On July 13, 2021, Suffolk (VA) Fire & Rescue (SFR) was presented with a high-rise fire in an occupied residential apartment building that challenged firefighters. At 0405 hours, Engine 1 and Ladder 3 were dispatched for a reported commercial fire alarm at 181 N. Main Street.

While the assignment for the alarm activation was being dispatched, the 911 center was receiving additional calls for a fire in the residential high-rise building with smoke reported on the fourth and fifth floors. Based on the number of fire alarm activations in the past as well as previous incidents throughout the years, the responding units thought the source of the smoke would be another “pot on the stove.”

- Battle-Ready Intelligence

- Fire Alarm Control Panel Systems and Firefighting Operations

- How to Control Sprinkler Flow in Mid- and High-Rise Buildings

- What Firefighters Need to Know About High-Rise Building Systems

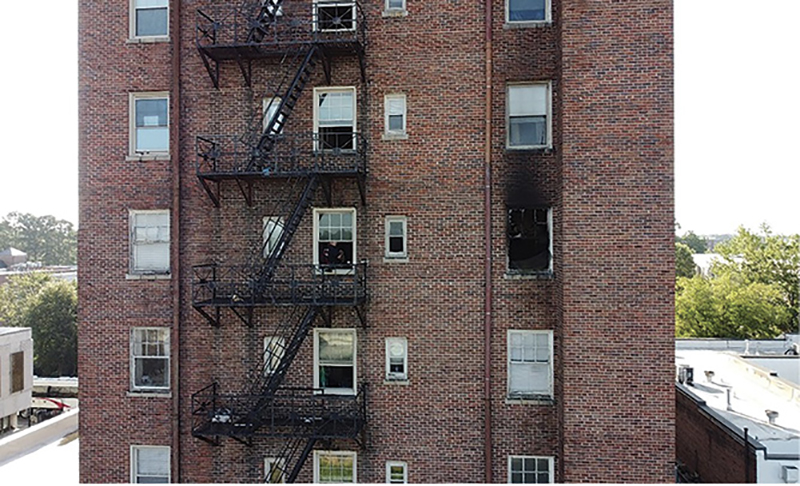

As the dispatcher upgraded the initial response to a commercial structural fire assignment, Engine 1 arrived on the scene at 0409 hours, reported smoke and flames showing from the exterior on the C side of the structure, and declared a “working fire” (photo 1). Battalion 1, hearing the size-up from the apparatus bay at Fire Station 1, requested a second alarm and an additional medic.

Preplanning and the Building’s History

Originally a hotel, the Suffolk Tower is an eight-story Type 1 fire-resistive residential high-rise apartment building with a basement constructed in the Colonial-Georgian Revival style on a two-story base. During preplanning, this building was thought to be “the one.” All SFR firefighters understood the probability and concern for a significant fire in this building. Many firefighters stated they “dreaded the day this building was on fire.”

The first-arriving officer recalled that when he was giving his size-up, he said, “This is a death trap.” The building was built between 1923 and 1925 and is nonsprinkled. The front of the building (A side) faces Main Street, with the lobby as the only entrance for residents or firefighters to enter or exit with a single, narrow interior stairwell. The B-side exposure is a storefront, and the C side is a parking lot with a fire escape on the building exterior that connects the ground floor to the eighth floor. The D side faces Market Street, with an entry door to a restaurant that occupies the first floor of the apartment building (with exception of the lobby). The building has two elevators—one for residents and one for freight. The building has many void spaces and open shafts because of remodeling over the years, and its current layout provides studio and one- and two-bedroom apartment homes.

The Suffolk Tower contained commercial spaces and the original hotel’s dining room and ballroom. At the time of the fire, the building had 59 apartments, 60 residents, and four businesses on the first floor (photo 2).

Operations

Immediately following Engine 1’s size-up, Battalion 1 arrived and established Suffolk Tower command. The command post was located on the A side in the parking lot on Main Street. The incident commander (IC) immediately noticed an occupant on the fifth floor of the A side signaling with a flashlight who needed to be rescued. Ladder 3 was directed to set up their aerial and rescue the occupant. Two occupants were removed by Ladder 3 from apartment 502 (photo 3).

Engine 1 was assigned fire attack, and Rescue 1 was assigned to locate the fire. Crews from Engine 1 and Rescue 1 met at the front door and took the interior stairwell to perform recon, execute rescues, and advise on fire conditions. Engine 1 proceeded up the stairs with tools and high-rise packs, while Rescue 1 went ahead of Engine 1 for recon. Rescue 1 confirmed heavy smoke and a working fire on the fifth floor. Engine 1’s crew went to the fifth floor and set up attack lines and connected to the fourth-floor standpipe (photo 4). Water supply was accomplished by Engine 1’s operator supplying the standpipe at the fire department connection on the D side. Engine 2 laid a supply line and supplied Engine 1. Ladder 6 was positioned on the C side to provide a “flying” standpipe as the secondary water supply for suppression operations if the standpipe was nonoperational or additional lines were needed from the aerial.

(1) On arrival, Engine 1 reported fire showing from the C side of an eight-story occupied residential apartment building. [Photos courtesy of Suffolk (VA) Fire & Rescue unless otherwise noted.]

(2) The Suffolk Tower is an eight-story Colonial-Georgian Revival-style brick building with a basement constructed on a two-story base. It was originally a hotel. (Photo by author.)

(3) Ladder 3, set up on the A side of the building, performs the rescue of an occupant from the fifth floor.

Evacuating occupants reported fire on the fifth floor. Rescue 1 confirmed the basement was all clear of smoke and fire and then climbed the stairwell, checking each floor as they ascended. While climbing the only stairwell, crews from Rescue 1 and Engine 1 passed approximately 15 occupants evacuating, and all occupants reported smoke on the upper floors. Crews checked the second through fourth floors and saw no smoke. Rescue 1 found dense black smoke and zero visibility on the fifth-floor landing. Rescue 1 donned face pieces and entered to perform a search and isolate of the fire while Engine 1 was stretching the hoseline to the fifth floor. With moderate heat and zero visibility, Rescue 1’s officer then used a thermal imaging camera and located one adult male fire victim laying supine in the common hallway (photo 5). Rescue 1 removed the fire victim to the protected fifth-floor stairwell. While executing the rescue, a Rescue 1 firefighter had his face piece removed by the now semicombative fire victim.

After turning over the fire victim in the stairwell, Rescue 1 searched the common hallway toward the C side and located the fire in apartment 518. The door to the apartment was opened slightly, with visible fire rolling overhead and entering the common hallway. Rescue 1 entered to perform a primary search and found heavy fire venting from two windows. Rescue 1 closed the door to protect the common hallway, while Engine 1 prepared the high-rise stretch to attack the fire.

When the attack line arrived, Rescue 1 opened the door to the fire apartment and Engine 1 performed fire attack (photos 6, 7). Rescue 1 then proceeded away from the fire room and forced entry into adjacent apartments to perform primary searches. Engine 4’s crew located an adult female victim in apartment 521 during primary searches. The second fire victim located by search crews was transferred to crews in the stairwell to be removed from the building. Rescue 1 completed primary and secondary searches on the fifth floor, finding no additional fire victims.

(4) From the high-rise pack and tools brought up the common stairwell, Engine 1 connected to the standpipe on the fourth floor and then attacked the fire on the fifth floor.

(5) The common hallway on the fifth floor showing the smoke and heat damage from the fire in room 518.

(6, 7) The fire room located in apartment 518.

Engines 2 and 3 were assigned to check the floors above the fire floor for occupants and fire extension. These companies reported a haze of smoke that extended to the eighth floor. Engine 3’s crew located an occupant on the seventh floor who could not exit the building because of smoke conditions and escorted the occupant to the fire escape and down to the sixth floor, where Ladder 6 lowered the occupant to the waiting medic unit, Medic 1, using the aerial platform (photos 8, 9).

Command requested a third alarm because of the number of victims located early on in the incident as well as the potential for more being found later. EMS 1 was assigned as the medical branch director, and command requested an additional tactical channel for the medical branch. The medical branch also coordinated fireground rehabilitation using medic crews and SFR’s rehab bus. Fire crews were then rotated through rehab. SFR’s mass-casualty bus, MCT 5, was requested by command but was not needed. Once the fire was under control, the fire floor was ventilated. Crews conducted additional searches on all floors, and no other occupants were located. Atmospheric monitoring was performed on all floors with all results within normal ranges. Crews assisted occupants with retrieving essential items in a systematic manner. Fire investigators obtained a confession from the occupant of the fire apartment who admitted to fire emergency personnel that he had set the fire. Fire Marshal 7 was assigned to Medic 3 to maintain custody of the patient while being transported to the hospital.

(8) Ladder 6 set up on the C side of the building to remove fire victims from the fire escape to awaiting medics by the tower ladder.

(9) The C side of the building showing the fifth floor, where the fire was venting from the window as well as the fire escape used by fire crews to rescue occupants.

Battalion 2 and Cars 1, 2, 3, and 4 assisted command with logistics, media relations, and relocating residents. Total responding units were 61 personnel on 14 suppression apparatus; seven advanced life support medics; and five command apparatus that performed five rescues. There were two civilian injuries and one firefighter injury.

Lessons Learned

Following were lessons the SFD learned from this incident.

- Prefire planning. Successful firefighting operations occur through preparation by understanding and training on the actual buildings in a department’s response area or community. Although buildings are constructed using similar techniques and classified by common building types, the effects of fire on each building depend on the individual building’s structural integrity, the fuel load contained within, and the voids that exist because of construction and settling. Firefighters are expected to understand the anatomy of buildings while being able to predict fire travel based on not only commonalities of building type but also on a prefire inspection of the unique features and circumstances each building presents—e.g., fire escape locations, suppression systems, retrofitted utilities, and repurposed rooms.

- Save lives by putting out the fire. Water on the fire is a top priority at a high-rise fire. As the fire progresses horizontally in common hallways, other occupants are now cut off from safely evacuating to a stairwell. In addition, vertical fire spread places occupants on floors above the fire in danger of being trapped by fire.

- Pressurize the stairwell early. With only one stairwell for fire operations and evacuation, charge the stairwell with a ventilation fan early in the operation to remove smoke that entered the stairwell because of fire operations for occupants sheltering or being rescued to the stairwell.

- Expansion of the incident command system. With a multialarm fire and multiple rescues, the IC’s span of control quickly becomes overwhelming. Early in the incident, the IC should assign command and general staff incident command positions to allow the additional responding resources to be assigned to the correct division, group, or section chief.

- Training. Performance is predictable based on planning, training, and understanding the elements of a building. Most high-rises have unique access points, escape routes, locations of systems and utilities, and rescue considerations that we must plan, practice, and anticipate. Take the time prior to the fire or incident to train by executing apparatus placement, hose stretches, evacuation procedures, and utility control.

- Deployment of resources based on the target hazard. Through critical task analyses, deploy the effective fire force that meets the critical tasks that must occur for unique or special-hazard buildings. In this case, an eight-story, nonprotected high-rise apartment building should receive an increased initial response over a standard commercial building fire. Through critical task analyses, tailor the initial response to specific address points so that the critical tasks can be performed by the initial responding alarm.

- Knowledge of building construction. National Fire Protection Association 220, Standard on Types of Building Construction, defines the standard types of building construction and is the foundation of a firefighter’s knowledge regarding building construction. This provides a firefighter with the basic understanding of building construction, which, in turn, provides for the understanding of the combustibility of structural and roof elements; the presence and location of fire walls, fire barriers, or partitions; and the location of shafts and voids in standard types of buildings. This basic understanding is then applied to the specific types of buildings in a firefighter’s community or response area during preincident planning and walk-throughs to review and anticipate how fire will travel based on the elements of construction.

MICHAEL J. BARAKEY, CFO, is a 29-year fire service veteran and the chief of Suffolk (VA) Fire & Rescue. He is also a hazmat specialist; an instructor III; a nationally registered paramedic; and a neonatal/pediatric critical care paramedic for the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia. Barakey is the participating agency representative and former task force leader for VA-TF2 US&R team and an exercise design/controller for Spec Rescue International. He has a master’s degree in public administration from Old Dominion University and graduated from the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program in 2009. Barakey authored Critical Decision Making: Point-To-Point Leadership in Fire and Emergency Services (Fire Engineering), regularly contributes to Fire Engineering, and is an FDIC International preconference and classroom instructor.