By David J. Dubowski

Photos from private collection of author

On July 12, 1973, a major fire broke out on the sixth floor of the National Personnel Records Center in Overland, Missouri. At the time of the fire, the Records Center, located in suburban St. Louis, was only second in size in the United States to the Pentagon in square footage related to building size. The fire would grow to nine alarms and is still considered the largest fire to occur in St. Louis County to date. Fifty years later, government archivists are still challenged with finding and restoring lost records from the devastation of this historic fire.

The Military Personnel Records Center was constructed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers at a cost of 12.5 million dollars. The 1,569,332 square foot, six-story structure was occupied in 1956 to store military personnel records. At that time, most records were stored in metal fire cabinets which provided greater fire protection than files stored on steel shelves. During the facility’s construction, many archivists feared the potential of water damage from sprinkler malfunction, which outweighed any fire damage concerns to the files. This oversight led to thousands of documents being lost and/or damaged.

- Building Construction Review for Firefighters

- How Does a Fully Sprinklered Warehouse Burn to the Ground?

- Tom Dunne: Managing Big Fires 101: Divide and Conquer

- The Mutual-Aid Plan: More Than Words on Paper

In 1960 the General Services Administration (GSA) assumed control over the building. Sixty percent of the building was used for storage of the 1.6 million cubic feet of military records while the rest of the building was office space for clerical and administrative staff.

TYPE OF CONSTRUCTION/SYSTEMS

The superstructure of the six-story, 282-foot x 729-foot building was standard skeleton construction of reinforced concrete, using conventional eight-inch flat slabs on spirally reinforced square columns spaced 22 feet and four inches on center throughout floors one through five. The seven-inch-thick roof slab sat on the sixth floor, supported by 16-inch reinforced square-tied columns. Of significant note, there were no fire partitions or breaks on the sixth floor. To put the size of the building in perspective, each floor was as large as six football fields. The entire building was of Type 1 construction with noncombustible, protected beams and columns with a sprinkler system.

Before the GSA assumed control of the building in 1960, about 65% of the first and 35% of the second floors were equipped with a sprinkler system. The GSA first proposed automatic sprinkler protection for the rest of the building in 1963 and it was approved by Congress the following year. However, GSA did not fund the project. Available funds were used on projects the GSA considered to be a higher priority.

Smoke detectors were installed in the air circulation system, which served only the office areas. The building had no exhaust system for removing smoke in an emergency. A local evacuation alarm was installed throughout the building. A Class III, wet standpipe system was provided with 1½-inch hoses for occupant use and 2½-inch connections for fire department use. Water was supplied by a 12-inch hydrant loop surrounding the building. A 250,000-gallon reservoir was also provided, from which a 1,500 gpm automatic electric fire pump took suction and discharged into the hydrant loop.

HISTORY OF OTHER EVENTS

From May 1972 until the major fire in July 1973, nine fires were reported inside the Records Center. Of these, seven were in restrooms, one in a trash container. The other was a mop fire in a fifth-floor custodial closet just six days before the major fire that destroyed the building on July 12, 1973. Of these nine fires, six were suspected of being intentionally set and were investigated by the FBI.

It was agreed that the situation was dire and all possible means should be taken to identify the person or persons who had been setting the fires. A letter was drafted to all employees asking for their cooperation in getting information that might lead to the apprehension of a suspect. Unfortunately, insufficient evidence was uncovered to justify the identification of any individual who may have been related to the previous suspicious fires.

THE CALL CAME IN

Just after midnight on Thursday, July 12, 1973, a man leaving his place of work in neighboring Olivette, Missouri, observed fire through the windows of the sixth floor of the Records Center. He asked his boss to call the Olivette Fire Department. Meanwhile, this man drove to the Records Center and informed Federal Protective Officer (FPO) Dewey Richard of the fire noticed on the sixth floor. FPO Richard went to the southside of the building, saw the flames on the sixth-floor windows, and notified his supervisor, FPO Sergeant Hamilton.

At 00:16:15 hours, North Central County Fire Alarm System, the primary dispatch agency for several suburban fire departments, received a call from the Olivette Fire Department reporting a fire at the Record Center. Twenty seconds later, North Central received Sergeant Hamilton’s direct call from the Records Center, reporting a fire on the sixth floor.

Responding Agencies

At 00:17:25 hours, North Central dispatched the Community Fire Protection District to an F-2, indicating an assignment for a commercial building fire at the Record Center at 9700 Page Avenue. Responding companies were Pumper 205, Pumper 204, Ladder 209, Emergency Truck 208, and Ambulance 207, totaling 12 firefighters.

CONDITIONS FOUND

At 00:20:35 hours, Pumper 205 and Ladder 209 arrived on the scene and were met by a security guard at the main entrance to the building on Page Avenue. The guard informed Captain Pete Garey of a fire in a fourth-floor restroom. Captain Garey and Firefighters Klein and Miller proceeded to the fourth floor via stairway A. Upon arrival on the fourth floor, members observed smoke in the escalator lobby. There was heavy smoke in the restrooms, but no heat or fire was reported. Captain Garey contacted Deputy Chief Bud Zaiz via a direct phone line to the guard’s desk in the lobby and informed the chief of their conditions and that they were headed to the fifth floor to investigate for smoke and fire.

At 00:30:00 hours, Deputy Chief Zaiz struck a second alarm bringing in Community Pumper 211 and Olivette Pumper 271. At 00:30:45, a third alarm was struck, bringing in West Overland Pumper 251. One minute later, Assistant Chief James Kennedy was requested to the scene. Kennedy would become the incident commander (IC) for the duration of the fire. (Chief of Department John Gertken was out of town at a conference at the time of the alarm.) At 00:33:55, Ladder 209 reported to Deputy Chief Zaiz: “We’ve got a major fire on the sixth floor, major…gonna need at least one more ladder truck, and you better send two, about half of the building is going.”

Upon reaching the fifth floor, crews discovered heavy smoke but no heat. Not having a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), Captain Garey remained on the fifth floor while his two firefighters proceeded to the sixth floor. Upon opening the door on the sixth floor, the two firefighters investigating without a hoseline were met with a blast of heat and saw an orange glow. Both firefighters left the sixth floor and returned to the fifth floor. Unable to locate Captain Garey, Firefighter Klein located a telephone, dialed 9 for an outside line, and called North Central dispatch with the report to “notify the deputy that we have extreme heat and smoke on the sixth floor, and we need some help.”

Another firefighter soon arrived and joined the original crew of Klein and Miller and reentered the sixth floor. This crew stretched the 1½-inch hose cabinet line and charged it. The crew made their way to the east door of the escalator lobby with the charged line. They opened an interior door on the sixth floor and were met by unbearable heat. They were only able to flow their line for 10-20 seconds before having to retreat to the fifth floor.

Deployment/Decisions/Actions

Over the next four hours, firefighters worked through intense heat and smoke with no success in controlling the flames. The West Overland Pumper 251 crew, led by Acting Captain Larry Meredith, also made their way up to the sixth floor and attempted to open an interior door. Meredith stated: “It was like looking out into a furnace.” He also said: “It (the water) was steam by the time it got to the fire.” Several air cascade units were requested to the scene as firefighters began to run low on air. One firefighter described as “very sick” was transported via ambulance to St. John’s Hospital in St. Louis County.

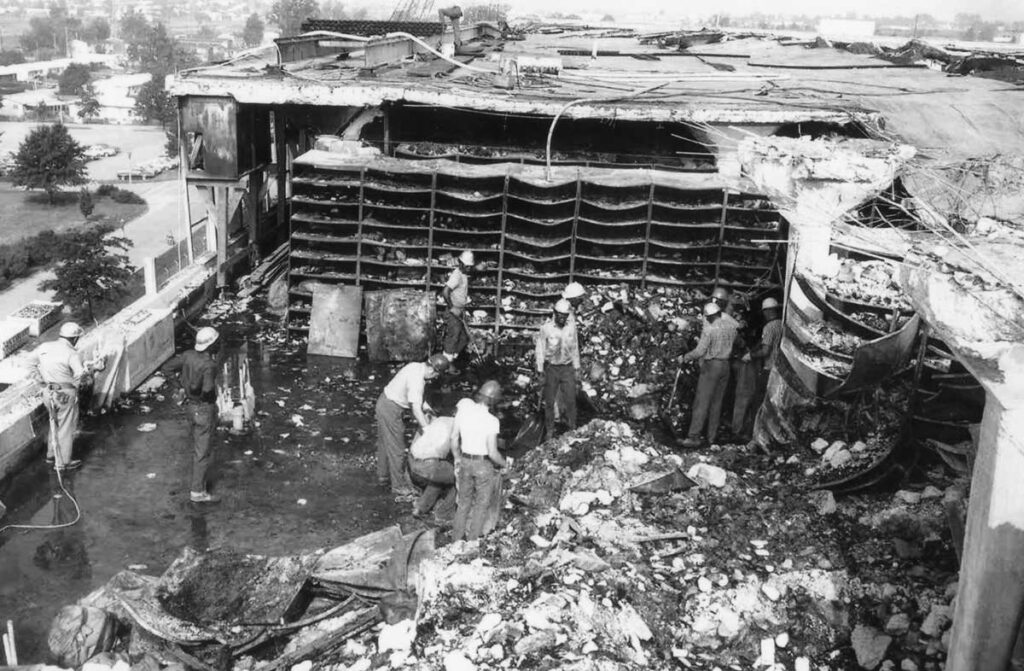

At 04:54, Deputy Chief Zaiz ordered “everyone down and out of the building on the double.” It was determined that current attempts had been unsuccessful and it was time to reassess the situation and change tactics. By now, the fifth alarm had been struck, bringing in three additional ladder trucks from University City, Wellston, Normandy, and Creve Coeur’s Snorkel. Within two hours of aerial operations, much of the visible fire from the south side of the building had been darkened down. Firefighters then reentered the building through windows from an aerial truck and attempted to advance hoselines through file racks but were driven back by intense heat and deteriorating conditions. Firefighters described the heat as being so intense that their masks and rubber coats began to melt.

More attempts were made to advance lines from the fifth floor up the stairway to the sixth floor, near the center of the building, but firefighters were again driven back by extreme heat and smoke conditions. Hazelwood Captain Greg Silliman recalled his attempt to make the sixth floor. “We had to pry the door open, the door was extremely hot. Once we got the door open, there were six inches of water on the floor, and the water was scalding hot. And then the water started coming out at us and cascading down the stairwell, and it just instantly filled the stairway up with steam and smoke. The steam was hot, it was intolerable. We had to abandon our plans”.

By that afternoon, firefighters could position deck guns supplied by 2½-inch hoselines on the 6th floor near the north side of the building in the hope of stopping the fire from spreading. But once again, there was little success. The size of the building and the heavy fuel load were significant in controlling the fire.

In addition to the fire conditions, crews had to deal with a typical, hot, and humid St. Louis summer day. Temperatures during the day reach the mid-90s with high humidity. This was another challenge for crews and command staff as the incident prolonged.

DURATION

At about 22:30 on Thursday night, 22 and a half hours into the fire, a large section of the roof structure failed, opening an area approximately 550 feet by 125 feet. The use of seven elevated master streams continued until 10:00 a.m. on Friday morning when the fire was finally brought under control. The fire, however, continued to burn under the collapsed roof until Saturday morning, with small smoldering fires continuing until Monday morning, July 16. At 09:00 on Monday, July 16, 1973, the nine-alarm fire was officially declared “out.” The building was turned over to the GSA four days and nine hours after the original alarm came in.

CHALLENGES

During the Records Center’s first years of operation, the U.S. Army stored the files in steel file cabinets. Guards patrolled the floors around the clock as a fire watch, and hand extinguishers were at close intervals throughout the building. When the GSA took over in 1960, this all changed. The new record storage method was now in cardboard boxes on steel shelving towering nine feet high. The sixth floor alone contained some 21.7 million paper files, many of them at least 25 years old.

In July of 1973, less than 10 aerial trucks in St. Louis County were 85 feet or taller. At the time of the fire, two of those ladder trucks were out of service for unknown reasons. There was no mutual aid agreement between the St. Louis County fire departments and the St. Louis Fire Department. At about 25 hours into the fire, it was determined by the IC that a 100-foot ladder truck was needed from the St. Louis Fire Department. After an early morning phone call to the St. Louis Fire Chief and the mayor of the City of St. Louis, Hook and Ladder 15 was given orders to respond to the Record Center along with the battalion chief of the 9th District.

OUTCOME

Because of the firefighters’ efforts, fire damage was generally limited to the sixth floor, and no serious injuries occurred. Once all the shelving and damaged files were removed, the entire sixth floor was demolished. The six-story building was now a five-story building, and floors one through five survived without major structural damage. The GSA estimated damage from the fire to be $14 million. The Records Center would continue to operate at this site until 2011, when operations were moved to a new, modern facility in North St. Louis County. The new facility is fully sprinkled with state-of-the-art fire protection systems. Today a team of government archivists known as the Preservation Branch diligently works daily on files damaged by the fire from 50 years ago.

*

It is estimated that 200-300 firefighters from 42 fire departments helped bring the fire under control. After the fire, Assistant Chief Kennedy listed several contributing factors that made extinguishment of the fire so difficult:

- Lack of automatic fire detection or fire suppression equipment resulting in a delayed alarm.

- Heavy fire loading.

- Lack of firewalls and fire doors.

- Open escalator shafts that created a strong draft condition.

- No vertical means of ventilation. Horizontal ventilation, such as windows, proved to be of little value.

- Extreme heat conditions made interior attack almost impossible for several hours.

Several theories have evolved as to the cause of the fire. Was it intentionally set? Was it careless smoking? Was it a government conspiracy? Fifty years after the fire, the cause is still a mystery. FBI investigators looked for evidence of arson, but they never determined the fire’s point of origin or time of ignition. After the fire, an emergency request was sent to Congress for approval to install a sprinkler system. Congress approved the request.

References

NFPA Fire Journal, May 1974 Edition

The American Archivist, Volume 37, Number 4, October 1974

GSA Report To The Government Activities Subcommittee On Government Operations, Oct. 9, 1974

David J. Dubowski is a 40-year veteran of the fire service and an engine company captain in north St. Louis County. He is an award-winning fireground photographer and has a strong passion for preserving our fire service history through photography. Dave serves as secretary on the executive board of the F.O.O.L.S. International.