Chemical Spill Was Catalyst For Special Haz-Mat Training

After a dangerous incident almost three years ago, the North Charleston, S.C., District Fire Department decided to form a special hazardous materials response team.

A forklift truck started that incident when it struck a valve on a 6000-gallon tank of dimethylamine at a chemical storage facility in Charleston, opening a 1 1/2 -inch hole in the bottom of the tank.

Dimethylamine is a corrosive flammable liquid with an NFPA 704M system rating of 4 for flammability and a 3 for health. Fire fighters sealed off the area, evacuated personnel from a downwind trucking company, set up a master stream to dilute the chemical and control flammability, and drove a wooden plug into the tank to stop the leak.

Sand trucks from the state highway department were called in, and dikes were constructed to contain runoff. Acetic acid and a carbon-based compound were used to neutralize the chemical.

Planning for the future

The department began planning for future incidents.

“The dimethylamine incident indicated to us that the potential for a major hazardous materials incident involving life exposures is quite real,” noted Assistant Chief Gerald Mishoe recently. “The first-in company had acted immediately to control the vapor problem. Several agencies combined efforts quite effectively to control the situation fairly quickly. However, the experience made us realize there was a great need for more training, more specialized equipment and more coordination with other agencies in handling this type of incident. In September 1979 we organized a volunteer, 16-man hazardous materials response team from the 70 personnel in the department.”

A basic training program in hazardous materials response was initiated. It created a lot of interest among fire fighters who had not volunteered for the special team. Eventually, North Charleston District went to department-wide hazardous materials training. Currently, every fire fighter has been trained in hazardous materials response, and two trucks carry special response gear as well as handle heavy rescue and provide truck company support at fires. The designation “team” refers to the two trucks and the equipment on them, but the team in terms of personnel is the entire department.

Fifteen separate fire departments are required to adequately serve Charleston County. The North Charleston District is a 45-square-mile area roughly in the middle, encompassing the bulk of heavy industrial development within the county. Major railyards and Charleston International Airport are both located within the district, and Interstate Highway 26 runs right down the middle. Nearby is the busy Port of Charleston. Industrial development has brought obvious benefits to Charleston but has contributed to a situation where some industrial areas are located immediately adjacent to residential areas.

One LPG storage farm, for example, contains 45 60,000-gallon storage tanks separated from a major residential neighborhood by a fence. Within Charleston, there is a recognized potential both for industrial fixed-location incidents and for incidents related to any of the five modes of transportation.

Although the North Charleston District Fire Department obtained hazardous materials training from commercial trainers, and had representatives of local companies and the trucking industry give classes, a sizable portion of the training effort involved team members canvassing their response area to take 300 to 400 color slides of specific local situations and facilities.

“We used the slides because we wanted to show personnel that there were not only major hazards in the area, such as those attached to the railyards and the Interstate, but also to show there were potential problems not quite as so obvious: a 500-gallon propane tank behind a local forklift company, a flammable liquid storage area at a sugar bag company, a loading dock at a local warehouse, and stored compressed gases at a welding supply company,” explained Mishoe. “We tried to show potential situations all the way from heavy industry to far less obvious locations such as one of the new miniwarehouses that are being built all over the country. We spent a tremendous amount of time on railroad incidents and different types of railcars because trains come back and forth in front of our station all the time.”

Although acquisition and use of the color slides was initially a training related function, it had obvious benefits for planning as well.

“In our initial training program, we pretty much scoured the area to find our major hazardous materials problem areas,” says Mishoe. “Now, we feel we pretty much have our eyes on those locations where problems are most likely to occur. We hope we will not find a lot of surprises, although I expect we will find some things we may need to do a little differently when we do additional planning.”

Apparatus and equipment

North Charleston District’s Squad 10 truck is a 1948 chassis that previously mounted a generator and was used as a light plant before being converted to a hazardous materials response truck. It is stocked with rubber patches, tapered plugs of various sizes and dimensions, hose clamps, Vice Grips with welded extensions on the jaws, wooden wedges and dowels for sticking in holes, sliced innertubes and assorted hand tools. The truck carries enough gloves, both butyl rubber for use with a variety of chemicals and nitrolatex for strong corrosives, supplied by a local industry to equip all first-response personnel from the department rather than just the personnel attached to the truck.

“Our cascade system is probably the most useful piece of equipment on the truck,” says Captain Hampton Shuping, Jr. “It’s a 1400-cubic-foot, four-cylinder system. We use it all the time. We carry a 55-gallon recovery drum. When we use a sorbent material, we pick it up loaded with chemical, seal it in the recovery drum and either ship it out or dispose of it ourselves depending upon the specific product recovered. We use two varieties of sorbent materials, the pad-type and a clay-like material such as they use in automobile garages. We carry 200 pounds of the clay-like sorbent.

“In 30-gallon drums we carry 90 gallons of AFFF concentrate and 60 gallons of ATC/alcohol-resistant foam, plus two 1-gallon containers of wetting agent,” Shuping adds. “We carry acid-gas suits and proximity suits, as well as four extra airpacks. There is a small hand pump, originally used to pump diesel fuel into our own trucks at prolonged fire operations. We use it to transfer product from a leaking drum to a sound one. It comes in handy when a trailer truck carrying a mixed load of drums has one or two that are defective or holed. It will handle diesel and fuel oils with no problem. We also carry a small siphon hose. We get called to motels quite often where an automobile gas tank is running over into the parking lot. We merely siphon out enough to get the situation under control.

Handling major spills

“We carry 4-foot sections of PVC pipe,” he says. “When responding to overturned tankers or major flammable liquid spills, we first attempt to contain the spill. We throw a section of PVC pipe down in the bottom of a ditch, build a dike over the top of it and temporarily close the pipe with a piece of plywood or whatever is handy. Water being used to divert or flood the spill carries the fuel into the ditch and is caught behind the dike. The mixture settles. The fuel comes to the top of the water. The pipe at the bottom of the dike is opened to let the water underneath flow out, and then the flammable liquid is picked up.”

“Before we used this system,” Mishoe comments, “we had a tanker truck turn over in a heavily populated area where we had to use a tremendous amount of water to divert the fuel into a drain that led to a big ditch where we could dike it. We were concerned with the flammability hazard, so a lot of water was used. The dumped gasoline amounted to 8900 gallons, but we wound up in a 24-hour operation with tankers and pumps picking up 24,000 gallons of gasoline and water. We learned from that experience that we had tripled our spill problem by combining all that water with the gasoline. Now, we use this simple piece of sewer pipe. The technique will work on any product that is insoluble and has a specific gravity of less than 1.”

“Working in acid-gas suits, wearing SCBA, with a relief valve blowing off next to you, it is very difficult to communicate. So we use a 2X4 chalkboard and simply write visual messages back and forth,” notes Shuping. “We carry a number of manuals including NFPA, Bureau of Explosives, the new DOT manual, the OSHA Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards, and some others. We have a combustible gas detector as well as an oxygen-deficiency meter for checking manholes and other confined spaces. If the incident is sizable, say a tanker truck dropping several thousand gallons, then we closely coordinate our efforts with the United States Coast Guard and the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC). With the Coast Guard, DHEC and fire department working together, there has not been anything we’ve come up against that we couldn’t handle.”

Military assistance

“During any radiological incident, we have the capability of calling in a United States Navy team attached to the nuclear submarine base that is located here,” says Mishoe. “We will take a quick reading with the field survey meter (Geiger counter) we have, then bail out if there is a leak and let them handle it. We also use the explosive ordnance disposal team from the naval base if bombs or explosives are involved.

“With regard to acids and alkalis,” he says, “we do not have a pH meter but do use pH papers. In possibly a half-dozen incidents this year, we took quick readings with pH papers that were later checked by meter. The meter readings proved to be very close to the readings we had obtained with the paper, so we feel pH papers are sufficient for our needs. The paper is reasonably quick. You merely dip it into the fluid you are testing, get a reaction on the paper, then match the paper against a chart.

“We had an incident recently where a commodity was running off the highway as if someone had been dumping it as they drove along. A quick test with the pH paper indicated a pH down around 2 ¼ to 3. I followed it out and found a tanker truck with a busted valve had poured 3000 to 4000 gallons of sulfuric acid over a 3 or 4-mile stretch of highway. It was a pretty bad situation. We had to use a vacuum truck to pick up the big puddles, then lay down soda ash to neutralize the remainder.”

Written standard used

For some time now the North Charleston District Fire Department has used a formal, written hazardous materials response standard, much of which was borrowed from the Phoenix, Ariz., Fire Department. It covers objectives, definitions, dispatching, actions of the first-arriving units, size-up, formation of an action plan, control of the hazardous area, use of a hazard zone and an evacuation zone, use of non-fire department personnel, and general guidelines.

“We use a written standard because we found some of our major problems related to response to hazardous materials incidents included exposure of personnel and equipment,” explains Mishoe. “Under the standard, additional units stage around the perimeter and allow the first-in unit to evaluate the situation. The first-in unit then calls in other units as they are needed. The standard has kept us out of trouble.”

The smallest spill

Hazardous materials incidents responded to by North Charleston Dist rict fire fighters range from a 3500-gallon spill of dimethylamine, through hydrochloric and nitric acid spills, down to what may be the smallest hazardous materials spill on record. The local branch of a major, national chain store called one night to say that something was in the air and people couldn’t breathe. Engine company personnel wearing breathing apparatus found two broken 1-ounce bottles of nitric acid in the safe of the jewelry department and the acid was reacting to the metal of the safe.

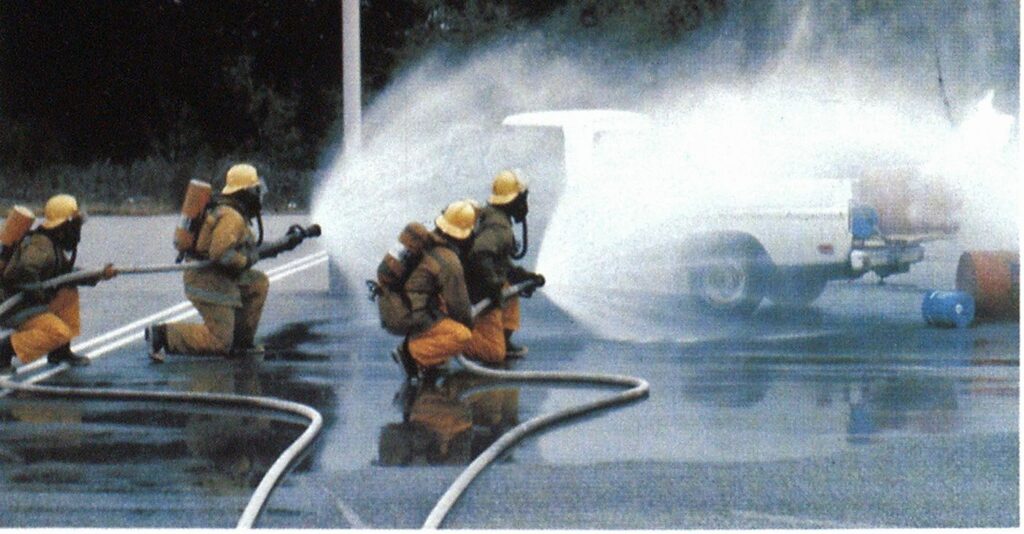

—Photo by the author.

“We respond to a great number of gasoline spills and tend to treat gasoline with a tremendous amount of respect,” says Mishoe. “We believe gasoline is one of the worst hazards we deal with simply because the public has developed a lackadaisical attitude toward it because they see it and use it so much in their everyday lives. People tend to think of hazardous materials as BLEVEs and railroad explosions, but of the 10 incidents a month that we average, most involve small spills.”

Regarding lessons learned, Mishoe reflected recently: “In our particular area, there is the potential for having quite a few different agencies involved in a hazardous materials incident because we have local offices for the Coast Guard, DHEC, Civil Defense and Disaster Preparedness, as well as the naval base, several police, fire and EMS agencies and industry. We found there was a definite need for on-site coordination. If someone does not establish command early in the incident, you may wind up losing control and having six or seven people saying six or seven different things.

Not so fast

“We learned from our dimethylamine incident,” Mishoe says, “that we needed to be a little slower in sizing up and not commit too much equipment or too many personnel prematurely. Overall, we have found that although you have all sorts of reference books and many varied agencies available to supply help, if a fire department will equip itself, have a halfway decent training program and establish a good command procedure, fire department personnel will be able to handle the majority of incidents by themselves.

“We learned there are a lot of people around who have a tremendous amount of expertise,” adds Mishoe. “Once we started getting together on some of these incidents, we learned that we have a tremendous amount of resources right here locally. Everything that is here, everything we use with the exception of a few pieces of equipment, has been here all along. The expertise, the people, and the agencies have been here all along; it was just a matter of putting it all together in a reasonable, usable form.

“If people will begin to prepare for the smaller incidents, learn how to respond well to the smaller incidents,” concludes Mishoe, “they will find the big incidents don’t occur all that often. And when they do, the preparation, experience, and coordination they have achieved in working the small incidents will be helpful to them.”