By Ryan Kelley

Paramedics have long been dispensing naloxone to revive opioid overdose patients. A decade ago, when overdoses were less common, administering naloxone was a rare occurrence—a paramedic in a large urban area might have administered the medication to one or two opioid overdose patients a month. Today, paramedics are on the frontlines of a national opioid epidemic, and these same paramedics might care for three or four opioid overdose patients during a single shift. In some cases, the overdose patient may have already received naloxone from law enforcement or even a Good Samaritan.

Saving Lives or Stopping Death?

Preliminary statistics released last month from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed a decline in the number of annual overdose deaths (about 68,000 last year vs. 70,000 the previous year). It’s the first decrease in nearly three decades, and has been attributed to the expanded access and use of naloxone, as well as fewer prescriptions being dispensed for high-dose opioids.

To many paramedics, this statistic isn’t cause for celebration. They still respond to increasing numbers of overdose patients—naloxone at the ready. Once the overdose is reversed and the patient is stabilized, most will be transported to the emergency department, although some patients will sign a transport refusal. Either way, within a few hours of being revived, the naloxone that saved them from respiratory arrest is now ushering in uncomfortable—sometimes unbearable—withdrawal symptoms. Being “dope sick” often leads them to seek relief and they go right back to where they started: using opioids.

In fact, paramedics sometimes end up treating the same overdose patient several times in a week or even in the same working day. It’s a vicious cycle for patients and also for paramedics, who often come to experience symptoms of “compassion fatigue”—frustration, anger and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. For these frontline soldiers, the war against opioid addiction seems like it will never end.

In a recent episode of the EMS podcast The Overrun, paramedic and co-host Kevin Maza perfectly sums up the paramedic perspective on opioid overdose reversal: “I don’t think naloxone is saving a life so much as stopping a death.”

Breaking the Cycle of Addiction

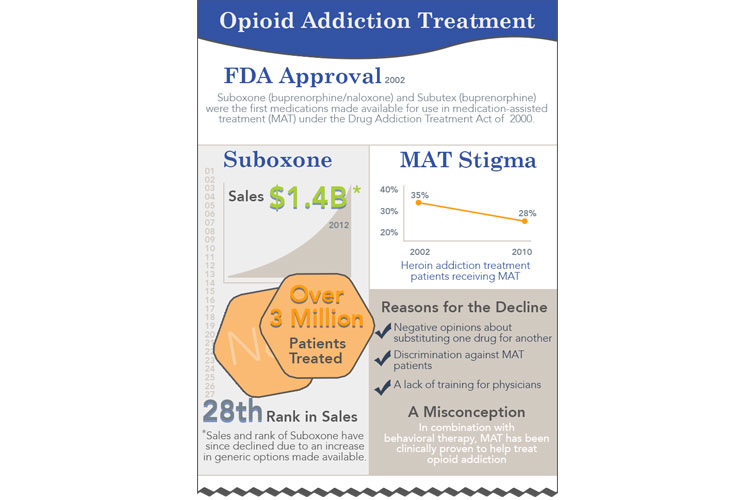

The only way to turn the tide on America’s opioid epidemic is to treat opioid dependency and addiction. The most effective treatment to overcome opioid addiction is medication-assisted treatment (MAT), a dual approach leveraging medication and behavioral therapies. The medication serves to block the euphoric effects of opioids, reduce cravings and minimize withdrawal symptoms. Counseling and behavioral therapy help to sustain recovery and prevent relapse.

In June, the health commissioner of New Jersey cleared the way for paramedics who revive a patient from an opioid overdose using naloxone to also administer buprenorphine. Along with methadone and naltrexone, buprenorphine is one of three medications approved for use in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Buprenorphine is a long-acting partial opioid agonist with a high affinity for binding to the body’s opioid receptors. When administered to someone revived from an opioid overdose with naloxone, buprenorphine is able to temper the effects of opioid withdrawal while at the same time competitively block opioid receptors from binding other opioid agonists with relatively lower binding affinity, such as heroin.

One critic of the New Jersey approach argues that the directive is “well-intentioned, but woefully insufficient.” He claims that buprenorphine “can be easily diverted or misused” and that it’s “never been, and never will be, a substitute for [treatment].”

Although it’s true that dispensing buprenorphine to patients has led to an increase in diversion and misuse, a 2016 report by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency acknowledges that most of this illegal use is due to “the failure to access legitimate addiction treatment,” and that this could be curtailed by “increasing, not limiting, buprenorphine treatment.”

It’s also true that buprenorphine alone can’t effectively treat opioid use disorder; but we know from the success of ED-initiated buprenorphine that it’s a good place to start. A 2015 study published in JAMA concluded, “ED-initiated buprenorphine, compared with brief intervention and referral, significantly increased engagement in formal addiction treatment [and] reduced self-reported illicit opioid use.”

It’s important to note that along with ED-initiated buprenorphine, patients were also given an appointment in the hospital’s primary care center. Protocols for paramedic-administered buprenorphine should ensure a similar commitment is in place prior to dispensing the medication. The patient must be amenable to treatment leading to full recovery, which requires counseling, behavioral therapy and social support.

A Window of Opportunity

Positioning a patient on a path toward recovery from opioid use disorder can’t be forced; a person must have the will and desire to change. Humans shy away from change, although cognitive theory tells us people demonstrate a greater readiness for change after sentinel events—unexpected occurrences involving death or serious physical or psychological injury. The brush with death of a revived overdose combined with the physical discomfort of naloxone-induced withdrawal symptoms certainly qualifies.

Paramedics are uniquely positioned as the first healthcare provider the patient encounters at a sentinel moment where they’re ready to change their behavior and commit to recovery. Therefore, every reversed opioid overdose is a potential opportunity to guide someone toward much-needed treatment for opioid dependency and addiction.

This window of opportunity closes as soon as withdrawal kicks in and they return to illicit opioid use. By holding powerful withdrawal symptoms at bay, buprenorphine becomes a tool that paramedics can use to keep the window of willingness to treatment and full recovery propped open a bit longer. In doing so, paramedics aren’t just stopping a death, they’re truly saving a life.

Ryan Kelley, NREMT, is a nationally registered Emergency Medical Technician and the former managing editor of the Journal of Emergency Medical Services (JEMS). In his current capacity as Medical Editor for American Addiction Centers, Ryan works to provide accurate, authoritative information to those seeking help for substance abuse and behavioral health issues.

RELATED