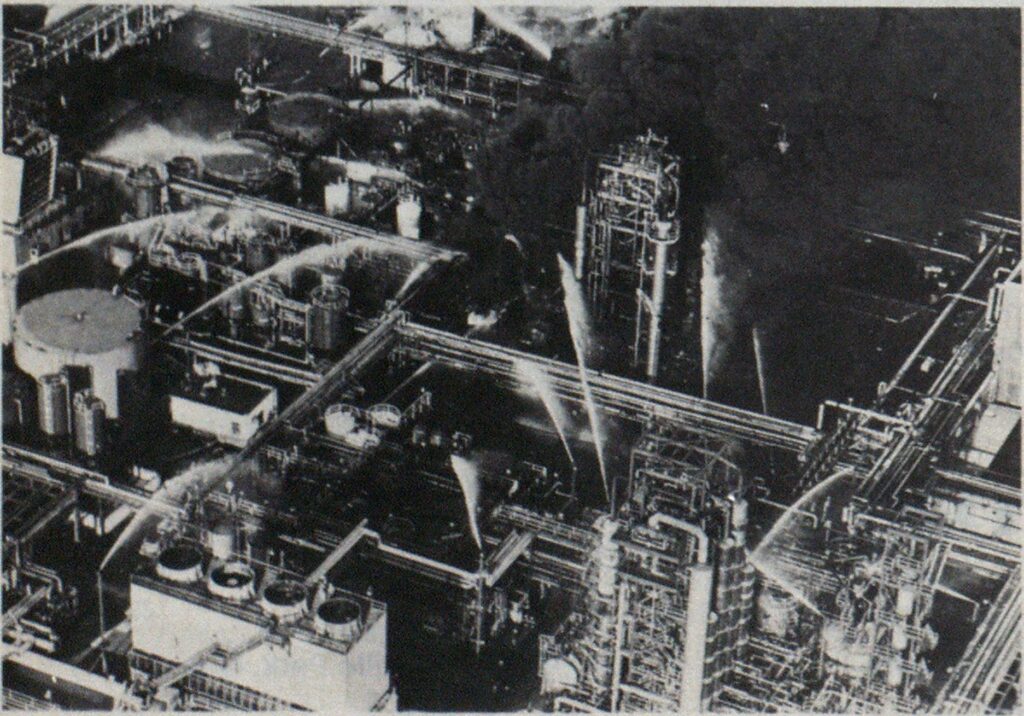

Another Explosion, Another Fire At Allied Chemical Plant in Philly

features

Without warning there was a tremendous explosion that witnesses compared to a giant sun rising in the sky. Concussion rocked the area, ripping out the windows in the nearby Longfellow School and along the street. Fortunately there were no children in the school because classes had been dismissed some 20 minutes earlier. Homes were rocked. Debris rained down on a highway 160 yards away. Passing motorists reported a temperature rise in their cars of 30 to 45 degrees.

It was at the Allied Fibers and Plastics Company in Philadelphia—again. This explosion happened at 3:05 p.m. last March 9, a Tuesday, in the company’s cumene plant. An almost identical explosion occurred on March 8, a Tuesday, at 3:55 p.m. in the same location of the same plant in 1955. Both touched off raging fires.

“Despite the dangers under which the fire fighters operated,” said an April 1955 story in Fire Engineering about that fire, “only four firemen were injured.” Four fire fighters were also injured at the most recent incident.

But Captain R. Wiseman of Engine 33 knew it was a new and unpredictable situation they would be facing this time when he gave the first radio report: “We have an explosion at Allied Chemical. Strike out a box. There is a giant column of smoke. We can see fire in it. My God!”

3 1/2-inch hose

Engine 33 rolled into the 45-acre plant and connected to a yard hydrant 200 feet from the fire, leading off with 3 1/2-inch hose to a deluge gun on the west side of the fire.

Based on Engine 33’s initial report, fire alarm dispatched Hazardous Materials Task Force 3 on the box alarm, which meant that Engine 7, Ladder 10, Rescue 2 and Chemical 3 were responding as a unit.

This battle had been planned in advance. Philadelphia units had been trained by plant personnel through regular training and drilling sessions. A response plan was kept up to date. Carried with the haz-mat task force was a copy of the plant emergency book.

Plant crews

The plant itself was ready, too. Under the direction of W.K. Hudson, the safety supervisor, and the plant’s fire chief, George Stutz, plant personnel had gone into action prior to the arrival of the city fire department.

Under Stutz were two assistant chiefs, four hose company teams of eight men, each under a captain, and a rescue unit of 15 men trained as EMTs. A traffic unit designed to control response activities within the yard went into operation, along with a security group to see that no one other than fire department or plant personnel entered the yard.

Plant crews responded with two chemical pumpers, one a 1000-gpm unit to produce universal foam, and the other a 750-gpm apparatus equipped to make alcohol foam.

The plant water supply was excellent, featuring over 50 yard hydrants and their own pumping system with a 1500-gpm steam pump, a 1500-gpm electric pump and two 2500-gpm diesel pumps. They had two reservoir tanks containing over a million gallons of water. A static pressure of 125 psi was maintained on the yard system.

The yard system was immediately activated. Fifteen high-level monitors discharging 500 gpm each were started up and directed at the fire and exposed tanks. The fire was centered in six tanks. And at this moment it was raging out of control.

Fast extra alarms

Philadelphia Battalion Chief John Jackson did not wait to get to the fire before summoning help. The looming smoke was so great ahead that it appeared to be much closer than it was. Jackson picked up his radio and ordered a second alarm at 3:07 p.m. A fourth alarm was ordered within another three minutes.

F’ire Commissioner Joseph Rizzo headed for the Delaware Expressway (1-95), but as he approached an entrance he saw that traffic was already backing up on that route. He broadcast a warning to all responding units that 1-95 was closed to them, and to respond via Aramingo Ave.

At the same, time, he directed Battalion Chief James Leonard to set up a staging area for arriving apparatus and commit them to service in areas as needed. Bat talion Chief John Hunter, the water liaison officer on the second alarm, and Engine 70, the water supply company, assisted in directing companies for service.

—Wide World Photos

On the first alarm, Engine 52 connected to the intake of the plant water system on the Bridge St. side, and Leonard designated another company to replace Engine 7, which had responded as a chemical task force, on the Wakeling St. side.

Cumene is an irritant

The blast and fire had occurred in two batteries of tanks containing over 100,000 gallons of cumene hydroperoxide which chemical advisers stated was an irritant but was not toxic. The chemical is a byproduct of phenol, a flammable substance used in the manufacture of man-made fibers, glue, lubrication oil, weed killers and other items. Three tanks were ruptured. A tank containing thousands of gallons of fuel oil was also involved in the fire.

Flames leaped high into the massive cloud of dark smoke which towered over I-95, forcing the police to shut down the interstate and Aramingo Ave., creating massive traffic jams that hampered apparatus trying to reach the scene.

First-alarm engine companies all stretched in with 3 1/2-inch lines to deluge guns, taking up preassigned positions. The chemical task force set up to discharge foam on the fire.

Units arriving on greater alarms were placed in service as quickly as possible, consistent with an orderly manner. Rizzo was on the foreground within 10 minutes and received reports from the officer in charge, Deputy Chief John Grugan. He then proceeded to seek out the chemical advisers and learn from them what was involved in the fire and what would be considered the best course of action to take.

Exposures protected

The paramount job was to protect the exposures. Officials were concerned about the large tank of fuel oil. The top of this tank was swelling and threatening to blow apart. Three tanks of acetone were exposed to the fire, as were 20 tanks containing various products.

Rizzo ordered the transmission of the fifth alarm at 3:28. Just to the left of the main body of fire was a tank of oxidizer. It was reported that the internal temperature of the tank was estimated to be 85 degrees. If it went to 125 degrees, it would explode. Deluge guns were immediately brought to bear on this tank. It was impossible to accurately keep check on the temperature because the control line had been knocked out by the explosion.

After checking with Grugan at the north side of the fire, Rizzo ordered the transmission of the sixth alarm at 3:47, with orders for companies to report to Grugan.

There were now 25 engine companies, five ladder companies, two rescue units and six chief officers. Approximately 160 Philadelphia fire fighters and 150 plant personnel were on hand at the fire.

—Philadelphia F.D. official photos.

Keeping low

Rizzo made no effort to use the ladder trucks or elevating platforms. He felt that to put men in an elevated position would have needlessly exposed them to danger. In the event of another explosion, there was no way they could have escaped. In any event, the maze of overhead pipes rendered the ladder trucks almost useless. The plant had high built-in deluge guns that were directing water down on the tanks. Later, deluge guns were lashed to lift towers. Philadelphia Chemical Units 1 and 2 were summoned to the fireground to bring additional foam. Crews of ladder companies were used to unload foam as well as 2000 gallons of foam supplied by Rohm & Haas as part of a mutual aid plan between plants.

But to have used foam to extinguish the main fire in the cumene tanks would have necessitated shutting down the water streams used to cool the exposed tanks, and this maneuver was considered too dangerous.

Employee shuts valve

An employee of the plant volunteered to shut off an open valve that allowed highly flammable product to flow through pipelines connecting burning tanks to 20 large storage tanks containing thousands of gallons more of cumene, phenol and acetone. The area he entered was surrounded by flames and dense, noxious smoke. The area was within a dike filled with several feet of water and chemicals.

“We thought we would have to send him in a rowboat,” said Rizzo, but the volunteer, covered in protective clothing, waded into the area. He turned off the valve while fire fighters held on to a lifeline attached to him, and he returned safely. Ken Mills, Allied vice president for employee relations, declined to identify the employee.

—Philadelphia F.D. offical photos.

“We don’t want to single out any one person,” Mills said. “We feel all our employees and the Philadelphia fire fighters were heroes in this situation.”

Three hours after the explosion, the fire appeared to be contained but far from under control. Engine 72’s articulating boom and foam units were in the vicinity of the fire, but fire fighters were kept out of the area as much as possible. The wisdom of this action was borne out when explosions ripped the air at 7:04 and 7:11. They caused no injuries.

All three department light wagons were ordered to the scene shortly after 7 to provide illumination on the fireground.

Allied Vice President Jack Owens was in Richmond, Va., when he received word of the explosion and fire. He chartered a plane and flew to Philadelphia. He called a conference of fire and plant officials, asked them their priorities, and then proceeded to see that their orders were carried out as expeditiously as possible. The conference was a model of cooperation between industry and fire department personnel.

Shortly after 8:00 p.m., Rizzo ordered all ladder trucks on the fireground returned to their stations, but he did not put the fire under control. His reasoning was that the trucks themselves were not being used, and their crews could return to normal duties. If a need arose, they could have been recalled to the plant. As it turned out, there was no need for them to return.

Environmental effects

The dense cloud of black smoke drifting over New Jersey forced some residents to remain indoors. Some persons who ventured outside had to seek hospital treatment for eye irritations, but officials said tests showed neither the fumes nor the chemicals that entered the Frankford Creek and flowed into the Delaware River posed serious health hazards.

The United States Coast Guard used absorption booms to try to contain the chemical spill, and two vacuum trucks removed it from the creek. However, Philadelphia Water Commissioner William Marazzo said the spill posed no threat to the city’s water supply. A spokesman for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in Philadelphia stated air sample tests showed no danger to nearby residents.

Safety Director Ken Hudson explained that the explosion occurred near the time of a shift change, so there were not too many people in the immediate vicinity. Allied reported 17 first-aid cases, and one employee suffered a serious back injury when he was knocked from a catwalk by the explosion. The plant maintains its own dispensary and ambulance, with a registered nurse on duty at all times.

Fire cause

The cause of the fire is under investigation by both the Philadelphia fire marshal’s office and plant officials. Unofficially, plant personnel stated the fire might have been caused by a faulty instrument that allowed a chemical tank to overflow.

The overflowing chemicals then might have come into contact with one of a number of hot steam pipes, igniting the blast that caused an estimated $5 million damage and left the area a mass of tangled wreckage.

Rizzo declared the fire under control at 12:18 a.m. on Wednesday, Mar. 10. Philadelphia fire fighters had stretched in over 18,000 feet of 3 1/2-inch line, 1000 feet of 5-inch, and smaller amounts of 2 1/2 and 1 3/4-inch used to extinguish fire in buildings.

They had used 23 deluge guns, two lines to feed the plant system, and lines to foam pumpers. Eleven of the yard hydrants were used, the balance of hose lines being stretched in from outside the plant. Not counting the fireground detail which remained on the scene after 8 a.m. Wednesday, the Philadelphia Fire Department had logged over 1600 man-hours at the fire. The longest service of any engine company was 19 hours and 31 minutes.

Fire-industry cooperation

This fire illustrates the wisdom of a cooperative, coordinated effort on the part of both the plant management and the fire department. Close and frequent consultation between safety and security personnel of the plant and the fire commissioner paid off.

The fact that mutual aid was available from chemical companies was a large plus.

The plant emergency coordinator was in communication with the fire department through a radio tuned to the F-4, or fireground channel of the fire department.

One outgrowth of the fire was a meeting between city officials and the area residents. The nearby Bridesburg section is relatively isolated by natural barriers such as the plants in question and the Frankford Creek. With many streets closed, there was really only one prime street leading out of the area. As a result of the meeting, city officials agreed to work on an evacuation plan, geared particularly to the removal and assistance to elderly residents. A committee has been formed and plans are being drawn up for evacuation in the event of future emergencies in the area.

The plan book carried by the department chemical company gave inside knowledge about water supplies, personnel and hazards. In any sustained operation such as this, these plans were an advantage to the fire department.

Once again, training paid off.