WHAT WE LEARNED ❘ By MARCEL J. BERUBE

Miami-Dade County, Florida, is one of the busiest ports of trade in the world. Shipments of products and equipment arriving by truck, rail, and ship are transferred by freight forwarders for shipping overseas and in North America. Many of the products are toxic, flammable, and water reactive. When materials are transferred from one intermodal (shipping) container to another, there is the possibility that the container can being dropped or punctured by a forklift and that incompatible products such as fuels and oxidizers can be shipped in the same container.

- Video: Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Crews Respond to Ammonia Leak

- The Gray Area: Firefighter Rescue and Hazmat

- Teaching Hazmat in a Pandemic-Driven World

Level 3 Hazmat Response

On June 20, 2022, a highly toxic and corrosive material being off-loaded from a refrigerated semitrailer at a freight forwarder was discovered to be escaping from its cylinder. This leak would ultimately require a full Level 3 hazmat response from Miami-Dade Fire Rescue (MDFR). The escaping product was identified as anhydrous hydrogen fluoride (HF). The product was formulated in the United States and destined for shipment overseas. When in an intact, undamaged pressurized cylinder, HF remains a liquid with a boiling point of 67°F. Consequently, the rate at which the product escapes from a leaking cylinder increases as the ambient temperature rises. Accordingly, with the temperature approaching 90°F, hazmat technicians had to contend with an ever-increasing amount of product escaping and the toxic threat becoming more serious. When anhydrous HF is dissolved in a solution with water, it becomes aqueous HF solution, also known as hydrofluoric acid.

The product was shipped from Oklahoma and spent four days on the road before reaching Miami. Once it arrived at the freight forwarder, the truck driver cut the seal that the shipper in Oklahoma placed on the doors of the semitrailer and opened them so a forklift could proceed to empty the entire load. While off-loading the shipment, the forklift operator discovered that one of the HF cylinders was damaged and leaking, and he notified the truck driver. The truck driver examined the shipping papers that indicated that the product leaking was toxic and corrosive, and he called 911. The call was received at 1:30 p.m., and the MDFR alarm office dispatched an “explosive alert” consisting of a commercial building fire assignment including a hazmat company and two hazmat support engine companies.

The first–arriving company, Engine 48, followed department procedures and, accordingly, began evacuating the warehouse, denying entry, and establishing a hot zone with a 300-foot barrier away from the building. The truck driver, who complained of a strange sensation in his mouth, and the forklift operator, who had no complaints, were evaluated on scene by Rescue 28’s hazmat medic and were persuaded to be transported to a hospital for further evaluation and possible treatment for exposure. Rescue 28’s medic crew were certified hazmat technicians with specialized training in treating victims of exposure to hazardous materials. Additionally, they support and evaluate personnel operating in a hot zone.

There may be questions as to why the two patients—one with a minor complaint and the other with no complaint—would be persuaded to go to the hospital. This is a very important lesson learned and reinforced: Exposure to corrosives can have delayed effects, depending on several factors, including the product’s water solubility with the moisture in the lungs and respiratory tract. The same can be said about inhaling the products of combustion of petrochemical-based fuels.

On arrival, hazmat companies established hot, warm, and cold zones and a research branch. One of the first steps after identifying a product is to determine its properties and hazard, containment, and mitigation procedures. At a hazmat incident, research branch members operate in a walk-in section of MDFR’s hazmat branch that serves a reference library equipped with manuals, television screens, and computer and weather analysis equipment. From reference materials, the research branch determined the exposure routes for HF to be inhalation, skin, and eye absorption. The material is highly irritating to the eyes, skin, nose, and throat. HF targets the eyes, skin, bones, and respiratory system, resulting in pulmonary edema and chemical burns. Reference material recommends that personnel working in a possible HF leak be protected in fully encapsulated clothing and self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA).

The hazmat branch then devised a plan for a reconnaissance operation: Personnel in fully encapsulated Level A suits and SCBA would enter the warehouse to examine the offending cylinder and determine the extent of the leak. Additionally, the reconnaissance team would attempt to determine if the leaking cylinder could be capped by improvising an Emergency A-Kit, which is designed for use with the standard DOT 3A480 and 3AA480 100- and 150-pound capacity cylinders of chlorine, respectively. Kit “A” consists of devices and tools to contain leaks in and around the cylinder valve and in the side wall of chlorine cylinders (photo 1).

(1) Hazmat technicians in fully encapsulated Level A suits practice attaching an A-Kit bonnet to a chlorine cylinder during a training exercise. (Photo by Eric Goodman.)

While the entry team was donning their protective equipment, a Level 2 technical decontamination operation was being established for the entry team when they withdrew from the hot zone (photo 2). The entry team fastened litmus- and fluorine-detecting paper to a long pike pole to ascertain its pH as well as the presence of fluorine while keeping their distance from the cylinders. The reconnaissance team then withdrew and reported that they did not get any positive indications from the litmus or fluorine paper. The team also noted that the damaged cylinder was blocked from view by other cylinders and needed to be isolated before it could be examined and determined if fastening an A-Kit could be a viable option.

(2) Decon team members wearing Level B suits and self-contained breathing apparatus assist personnel in Level A suits after they withdrew from the hot zone. [Photos 2-8 courtesy of Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue.]

Drone Operations

Since the reconnaissance team could not determine the cylinder’s location and condition, the hazmat branch requested MDFR’s Drone Unit through command in the hopes that the drone could be flown into the warehouse and get a bird’s-eye view of the top of the HF cylinders.

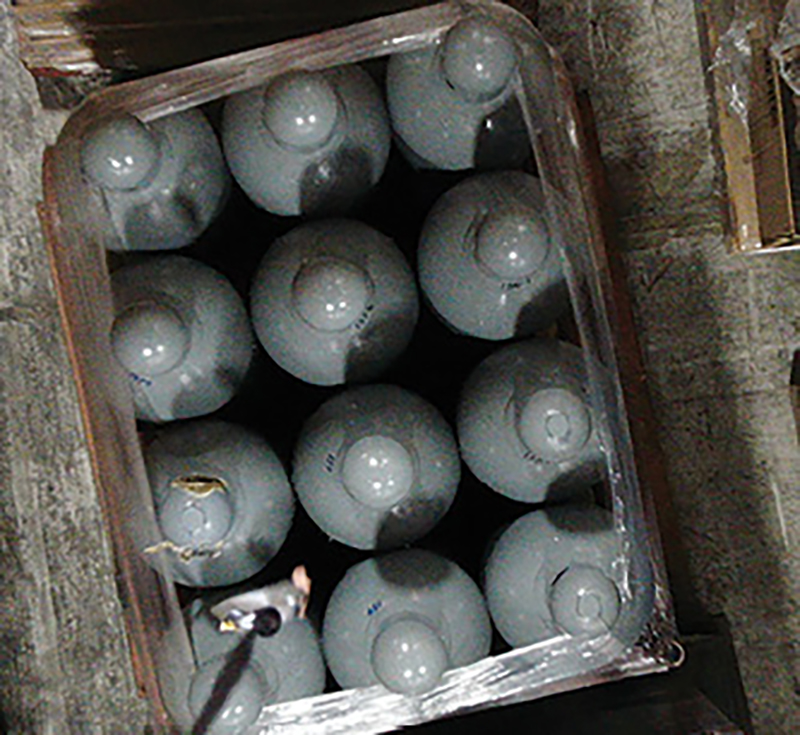

On arrival, the drone unit worked with hazmat technicians to rig the drone with pH and fluorine paper (photo 3). The drone then flew into the warehouse, where its video camera gave the hazmat branch a clearer picture of how to isolate the cylinder (photo 4). Furthermore, the drone was able to take a sample with the papers from directly above the damaged cylinder (photo 5) and check for residual spilled product in the semitrailer (photo 6). The analyzing papers did not change color, indicating that the cylinder may no longer be leaking. This was a factor in the decision-making process to allow another entry team to operate in Level B suits so they could operate a forklift to move cylinders and other containers that were blocking access to the damaged cylinder (photo 7).

(3) A hazmat technician rigs litmus- and fluorine-detection paper to a drone.

(4) A drone operator at the controls while watching live video feed.

(5) A drone rigged with detection papers flies into the semitrailer to check for any residual product.

(6) A drone video view at the top of the cylinders, which are palletized and shrink-wrapped in clear plastic sheeting. The drone dangles detection papers over the top of the cylinders to determine pH and the presence of fluorine. Corrosive action of the hydrogen fluoride has partially eaten through the protective cap of the leaking cylinder.

(7) Personnel in Level B suits prepare to make entry to isolate the offending cylinder.

The second team was able to isolate the damaged cylinder and move it toward a front overhead door opening. The second entry team’s entire operation was monitored by the drone team and entry officer as a safety precaution. This broadcasted live feed to command so if anything went wrong the rapid intervention team could be activated and rescue any distressed team members. A third entry team was also outfitted in Level A suits to attempt to improvise the A-Kit. Once more, the drone was deployed for live monitoring of the entry team, which was able to place an A-Kit bonnet over the valve assembly on the damaged cylinder without incident (photo 8).

(8) A leaking hydrogen fluoride cylinder is effectively contained by improvising a chlorine A-Kit bonnet.

The following day, representatives from the product’s manufacturer weighed the cylinder and compared its weight to the quantity listed on the shipping papers. According to their calculations, only two pounds of HF had escaped, and that 87 pounds of the product remained in the cylinder secured by the A-Kit bonnet.

One of the lessons learned from this incident is to never assume all the product leaking from a damaged container will escape before hazmat personnel intervene. Accordingly, personnel should continue operating as if the cylinder still contains product. Additionally, it was learned that MDFR’s overpacked container, used to transport a 150-pound ammonia tank, would be too small to contain the HF container.

A Resource-Intensive Operation

A Level 3 hazmat response requires a concerted effort of many resources, including incident command, product identification, research into properties and mitigation, decontamination, and isolation of the area. Additionally, operating in Level A suits in the heat of a South Florida summer is extremely punishing on personnel, requiring rehabilitation and rotation of personnel.

Determining the presence of hazardous materials is paramount. Fortunately, the semitrailer was properly placarded, and the driver had the shipping papers. Unfortunately, the warehouse had no diamond signs for National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 704, Standard System for the Identification of the Hazards of Materials for Emergency Response, to indicate that hazardous materials were handled. As a result, one of MDFR’s battalion chiefs requested a fire inspector’s response, who issued a notice of violation for failure to comply with NFPA 704. Finally, the drone application for hazmat should be incorporated on an initial entry for reconnaissance and monitoring of entry teams in the hot zone. This will give an overall view of the situation as well as supply any initial readings within the hot zone.

All MDFR personnel receive International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) Hazmat First Responder Operations (FRO) training. First-arriving companies are trained to operate for five to 10 minutes before a hazmat company’s arrival. Moreover, IAFF’s FRO classes teach firefighters to obtain shipping papers and safety data sheets, if conditions permit, and to recognize and identify clues that could indicate the presence of hazardous substances and weapons of mass destruction. This will allow the first-arriving units to isolate and deny entry and provide information that will be vital to developing an incident action plan.

MARCEL J. BERUBE has been a firefighter/paramedic for Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue (MDFR) for 19 years. He has also worked as a MDFR hazmat tech for 13 years and a hazmat specialist for three years. Berube is the lieutenant in charge of logistics, training, and research and development for the MDFR’s Hazmat Bureau.