By Jared Newcombe

Brampton Fire and Emergency Services (BFES) is a progressive, well-equipped, mid-sized Canadian department that provides protection for a city of more than half a million people. Like many other departments, BFES rotates our firefighters through each position on pumpers, squads, and quints each tour of duty. All crew members are trained on and familiar with any engine or truck company assignment, regardless of apparatus designation. Although this practice may automatically diminish situational awareness because of constantly changing roles, training through standard resource deployment (SRD) helps to overcome this.

The first-arriving officer to a house fire assigns tasks based on prioritized strategic objectives and initiates actions that will make the greatest impact.

The first-alarm apparatus dispatched to a reported house fire makes decisions that will affect the outcome of the incident en route and on arrival. Information received through dispatch, preplans, a windshield survey, witnesses, and the 360° walk-around are used to determine the fireground factors that are critical and pose the greatest threat to the tactical priorities of life safety, scene stabilization, and property conservation. The first-arriving officer prioritizes all fireground factors using critical thinking that addresses the dynamics of the fireground: The officer must take in information, process and prioritize it, and then make the best decision.

As we approach the fire, we size up our opponent before engaging. Knowing our opponent gives us an edge in predicting how it will react to actions taken or not taken. Gaining control requires us to think and move faster than our opponent and then employ an overwhelming force. Fire moves swiftly with no regard for life or property. We must be prepared for the unpredictable and be adaptable to challenges that may be presented at any moment. As the number of fires decreases, our opportunities to gain crucible experiences, “defining moments that unleash abilities, force crucial choices, and sharpen focus”1 are quickly fading.

Approaches

A hands-on approach is preferred when working with officers to develop initial incident management skills and create crucible experiences. Two decision-making models are laid out for the officers:

- Gary Klein’s simple match, recognition primed decision making (RPDM)2 enables officers to recognize and differentiate messages using verbal, visual, or other sensory clues and weather. This model is used to identify fireground factors as they relate to training and previous experience.

- Colonel John Boyd’s Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA) Loop3 is used to orient the fireground factors and to triage. Officers can use the OODA loop to determine which fireground factors are critical and prioritize them as they relate to life, scene, and property conservation. The officer can then consider and implement the appropriate course of action.

Once it’s understood that decision making is not linear but a dynamic process of accessing sensory information and determining the best approaches, a game plan (linear list) of ways to approach the fight is necessary. Here, failure to consider and analyze new information can be dangerous. Chaotic situations provide information that is in no predefined order and is forever changing. Orienting information is our on-scene triage; and once initially prioritized, we should think of various tactical approaches. We should not overanalyze but consider and hypothesize which tactic is best suited for the conditions encountered not only on arrival but also when you are ready to implement a potential tactic.

The risk assessment is of utmost importance when determining your course of action, as are resources on hand; the crew’s experience; changing conditions; a full 360° walk-around, or HOT lap; and training. As we practice making decisions in a dynamic environment, we use our minds to evaluate and consider action. This dynamic ongoing process may repeat itself 10 to 15 times or more per minute and is driven by the unpredictable flow of varying information, which we must keep in mind and measure.4

Fighters who can read their opponents are better prepared to establish a plan of attack, adjust their approaches if needed, and gain control. How do you accomplish this?

SRD

In its simplest definition, SRD is a proactive approach to staging required equipment and tools in an operational ready state.

Three phases of training, each with its own focus and goal, build interconnected foundations, forming the basis for effective SRD. With each phase, elements of surprise and stress are introduced. The crew is able to learn and then succeed as a unit. With each phase, there are successes and lessons learned. Each additional phase reinforces the previous phase while adding new elements that require the crew to adjust a previously chosen tactical approach to new variables.

The benefits of SRD training include the following:

- Practiced deployment and purposeful movement.

- Situational awareness of each role and responsibility on the rig.

- Reduction in the amount of detail in the orders from the officer.

- Many tactics may be initiated off the standardized setup.

- Allows for redeployment should tactical priorities change.

- Builds confident adaptable firefighters and strong teams.

Officers who complete this training end up placing a greater emphasis on the 360° walk-around to determine the critical fireground factors. This creates greater situational awareness of the incident details, which enables the officers to better predict and forecast the status of the fire incident on arrival and how it is progressing. Greater awareness allows us to more effectively set/establish our strategic objectives, ensuring that our tactical priorities are met. The decision-making process becomes easier with each drill as officers determine the best use of available resources and prepare assignments, essentially developing and implementing an incident action plan (IAP).

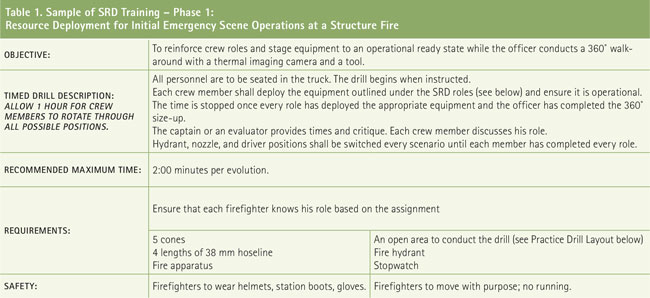

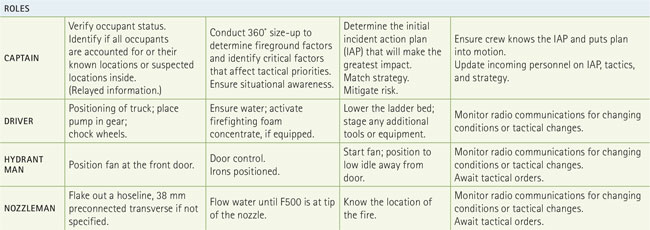

Phase 1

The roles and responsibilities of each crew position on the rig are predefined for the various situations that may be encountered when arriving at a fire incident and being assigned a name that corresponds to an SRD order. The drill consists of members matching the clue cards that show houses in various stages of fire development with the card’s name (the predefined SRD response). The fire situations may include smoke showing, no smoke showing, a garage fire, or a fully involved house fire, for example.

During the drill, the apparatus is staged at a predefined location. The officer is given a clue card (Clue 1), which is opened when the drill begins. The chauffeur drives to the designated training area while the officer provides the clear SRD order that corresponds to the card-for example, a house with no smoke showing and no occupant would be treated as a house fire until proven otherwise. The pump is engaged, and an appropriate size hoseline is flaked out and charged. The ladder rack is lowered; the irons and fan are staged as the officer conducts a thorough size-up. For fires requiring investigation, the exercise reinforces our roles and responsibilities, and we are not left scrambling if the incident is determined to be a fire. Training builds better firefighters and also demonstrates professionalism and purpose.

The officer of the first-arriving apparatus at any fire can implement a simple match decision by identifying fire behavior indicators (FBIs) and matching them to the appropriate SRD. This is a small part of the overall IAP, but it is vital to its success. This allows the officer time to gather and verify information that may not be obvious to the firefighters carrying out the SRD order and helps him to further develop and implement an IAP. Through repeated practice-training-firefighters become very familiar with the time required for each deployment to be successfully carried out. Consider how long it takes for a crew to deploy in relation to the space that must be covered to complete the 360° lap. This enables the officer to make the point that they have enough time to determine occupant status, read the fire, and conduct a risk assessment prior to debriefing with the crew.

Phase 2

This phase highlights more complex decision making and introduces new information at two designated areas that may or may not change the initial tactical approach. In the above example, at the start of the drill, a clue reinforcing phase 1’s deployment for smoke and no smoke showing on arrival was used. In this training phase, clue 2 is presented to the officer conducting the 360° lap on the A side of the designated training area. Clue 2 can include information regarding occupancy, building, smoke, air (flow paths), and heat and flame (B-SAHF)5 indicators in the form of visual and auditory clues. Clue 3 is presented to the officer on the C side. The purpose is to challenge the officers with an evolving situation to provide training in changing the priorities of the strategic objectives and adjusting initial actions that would better serve the tactical priorities. Phase 2 of SRD training introduces obstacles to what is believed to be true on arrival and forces the officer to reconsider the initial SRD. The officer needs to adjust a chosen tactical approach, which requires communication and coordination. For the crew carrying out the initial SRD order, adjusting to new orders necessitates a great deal of situational awareness and practice.

Phase 3

Phase 3 builds on the first two phases of training and focuses on navigating increased radio traffic and allocating resources based on set strategic objectives. As an incident unfolds, communication may be difficult in the first 60 seconds as transmissions may include the results of a windshield survey, a notice of taking command, and updates from the first-in officer followed by repeated on-scene reports from incoming apparatus-they’re all competing for air time.

A second apparatus arrives as well as a chief (by radio simulation only) at the 35- to 40-second mark just as the first-arriving officer is about to adjust his tactical approach and radio update in the form of a CAN (conditions, actions, needs) report. This disruption affects the officer’s ability to communicate, and yet the incident is moving forward in addition to the change experienced in Phase 2. The clock is ticking; decisions have to be made based on a greater degree of situational awareness. Redeployment orders and assignments for incoming apparatus have to be developed. When the officer has control of the fireground radio channel, he may then implement the decisions made, laying the foundation for a more complete IAP.

When under stress, he may not relay messages clearly. This is addressed in every phase of training. Phase 1 has the officer giving the initial SRD order to the crew based on initial information. Phase 2 has the officer dealing with new information that may affect new orders that need to be communicated to the crew. Phase 3 has the officer facing increased radio traffic, additional apparatus, and a senior officer; and still the fire marches on. Effective communications is a skill that is highlighted and repeated. Practice benefits everyone.

Each phase of SRD training presents a crucible experience to both the officer and the crew. Phase 1 instills roles and responsibilities for any firefighter, from any seat of the truck, while the captain learns the importance of carefully conducting a 360° walk-around. Phase 2 trains firefighters to be adaptable to a changing scene and not to become task fixated. The officer learns/practices collecting and processing new information, challenging the officer to reprioritize the tactical approach and set new strategic objectives. Additional radio traffic in Phase 3 creates a third crucible experience: The officer learns/practices adjusting tactical approaches and providing assignments to incoming apparatus while competing for air time as the firefighters adapt to a new task.

The crews have realized through repeated drilling and position rotation that SRD training has improved the quality of work and situational awareness. No longer fixated on tasks, SRD builds officers and firefighters who are more adaptable and better equipped to respond and react to changing fire conditions. Dr. Richard B. Gasaway’s B.S. (Brain Science) has assisted immensely in identifying situational awareness barriers and bringing them to light in a positive and constructive manner when conducting our SRD drills. “Situational Awareness Matters” is a Web site dedicated to helping us understand human factors, reduce the impact of situational awareness barriers, and improve decision making under stress. The repeated exposure to the drills, which were initially challenging, made them very easy over time, and they were executed by our crews as seasoned Formula One pit crews.

The biggest lesson to be learned from SRD training is teaching officers how to think as opposed to telling them what to think. There is not one golden tactic to remedy a problem but a series of best practices to choose from that allow for adaptability as a situation evolves.

SRD training is done as a crew; it’s building a team. SRD training can be conducted anytime and anywhere to build situational awareness, improve decision making, and promote adaptability. It is as much about the officer as it is the firefighter. SRD training develops the adaptability and decision-making prowess of the officer while reinforcing the various roles and responsibilities of the first-arriving crew, regardless of apparatus designation. SRD sets the stage for the first-arriving crew to make the greatest possible impact.

References

1. Bennis, Warren G, and Robert J Thomas. Geeks & Geezers: How Era, Values, and Defining Moments Shape Leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2002, 16.

2. Klein, Gary and David Klinger. “Naturalistic Decision Making.” Human Systems IAC GATEWAY 11, no. 3, 16-19. www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/decision/nat-dm.pdf.

3. Brehmer, Berndt. “The Dynamic OODA Loop: Amalgamating Boyd’s OODA Loop and the Cybernetic Approach to Command and Control.” Contribution to the 10th International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, 2005.

4. Dettmer, H William. “Destruction and Creation: Analysis and Synthesis.” Goal System International. http://www.goalsys.com/systemsthinking/documents/Part-3-DestructionandCreation.pdf, 2006.

5. Hartin, Ed. “Reading the Fire: B-SAHF.” (Presentation at the Congreso Internacional Fuego Y Rescato, Valdivia, Chile, Jan 2010).

JARED NEWCOMBE is a captain and a 23-year veteran of the Brampton Fire and Emergency Services in Ontario, Canada. He is also a live fire instructor.

Filling the New Officer’s Toolbox

A Day in the Life of a Company Officer

Training Officer’s Toolbox: Influence

Fire Engineering Archives