BY RYAN PETSCHE

Firefighter safety is A subject that is never overlooked but is often understudied. This year is already tragic: As of April 18, 2022, there are already five line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) that occurred during structure fire operations. An LODD is the worst-case scenario for any fire scene. It’s a heartwrenching event that shatters the company; the fire department; the community; and, most importantly, the family.

This article will go over the SLICERS operations acronym and how you can use it to ensure life safety for every firefighter at your scene is the number-one priority. Firefighters use the memory aid SLICERS to assist them in their fireground operations. It stands for the following: Size-up, Location of the fire, Identify and control the flow path, Cool from a safe location, Extinguishment of the fire, Rescue, and Salvage. The last two are the most important for our community and are not necessarily in sequential order as the first five must be. Rescue and salvage are matters of opportunity; at times, they will significantly outweigh other options during your incident.

- Rethinking RECEO VS: Breaking Up with an Old Friend

- Firefighting Tactics: SLICERS and DICERS

- ISFSI: Principles of Modern Fire Attack Video

- Safety First vs. High Performance: What Is Too Safe?

Size-Up

A very important part of successfully managing a fire scene comes from a good initial scene size-up. This information determines “Go” or “No-Go” for rescues, the method of attack, the additional resources required, and all other fireground operation factors related to fireground operations. Scene size-up is constant on the fireground; all members should participate and report changes in conditions to the incident commander (IC) or their designated officer. A good size-up should notify all incoming units of what has happened, is happening, and is going to happen. Give a good on-scene report and, following a 360° survey (if possible), announce the tactics and strategy.

Dispatch: “Typical Fire Department, you are needed at 101 Main Street for a structure fire with an occupant in apartment 4.”

Initial size-up report: “Dispatch, Command 1 is on scene and will establish 101 Main Command. We have what appears to be a two-story quadplex apartment with lightweight construction. Moderate fire is coming from a window on the first floor of the A/D corner with smoke coming from the eaves and the ridge. I’ll be out to investigate. Your hydrant is on Main and First Street.”

Post-360° report: “All incoming units, apartment 4’s entrance is on the second floor, Delta half; the entrance is on the Charlie side. Bystanders have stated the apartment is occupied by an elderly woman who is unable to leave. First-arriving engine, you are to VEIS [vent-enter-isolate-search] through the Charlie-side door. Next arriving, you are to begin a transitional attack on the A/D corner. We need to knock down these flames. I have turned off the gas. Dispatch, please notify utilities to respond.”

This initial scene size-up tells crews that we have a two-story quadplex with a building construction type that does not fare well in the fire conditions that are being reported. This creates a sense of urgency should a rescue be needed. After a 360 and potentially gathering information from a bystander, the IC then relays there is a rescue to be made and that it will be the number-one priority. The IC tells how to access the apartment and notifies the first two crews of their assignments. It’s important to note that during your 360, you should be completing the next two sequential steps: location of the fire and identifying the flow path.

Planning for Successful Size-Up

I understand all departments operate differently, and some consider this too much radio traffic. It’s up to your department to decide whether an initial size-up and a 360 report are necessary. In this scenario, it is prudent to rapidly relay that a rescue is needed and the best access to that apartment, but all other information may be delivered face-to-face or however your individual department may handle communication.

What should dictate your initial tactics is deciding if you have a searchable and survivable area for this victim. There is often a surprising amount of searchable space, even when heavy fire is showing. Underwriters Laboratories (UL) studies on searchable space have shown that it is the duration of exposure that proves more fatal than the amount of heat. I highly recommend viewing the linked study; it may surprise you just how much space is survivable in a structure. Proximity to the fire room and elevation relative to the fire most closely relate to survivability. We must use research and experience to determine if a space is searchable. Consider also the building’s construction and the length of time it has been exposed to heavy fire. Without a doubt, the most difficult part of our job is recognizing when our efforts would be futile or when the building is at risk of collapse. In the wise words of one of the most influential chiefs to ever shape the fire service, the late Chief Alan Brunacini, from the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department, said, “Risk a lot to save a lot, risk a little to save a little, risk nothing for what is already lost.”

In this size-up, we have recognized that there is a searchable area above the fire. We’ve determined that the space has a confirmed occupant who is unable to leave the building on her own. Seconds count in this situation. Searching above a fire room in lightweight construction is not ideal, especially without water already flowing beneath you. This is a prime example of risking a lot to save a lot. This decision is influenced by the amount of fire below apartment 4, the time in which units will arrive, and the fact that there is smoke coming from the ridge and eaves. This signifies that smoke is traveling through the building and has most likely entered the trapped victim’s apartment. A smoke-filled area is searchable and even in the presence of heat will be largely survivable. However, three minutes without oxygen can begin to cause brain damage, so a rapid search and rescue is needed to ensure a successful rescue.

Fire Location

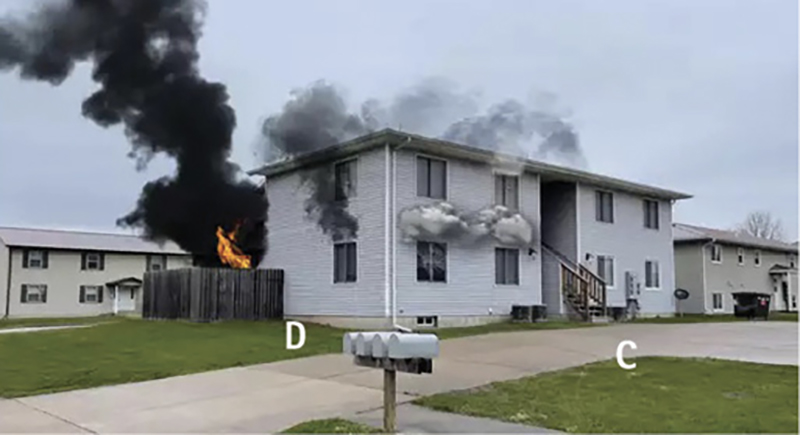

As a part of your on-scene report after your 360, you should have a good idea of where your fire is. This sets the tempo for the rest of your call. In determining the fire location, you should look for visible flames, read the smoke, look at the building’s construction, listen to your bystanders, and be familiar with the layouts of structures in your community. In our scenario, we have moderate fire showing at the A/D corner of the first floor. This implies we have a fire most likely in the growth stage that has taken out a window. Lack of heavy flames shooting out every wall/window of a space implies it is not a fully developed fire, but it is rapidly becoming one. An otherwise unremarkable 360 was given; however, smoke has been noted coming through the eaves and ridges (photos 1-2).

(1-2) Photos by author.

Reading smoke is a skill all commanders, officers, and firefighters should be intimately familiar with. Its speed, density, and color should all be considered in determining the fire’s spread. Listless or lazy light gray smoke from a ridge or eave should imply that the structure is filling with smoke. A fast plume of dark gray to black smoke means that either conditions inside are rapidly worsening or fire has spread to the attic/upper floors. In our scenario, the smoke that is not near the fire room is light gray, which indicates that smoke is traveling through the structure from the first floor. So, it is likely that the room above the fire has excellent conditions for a search and increased odds of victim survivability. If our scenario had pressurized black smoke coming from the attic, you would reconsider sending a crew in for VEIS since fire is likely below and above them. At the end of this article, several Fire Engineering articles are referenced that are invaluable for explaining the process and art of reading smoke.

In addition to knowing the fire load and reading smoke, you must identify the building construction. Balloon-frame construction, common from the mid 1800s to the early 1950s, poses a unique challenge to managing a fire in the basement or on the first floor of a multistory building. These houses have continuous wall void spaces running from the basement to the attic. A fire in the basement can rapidly spread through the walls to the attic in addition to spreading to the intervening floors. Identifying balloon-frame houses can be difficult, but the age of the structure and certain clues can tip you off. A house with old asphalt siding should be a red flag of an older house, but keep in mind new modern siding can hide balloon framing underneath. Interior crews can identify balloon framing from within when encountering void spaces in the wall. Lath-and-plaster walls are also an identifier, since that was only used until the 1950s. Even windows vertically lined up in the same stud space should draw your attention when assessing older homes. See references for additional resources for exploring balloon-frame houses and their problems.

Beyond seeing fire with your own eyes, listen to the homeowners. Don’t just shoo every civilian away from the fire scene; ask any bystanders about any fire that is not immediately visible. Someone called this fire in; that person could be invaluable in locating a concealed fire within the occupancy. Bystanders’ accounts of what happened, combined with a working knowledge of your community’s building layouts, should give you a good idea of where the fire may be. Using your 360 will help you understand the layout. However, be wary of trusting all bystanders; some may be overeager to help and give incomplete information, while in rare cases it could be downright malicious. Window size, placement, plumbing vent pipes, and other visuals can give you building layout clues without your ever going inside. The ability to size up the home’s layout without ever stepping inside is an invaluable skill to learn and practice. See references for additional reading.

Identifying and Controlling the Flow Path

To understand the flow path, we must recognize the building construction in conjunction with the location of the fire. Before the early 1940s, few homes had insulation as we know it today; most used ineffective insulation or none at all. Some old homes still have drafts throughout the house. Fast-forward to modern-day homes, and you may notice that some inside doors shudder or pop open when a different exterior door to the residence is slammed. The combination of effective insulation and sealing in the exterior walls/foundation has created an almost airtight environment in the modern building.

Knowing that the building you will be assessing is essentially airtight is especially important when identifying the flow path. If you open a window to a residence, that is now the only large opening for that airtight structure. If you open a second window on the other side of the building, you now have created a flow path from one window to the other.

Apply these concepts when fire is venting out a window as in this scenario. Through your 360, you know that all doors to the residence are shut and that the fire in the A/D corner has a window to provide air. The open window and the oxygen it provides will draw fire to it. If the fire’s room of origin has an open door to the rest of the structure, you then must worry about creating more openings and thus a flow path. Understand that although fire prefers to go up, that does not mean it will not spread any which way it can.

Many LODDs have been traced back to a firefighter being in the fire’s flow path. All too often, a door is left open, creating a flow path from the fire to that door. Advancing crews may not realize that they are not only attempting to extinguish the fire but also fighting a fire that is rapidly advancing toward them. A good suppression crew habit would be to leave one firefighter by the door through which they entered and keep it two/thirds shut prior to introducing water onto the fire.

As part of our 360, we will acknowledge that any opening to this building will create a flow path for the fire to spread throughout the house. Crews entering through a doorway will be fighting the fire directly in the flow path of the fire’s spread. There are many strategies to combat this effect through tactical ventilation. Knowing we have a fire that is most likely isolated to one apartment, it would be feasible to knock down as much fire as possible from the outside and then enter that apartment with a positive pressure ventilation fan behind you to create a flow path away from your crew and out the open window the fire has created. Alternatively, this first-floor apartment could have a second window opened to create horizontal ventilation through an alternative route than the way the engine company is advancing. Note that any ventilation should be coordinated with a rapid attack on the fire. Ventilation is never a standalone procedure except in emergency situations such as a VEIS; even then, it is important to limit and control that flow path away from yourself and your victim. More information on flow paths can be found in the references below.

Cool from a Safe Location

What’s next involves without question the most coveted job on the fireground, fire suppression. Fire suppression means fighting fire with water and reducing it to a controllable amount of fire. This is the “meat and potatoes” of managing any structure fire. Tactics and strategy dictate how this happens, but how it should always occur is to cool from a safe location. All read this phrase the same way, but many disagree about what is a safe location. It may be inside the structure fighting your way to the fire through the hallway or hitting it from the outside. The age-old debate of “pushing fire” when you launch an exterior attack has been thoroughly researched. Studies conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and UL have shown that the rapid cooling action on the fire is very beneficial. Air entrainment will push fire/steam but not significantly, usually raising surrounding rooms’ temperatures by only a few degrees before the temperature declines. Flow path dictates where fire goes more so than air entrainment.

In our scenario, fire is visible from the exterior and a crew will go to the floor above it. A typical transitional attack involves using a straight stream to apply water to the ceiling of the involved room for 10 to 15 seconds. Using a straight stream allows the fire by-products to still exit through the window. A straight stream held steady and aimed at the ceiling for 10 seconds will effectively reset the fire and not disturb the thermal layering. An exterior attack in this manner should not significantly push fire and will immediately help conditions. If you were to attempt an exterior attack with a wide fog stream covering most or all of the window, it would cause a small push and can disrupt the thermal layering. In that case, you would trap the superheated gases and use air entrainment to potentially move the superheated gas elsewhere. In the NIST and UL studies, days were spent attempting to push fire; at most, they could temporarily raise the temperature by a degree or two before the temperature throughout the structure rapidly dropped. A straight stream aimed at the ceiling will not worsen conditions inside the fire room or surrounding rooms.

A UL study on cooling from a safe location was performed as a part of a water mapping study. UL found that the hoseline is as effective as your line of sight—that is, unless you can see the fire, you often won’t be effective with your attempt. It found that when it comes to cooling a room, the higher your angle when aiming at a ceiling, the more effectively you cool the environment. A classic “wall-ceiling-wall” method would be ideal in a hallway since it keeps most of the water heading in front of you as you head toward the fire room. A smooth bore nozzle is the most effective tool for this because of the least amount of air entrainment.

A large factor in air entrainment is the stream’s reach. The more the stream breaks, the more air entrainment occurs. Therefore, the closer you get and the higher your angle, the more effective you will be at cooling the room. You can use this method from inside or outside the structure.

Achieving a quick reset on the fire from the exterior expands your “safe location” by a large margin. You now are able to enter the structure and attempt an interior attack with much improved conditions. Controlling the air flow through tactical ventilation, you can now aggressively attack the fire since your safe location now extends closer to the seat of the fire. In addition, you have now made the apartment above safer for your search crew, as the fire will have less heat and less opportunity to spread to their floor.

All too often, I see videos of firefighters entering a structure into a living room while flames shoot out the window next to them. This may make for a cool picture, but it involves unnecessary risk. When debating on an aggressive interior or a defensive strategy, the answer always lies in one simple phrase I enjoy repeating: “If you see fire, put water on it.” If you are applying water into the fire room with a 1¾-inch line and there is no improvement or conditions get worse, that’s a good sign you need a larger attack line or coordinated ventilation or to mount a defensive attack until you can get a good knockdown.

Extinguish the Fire

To effectively wrap up your incident, you must extinguish the fire by hitting the base and overhauling hot spots. Once you sized up and located the fire, identified the flow path, and cooled the fire, it’s time to extinguish it. You may have cooled the fire room from the outside or from the interior hallway prior to this point. Once the base of the fire has been extinguished, your IC may mark the fire as under control, depending on your department’s procedures.

This stage involves hitting the fire at its base to extinguish the fuel load and includes overhauling the structure to ensure no hot spots or hidden fires remain. Overhaul is just as important as any other phase on the fireground. No one wants to be the crew or shift that has to go back to the scene because of a smoldering joist or a smoking stud.

Use a thermal imaging camera and pull away the ceiling/wall coverings immediately over the fire and assess for heat. The caveat to this is your fire investigator may appreciate it if, once you have controlled the fire and begun overhaul, you let him know this and allow him to take photos/investigate prior to pulling down the ceiling that is above the point of origin. You may need copious amounts of water if fire has extended inside heavy timber material; Class A foam may assist you in soaking down persistently hot materials. Overhaul is tedious and physically demanding work, but it is necessary to ensure complete extinguishment.

Rescue

Rescue is the most important fireground task. The entire house could burn to the ground, but if you managed to rescue trapped victims, then your incident response was a success. Rescue is an action of opportunity. OSHA 29 CFR 1910.134(g)(4) states you must have an equal number of firefighters outside the structure ready to go in as you have working inside the structure. There is a minimum of no less than two firefighters inside the structure. The exception used in this scenario is when a known rescue will be performed.

When a known rescue is to be performed prior to other units arriving, your IC must ask the following five questions:

- Do we know where the victim is?

- Is the victim in an area considered survivable?

- Can we access this victim under current conditions?

- Are the resources on scene to bring this patient out successfully?

- Does this rescue have priority over other trapped occupants?

You must answer these questions to perform a rescue. You must know where the victim is—that he is in a survivable space—and that you have a clear path to the space and a clear exit from it, whether it is a window, exterior stairs, access to an exterior door, or a combination. Also, you need to have sufficient staffing to drag, carry, or pull the victim out of the structure. Know your crew’s limitations.

Finally, in a multiple-occupancy dwelling fire, consider whether this victim is your highest priority compared to rescuing others. There is no right answer to this last question, but certain factors should weigh in on your decision.

An example on prioritizing rescues comes from studying high-rise fires. In a 30-story high-rise apartment building, a fire that started on the 20th floor will immediately endanger everyone on that floor, so rescues near that fire take priority. After evacuating that floor, clear the floor above it. You then would skip to the top and begin searching those floors. One would suppose that most civilian casualties occur on the fire floor. The reality is that most fatalities occurred on the top two floors because of the rising superheated gases.

A rescue team must be equipped with a good complement of tools. A three-member company might bring a water can, irons, webbing, a backboard, and a search line, depending on the size of the building. A water can may immediately improve your situation should you find yourself trapped because of changing conditions. You can use the irons to force any doors and to also force your way through a wall should your exit become blocked. You can use the webbing and backboard to secure your victim and drag, carry, or push your victim to safety. In this scenario, you can bring in a search line because you are the only crew on scene and do not have a hoseline. If you become disoriented, there would be no other crews or landmarks for you to use to safely find your exit. A search line may seem like a hassle, but when you need it, it can make the difference between life and death.

Salvage

Although not essential to the pragmatic side of fighting a fire, salvage is key to keeping your community happy and, in some cases, it is the only way we can help our citizens. When fighting a defensive fire that has not yet reached a portion of the structure, it can be a blessing to attempt to salvage memorabilia and expensive portable items during your primary search. To us as firefighters, it may not seem like much, but if one of our homes caught fire, we would want them to save as many of our irreplaceable objects as they could.

Salvage additionally includes preventing the damage caused by our use of water. Use salvage tarps to cover furniture or create water chutes or use transfer pumps to assist the residents in pumping water out of their basements.

As an IC or a firefighter, you must continually assess the scene and look for signs of collapse, flashover, and other hazards. By mastering a systematic approach to firefighting, you can adapt to any conditions and make the right decision.

References

United States Fire Administration. Summary Incident Report: January 4, 2022-April 15, 2022. https://bit.ly/3xEpjze.

Fire Safety Research Institute. Study of the Impact of Fire Attack Utilizing Interior and Exterior Streams on Firefighter Safety and Occupant Survival. (August 1, 2014). https://bit.ly/3jTI9Ky.

Fire Safety Research Institute. Impact of Fire Attack Utilizing Interior and Exterior Streams on Firefighter Safety and Occupant Survival: Water Mapping. (October 2019). https://bit.ly/3JW2b1u.

Fireengineering.com. David Dodson: The Art of Reading Smoke (June 27, 2014). https://bit.ly/3uVw7qp.

Fire Engineering. What We Learned: Best Practices for Tackling Fires in Balloon-Frame Construction (August 2020). https://bit.ly/3JVBPNd.

Fire Engineering. Identifying Building Layouts and Hazards from the Outside. (January 2021). https://bit.ly/3rFM4Pl.

Fire Engineering. The Engine Company: Flow Paths and Fire Behavior. (October 2015). https://bit.ly/3EquXX7.

RYAN PETSCHE is an acting lieutenant and aspiring officer with the Burlington (IA) Fire Department, where he also serves as a paramedic.

CORRECTION (8/24/2022): Initial count for LODD directly from structural firefighting was incorrectly gathered and stated as 13. The article has been updated to reflect the correct number. We regret the error.