VOLUNTEERS CORNER ❘ BY JERRY KNAPP

Every volunteer fire department has a variety of members with widely varying careers outside the firehouse, each bringing unique knowledge, skills, and abilities to the organization. This is a powerful advantage to organizations on and off the fireground. However, managing the members can be difficult. One problem volunteer departments face is qualifying their members with those diverse skills, backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives as tool and apparatus operators. Time is the enemy of all volunteer fire departments, so why burden members with silly requirements—e.g., do the evolution 10 times at 10 separate training sessions to be “qualified”? If members/trainees can perform the skill, qualify them, the sooner the better. We all learn at different rates; if your trainee demonstrates proficiency in three evolutions, why waste his time for seven more evolutions that have no training value and only delay the use of his skills for your department and the taxpayers? Your goal as a leader is to get your members proficient in the most effective and efficient way. Train to a standard, not to a time.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Truck Company Operations: Truck Tools

This article presents a simple but effective solution to train and qualify your members in a way that plays to their skill level, experience, learning speed, and ability. Most importantly, it is fair to everyone. They all know exactly what is expected of them to qualify and on the fireground.

The solution is based on three words: task, condition, and standard. Let’s look at them in detail and see how you can apply them to your company or department. Our example is qualifying an engine operator to supply water from a hydrant.

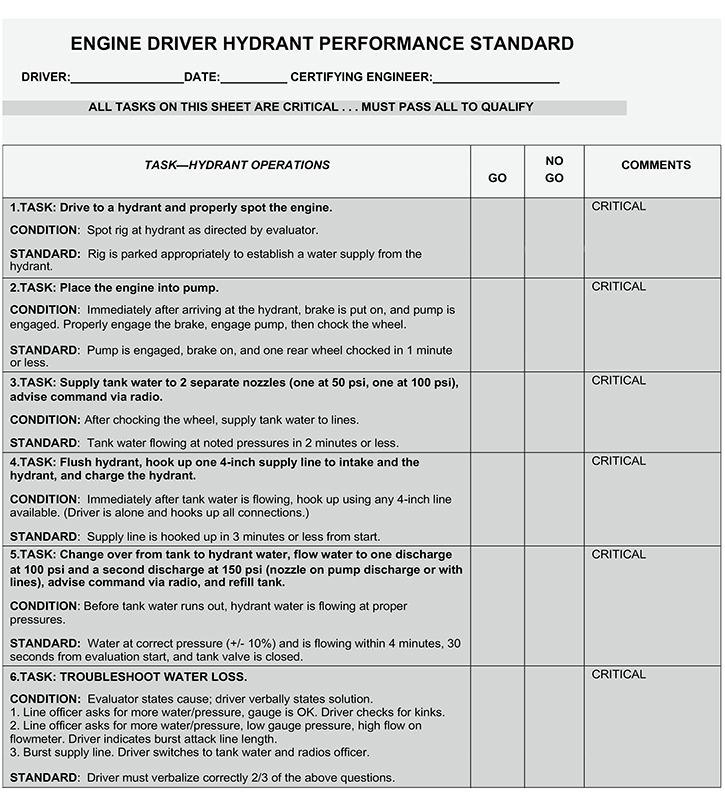

Figure 1. Driver Hydrant Operations Task Sheet

Task: Qualifying an Engine Driver/Operator

What is it you want your member to accomplish? Let’s say you are training a new driver/operator for your engine. The task (one of many to be fully qualified) is to establish a reliable water supply from a hydrant and flow water to the first two handlines at the correct pressures. The steps to succeed in doing this are the following: Stop the engine at the hydrant, apply the brake, put the pump in gear, safely exit the engine, supply tank water to the first two hoselines, flush the hydrant, connect the supply line, turn on the hydrant and switch over from tank to hydrant water, and troubleshoot any problems that interrupt the target flow to the nozzle teams. Once the engine has hydrant water, your trainee must supply water at the proper pressures to the two hoselines. This ends the evaluation. Figure 1 outlines five tasks that must be accomplished for success. The trainee also must know and be proficient in several implied tasks—e.g., spotting the engine in relation to the hydrant, putting the engine in pump mode, opening/flushing the hydrant, and calculating/understanding and providing proper pump discharge pressures using the engine controls.

Three Benefits

Your first-due area may require other specific tasks or procedures (e.g., drafting, tanker shuttles) that members must accomplish to comply with your local requirements and standard operating procedures (SOPs). The important concept is to get down on paper the steps your engine chauffeurs need to be proficient in to accomplish the task that supports the overall mission of life safety and fire extinguishment.

Defining the overall task (and implied tasks and the specific steps) offers the officer and the trainees several important benefits:

1. It provides a written guide that trainees can study and memorize so they can succeed on qualification or evaluation day. An officer’s job is to help make his subordinates succeed.

2. It provides you and the trainees a clear go/no-go analysis of their performance. If the trainees do not complete critical functions, you can give them a written performance analysis so they know where they need to practice and improve to ultimately succeed.

3. In coordination with your SOPs, it establishes a common method to help ensure company and department level success on the fireground.

Conditions

Under what conditions do you expect the trainees to accomplish the task? In the hydrant performance standard, the conditions may be a street and hydrant at a fire training center or in a safe place in your district. You also need a couple of firefighters to stretch the attack hoselines. For trainees, the two hoselines with different nozzle pressures are part of the conditions. If the condition is for two lines getting the correct nozzle pressures (they can be of different length and nozzle types), the trainees will demonstrate an understanding of friction loss; required pump discharge pressures; and how to regulate pressure and flow using the gauges, discharge valves, and throttle. When pumped at the correct pressures and acknowledged by the evaluator, this signifies the end of the evolution and evaluation.

You may choose conditions during daylight hours or at night, simulating a nighttime fire. You don’t need to lay a lot of hose; if other firefighters are not available, attach the nozzles to the discharge of the engine. An example of conditions is in Task 4 in Figure 1. The condition is that the driver/trainee alone hook up all connections immediately after tank water is flowing.

Standard

How quickly does the skill have to be executed? Almost everything we do in the fire service has a time component to it. In essence, faster is usually better. But, reality must play into your standard. A good way to set the standard is to have one of your drivers execute the task in a very deliberate and controlled manner, and time it. Use this number for your standard. This will give you a realistic time frame for your evaluation standard. Add some time to account for inexperienced operators if you choose. Once the realistic time standard is set, the trainee has a measure to judge himself against while he is preparing for the evaluation. In Task 5 in Figure 1, there are several implied tasks (e.g., close tank valve, open supply valve, regulate pressures) that are required to regulate the flow/pressure to different lines, but the standard is that they must be correct within 10 percent.

Task, Condition, Standard—what you end up with is a checklist of critical and noncritical functions that are necessary for your members to demonstrate proficiency with a tool or an apparatus. You can apply this principle to truck and rescue company operations, extrication tools, saws, and other tools and operations in which a firefighter or an officer must be proficient. This process is fair since you will use it as a standard competency test for all who want to become qualified to use the tool or drive/operate during emergencies. Regarding driving, the process described above is an example of one critical task that you expect a driver to accomplish. Other important criteria that you may include as prerequisites are formal emergency vehicle operations, driver training, parking, and obstacle courses. However, the tasks your department has deemed necessary for your local conditions/procedures can be specified and evaluated as described above.

Advantages

First, the task, condition, and standard method/model provides a fair and uniform system of training and evaluating your members. It eliminates friction that comes from statements like, “The captain does not think I am ready yet,” and fertile ground for cries of unfair treatment because of personality clashes, upcoming elections, or a myriad of other issues. Using a fair and reasonable standard also creates unity. Your members can band together and try to attain an established goal and work and train together to meet it. For the officers, it reduces the stress of qualifying and testing members who may be old friends or maybe not-so-good friends but have to work together. It gives members with different learning needs and methods a take-home checklist to study at their leisure and even walk through in dress rehearsals (together) or while training with other qualified members, relieving the officer of that time commitment.

For members who may have some experience with the skill, such as a career firefighter or an experienced firefighter in your department or a transfer from another department, it provides them with an opportunity to learn your methods and procedures so they can execute them as full team members. With some limited training, they can qualify and become valuable team members using existing skills combined with some supplemental training. For members who have some experience or who learn quickly, the task, condition, and standard method provides a rapid, fair way to be qualified without wasting precious time meeting some arbitrary and antiquated edict or dealing with officers with hidden agendas. If members need more time, it provides that too.

Possibly the most important benefit for the task, condition, and standard method is that it provides a reference of simple-to-follow procedures so your members can rapidly develop knowledge, skills, and abilities for tools and equipment such as extrication tools, saws, and medical equipment. It provides a step-by-step set of best practices not only for trainees but for experienced members as well. It can serve as an excellent refresher simply by having the member read the skill sheet; it could also be the basis for a company drill. As firefighting procedures, techniques, apparatus, and tools evolve and develop, it is a simple way to modify your qualification standards.

Another benefit of the task, condition, and standard-based performance sheet is that it enables experienced members to maintain their skills, which is an important goal.

It takes some time to think and work through, write down, and smooth out the details of task, condition, and standard. Remember, don’t get crazy with details; recognize specified and implied tasks, and highlight the important tasks necessary for task and mission success. This short-term investment of time will save everyone’s time in the future and help organize your company for success on the fireground.

JERRY KNAPP is a 44-year veteran firefighter/emergency medical technician with the West Haverstraw (NY) Fire Department; a training officer at the Rockland County Fire Training Center in Pomona, New York; chief of the Rockland County Hazardous Materials Team; and a former nationally certified paramedic. He has a degree in fire protection, is the co-author with Chris Flatley of House Fires (Fire Engineering), wrote the “Fire Attack” chapter in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II (Fire Engineering), and has authored numerous articles for fire service trade journals.