Training Notebook | By TIM PILLSWORTH

Whether you like or dislike the idea of battery-operated devices, they are here to stay and will continue to increase in popularity. To reinforce this, walk into any home goods box store and look at the lawn mowers and other lawn tools; for the most part, they are all battery operated, and very few are gas powered. We can learn much from history and how it affects today’s firefighting tactics and how to adjust and correct them for the future.

- Training Minutes: Electric Vehicle Hazards

- EV Size-Up and Thermal Runaway: Lucid Air

- Electric Vehicle Fires: What’s Really Going On?

Ten to 15 years ago, there were reports of smartphones overheating while charging. In many cases, they were plugged in, they were placed under a pillow (teenagers were hiding them at night), and they burned the sheets. Yes, there were some fires but, thankfully, nothing to the extent we are seeing now and will into the future. The batteries were small; did not draw much power; and, for the most part, did not have a high risk.

A few years ago, after Christmastime, there were all the warnings on charging the newest “it” gift: electric hoverboards. If you have one, don’t leave it unsupervised or plugged in for prolonged periods of time, as reports of fires occurring in homes, single-family residences, and some city high-rise buildings from these charging are increasing. As with many of the battery-operated devices, they are plugged in and are left to charge. In years past, the “it” item was a cell phone or laptop. For the most part, there were not many issues with them, mostly because of their overall size and the amount of energy stored within their batteries. However, there are cases of failures that exist with computers, phones, and e-cigarettes (photo 1). Now, with larger and more powerful battery systems, things have changed; it is not if but when and how bad the runaway battery/fire incident will be.

Fast-forward a decade, and there are now lithium-ion batteries in almost any device, from computers to tools to luggage, with warnings not to pack them in checked luggage at the airport. The Federal Aviation Administration is always out in front on these issues, creating warning labels that most of us never read.

(1) A computer battery expanding because of age/damage. (Photos by author.)

(2) A roof truss sign.

So, what have we learned? Not much. Although many fire departments have perhaps talked about the issue, do they have a planned response for an electric vehicle (EV) fire, one alongside a road? What about a fire in an attached garage of a house? Or one involving an electric scooter charging in grandma’s house? A quick online search shows there are more than just a few news reports and videos from around the world on thermal runaway batteries that caused fires within homes. Almost weekly in my local area, the Fire Department of New York responds to reports of fires caused by lithium-ion batteries, sadly leading to injuries and deaths. What will you do when your department is dispatched to a lithium-ion battery fire in a home or an attached garage? What if it involves an EV or a building power backup unit on fire?

Our job as firefighters, leaders, and departments is to prepare for the emergencies to which we respond. So, do you have a plan or a message to the public? Can you use code compliance to help with this, now and into the future? Working in reverse order, code compliance is very much a long-term, slow-to-react method. In most cases, the reactions come after events—they are 100% reactive. Thirty years ago, when the new truss roofs and floors began injuring and killing firefighters, many municipalities started to require signage on both commercial and multifamily residential buildings with truss roofs prominently placed (photo 2). This was a symbol to command that there was now a high risk of structural failure early on in the firefight. Some proactive communities now have signage on their entrance roads with this information.

Looking forward, it could be a best practice to place a sign on the mailboxes of homes that have EV/charging units or an entire battery backup in the garage. There could also be a building permit requirement to install the charging unit (if installed properly). Proactive firefighters and chief officers takes mental and written notes on these possibilities when traveling around their first-due area.

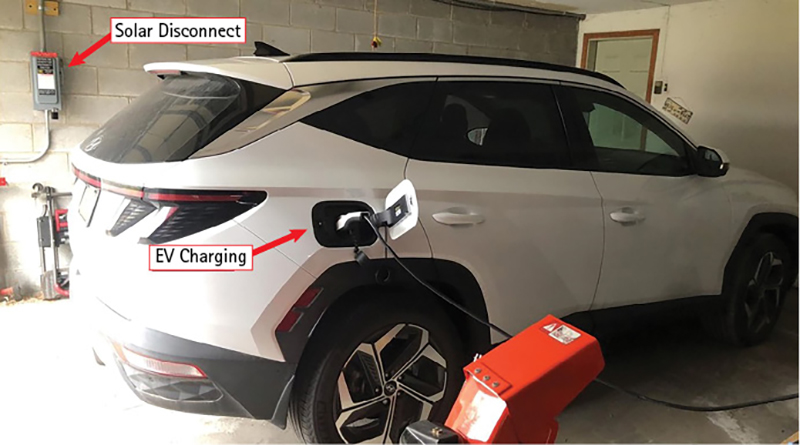

From my experience, more and more of us know a neighbor or friend (photo 3) who has purchased an EV and charges it in his garage. If this is you, go over to his house and check out how the system works. Does it plug into a standard outlet (Level 1 charger)? Is it a quick-charge/Level 2 unit, similar to those you see in parking lots (photo 4)? This information is usually not shared with the EV purchaser, and some charging issues as well as knowledge shared with the end-user side could help protect the resident if a fire ignites.

If a fire does occur with that electric hoverboard, scooter, or skateboard, what is your game plan? Although they are much smaller than an EV, they are often stored and charged within the indoor living space. The devices could/would ignite other items within the room or block the exit path from the room, home, or dorm room. But what about the battery in full thermal runaway?

A great video from England in winter 2022 showed an electric scooter fire releasing pressure in much the same way a propane tank’s pressure relief valve would if exposed to high heat. If you arrived to such a fire and had to give a size-up, what would you say? The device could ignite other items in the room that would then need to be extinguished with water. Will we need to bring in a Class D extinguishing agent or foam to finish off the battery? Not completely—it is a runaway electrical short circuit that will not completely extinguish with a hose stream from our handlines. Do we flood the home and cause unnecessary damage? Maybe. Will your crews be able to think outside the box?

Next, consider overhaul and salvage. Once “out,” how do we remove the battery-operated device to the exterior to preserve the building and, more importantly, ensure our safety? If something has a high probability or even a chance of reigniting, remove it from the building’s interior as early on as possible.

These devices are an electric power source, so can they be dragged out of the building with a hook or halligan? Halligans are metal, which we know conducts electricity.

Online, many sites discuss this type of event, but they never talk about how to remove a thermal runaway battery once it is out. This could be alleviated some by industry-issued guidelines to help assist responders. For instance, we could wrap the device in a fire blanket (there are now lithium-ion battery fire blankets) and get it out a window. This is an issue the fire service needs to figure out, so think outside the box for solutions before there is an event.

Scenario #1: MVA

In February 2022 in Rockland County, New York, a motor vehicle accident (MVA) occurred, with the subsequent fire involving an EV. The battery bank that took up the vehicle’s entire floor was damaged, causing a thermal runaway. This fire took our fully committed fire department hours to completely extinguish. The roadway was shut down, and mutual aid arrived to supply water. The EV was lifted by a crane wrecker and placed in a watertight box, and the box was then filled with water. With less water comes, more likely, less time. However, not many departments have these boxes, nor do they know how to move it once the battery is extinguished; I am unaware of any parts of the United States that are set up for responses like these.

In EV numbers, Europe is ahead of the United States. Some European cities have dumpsters that are watertight. At an EV fire, the EV is lifted by a crane wrecker, placed in the box, and the box is then filled with water. (Great! Less water, more likely less time, but who has one, and how do we move it once it is out? However, I do not know of any area of the United States that is set up for this, yet.) Once the fire is “out,” the EV is taken to a wrecking yard. If left in the open air, the thermal runaway can reignite days later. Does the owner of the wrecking yard know that? We must inform him to set the EV far away from others in his lot. This incident can easily go from a one-car “fire” to an entire lot or more on fire. That is not the way you want to end up on the 6 o’clock news. With less water comes, more likely, less time.

Scenario #2: Garage Fire

Our next scenario, one that should be even more concerning, is an EV fire in the garage of a residence. All the problems from the above scenario exist, but now add a family’s home to the mix. We can extinguish it with water, but we cannot know if or when it will ignite again. The amounts of heat and toxic gases that were once outside are now on the interior. If the fire is still burning on arrival, has the garage self-vented? Can you get the EV out of the garage and, if so, how? Drag it out with a fire department vehicle with a chain or strap? Nylon will melt, but a metal chain or cable can be a conductor to the 200 to 800 volts still within the EV.

Next, ask yourself, what is my water supply in the area? A hydrant or tanker/tender? From many reports, to fully control some EV fires, 30,000 or more gallons were needed, which equates to 10 loads from my department’s tanker. That is a lot of water. Some planning prior to an emergency will help in the event of this type of emergency. The gases given off by EV batteries, including carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen cyanide (H2S), and hydrogen (H), are highly toxic and flammable and can explode if venting is not done correctly or the gases do not self-vent.

In 2019, research on these fires was conducted at an energy storage facility in Peoria, Arizona. The explosion only injured four firefighters, with the word “only” being used because of the small size of the fire crew, so it could have been much worse.

The need for full self-contained breathing apparatus and personal protective equipment cannot be overstated. To be successful, we first must get the fire under control, with “under control” being different than “out.” Most likely, we will not get it out on the first try, so how do we protect the home for our residents? Can we call in a wrecker or fire department vehicle to drag out the EV outside or into the driveway? Many fire departments have tools to complete this task, but it is now a question of safety. If the fire takes place in a nonhydranted area, you must call for tankers early.

(3) An electric vehicle charging in a garage and a solar disconnect.

(4) A public fast-charging station.

As time moves forward, some homeowners take self-sustainable and green energy to the next level in the form of full-home battery packs. Simply, these are battery systems very similar to the batteries found in an EV, but they are mounted on the wall inside the home and are meant to supply the home with power if there is a loss of line power (e.g., from a storm) and do not require a gas- or propane-fired generator. Many times, a solar array is also mounted on the roof to help supply power to the system, which houses an uninterrupted power supply (UPS). These packs do not pose any CO issues and are on standby all the time. They do, however, pose similar concerns to an EV in a garage, but we cannot just pull the pack from the home. The feed from the solar array may be sending power as it burns, or it simply cannot be turned off (controlled) to allow for safe extinguishment or removal. If so, then what? As before, having a sign on the mailbox alerting crews to this would be beneficial.

More businesses are installing stand-alone energy storage facilities, similar to home battery backup systems, within their properties. These can act as a UPS for important computer and data systems and load shedding during peak electric usage periods. The fires in Chandler and Peoria, Arizona, have shown that these facilities exist and unless there is local knowledge, the fire department might not be aware of their existence until it is too late. Underwriters Laboratories’ Web site features training information on the Peoria incident that shows the dangers and limitations of the designed suppression system. Most interesting are the many systems designed to hold off the fire for 10 minutes. However, the thermal runaway can continue to burn for hours or even days; it all depends on the size of the battery bank and the amounts of stored energy.

The fire service and local building and fire codes are underprepared for upcoming events regarding thermal runaway batteries. Departments may have the tools on hand to address many of these emergencies above, but we need assistance from the manufacturers to further train and offer the best protection we can to our communities.

Pressure your community leaders to create a building code requiring the posting of the presence of EV and full-home charging systems in your area. Many manufacturers do or would not want to accept that their product poses any danger to the public and continue to push out more systems. We must hold them responsible to supply the information we need to protect our communities and fire department members.

To improve your response, speak to your membership and neighboring departments and gain knowledge from research. Research product information for lithium-ion battery blankets. Also, talk to your local code compliance officials and see if there is a way to track permits on charging stations, UPSs, and solar installations. You can add this information to your computer-aided dispatch system. Be proactive; it is not so much as an if but when you will respond to one of these fires.

TIM PILLSWORTH is a 37-year volunteer fire service veteran, a firefighter/EMT with the Washingtonville (NY) Fire Department, and a past chief and life member of the Winona Lake (NY) Engine Company. He has presented at FDIC International and at other local and regional conferences on engine company operations and leadership in the volunteer fire service. He authored and coauthored many articles on PPE, volunteerism, engine company operations, attack system flow testing, and volunteer fire department management and planning. He is the author of the PPE chapter in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II. He is a project engineer for the Army Corps of Engineers at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.