By Brett Snow

This article is atypical from what I have written in the past and certainly veers off from the common tactical-related topics. However, the nature of this article is too important to shrink away from. Nearing the end of a 32-year career in the fire service, I found myself needing to defog my lenses in order to get a better look at my life over the fire service. A size-up, if you will, of where I have been, where I am at, and where I am going. Not until then was I able to realize just how misaligned my path had been and how I had overlooked many life lessons. After developing a seizure disorder halfway through my high school years, I was turned away by the military, leaving the fire service to be the next best option. When I started out in the fire service, I was practically still wearing my high school graduation gown. In the summer of 1988, I began my career on a volunteer fire department while completing a two-year paramedic program. From there, my passion grew into an obsession where I then started working between two departments, instructing, and pursuing a higher education. Before I knew it, 25 years had gone by and I found myself being divorced for the third time, losing my house, becoming a part-time dad, and fighting for my sanity.

RELATED

My Journey Out of the ‘Darkness’ of PTSD

Living with PTSD: A Wife’s Side of the Story

Paul Combs Poster: Firefighter PTSD and Suicide

I Don’t Need That Resiliency Stuff, But My Firefighters Do

The following three years were spent blinded by anger and feeling powerless over the situation. Distraction consumed me each and every day, especially when I was at the firehouse. My final wakeup moment occurred during a response to an address on Drake Ave. During a Saturday in late 2015, I was detailed as the lieutenant on a truck where we were dispatched to a possible fire. On the way there I couldn’t remember how to get to Drake Avenue and why this street was so familiar. It wasn’t until we turned onto Drake Avenue when I realized my house was on this street, about five addresses down from where the call came in. I knew then that it was time to remove myself from the streets to reset my mind. During this time, I learned to surrender my life to God and accept His Way. I am now remarried to a wonderful woman, have my two boys regularly, am committed to the path of faith, and hope to continue into another purpose in helping first responders and their families, worldwide, better understand the life over the fire service.

Courage and the Limits of Control

I believe it is accurate to say that, through situational awareness, first responders are trained to be hard to kill along with the skills needed to accomplish the required tasks. Unfortunately, however, when it comes to stepping outside of our natural human responses, we are merely expected to do so. During my doctoral studies in Clinical Christian Counseling, I came across this quote by an unnamed psychiatrist: “An insane response to an insane situation is sane behavior.” Considering what we in the fire service deem as being normal behavior, I was compelled to reorganize this quote to fit that of a first responder. This is what it looks like: a sane response to an insane situation is insane behavior. Some can argue that first responders are conditioned physically and technically proficient, and thus that our fear is trained out of us. However, what happens when we fail to achieve the desired results on the fireground? Well, in most cases, we don’t have time to worry about that because we are having to hurry up and reset our minds for the next call. The reality is that first responders are going against every natural human response and then expected to slip back into a normal, everyday personal life without a scratch. The questions to pose here are: do we believe it is natural or supernatural to be able to push past the point of opposition marked by a strong urge to retreat? What about being able to separate ourselves from an emotion that would normally keep us from performing a lifesaving intervention? It is alternately tempting to simply label it “courage” and move on. However, courage is not the absence of fear; it is fear managed.

How then are we able to manage our fear? To say that fear is trained out of us would be quite controversial, as everyone’s threshold for courage/managed fear is stratified, immeasurable, and requires a unique center point of awareness between living or dying. This is unlikely to be achieved during training. Again, is having courage or being courageous natural or supernatural? What if we fail? Are we responsible? Do we blame ourselves? Are we to carry that guilt? To help answer these questions, consider these two Scripture verses: “For God has not given us a spirit of fear and timidity, but of power, love, and self-discipline.” (2 Timothy 7:1 NLT) and “This is my command—be strong and courageous! Do not be afraid or discouraged. For the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.” (Joshua 1:9, NLT). In other words, when we feel we have failed during a lifesaving action that was taken in direct opposition of our human nature, we are to remain blameless and nor are we expected to carry that guilt. Does this free us from having to know our job, or to strive for excellence? Absolutely not. It frees us from what is humanly unattainable, namely perfection.

Resiliency and Reflection

To look at our lives over the fire service—or a potential life to come—it is important to be aware of how rescue efforts can impact our minds and family. The concept of resiliency has hit the market and is becoming an acceptable pillar for administrators to use within their departments. Although this is an overdue and respectable concept, a deeper look is needed into the reasons behind the poor emotional and psychological pliability first responders tend to have between work and their personal life. We can help strengthen a structure to withstand the winds of a hurricane by installing hurricane windows and exterior shutters, but we often fail to understand the overall impact the flood waters, loss of utilities, and insufficient essentials may have on the individuals residing inside. When considering the high incidences of suicide, depression, and anxiety affecting first responders, we cannot ignore toxic thinking that is most likely stemming from an altered or false belief system. Additionally, it is important to recognize the necessity for first responders having to set aside emotions to perform lifesaving interventions, which then grows into an automatic response. Consequently, this same automatic response can bring about adversity as it transitions into our personal lives, creating a sense of disconnect or lack of compassion during times of emotional needs.

Furthermore, it is common to discuss the related structures in the brain, and how our bodies respond to traumatic exposure through the release of stress hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline. What is equally important is to know why there may exist residual stress following a traumatic exposure. According to the founder of the American Institute of Stress, Dr. Hans Selye, “Stress, in addition to being itself, was also the cause of itself, and the result of itself.” (Rosch, 2017). It is inaccurate to solely blame the traumatic event or situation for the stress response. Interpretation of a traumatic situation differs greatly from one person to another and therefore the reaction to the situation also needs to be considered within the development of a stress response. It is these interpretations that can strongly influence our belief systems, either positively or negatively, which then tend to govern our way of thinking and potentially resulting in chronic, stress provoking, and pathogenic recurrent thoughts.

When I would experience residual effects of my traumatic exposures, it wasn’t the actual situation that bothered me. It was how I viewed it afterwards. Did something go wrong? Was I responsible for the undesirable outcome? What if I am faced with the same situation again? Some of my greatest struggles in the fire service was maintaining confidence and battling self-blame. It only takes one fumble of the hose during a leadout or a failed attempt at forcing a door to negatively influence the outcome of a situation. If we do not use these moments to better ourselves, then it is the same as if it never happened. Additionally, it is important to know that we are only given the power to act and make choices, but we are without any power to decide the final outcomes, regardless of what we may assume. This same philosophy applies to our personal life as well. Therefore, before we act upon a situation, the following are some questions we can ask ourselves: Am I being selfish? Whose “way” am I choosing? How much control do I really have?

Communication and Temperament

One of the most profound commonalities when it comes to undesirable outcomes in both the fire service and in our personal lives is communication. Not only is it crucial to be on the correct channel, we must also know what to say, what not to say, and, most importantly, when to just listen. I have yet to read a report from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) where poor communication wasn’t part of the equation. In terms of our personal lives, if we are consistently on the wrong channel between us and our loved ones at home, then where will we turn? Most likely to our coworkers, because they seem to always be on our channel and understand our language. This inevitably leads to the rise of an emotional wall; overcoming this obstacle again and again leads to exhaustion, making it easier to migrate away from each other. I reached a point early in my career where any time there was conflict or communication struggles at home, it was countered by picking up extra shifts or meeting coworkers out for a cold one. It is easy to become frustrated in our personal lives by thinking that other people never understand what is bothering us, or to rationalize why I may have seemed uncompassionate and distant. It took me nearly 30-years to finally understand the reasons behind most of my disasters in life.

Besides having a long history living in opposition of faith, the reasons behind my career-long communication struggles at home stemmed from both their lack in awareness of what we truly experience as first responders along with a shared lack in the understanding of each other’s temperament traits. Before I began researching and learning about temperament, I carried the opinion that one’s skills and accomplishments solely rested on the degree of effort applied to an area of interest. However, this fails to explain the shortfalls of those not reaching their goals after substantial efforts, nor the lack of happiness and feelings of unfulfillment experienced by some individuals who prevail. An easy explanation can be obtained by the words of Paul in the book of Romans: “In His grace, God has given us different gifts for doing certain things well…”(12:6, NLT). A more complex answer would include our temperament. Temperament can be thought of as being the inner, immaterial programing uniquely designed to guide our responses to personal, social, and cultural environments. Evidence of an inner uniqueness can be found in the book of Genesis: “As the boys grew up, Esau became a skillful hunter. He was an outdoorsman, but Jacob had a quiet temperament, preferring to stay at home” (25:27, NLT, emphasis added). Having this unique programming also allows us to bring our gifted abilities to their fullest potential. Temperament is the foundation for how we are meant to be, which further governs what we are meant to do.

Personality, that which is observed about a person, is the expression of one’s temperament and is often incorrectly conflated temperament. A person’s personality can either be in harmony with their temperament or in conflict. As we progress through life, we are under constant exposure to environmental influences, shaping our outward self into a behavior that either remains consistent with our temperament or one that we discover produces less discomfort and more acceptance—the latter remains in conflict with our temperament, which may entail chronic stress, occupational dissatisfaction, and marital issues. For example; If an individual’s temperament traits were that of having little desire to be in charge or making decisions, how well should we expect this person to adapt to a supervisory role? Not that they would be considered incapable, but they may likely experience harmful, chronic stress and occupational dissatisfaction. These same concerns apply to one’s personal life as well.

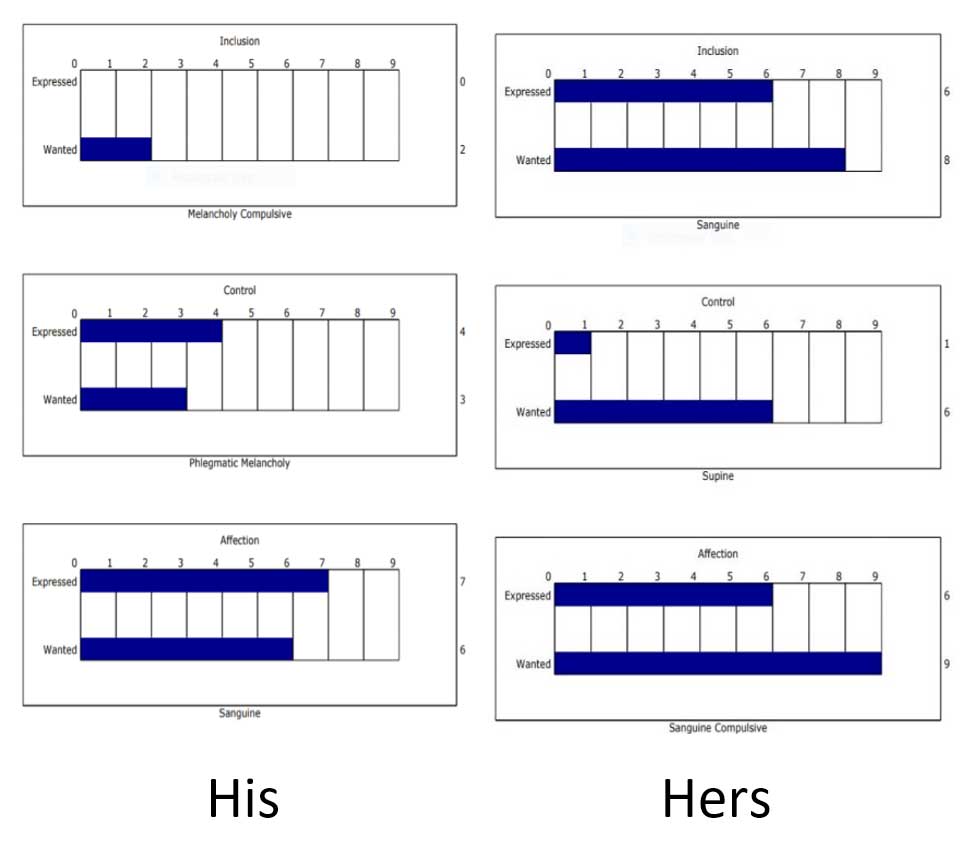

The above figure offers a comparison of what the temperaments of two individuals can look like when analyzed and placed side-by-side, highlighting their unique differences. The blue bars indicate the degree of needs and wants each person has in the areas of social interaction, desire for responsibility, and close family interaction. Knowing this information, which requires a much more detailed explanation than can be accomplished in this article, can help us better understand why we feel the way we do under certain circumstances. It can also help us understand how to strengthen our relationships at home and in the workplace and how to stay in harmony with our temperaments. Below are a few questions to consider asking ourselves:

- What do I know about my own temperament traits?

- What do I know about my spouse’s temperament traits?

- Am I in the right position/occupation?

- How is my life at home?

Finally, more attention needs to be given to spousal awareness. It is naive to think that only the first responders experience sleep deprivation, communication struggles, and emotional side effects, especially when couples join forces prior to being introduced to the life over the fire service. Marriage is a gift that requires gratitude and constant maintenance. Therefore, we cannot expect a marriage to survive when only one side is maintained. We can compare the participants to two decking boards where, if only one of them receives a protective coating, the neglected one will eventually start to warp and pull away, causing them to no longer fit together.

Choosing a career as a first responder is indubitably honorable and selfless, but it can also ruin every good thing in our lives if we fail to fully understand it. We are not designed to carry our yesterdays, nor do we have the power to decide tomorrow’s outcomes. In conjunction with being humble, we need to choose whose way of life is better to follow. Your own?

References

Paul J. Rosch, M.D. Reminiscences of Hans Selye, and the Birth of “Stress”. https://www.stress.org/about/hans-selye-birth-of-stress, 2017.

BRETT SNOW has more than 30 years of fire service experience, serving the past 19 years with the Chicago (IL) Fire Department.

More information: https://sl-ministries.com/

This commentary reflects the opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Fire Engineering. It has not undergone Fire Engineering‘s peer-review process.