By CRAIG A. HAIGH and DENISE L. SMITH

Scenario: In a panic, the 30-plus-year veteran exited the training building and yelled, “Something is wrong with this air pack—it is not flowing air.” The firefighter was clearly agitated and mentally distressed. His face was flushed and streaked with sweat. With what appeared to be a terror-laden focus, he began to rip off his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and structural personal protective equipment.

- The Heart of a Firefighter

- Cardiovascular and Chemical Exposure Project

- Sudden Cardiovascular Death and Disability in Firefighters: A Complex Interplay

- Surviving the Fire Service Cardiac Epidemic

As a group of instructors worked to assist in removing his gear, the incident commander (IC)—i.e., the lead instructor—stopped the drill and pulled everyone outside. To say the least, he certainly had the attention of everyone watching the drill.

As the story began to unfold, the IC’s crew reported that they were advancing a charged 2½-inch hoseline toward the fire when “the lieutenant” began telling them to back out because his SCBA was not working correctly. In his excited state, it reportedly took a few seconds for his crew to comprehend what he was saying since the push down the hallway was going well and none of them were personally experiencing a problem. Adding to their surprise was the fact that each SCBA unit was brand new and had only been used a handful of times. Further, the crew indicated that their typically calm and unexcitable company officer had been in a state of near panic as he made a mad dash to get his people and himself out of the drill tower.

These reports were disconcertedly consistent with those of the live burn instructor (working as the interior safety) who was only a few feet away from the crew when the situation unfolded. Once out of his gear, the lieutenant began to calm and repeatedly reported that he was unable to get enough air from his SCBA. He said that the unit was somehow restricting the air flow and he felt like he was suffocating inside the mask.

He was clearly rattled, but he denied any medical complaints. He repeatedly said that he was now okay and simply needed to rest. He went to rehab, where an elevated blood pressure was noted, but paramedics attributed it to the stress of the event. He was allowed to sit out for the rest of the day’s drills, and when he headed home, he continued to say that he was feeling okay.

Because of the problem with his SCBA, the unit was immediately pulled from service and impounded. This included the lieutenant’s personally issued regulator and face piece. All the components were then sent to the manufacturer for testing. Based on the lieutenant’s reports, the focus of the incident revolved around the SCBA. Because of the lieutenant’s experience, all involved had no doubt that a mechanical failure had occurred, causing this battle-tested officer to have reacted this way.

Since the SCBA was the obvious culprit, word quickly passed within the department, causing several members to question whether they should trust these new units, regardless of how much the department paid for them. However, when testing was complete, all components met factory specifications based on National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1981, Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) for Emergency Services. Clearly, something had gone terribly wrong, but what?

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease encompasses all diseases of the heart and vascular system. The two most common types of cardiovascular disease—and the ones most related to sudden cardiac events following strenuous activity—are coronary heart disease and hypertensive heart disease.

Coronary heart disease. Also called coronary artery disease and atherosclerotic heart disease, this is caused by a buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances on the walls of arteries. High cholesterol, high lipids, high triglycerides, and an increased body mass index are common risk factors for the development of coronary heart disease. This buildup of atherosclerotic plaque in the arteries can partially obstruct blood flow, thus limiting the ability to increase blood flow to the heart muscle during periods of intense physical work, such as is seen in firefighting. In essence, the harder a firefighter works, the more oxygen needed by the muscles; therefore, an associated demand for blood flow is required.

As the heart increases in both rate and contractility (force), the narrowed and often stiffened vessels act like kinks in a hoseline. Kinks restrict the flow of water, which is generally considered a bad thing. If firefighters have been well trained, they have been taught to chase and remove kinks. Similarly, atherosclerosis restricts the flow of blood; it just can’t be fixed by “kicking the kink out” or straightening the line. The inability to increase blood flow during intense work, as described above, leads to a lack of oxygen, called ischemia. Ischemia increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

Atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries is a problem for another reason: If the plaque ruptures, which is more likely when pressure in the vessels increases, it can lead to a blood clot in the coronary artery that completely occludes blood flow, resulting in a heart attack (also called a myocardial infarction).

Hypertensive heart disease. This describes changes to the arteries and heart from hypertension. Hypertension is the medical term used to describe high blood pressure (>130/80 mmHg). Hypertension causes damage to the lining of the blood vessels, including the coronary arteries, and is a major contributor to coronary heart disease. Hypertension requires that the heart must pump harder with each beat and leads to cardiac remodeling. The increased heart size and thickness that results from hypertension is often referred to clinically as “end-organ damage,” and it greatly increases the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

Hypertension is often called the “silent killer,” reflecting the fact that it is very dangerous and that individuals often do not know they have it. In the early stages of disease progression, hypertension does not have perceptible symptoms. Nonetheless, even early stages of hypertension cause significant damage to the vessels and heart. Recognizing the damage done by hypertension and the risk it poses, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recently lowered the blood pressure values that defines a person as having hypertension.

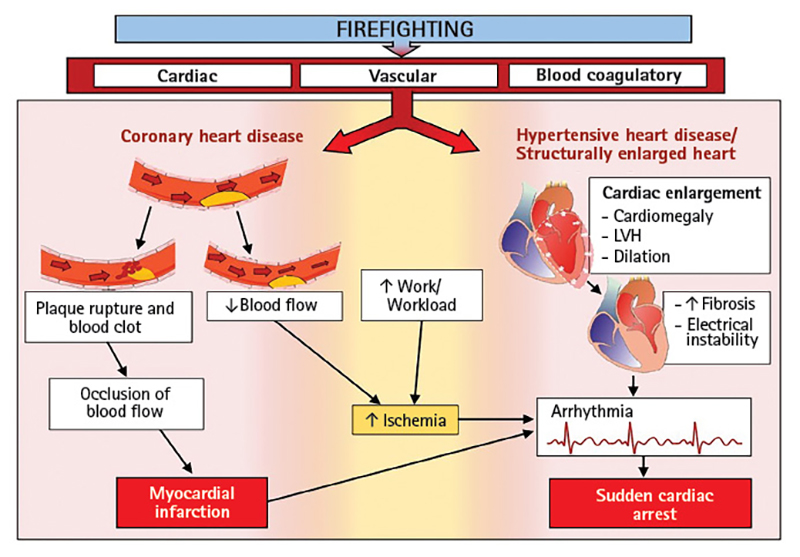

Figure 1. How Firefighters with Underlying Cardiovascular Disease Can Trigger a Cardiovascular Event

Firefighting can serve as a trigger for cardiovascular events in firefighters with coronary heart disease and/or hypertensive heart disease. Firefighting also causes several changes to the heart, vessels, and blood clotting. An individual with cardiovascular heart disease has atherosclerotic plaque that is vulnerable to rupture or may lead to ischemia because blood flow cannot increase to meet the demands of high workloads. Ischemia increases the risk of arrhythmias, and this risk is most pronounced in individuals with structural heart changes, often because of hypertension.

Figure courtesy of Skidmore College’s Better Heart Report: Building Evaluations That Translate Evidence & Research to Heart Evaluations and Related Training, First Responder Health and Safety Laboratory, Health and Human Physiological Sciences (2022).

Sudden Cardiac Events in the Fire Service

Over the past couple decades, sudden cardiac events have consistently accounted for approximately one-half of all line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) among firefighters. It is well-documented that firefighters are more likely to experience a sudden cardiac event while engaged in fire suppression duties (or shortly thereafter) compared to other tasks they might perform in the course of their work; this is because of the intense physical work of firefighting, heat stress, and the accompanying cardiac strain that can trigger a cardiovascular event in individuals with underlying cardiovascular disease.

A retrospective study looking at firefighter LODD autopsies from the past 20 years found that 80% of cardiac-related fatalities had both coronary heart disease and a structurally enlarged heart (reflective of hypertensive heart disease). Hypertension is a risk factor for coronary heart disease because it accelerates atherosclerosis and damages coronary arteries. Hypertension also leads to structural heart changes that increase the risk of sudden cardiac events. Thus, it is not surprising that researchers have found that uncontrolled hypertension is associated with a 12-fold increased risk of cardiac-related death in firefighters.

Figure 1 provides a schematic of how the strain of firefighting can trigger a cardiovascular event in firefighters with underlying cardiovascular disease. More importantly, most firefighters recover from the strain of firefighting. However, in individuals with coronary heart disease or hypertensive heart disease, the strain of firefighting can trigger a heart attack or a sudden cardiac risk.

Research Study

Given the critical role of hypertension in advancing cardiovascular disease (both coronary heart disease and hypertensive heart disease) and increasing the risk for sudden cardiac events, researchers recently examined blood pressure values and antihypertensive medication usage by decade of life for firefighters and compared these numbers against the general population. This study was conducted by researchers working in collaboration with occupational health care providers and a cardiologist who is a former firefighter/paramedic. The study evaluated a geographically diverse cohort of medical records from occupational health clinics based in southern Arizona, northern Virginia, central Florida, and the capital region of Indiana that serve firefighters and included records from 5,063 male firefighters and 274 female firefighters. For comparative general population numbers, the study used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, which included 3,004 males and 3,322 females.

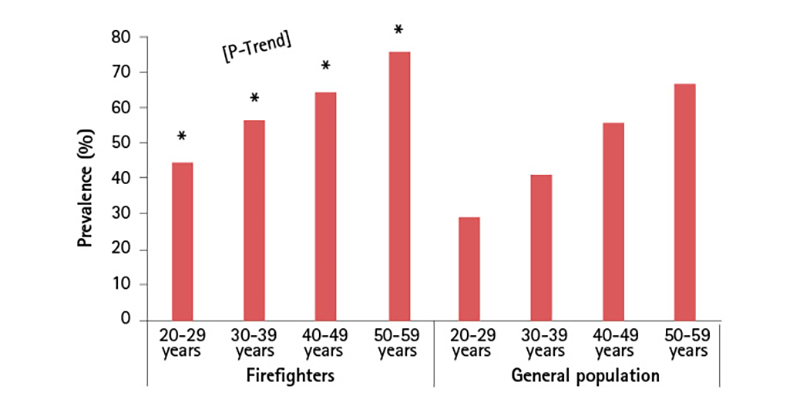

As summarized in Figure 2, the study found that a shocking 69% of firefighters had evidence of hypertension. The prevalence of hypertension increased with age, specifically, among male firefighters: 45% of firefighters between the ages of 20 and 29 were hypertensive, and 77% of firefighters between the ages 50 and 59 had hypertension. Furthermore, firefighters had a higher prevalence of hypertension than the general population for each age group that was studied.

The study also found that female firefighters had higher levels of hypertension than the general population among those who were more than 50 years old and that many firefighters were unmedicated or their hypertension was uncontrolled.

Figure 2. Hypertension in Male Firefighters Compared to the General Population (by Decade)

Figure courtesy of Khaja SU, KC Mathias, ED Bode, et. al. (2021).

It is unclear why firefighters have a higher prevalence of hypertension than the general population. The researchers noted that more firefighters had elevated diastolic blood pressure values than systolic values. Perhaps the elevated blood pressure values reflect a state of increased vigilance or higher levels of occupational stress among firefighters. Regardless of the reasons for the elevated blood pressure, it was clear that hypertension presents a major threat to the fire service and is known to cause the advancement of coronary heart disease, leading to structural heart changes including increased wall thickness and weight. Both of these conditions increase the risk of sudden cardiac events.

Interestingly, a 2012 study investigating the prevalence of hypertension in the U.S. workforce found that protective service workers (police and firefighters) had the lowest awareness of their hypertensive blood pressures, the lowest treatment of hypertension in those who were aware of the condition, and the lowest prevalence of controlled blood pressure.

The Rest of the Story

Looking back to the case study described at the beginning of this article, the longtime fire officer was found to have extensive unreported cardiovascular disease. The officer had undergone annual NFPA 1582, Standard on Comprehensive Occupational Medical Program for Fire Departments, medical exams, and it was reported to the fire department that he was fit for duty. Soon after the incident, however, the officer elected to retire and within months was forced to undergo cardiac bypass surgery because of extensive coronary heart disease that resulted in blockage in multiple coronary arteries. Long-term uncontrolled hypertension likely contributed significantly to the coronary heart disease progression.

Based on this postretirement health emergency, coupled with the fact that the SCBA was working appropriately, it can be surmised that, as the lieutenant’s heart rate became elevated to address the increased oxygen demand of the working muscles, myocardium, and brain, he was simply unable to supply the demand because of the underlying disease process. In retrospect, all involved feel fortunate that the lieutenant identified a problem (even though it wasn’t the SCBA) and competently evacuated his personnel from the immediately dangerous to life or health atmosphere. By all accounts, if he would have allowed the crew to continue the training evolution and ignored his own physical impairment, this near-miss incident could have easily ended in a sudden cardiac event.

Final Word

The good news about many of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including hypertension, is they can be modified by lifestyle choices. Changes in diet, exercise, weight loss, getting quality sleep, and managing stress levels can all impact an individual’s risk of cardiovascular disease and suffering a sudden cardiac event. For example, exercise training is effective in lowering blood pressure by approximately 4-8 mmHg.

In some cases, prescribed medication is necessary to combat the disease process. When lifestyle changes are not sufficient to control blood pressure, medications should be used. When blood pressure remains uncontrolled, it continues to silently cause damage to the heart and blood vessels throughout the body. Physicians who treat firefighters should aggressively counsel their patients on the best ways to manage their blood pressure.

As researchers, we like the words written on the gymnasium wall at the Illinois State Police Academy: “If you choose law enforcement, you lose the right to be unfit.” The important message is that these words apply equally to the fire service and give us good reason to take a lesson from our brothers and sisters in blue. Being fit for duty includes not only physical training but also annual medical evaluations, using feedback from medical evaluations to help control disease processes, managing our stress, and getting the right amount of sleep.

The job we do is hard, and we need to never forget that those we serve are counting on us. Therefore, make sure that you do all that is possible to be ready to meet their needs when they call.

References

Brook RD and S Rajagopalan. (2009). Particulate matter, air pollution and blood pressure. American Society of Hypertension (3), 332-350.

Davila EP, EV Kuklina, AL Valderrama, et al. (2012). Prevalence, management, and control of hypertension among US workers: Does occupation matter? Occupational Environmental Medicine (54), 1150-1156.

Di Palo KE and NJ Barone. (2020). Hypertension and heart failure: Prevention, targets, and treatment. Heart Failure Clinics, 16, 99-106.

Emdin CA, A Kiran, SG Anderson, et al. (2016). Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 387, 957-967.

Fahy RF, JT Petrillo, and JL Molis. (2019). Firefighter Fatalities in the US. National Fire Protection Association, 7.

Fogoros RN. (2022, April 22). The Significance of Cardiac Remodeling. Very well health. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-cardiac-remodeling-1746198.

Kales SN, ES Soteriades, and CA Christophi. (2007). Emergency duties and deaths from heart disease among firefighters in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356, 1207-1215.

Khaja SU, KC Mathias, ED Bode, et. al. (2021). Hypertension in the United States Fire Service. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18. Retrieved from http://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph.

Lee CJ, J Noh, DS Hyun, et. al. (2020). Blood pressure and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among firefighters. Journal of Hypertension and Management, 38, 850-857.

Liu MY, N Li, WA Lie, et. al. (2017). Association between psychosocial stress and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurological Research, 39, 573-580.

Medic G, M Wille, and ME Hemels. (2017). Short and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and Science of Sleep, 9, 151-161.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: NHANES Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov.nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx.

Smith DL, E Bode, BS Hollerback, et. al. (2022). Better Heart: Building evaluations that translate evidence and research to heart evaluations and related training. Saratoga Springs, NY: First Responder Health and Safety Laboratory, Skidmore College.

Smith DL, JM Haller, M Korre, et. al. (2018). Pathoanatomic findings associated with duty-related cardiac death in US firefighters: a case-control study. Journal of the American Heart Association.

Stokholm ZA, JP Bonde, KL Christensen, et. al. (2013). Occupational noise exposure and the risk of hypertension. Epidemiology (24), 135-142.

Tobia M, SA Jahnke, TJ LeDuc, et. al. (2020). Occupational Medical Evaluations in the US Fire Service: State of the Art Review. International Fire Service Journal of Leadership & Management, 14, 17-26.

Yang BY, Z Qian, SW Howard, et. al. (2018). Global association between ambient air pollution and blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution, 235, 576-588.

CRAIG A. HAIGH is a retired fire chief and the author of The Dynamic Fire Chief: Principles for Organizational Management. He began his fire service career in 1983 as a volunteer firefighter in Hampton, Illinois, and served more than 30 years as a chief for departments in Illinois and North Carolina. Haigh has also served as an interim village manager. He was named the 2012 Illinois Career Fire Chief of the Year and received the 2019 International Association of Fire Chiefs Chief Alan Brunacini Executive Safety Award. Haigh has published articles on a variety of leadership topics in more than 50 trade journals. He retired in July 2021 and serves as an independent consultant focused on management and organizational leadership as well as firefighter health and safety. Haigh is the spokesperson for the congressionally mandated National Firefighter Registry and is a regular speaker and presenter, sharing his experiences and insights with emergency service and private sector leaders.

DENISE L. SMITH is a professor of health and human physiological sciences and director of the First Responder Health and Safety Laboratory at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. She is also a senior research scientist at the University of Illinois Fire Service Institute. Smith is the author of Exercise Physiology for Health, Fitness, and Performance. She has also published more than 100 scientific peer-reviewed articles and been awarded more than $14 million in research funding from FEMA-AFG, DHS S&T, NIOSH, and DoD. Smith received the Dr. John Granito Award for Excellence in Fire Service Leadership and Management Research, is a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine, serves on the National Fire Protection Association Fire Service Occupational Safety and Health Committee, is on the Advisory Board of the Underwriters Laboratories Firefighter Safety Research Institute, and has conducted more than 40 fatality investigations for NIOSH. She earned her Ph.D. in kinesiology with a specialization in exercise physiology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.