By CHRIS TOBIN and LEX SHADY

Consider the following: If you were lost in a blizzard on a treacherous peak, what would you rather be, a mountaineer or meteorologist? One is expertly familiar with the conditions, the other with the geographical environment. The answer is you would want to be both—you can’t fully understand one without the other. Unfortunately, as firefighters, we often find ourselves being only the meteorologist—in other words, we’re highly skilled at understanding fire behavior but not how the environment it’s in affects it. This is most apparent when looking at fires in legacy buildings or structures built prior to 1940.

- Main Street Firefighting: A Modern Take on Legacy Buildings

- The Fog of the Fireground: Know Your Buildings

- Building Construction Review

- Launching a KbyG Mentality on Gathering Building Intelligence

The two most important subjects a firefighter should know expertly are fire behavior and building construction. This is based in the pragmatic reality that conditions dictate tactics, while construction dictates strategy. No two aspects of firefighting influence outcomes on a fireground before and during more than the conditions we’re met with and the environment they occupy. Half of the answer to that equation is water. The other half, the building, is nonnegotiable, and the building has the final say.

Place Blindness

Today, firefighters have libraries of fire behavior data at their fingertips. Visit Underwriters Laboratories’ (UL’s) Web site, and you’ll have access to hours of information on fire conditions provided by constantly updated studies. Our fire academies teach the skill of reading smoke. We are trained early on to recognize dangerous conditions and teach our command staff to develop strategies based on checklists. However, the actual building is rarely mentioned. Ironically, this has led to firefighters who are expertly familiar with conditions but are unfamiliar with their environment.

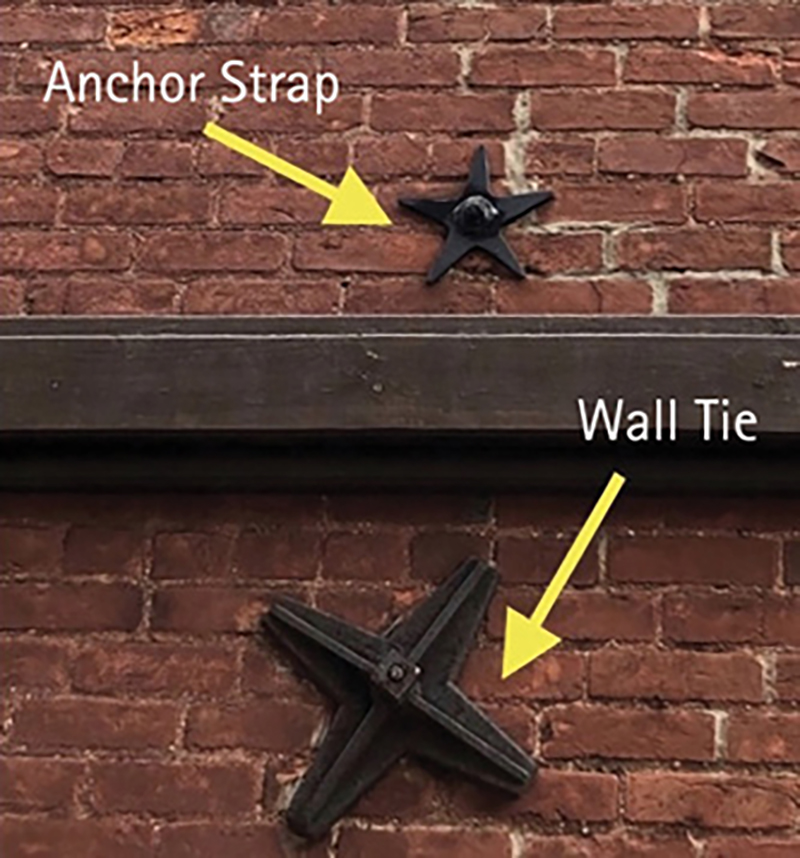

The fire service is suffering from “place blindness”—the inability to orient yourself to your surroundings. The underemphasis on training, particularly in legacy building construction, has become extremely apparent, so much so that we’ve subconsciously become blind to these buildings even though we see them every day. Instead of “missing the forest for the trees,” we instead just see a forest and miss the actual trees. These buildings have a language in the form of details and subtle clues, both of which we’re becoming incapable of understanding. A perfect example is structural stars that tie masonry walls together (photos 1, 2). Most firefighters have been taught misinformation for what they’re seeing if they catch them at all. The smaller star bolts are assumed to just be decorative but are actually tied into a joist or rafter by thin metal strips. These are often confused with larger anchor plates attached to rods running the entire span between walls they pull in. The rarity of legacy fires combined with dwindling building stocks and the proliferation of modern lightweight environments have made legacy buildings easy to forget—that is, until one is on fire. “Main Street” fires continue to show us loss after loss of legacy buildings. This begs the question, have we become ignorant spectators in our own arenas in situations that require skilled athletes? The arena in question is the legacy building and the space in which tenable conditions exist.

(1) Photos by authors.

(2)

There’s a saying, “All fires are the same,” which is true—that is, until you put one in a building. Once you add geometry to the equation, the variances increase exponentially. We must understand the materials and hazards inherent to the construction to develop strategic foreseeability on the fireground. Those who’ve undervalued this notion have failed to recognize that it’s the one variable of the equation over which we have no control while simultaneously having preexisting information—in other words, we can do nothing about building problems, only problems inside a building. And one of those two things was present long before we arrived. The solution is a choice, and it’s a simple one: Immerse yourself in your environment, your buildings, and your “arena.” Not doing so is akin to producing a sailor unfamiliar with the sea or a teacher unfamiliar with the classroom. Neither will be successful for lack of skill but for lack of awareness in their surroundings.

Unfortunately, this is the outcome of many fires in historic districts, main streets, and older buildings across America (photo 3). The result is often an empty parking lot, the building never to return. Even worse are the tragic collapses or related injuries that catch firefighters off guard. To be truly effective, we must understand the buildings we operate in and around, not just what’s under construction or the cliché of the “modern lightweight” building. This has led to the unfortunate tendency of fighting fires in legacy buildings from a lightweight construction mindset, favoring a defensive posture on arrival, as if nothing is to be gained. That may be the case when you’re used to oriented strand board (OSB) decking on trusses, but these are dimensional joists or rafters under 1 × 6 plank decking. Showing up to a building of legacy construction with a modern construction playbook is not effective in saving property or lives at risk, nor does it produce desirable outcomes for our taxpayers. These buildings may be older, but they are stronger and offer opportunities for interior operations that modern lightweight buildings don’t, especially roof work. The environments in legacy buildings are also a unique category because the hazards of modern furnishings are combined with older construction; this sets up an unfamiliar aspect for most, and it’s also the one environment UL has not specifically studied, like fires in modern construction.

(3)

Early on, we teach recruits that there are three priorities on every fireground: life safety, incident stabilization, and property conservation. Doing so in this manner without a deeper context can lead to a mindset that these buildings aren’t worth taking a risk for, and we must understand that these buildings are a higher priority with their historical and socioeconomic value. No property is worth injuring firefighters over, but the buildings on your Main Street must be placed higher on the list for property conservation than most. These buildings aren’t just revenue-producing businesses; they can also be taxpaying homes on the upper floors and, most importantly, a town’s identity. When “Small Town USA” loses its Main Street, there is no more “town”; there’s no more focal point of social events, the business owners leave, the post office closes, and the festivals move to the fairgrounds outside of town. The fact of the matter is dog parks and community gardens don’t attract people like a row of 20th-century brick and mortar. A fire on Main Street requires showing up with a plan that saves instead of one that settles.

To make informed decisions on arrival, we must have prior knowledge combined with an expert level of familiarity with legacy construction. This is only possible with the perpetual study of the environment in which you work. Just because you’ve been in a building dozens of times for emergency medical services runs or automatic alarms doesn’t mean you actually know the building, just its layout. That would be akin to saying you know the entire forest just by being familiar with one trail inside its boundaries. Don’t fall for lazy perception that leads to complacency based on false confidence. Often, we find ourselves seeing the building but not understanding what we’re looking at. We need to develop the skills of looking at buildings with a sort of “X-ray vision.” We need to know what lies behind a wall and beneath the roof. To predict how the building will react to fire, we need to understand how these components transfer loads so we can effectively triage our environment. From the street, some are obvious, others are not so much, and some are impossible without preexisting knowledge of what’s behind the door. Now add smoke, fire, and a possible life hazard, and you’ve created a massive challenge.

Make the Street Your Classroom

The question then becomes, how do we develop the knowledge, skills, and abilities required to read legacy buildings (photo 4)? The science behind training tells us the best way to learn is through deliberate repetition. However, how do we accomplish this with building construction when there isn’t a “skill”? The answer is through visual, tactile, and kinesthetic learning. Visual learning is obviously the first and easiest way. Simply get out and look at your buildings. Once there, you must identify the problem you’re trying to solve: a deeper understanding of a building vs. vague recognition—in other words, applying the “why” to the “what.” Andragogy tells us that adults only want to learn something new if it addresses an issue that solves a problem. In this case, the issue is simply being more than just aware of your environment—instead, having the required knowledge to interpret details. Walking your streets provides a huge amount of usable information. Talk with property owners who have very specific details you’d never get otherwise. If you see something unique or important, take photos, and pass that information on to the other crews.

(4)

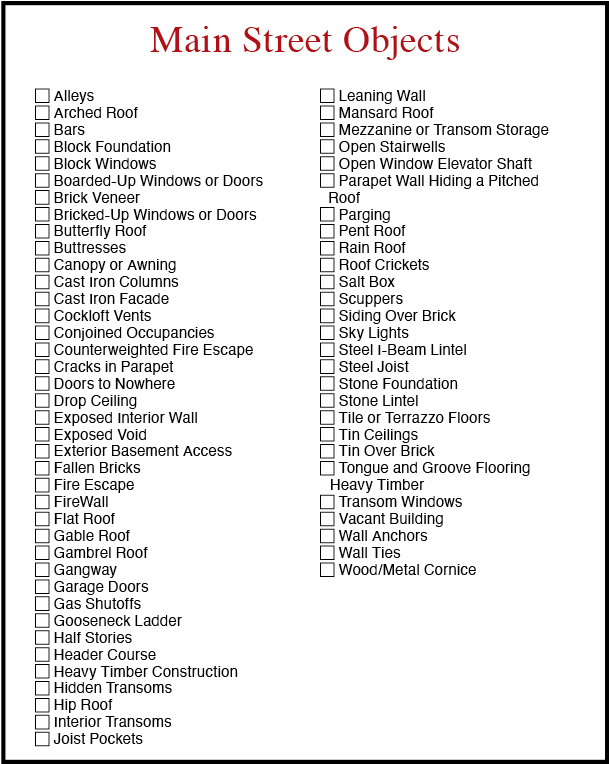

An easy drill to do with your company is a “scavenger hunt” (photo 5). Create a list of common items you’ll find in legacy buildings such as structural stars, header course, bars or boards, stairways to nowhere, cockloft vents, transom windows, tin ceilings, and so on, and give the list to your crew and see what they can find. This serves a dual purpose: It allows older members to speak on their experiences in the buildings you’re studying and allows newer members to practice identifying real-life visual cues on the buildings to which they will be responding. If you’re learning building construction in a book, you’re learning on a generic level. If you’re learning building construction in your streets, you’re learning it on an endemic level.

(5)

Another overlooked aspect is vacant buildings. Try to ascertain where your unhoused population resides in these buildings, what’s safe to enter, and what’s deemed derelict. Keep in mind that things change after dark; it’s a good idea to understand how your local population ebbs and flows depending on what time of day and year it is.

Tactile aids are the next step in the learning process (photo 6). There’s a saying, “It takes two bricks to kill a firefighter: one to knock off their helmet, the other to kill them.” You’d be amazed how many people have never actually touched a brick. Pick up a brick and pass it around your crew so they can understand the weight that can collapse down on them. Have them hold a legacy and lightweight 2 × 4 side by side so they can appreciate the difference. Show them a small section of a built-up roof decking, plaster and lath, and different types of beams compared to an OSB I-joist. Pass around structural star wall ties and window sash weights, which don’t exist in any training tower and must be brought in from the actual environment (or you must go to them). Getting your hands on the building’s components will help connect what has been taught in class, what you see on the streets, and the material itself. Independent illustrations in a book don’t show you how these parts all work together when constructed. Most students can identify a single column, joist, or the decking but have no notion of the hierarchy of collapse when it comes to structural components or the ability to determine load exterior-bearing walls.

(6)

Finally, the best way to acquire a skill is through kinesthetic or hands-on training but, most importantly, deliberate acquisition. How do we accomplish this in building construction? Through acquired structures. We can learn a lot with an empty building, no fire, and some hand tools. A department that takes training seriously will have a database or list of available buildings slated for demo that it can use for training. This process is fairly simple to set up through the county accessor or municipal building division. Encourage your fire academy, whether municipal or regional, to take its recruit classes around in a bus to different buildings when learning about construction types, the objective being to enhance the book material with realistic examples.

Another important aspect of this training is to have an instructor with a deep understanding of building construction and fire experience. The perspective of this individual pertaining to what students are looking at is invaluable. Another option is postfire walk-throughs, which are a huge benefit for younger members to see the path of fire travel, the effects of fire damage, and how structural components become weakened or fail.

Use the Building for What It’s Worth

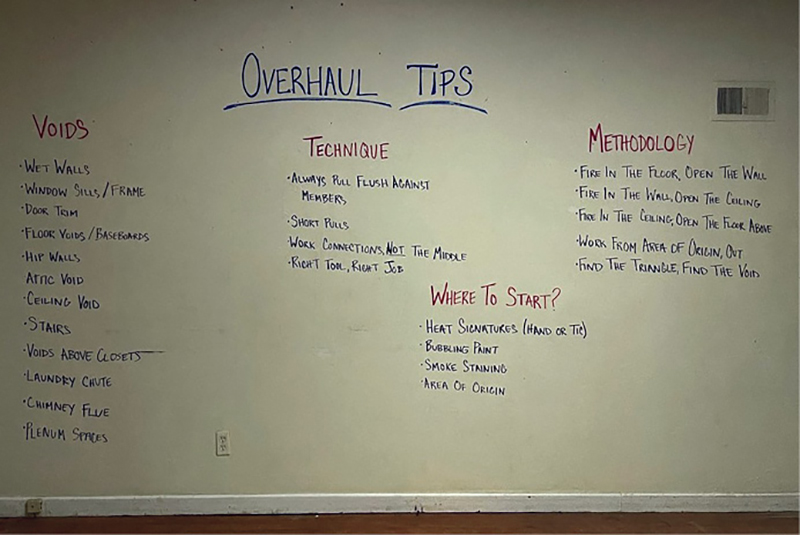

If you have the opportunity to train in an acquired structure, whether you burn it or not, open it up first before doing live burns or rapid intervention team drills. Most importantly, have a clear learning agenda. Conduct training in a disciplined and knowledgeable manner rather than sending your members in with tools and letting them freelance overhaul. Move with a purpose but, even before that, hold them up just inside the door. This is where most miss a golden opportunity. Using the walls, turn your building into a “3-D classroom.” We claim to be professionals, so discuss what it means to perform overhaul in that manner. Explain the goal of overhaul and how to perform it. Write out overhaul tips on the wall such as where voids are commonly located, where to start, the tools to use, the techniques, and the methodology (photo 7).

(7)

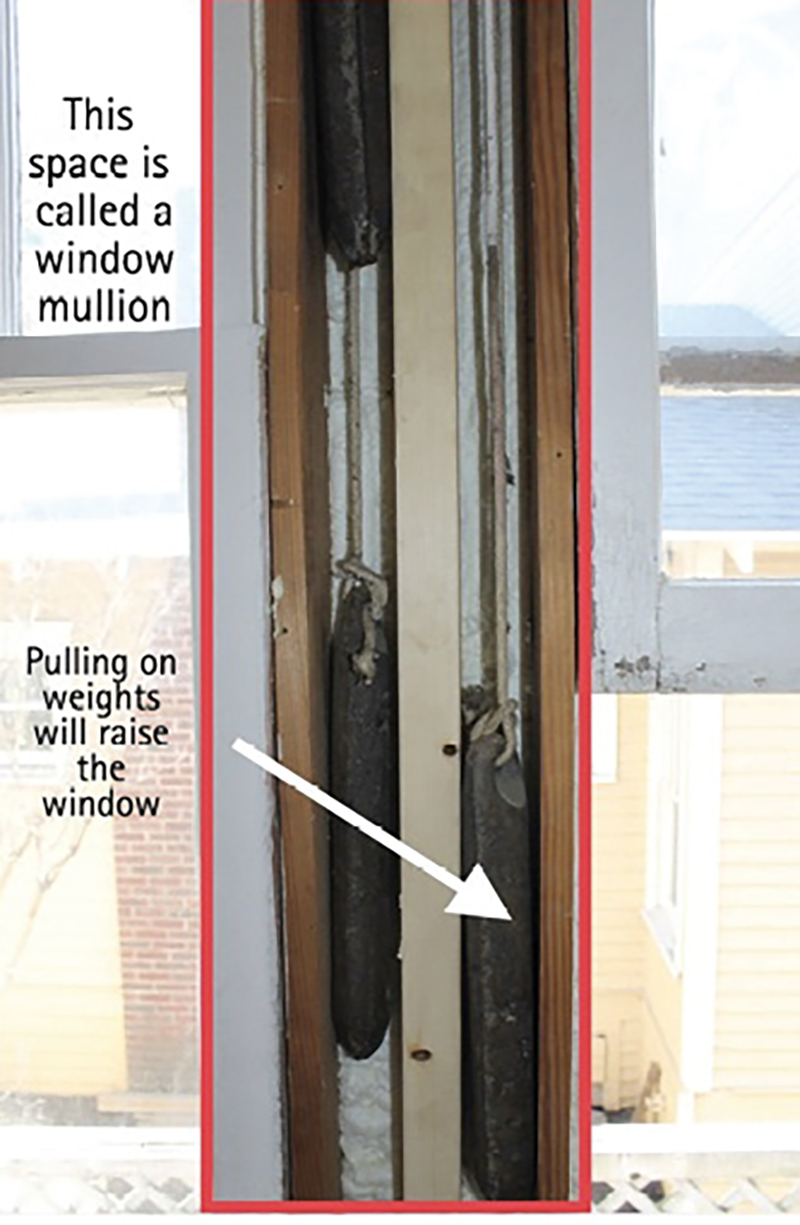

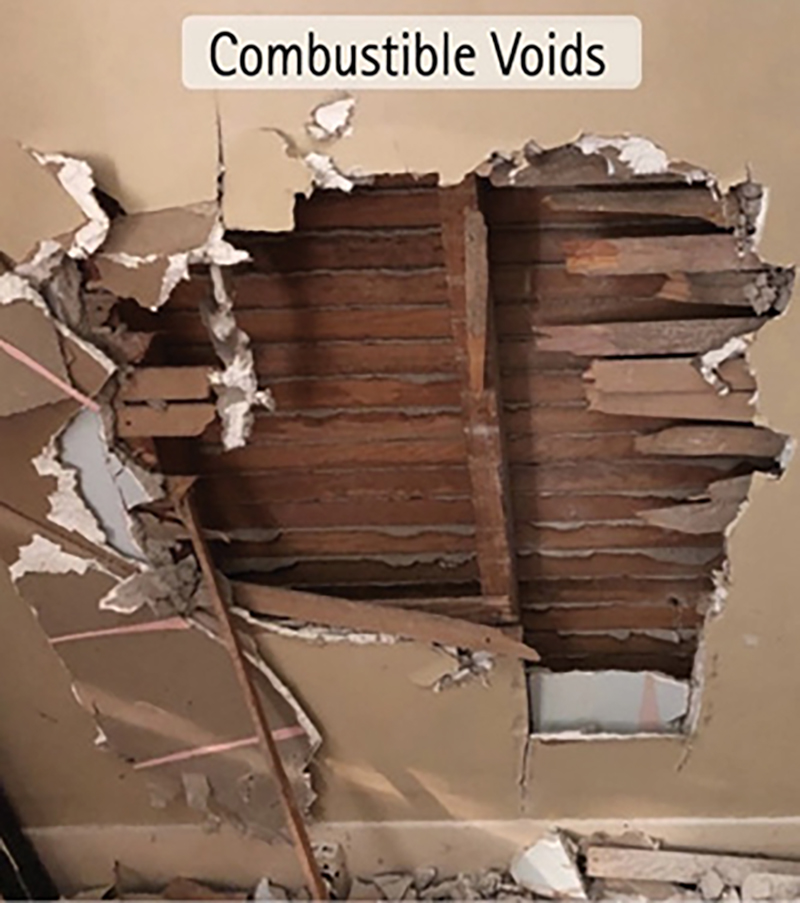

Next, open a wall on the opposite side of the room so students can see and understand the goal (photos 8, 9). Begin by showing and defining the common voids found in legacy construction. Some of the main ones to include are window voids, wet walls, knee walls, and stairway voids. Explain where you will find a window balance and that it is the mechanism for raising and lowering windows. In legacy homes, these are typically lead weights weighing anywhere from three to eight pounds. Help students understand that, even if the window has been replaced with a modern window, the weight can still be found in the void space. Explain what a wet wall or pipe chase is and how they’re found in bathrooms and kitchens to conceal the plumbing. Show the importance of checking these areas for fire extension when the fire has been nearby.

(8)

(9)

Talk about the voids on each side of a half-story called “knee” or “hip” walls, which average two to three feet high and are in place to close off the room where the sloping roof meets the floor line. This, in turn, creates a triangular void space on either side of the room. These spaces are then commonly used for storage accessed through a door or panel opening. Now, show them the third void in a half-story—the attic—and explain how these three voids can have fire behavior independent of the living space. Point out soffits above kitchen cabinets; heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning plenums; and voids under stairs. Have a discussion on why fire under the stairs is hazardous—that, as we know from wildland fires, fire travels faster up a hill and that the stairs are essentially an interior hill.

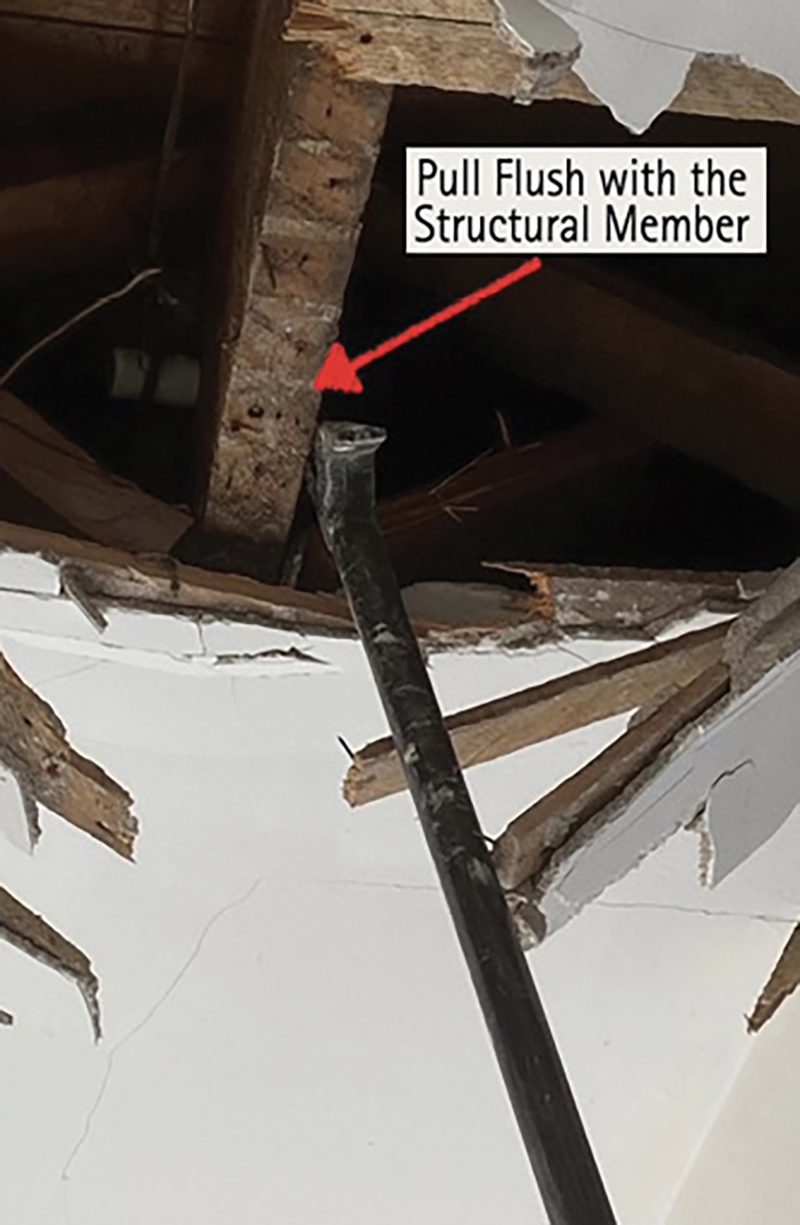

Then, once they understand the why and the what, give them a tool and explain the “how” (photos 10, 11). Show the difference between the flat and beveled side of a roof hook and why that matters. Discuss the difference between cutting and prying tools. Every minute detail you can share, such as pulling flush along structural members at connection points, will make overhaul more efficient. Attempting to pull lath in the middle results in a rubber band-like effect rather than working one connection point. This principle applies whenever you open up anything, including baseboards and trim. Demonstrate working together when pulling ceilings in parallel—and not perpendicularly—to ceiling joists. This is where students can compare and contrast what tools work better or best for what tasks.

(10)

(11)

A flathead ax is great for forcible entry hits, but it loses value to spiked tools such as a halligan or pickhead ax when used on the interior when it comes to split striking trim or baseboards. You can compare the capabilities of a metal roof hook to the limitations of a standard pike pole. You cannot practice certain techniques such as ceiling purchase points; swinging axes in constricted, low-visibility environments; how to best remove doors for covering holes; and the laborious task of floor removal in a training tower.

Finally, after some introductory practice, give them a specific task to accomplish. Avoid a general chore like “pull the ceiling.” Rather, tell your members to “trim a window” or “clear two stud bays” so they understand not to leave plaster and lath hanging haphazardly. Have them find the wet wall in the bathroom and expose the pipe chase. Explain why you should pull the baseboards before the wall. Go outside to pull the gutters and flashing to see the soffit void in the roofline; this is where students can learn about exterior voids. As St. Louis (MO) Fire Department Captain Greg Redmond teaches, grab a can of spray paint and give students visual cues of where to start the overhaul process (photos 12, 13). Tell them, “Go as far as the char” or “Open until there’s good wood.”

(12)

(13)

Overhaul is becoming a lost art, so take this opportunity to both learn the parts of a building and perfect their movements with the tools. All these skills can only be practiced in a real building, the only limitation being when the real estate runs out—hence, the importance of taking full advantage with the maximum reps and sets for your students when the opportunities arise.

Overhauling for Extinguishment

An unfortunate by-product of modern construction has been the misconception that overhaul is some boring postfire chore. This manifests itself before the fire as a reluctancy to train on proper techniques because it’s not seen as important or particularly valuable and then, during the fire, as subpar reactionary efforts that seem to never be ahead of the fire. The notion of overhaul being discounted to just something that’s haphazardly done after the fire is out couldn’t be further from the truth. Anyone who’s had the luxury of experiencing pipe chases, cocklofts, and knee walls will tell you otherwise. This devaluation of overhaul, combined with the era of declining fire, is what is meant by overhaul becoming a “lost art.”

In legacy construction, overhaul is a huge factor that makes or breaks an outcome. It’s the difference between crews being pushed back down the stairs in a Cape Cod bungalow and whether a row of Main Street shops is held at a fire partition. The reality is that overhaul in older buildings is done aggressively as the fire attack is progressing forward, working concurrently with extinguishment to support or directly access the fire itself.

Departments with prevailing building stocks of legacy construction will have, by necessity, a proactive overhaul mindset. This manifests itself by personnel always coming off the truck with a hand tool or having a rig set up with tools in the cab, ready to go on arrival. Proactive truck work is another hallmark of a strong culture, especially laddering and roof operations.

Prior to arrival, take into account the reflex time of roof work so you’re not playing catch-up on a rapidly extending void space fire. Truck positioning needs to be spot on for immediate roof access rather than waiting to be told to make a raise. Top-floor fires in older buildings with flat roofs must have a roof inspection to, at the very least, rule out pipe chase and cockloft extension. The only way any of this works is by having firefighters with a deep understanding of their buildings and the ability to anticipate where the fire has been, where it’s at, and where it’s going.

The goal is simple: Become the firefighter with the strategic foreseeability to avoid being lost on the fireground. Like the mountaineer vs. the meteorologist, it’s best to have a holistic set of skills so you can connect your environment with your conditions. This allows you to make an informed decision based on feedback from both ends of the equation. Regardless of department size or response, buildings require your having an intimate knowledge of their construction for your success on arrival.

CHRIS TOBIN is a firefighter assigned to St. Louis (MO) Fire Department Rescue 2.

LEX SHADY is a firefighter/paramedic with the Richmond Heights (MO) Fire Department.