By GREG CASSELL, JON WIERCINSKI, DAVID E. SLATTERY, and KAREN DONNAHIE

On the evening of October 1, 2017, more than 22,000 concertgoers were enjoying the last night of a three-night country music event known as the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas, Nevada. The venue for this event was a 17.5-acre, outdoor lot on the south end of the “Las Vegas Strip.” This venue lay within jurisdictional boundaries of the Clark County (NV) Fire Department (CCFD).

- Training Minutes: Patient Assessment at MCI

- EMS Response to the Active Shooter

- EMS Response to the Mass Shooting at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas

- First-Due Battalion Chief: The 1 October Shooting

What began as a wonderful October evening in the cool desert air suddenly became a terrorizing struggle of life and death. At approximately 10:06 p.m., a lone gunman opened fire on the concert grounds from a hotel suite on the 32nd floor of a resort across the street from the venue. Within a 10-minute time frame, the killer fired more than 1,000 rounds at the concert venue, resulting in more than 800 people being injured, more than 420 of them suffering at least one gunshot wound. The attendees fled in every direction. Most of those injured were transported to area hospitals by means other than emergency medical services (EMS) units, including personal vehicles, cabs, public transportation, rideshares, and other means of transportation to get the care they needed. In total, 60 people died from their injuries.

This was a deliberate and methodically planned attack that shocked not only our southern Nevada community but our nation as well. However, tragic events like this can result in local responders recognizing an opportunity to make changes to how they operate during disasters. This proved to be true on this fateful night.

(1) Victims arrive at an emergency room by private ambulance. [Photo courtesy of the Clark County (NV) Office of Communications.]

Making Changes

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, the CCFD took a long look at how the response went on this tragic evening. Working with our law enforcement counterparts and neighboring fire departments, we learned a tremendous amount in the days, weeks, months, and years to come. One of the most notable lessons learned from this incident was the direct actions of a Henderson Fire Department (HFD) engine company and rescue ambulance.

The HFD is a neighboring jurisdiction to the CCFD. During the time of the shooting, these two HFD units were delivering a patient from a motor vehicle crash to the Level II trauma center. HFD crews were wrapping things up and about to head back to their station when they were caught in the sudden surge of several dozen critically wounded patients arriving at the hospital by both EMS transport agencies and private vehicles. Recognizing what was taking place, they immediately began helping emergency department (ED) staff with patient treatment, triage, and other tasks to handle the 212 victims that arrived in an hour’s time. Their heroic efforts and professionalism in a time of unthinkable human tragedy not only helped save lives but spawned a new response concept for our community. This concept-turned-response policy is now known as Hospital Area Command (HAC).

Policy

HAC is a Clark County policy that has been adopted by the Southern Nevada Fire Operations Group (SNFO). The SNFO includes all seven Clark County fire departments spanning roughly 8,000 square miles. The fire departments that make up this group include the CCFD, HFD, Las Vegas Fire and Rescue (LVFR), North Las Vegas, Mesquite, Mount Charleston, and Boulder City. Formed in 2007, this group has focused their attention on common operating policies for the fireground and other emergencies. SNFO’s monthly meetings to discuss operations and collaborative support have led to a series of standard operating procedures (SOPs) that every fire department supports. HAC is one of those SOPs. As currently written, HAC is used for all mass-casualty incidents (MCIs) that produce more than 25 patients, locally defined as a Level 3 MCI. HAC can be initiated in any of the following ways:

- The notification of a Level 3 MCI (or larger) by the incident commander (IC).

- The request of any fire department unit suspecting a patient surge.

- The request from a hospital by calling 911.

Once requested, the fire communications center will notify area hospitals of a potential patient surge and assign an available battalion chief or other appropriate fire officer to serve as the HAC IC. Given the SNFO collaboration on this policy, the officer assigned to HAC does not have to be from the jurisdiction where the MCI is taking place. When possible, it is preferred that this officer be in quarters and away from the original incident.

Following the establishment of HAC, fire companies are then dispatched to the closest two hospitals and trauma center in relation to the original MCI’s location. If, by chance, a different hospital other that those mentioned before has a patient surge from the MCI, it can call 911 to request fire department assistance. At that point, the communications center will notify HAC that this hospital is requesting assistance. A fire company will then be dispatched to that particular hospital and be added to HAC’s oversight.

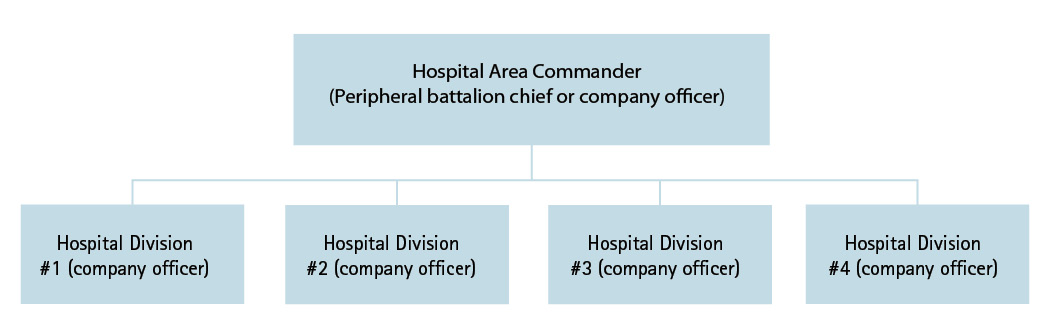

Figure 1. Incident Command System Chart for Clark County (NV) Hospital Area Command

On arrival at their assigned hospital, fire department crews will become a division that reports back to HAC, and their officer will become the division supervisor, who will then contact the charge nurse at that hospital to determine their needs. Once this is accomplished, the two of them will work together to manage resources as needed. At this point, the division supervisor will provide HAC with a conditions, actions, and needs report. If required, the division supervisor can request additional fire department resources to bolster their staffing. Hospitals using fire department support can assign fire department resources to provide field triage in the ambulance bay or other location they deem appropriate, assist in moving patients or equipment, assist in other areas as needed, and provide care up to the scope of their EMS protocols under the direction of the hospital staff.

Training Development

Although HAC was codified in an SNFO SOP by the end of 2018, the opportunity to conduct full-scale exercises to evaluate all the components within the policy had not presented itself. The largest obstacles to conducting exercises were funding, limited staff availability because of workload, and the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

In January 2022, the Clark County Office of Emergency Management (CCOEM) identified a funding source for exercising the HAC SOP. CCOEM staff assembled an exercise team consisting of five personnel: two from the CCFD, two from CCOEM, and one registered nurse from the Southern Nevada Health District. The exercise team successfully collaborated in designing, coordinating, and delivering this training opportunity to 17 area hospitals, including the county hospital, a federal hospital, and all privately operated full-sized hospitals in Clark County.

To help set the stage for a successful and positive training event, the exercise team collaborated with the TV channel production team from the Clark County Office of Communications and the HFD to produce a seven-minute training video. The intended purpose of this video was to prepare participants for the drills and included a simulation of HAC, the arrival of an engine company at the emergency department, and the initial interaction between the company officer and the charge nurse. This video was sent to each participating fire and police department, communications center, and hospital staff. Lastly, a sign-up calendar was created that offered three potential time slots for each day the training was to take place. Hospitals were then allowed access to the calendar so they could schedule the drill at their facility on a first-come, first-serve basis. The training officially began on May 9, 2022, and concluded on May 26, 2022.

Training Delivery and Successes

Training participants for these drills included all southern Nevada fire departments and hospitals. Fire departments were matched with the hospitals within their jurisdiction; the communication centers were also included in each exercise. The scenario used was a simulated patient surge from a shooting at a high school football game. This event produced 25 patients being delivered to the emergency department of the hospital in the exercise.

In a span of approximately 20 minutes, 25 mannequins simulating patients with a wide range of complaints were delivered in four separate waves—to either the emergency department doors or the hospital’s main entrance. The latter drop-off point tested the ability of the hospital to manage patients arriving at either point of entry into their facility.

There were several successes in the training, the biggest of which was arguably the knowledge that this type of supportive response was achievable. During the drills, hospital staff and fire crews built effective teams because of the following:

Simplicity. HAC is relatively simple. Training material and the drill were intended to maintain this level of simplicity by focusing on the interaction of participants and limiting the complexity of clinical interventions and external threat injects. The drill maintained a focus on the coordination and communication between the fire department company officer and ED charge nurse. A real incident of this scale would include several challenges not presented in the training (e.g., a secondary response of family members, security concerns, media involvement, high levels of chaos, and noise).

Training was tolerable for hospitals. At the time of the drills, many of the participating hospitals were operating at or near capacity. Each drill took approximately one hour to complete, consisting of a roughly 20-minute hands-on exercise followed by a 20-minute hotwash. This brief intrusion was well received by the ED staff.

Communication and flexibility. Fire department company officers can immediately request a broad number of resources including law enforcement and logistical support. During most drills, company officers made hospital staff aware of the resources available to them if needed. In one memorable interaction, a LVFR captain asked the charge nurse at an early stage in the drill, “What resources will we need in 30 minutes?” It was clear by hospital staff feedback that this perspective was helpful, and the fire department’s chain of communication can be used to secure resources necessary to support hospitals. Surprisingly, many of the hospital ED staff members were unfamiliar with the capabilities of fire department personnel and equipment. The department’s ability to manage field triage at an MCI, intubate patients with compromised airways, and perform chest decompression were three of the biggest takeaways stated by ED staff.

Hospitals retain control. When operating on hospital property, federal laws may dictate several instances where hospital staff retain control of what is done. One of the initial challenges with policy development was the concern that fire department personnel operating on hospital property could create some liability for that facility. Are fire department/EMS personnel allowed to operate on hospital property where a “higher level of care” exists? This concern was eventually eliminated when a scenario was brought up that included a hospital being attacked. Given it is highly unlikely that a hospital could manage such an event without the support of fire department personnel, the groups participating in that discussion all agreed that this was not an issue.

One federal law that is always in play and not familiar to fire department personnel is the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA). EMTALA is a federal law requiring hospitals to provide a medical screening and stabilization to all patients as well as a physician-to-physician phone call prior to transporting a patient from one hospital to another. Meeting these concerns, an HAC SOP states that fire department personnel are not allowed to arrange for the transfer of a patient from one hospital to another without specific direction from the hospital staff.

Training Challenges

Making contact. Once a fire crew arrives at the hospital, it is imperative that the captain, now serving as the division supervisor, quickly locates the charge nurse. When this is done, both parties should stay together and function as a team, providing direction to those working on patients. Once in contact, the fire department officer and the charge nurse must maintain effective communication, which some found challenging during the training. Some hospitals had success using two-way handheld radios to communicate with clinical staff inside the ED and fire crews operating outside the facility.

Stepping back. Charge nurses must resist the temptation to treat patients and focus their attention on directing others involved in patient care and movement. In addition to directing personnel, they must leverage their knowledge of requesting supplies, equipment, and additional hospital staff to assist in the treatment and movement of patients. Once charge nurses were teamed up with fire captains and stepped back from task-level work, they quickly saw the benefit of doing so.

Participant Feedback

Feedback from all drill participants was collected verbally following each training event, in the form of a facilitated hotwash, and electronically, using an anonymous survey. Ninety-four percent (223 of 239) of participants in the electronic survey agreed or strongly agreed that fire department support would improve emergency department operations during an acute patient surge related to an MCI. Ninety-five percent (226 of 239) agreed or strongly agreed that the HAC concept was valid, and 88% (205 of 233) agreed or strongly agreed that they would feel comfortable initiating an HAC response.

Improving Supportive Response

Establishing HAC may improve information sharing and interaction with emergency management functions like family assistance centers, reunification efforts, and patient tracking. Having a fire department presence and respective chain of communications might allow for real-time snapshots of the challenges hospitals face.

The mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas, took place on May 24, 2022, during one of the final days of our exercises. This incident reminded us of the continued need to support hospitals during these crucial incidents. Hostile events have become less of a possibility and more of an eventuality for communities both large and small, rural and urban. Fire and EMS departments have a responsibility to plan for and train our personnel to respond in a coordinated manner to events like this. A department must establish trusting relationships with not only their fellow response agencies but also the local hospitals and other care providers to collectively meet the needs and challenges of these events. The SNFO HAC SOP is a positive outcome from one of southern Nevada’s most tragic moments, and it would not have been possible without the leadership of the Southern Nevada Health District, Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, and southern Nevada fire departments.

Author’s note: We want to acknowledge the responding law enforcement agencies, fire departments, private ambulance companies, hospitals, medical examiner’s office, emergency management teams, and county management for their work and professionalism on the night of October 1, 2017, and the months that followed. We also want to thank the many volunteers and donors from corporations and citizens.

GREG CASSELL retired from the Clark County (NV) Fire Department after 30 years of service, his last five years as chief. Prior to his 2015 appointment as chief, he served as a firefighter/paramedic, engineer, captain, and battalion chief. He has an extensive background in urban search and rescue and technical rescue operations and training for fire and EMS topics as well as a wide range of program development to include fire service integration with law enforcement. Cassell is a member of the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC), IAFC Western State Fire Chiefs Association, and IAFC Terrorism/Homeland Security Committee. He completed the IAFC’s Fire Service Executive Development Institute and has two associate degrees from the College of Southern Nevada and two bachelor’s degrees from Colorado State University.

JON WIERCINSKI began his fire service career with the Clark County (NV) Fire Department (CCFD) in January 1996. He then rose up through the CCFD suppression ranks, serving primarily in operational and training roles. Wiercinski responded to the October 1, 2017, Las Vegas strip shooting as an off-duty battalion chief, serving in a supportive role at the Multi-Agency Coordination Center. In March 2018, Wiercinski was promoted to CCFD deputy chief, assuming responsibilities for law enforcement coordination, homeland security, events planning, and fire investigation until his retirement in May 2020.

DAVID E. SLATTERY is a professor of emergency medicine and the director of emergency medicine research for the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV in Las Vegas, Nevada. He works clinically in the Emergency and Trauma Departments at the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada. From 2011 to 2022, Slattery served as the EMS medical director and deputy chief of the Medical Services Division for Las Vegas Fire & Rescue. Nationally, he serves as a board member on the National Oversight Committee for the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival Registry, a board member of the Council of Standards’ Emergency Communications Nurse System for the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch, and the prehospital section editor for The Journal of Emergency Medicine. Slattery also provides medical oversight for the Casino AED project. He researches optimizing resuscitation in the pre-EMS period of cardiac arrest, post-resuscitation care, emergency management of pulmonary embolisms, and emergency airway management.

KAREN DONNAHIE has been an emergency nurse for more than 30 years and actively involved in emergency management for 25, working in frontier clinics, Level 1 trauma centers, and many other places of emergency services. Donnahie serves as the clinical advisor to the Southern Nevada Healthcare Preparedness Coalition and is a regional transfer coordinator. She has a master’s of healthcare administration from Independence University and a bachelor of science in emergency medical services from the American College of Prehospital Medicine. Donnahie’s focus is on developing collaboration among health care facilities and prehospital providers to ensure the best possible outcomes for patients, responders, and communities.