The fire department exists to save victims. Buildings and personal possessions can be replaced, but people and pets cannot. We have failed as a fire service to put things in perspective and adequately explain what our mission is and how we will go about it. Our demographics, our staffing, and our resources vary from area to area. How firefighters achieve our mission may vary, but our goal should not.

The Clearwater (FL) Fire & Rescue standard operating guidelines paraphrased below explain the mission on a single-family dwelling response very well and leave no room for debate:

Life safety is the highest priority at all structure fires. The potential for life loss is most prominent in residential occupancies. Fire personnel should conduct a search operation at every fire to account for any potential victims. This objective should be achieved through interior fire containment and primary search. All operational tactics should be assigned to support this strategic goal. We should address the rescue problem by a thorough interior primary search for life, focusing on the tenable areas adjacent to the fire area, the bedrooms, and the means of egress. In this type of structure, coordinated ventilation is critical in facilitating a primary search. Ventilation may be achieved through removing or opening selected windows where occupants may be located.

Now that we understand the mission, let’s go deeper into how we go about achieving it at the task and crew level.

Residential Structure Fires: Primary Search

A residential structure search team with a minimum of two personnel will enter the structure and conduct a systematic quick search for any savable occupants. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), since this is a hazardous environment, the searchers should stay in contact by voice, by touch, or visually. The fire conditions and the partners’ training level determine the contact method used.

The worse the fire conditions, the closer the searchers will want to stay together. The better the fire conditions, the farther they can safely be from each other. If a quick search is the goal, searchers can best do this if they can spread out and cover more area quickly.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

If two seasoned firefighters are working together and have for a while, they will likely anticipate what each other will do and will be able to search farther apart from each other, thus effecting a search more quickly. But if an officer has a new firefighter, he will likely stay close to him so that he can keep a close eye on the new member.

Tool Choice for Search

“Two hands, two tools” is true when walking from the rig to the fire building. But if the searcher has two tools in his hands, he won’t be able to search effectively. In my district, the second-due apparatus assumes first-due truck functions: forcible entry (if needed), search, ventilation, and checking for extension. The officer carries a thermal imaging camera (TIC) and a roof hook; the firefighter carries the irons.

For a search in a residential setting, the only two tools we need at a minimum are the TIC and the halligan. The halligan allows us to force interior doors and take windows if needed. Once the exterior door is forced, we don’t need the ax for the search. Likewise, we only would pull ceiling to check for extension after completing the search, so until then, leave the six-foot hook at the door.

Once primary search is completed and no victims have been found, the search team should relay this message to command: “All clear.”

Communication

Searchers should periodically call out to any victims: “Fire department! Where are you?” Remember, any victims may not know you are there or may be going in and out of consciousness. They may only have one chance to call out; be quiet and listen!

We must use clear, unambiguous, preset language for speaking at a fire. Saying “Over here” is not a good direction. We also must limit the talk between rescuers. Not only may we miss a victim calling out, it can be confusing when talking through a mask. “I’m on wall one” sounds a lot like “I’ve got one!”

Acceptable Phrases

Communication should be brief and clear, as follows:

- “Room is clear.” Expect the searcher to move up to the next area.

- “I’ve got a room off a room” means the oriented man may need to move to a forward position in a room.

- “Victim, victim, victim” means the objective has been found; now, find the best way out.

- “How’s the search coming?” means how much time will it be until search is finished? Don’t just answer, “Good.”

Location

Be specific and say, “Wall 1, 2, 3, 4”; “2-3 corner”; or “3-4 corner.” The numbers start at wall 1 in the direction of travel in which you start in the room (right or left hand). Vague directions such as “Over here” do not give good directions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Search Patterns

Source: Coleman, John. Searching Smarter. Fire Engineering Books & Videos, 2011.

Residential Search Options

Searches go much faster if you search with two firefighters vs. three firefighters. Logically, more people would enable areas to be covered more quickly, but more people require more communication. In search, especially with low to no visibility, communication is the biggest time waster. Depending on apparatus staffing, you may have one team or two teams to perform search. If you have a three-person rig, the officer and firefighter are the search team; the driver/engineer will be the outside vent man. If you have a four-person apparatus, then the officer and nozzleman will be the inside team; the engineer and irons man will be an outside team.

Residential primary search has three options: hasty/dirty search, oriented search/split search, and vent-enter-search.

Hasty/Dirty Search

This is used when a fire unit arrives on scene and there will be a significant delay before the arrival of the next-arriving unit, as may happen in rural areas or if the stations are spread out. In this case, we must address the fire problem first to buy us more time and stabilize the incident. The hoseline should be stretched to the fire and the fire knocked down.

At this time, the nozzleman can pin the line and allow the officer or backup man to search the fire area first and then search off the hoseline back toward the front door, closing bedroom doors to maintain tenable space until another crew can search the rooms. Crews must have this plan in place before the incident. They should practice pinning the line and determine how the backup man and nozzleman will communicate and search off the line (photo 1).

(1)

(1) Photos by author.

Oriented Search/Split Search

An inside search is the preferred method of search if there is only one search team. If the hoseline is already in place, follow the line to the fire to ensure it is in place. The reason is that the oriented search team typically enters from the front door, which gives easy access to the whole house. Although the largest percentage of victims are found in the bedrooms, a large number of victims are found between the front door and the fire. An oriented search puts the searchers in the best position to find victims. When determining where to search, we want to get to the areas where victims are in the most danger and, after that, where they are most likely to be. A good rule of thumb is as follows:

- On the fire floor, you must go to the fire and then search out from there.

- When not on the fire floor, the search should start at the point of entry.

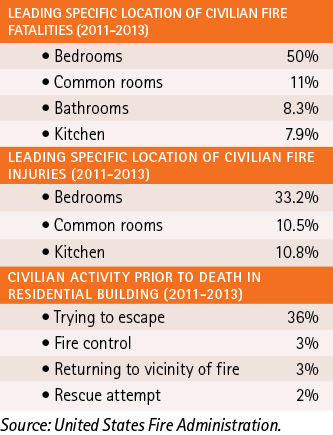

Once the search team or the attack team clears the fire room, move to the bedrooms and clear them. By searching in this manner, we ensure that the line made it to the fire, we clear the area from the front door to the fire (where 36% of victims are found), and then we clear the bedrooms (where 50% of victims are found), according to the United States Fire Administration.

Search size-up is important. As the crew walks up to the building, we read the doors and windows. Front doors typically open to a common area such as a living room or family room (photo 2). These rooms usually have a double or large window. Single windows usually indicate bedrooms (photo 3). If it’s a two-story house, the stairs are usually near the front door (photo 4). High or small windows indicate bathrooms or counter height rooms such as kitchens. Look for the garage location as well. Typically, the garage leads to a laundry room or a kitchen.

(2)

(3)

(4)

Once inside, first, get all the way to the ground and look for life, fire, and the layout.

Life. If we see a victim, we must be prepared for a quick line of sight rescue.

Fire. We need to find the seat of the fire. Get below the smoke; often, as fresh air enters, it will be clear at the floor and we can look for the glow or follow the direction in which the air goes into the house to get an idea of the fire’s location. If the attack team is already inside, then you can follow the hoseline.

Layout. As soon as the hoseline opens up, we may lose what limited vision we have. Look below the smoke to get an idea of the layout and see if it matches your outside size-up (photo 5).

(5)

The oriented search divides the searchers’ focus into two areas.

Officer. The officer leads the search and drops the member into the room to be searched while he decides where to search and sets the tempo. The officer sets the priority on what to search first and subsequently to ensure all areas are searched. He maintains orientation, plans an exit if a victim is found, coordinates with attack, coordinates with the incident commander (IC), watches out for crew safety, and maintains crew integrity.

Figure 2. Civilian Fire Fatality Locations

Firefighter/searcher. He searches from the front door while the officer locates the fire, follows the officer’s direction, and searches the rooms as the crew moves through the house. He searches with his hands once in the room and leaves his tool at the doorway of the room being searched (photo 6).

(6)

The officer should be the lead for oriented search to allow him to set the pace; by leading, he reduces the communication needed. After looking for life, fire, and layout, the officer should move toward the fire. If the attack team is in place, then the search officer should make contact with the attack officer and confirm that the attack team has enough hose and water being applied to the fire and that the fire area has been searched.

If any of those areas need to be addressed, they should be addressed before the search team moves on. If the attack team has searched the fire area, the search team must be sure to come back and do a secondary search once the rest of the building has been searched.

If the fire room needs to be searched, the officer should search the fire room while the firefighter searches outside of the fire room. If nothing above needs to be addressed, then the search team should move toward the bedrooms. Once the bedrooms are all clear, the search team should systematically search back toward the front door. If the attack team has not already entered, the search team can report the fire location to the attack team.

Once the fire area has been searched, the goal is to get to the bedrooms as quickly as possible. If both search team members move in a single line, they won’t cover a large area. If possible, they should be offset to cover more ground as they move toward the bedrooms. Once the bedrooms have been identified, the oriented man literally dumps the searcher into the room to be searched. Then he quickly uses the TIC behind the searcher to call out the layout and the presence of any victims. As the searcher searches, the oriented man maintains a position from which he can monitor the areas where the searchers are working. He should search the common areas nearby, watch out for their safety and changing fire conditions, and identify the next area to be searched.

Because the officer/oriented man is maintaining orientation, the searcher can concentrate solely on the search. He can search the room as fast as possible, knowing that someone is in the hall, within voice contact, looking out for them. In addition, the searcher can leave the halligan at the door to the bedroom he is in, so he can use both hands to better identify objects in the room. If he needs the tool for any reason, the officer/oriented man is close by and can bring it.

The searcher must check behind doors, under beds, above beds to check for the presence of bunk beds, and in closets. It’s usually not necessary to search walls unless you are specifically looking for a window to open or to use for egress.

One misconception with oriented search is that the oriented man does not search. This is not absolute. The oriented man directs the search and maintains an overall big picture mindset. The searcher goes in each room and completes the search. If the conditions are mild, then the firefighters can be farther apart (voice or visual) and can split search or leapfrog rooms. In this case, the oriented man does actively search. If the conditions are bad or the searcher is new, the oriented man may choose to stay closer to the firefighter. In an area in which bedrooms are clustered together, the oriented man can search the hall and the bathroom while waiting for the searcher to finish the bedrooms.

Often, firefighters debate whether an oriented or a split search is better. An easier way to differentiate them is to compare them to junior varsity and varsity football teams. Both have their place and both are similar in how they are completed; the big difference is how closely the searchers stay together and how much direction is needed.

Maintain crew integrity through contact—voice (including radio), visual, or touch. The worse the conditions, the tighter the crew stays. The better the conditions, the farther away they can get to accelerate the search. Likewise, experience and training count. The more familiar the crew is with each other and the more trained and seasoned they are, the farther they can spread out from each other and speed up the search.

The ultimate goal of the search is to quickly locate and remove victims. We can do this more efficiently the farther apart we are. As listed above, it depends on the experience level of the members and the conditions of the structure. As we spread apart farther, we move from an oriented search to a split search (if we insist on calling it something). The officer or senior member is still responsible for all that is listed above; however, with a split search, the officer may be able to do those along with searching. In the split search, depending on the layout, the crew may leapfrog rooms, divide left side/right side, or split the structure in another way. When split searching is more common, it’s not odd for both members to carry a tool.

VES

VES is most often used in conjunction with the oriented search. One search team typically goes inside and the outside team completes VES. This is most common on four-person units and “true truck companies.”

Four common situations in which to use VES include known victim location, if the crew is split (two inside/two outside search), access can’t be accomplished by other means, and to clear possible tenable areas prior to going defensive. VES does not require rescue mode and is not used when positive pressure ventilation is deployed.

When performing VES, identify searchable spaces, coordinate with the IC, clear the window or door entry point, and observe/read smoke and fire conditions to determine whether to proceed with VES or not.

Before entry, sweep for victims and sound the floor before entering; if appropriate, sweep the room with the TIC. The first firefighter enters after performing a highly important sweep of the hallway for life and then isolates the room if possible. The other firefighter remains at the window and makes entry when needed, if it is a large room, if a victim is found, and if primary search can be continued beyond the door to the room. The firefighter at the door will size up the hallway and contact the IC to coordinate search, “IC from Engine 17 search, the hallway conditions are favorable; we are continuing the search,” at which time the second firefighter can make entry and assist with the search.

Focused search is another VES application—for example, where the victim’s location is known and the nearest entry is a window to that room. Another VES application is when it looks to be a defensive fire and making entry through normal means isn’t possible. In this case, we are searching for tenable space behind closed doors from the outside. While the ladders are going up, we can use VES to clear these bedroom areas (photo 7).

(7)

Commercial Structure Fires (Primary Search)

Nationally, it is recognized that there are fewer civilian fire deaths in commercial structures than in residential ones. Also, because orientation is much more difficult in a commercial structure vs. a residential one, firefighters must be careful. Because of commercial structures’ size and layout, the primary search often will take longer and need a larger number of personnel. Hence, in most circumstances, the most effective way to conduct a large rescue is to put the fire out first.

In some occupancies, such as nursing homes, with a large number of occupants, the rescue may be delayed. In such large occupancies, it may be advisable to isolate the victims within their rooms or corridors (shelter in place) and instead remove the hazard from the occupants.

When a search is initiated, a two-member (at minimum) search team will enter the structure and conduct a systematic quick search for any savable occupants. The search team should use a search rope, initiate the search on either the left or the right hand, and relay the search orientation to command. On primary search completion, relay to command that a victim has been found or an “All clear.” Commercial search options include team search, oriented search, VES, and large-area search.

Secondary Search (Residential and Commercial)

A minimum of a two-person search team will enter the structure and conduct a systematic, thorough search after the fire has been brought under control. Use a fresh search team to ensure it does not follow the same pattern. This search is to confirm that no other occupants are in the building.

As a fire service, we have failed to adequately explain and prepare our personnel for the mission of saving victims. By clearly understanding what we are here to do and how we will do it, we now can prepare better to go after them.

References

Clackamas Fire District #1, Milwaukie, Oregon. “Rescue & Search.” Truck Company Manual.

Clearwater (FL) Fire and Rescue. Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) 627, “Emergency Operations at Single Family Dwelling Fires.”

Firefighter Rescue Survey. http://www.firefighterrescuesurvey.com/.

Grant Schwalbe has been a firefighter since 1994 and is a lieutenant/paramedic on Engine 43 with Estero (FL) Fire Rescue. He is an instructor for When Things Go Bad, Inc. and for the Fort Myers Fire Academy.