carry the Torch

The fire service has built a lasting and historic legacy because of its ability to forge teams. However, the world is changing along with its values. In light of this, the leaders of today’s fire service must adapt with the change. Meet challenges head on and optimize team performance. Forging your team requires you to understand, at the very least, team constructs.

It is incumbent on us to carry the torch and be just as effective as our fire service forefathers. To do this, leaders must know how to forge optimum teams; distinguish what a team truly is; and understand the cyclical nature that exists among groups, crews, and teams. Improve the legacy views on leadership, management, and team development from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s with fresh perspectives, which can face contemporary challenges. By doing so, we will leave the fire service better than we found it and will continue the rich legacy that was bestowed on us.

JOHNNY TORGESON is a 23-year fire service veteran and the assistant chief of operations for Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow Fire & Emergency Services. He is a fellow for the Lejeune Leadership Institute and a fire academy instructor for Copper Mountain and College of the Desert community college. He has a doctorate in strategic leadership and is authoring a book on team development.