Don’t Let the Rescue Be You

features

FIRE REPORT

Photo by Susan winters

The all too common and naive belief that “it can’t happen to me” often accounts for many line-of-duty injuries suffered in the fire service.

Even the most experienced and seasoned firefighter can become a statistic if he chooses to ignore warning signs and jeopardize his safety.

I know. Last May 26, while operating at a three-alarm structure fire, I was the victim of a collapse.

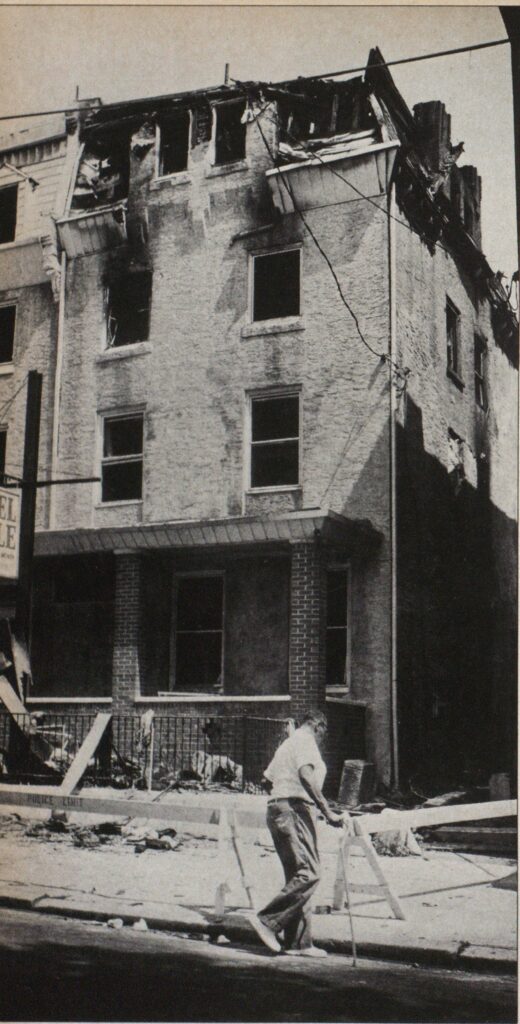

Four engines and two ladder trucks responded to a 4:34 A M. alarm reporting a fire at the New Hotel Carlyle, a four-story, 80 X 100-foot building of ordinary construction which is located in Francisville, the poverty-stricken ghetto in North Philadelphia, PA. Years of alterations rendered the first floor of this transient hotel a virtual labyrinth of crisscrossing halls and dead-end corridors.

The second, third, and fourth floors contained many small cubicle-type, single room occupancies, and some second-floor windows were sealed with cinderblocks.

It was a blessing that most of the rooms did not have doors, only curtains to suggest privacy. While this fact threatened a more rapid horizontal fire extension, it saved search time ordinarily lost in forcible entry.

Considering the time of the fire, life safety and accountability were of primary concern. Therefore, the strategy was to begin an aggressive interior attack, with ladder companies immediately committed to search and coordinated venting operations, and engine companies assigned to place water between the fire and the most Severe exposure (life) and to keep the fire from extending to uninvolved portions of the building.

The protection of external exposures too was considered in the strategy. Exposure 1, the buildings directly across the street, and Exposure 2, a private dwelling separated from the fire building by an open space, presented no immediate problems to fire forces. Exposure 3, three-story private dwellings 20 feet to the rear of the hotel, was of more concern. The most severe external exposure, seven feet to the right of the Hotel Carlyle, was the Harris House Hotel, 40 X 70 feet and three stories high (see map on page 48).

Heavy fire was showing from the front of the Hotel Carlyle on the first floor and had already extended to the public hallway. Smoke was thick in the street. An emergency medical service unit (EMS) and a deputy chief were dispatched to the scene.

Addressing the life hazard before opening the roof, the first-arriving ladder company positioned its apparatus in front of the fire building and raised its aerial to the fourth floor for search operations. Other members conducted a primary search of the first floor.

Photo by George Bolechowski

Photo by George Boiechowski

The second-arriving ladder company positioned themselves in the rear of the fire building. After learning the extent of and risk presented by the fire on the first floor, portable ladders were raised on Side 4 of the fire building to gain access to and conduct a primary search of the second and third floors.

Despite efficient firefighting efforts, the fire had already gained considerable headway, quickly spreading to the open interior stairway and rapidly extending vertically to the top floor.

A second alarm was transmitted, bringing five engines, a ladder, and two battalion chiefs. Shortly after this, a third alarm was transmitted, bringing four engines, a ladder truck, and another battalion chief.

My ladder company was ordered to make a search of the rear section of the hotel from Side 3 of the fire building.

While searching one of the rooms on the second floor, I spotted the reflection of a flame on the window of the adjacent Harris House Hotel. Peering out, I saw that the fire had already extended to the floors above me, but couldn’t determine the exact extent due to the heavy smoke.

I climbed out onto the roof of a first-floor extension. I saw that the fire had traveled horizontally along the third floor with flames issuing from five of the seven windows.

There were enough warning signs to indicate a partial collapse. The building construction alone increased the collapse potential. Also, two floors were heavily involved in a fire that had been traveling within the structure for 15 minutes—these were sure warnings that additional collapse indicators needed to be sought out.

Yet, we refused to retreat. After informing the sector commander of the current conditions in the rear, I started to reenter the hotel.

Part of the support for the main roof broke loose. Attached to the support was the wooden cornice. Both support and cornice fell straight down. I was struck on top of the helmet and across the upper back.

There were many rescues and removals made during the Hotel Carlyle incident. But one could have been prevented.

Thanks to the efficient and coordinated efforts of firefighting and EMS personnel, particularly Phil Cameron and Chris Myers, the extent of my injuries was minimized and I sustained a broken neck.

The Hotel Carlyle suffered major damage on the third and fourth floors, and one of the fourth floor occupants succumbed to smoke inhalation. The Harris House sustained minor damage from radiant heat.

CRITIQUE

Traditionally, fire departments hold a critique on a fire of this magnitude. But, could more be done? I believe so. Therefore, I felt compelled to combine the lessons learned and reinforced with a practical memory device. A mnemonic that can be used by the effective ladder company officer at any hotel fire whenever the order is given for search and rescue responsibilities is “rescue”:

R is for REGISTRATION BOOK. Getting this bit of information along with a list of handicapped occupants, the master key for all rooms, and the building manager are major duties of a ladder officer. All of these components will be a great aid in developing the overall strategy and insuring that accountability is fast and accurate.

E is for EVACUATION. The importance of establishing an additional independent and safe means of egress cannot be overlooked. If an alternate exit is not provided by the building’s construction features, provide one via aerial, tower, and/or portable ladders. It is always more difficult to attempt firefighting and evacuation from the same stairway.

S is for STAFFING. A hotel fire will require plenty of manpower. There is no room for freelancing. All units must be deployed with specific assignments and attainable goals. The ladder company officers must be able to assist the fireground commander in assignments, tactics, and communications.

C is for COMMUNICATION. This is the primary element of a team operation. Messages must be short, concise, clear, and accurate. Ladder company officers must relay vital information back to the command post so that the fireground commander can make sound, objective decisions.

U is for YOU. Personal safety is your responsibility. When any firefighter is unexpectedly injured, conditions on the fireground change dramatically. Often it can lead to general chaos which can have a snowballing effect. Therefore, it is essential that all firefighters adhere to every safety tip all the time, not just when it is convenient. They must act as their own safety officer.

E is for EVALUATION. Continual monitoring, reassessing conditions, and adjusting tactics are mandatory for a successful operation. The ladder company officer is the key. During the initial stage of any operation, the preincident plans and maps (water and building) must be accessible to the command post. Extra units are often needed in the rear for forcible entry (due to additional security measures such as bars, locks, and metal grates), raising portable ladders (because of confined areas, utility wires, and uneven terrain), or to protect the exposures. Later, if there is the potential for collapse, the ladder company officer must quickly size up the area of his responsibility to insure its stability.

In conclusion, the ladder company officer can be viewed as the critical link between the fire scene and the fireground commander. Between success and failure. Next time you are given the responsibility to be the officer in charge of ladder company operations, plan en route, think on the fireground, and be prepared to confront the unexpected. Then the odds are better that the next rescue won’t be you.