MED-8 Solves Common Problems In Development of Paramedic Service

features

Staff Correspondent

One of the nation’s newest paramedic units, serving 72,000 residents in seven suburban communities with populations ranging from 1600 to 16,000 each, recently went in service in Glendale, Wis.

Designated MED-8, this rig carries thousands of emergency treatment items in 300 separate categories for use by its highly trained crew.

How were the crew members selected? How was the vehicle equipped? What kind of training program was used? Answering these questions provides a representative look at the state of today’s paramedic operations in the United States.

Although locally owned through a public subscription fund, the MED-8 vehicle is part of a countywide system, as yet incomplete (see Fire Engineering, November 1978). Equipment, training, and procedures are standardized throughout the area. Local options exist, but much of the program structure rests on a combination of state law, federal specifications and the standards of national medical groups.

The basic nature of the vehicle itself is fixed almost entirely by federal specification KKK-A-1822, first issued in 1974 and revised several times. Its 40 pages, describing lighting, dimensions, insignia, control switches, etc., have resulted in today’s standard modular ambulance construction that is seen everywhere.

Equipment carried

Of greater concern than the standardized details of vehicle design are the equipment and personnel. A general basis for the items carried is the “Essential Equipment for Ambulances” list issued by the Committee on Trauma of the American College of Surgeons. First drafted in 1961 and revised in 1970 and 1975, this list was largely incorporated into KKK-A-1822. It was originally termed a “minimal equipment list.” That word minimal was changed in 1970 to essential to avoid giving the impression that this was the very least an operator might get by with.

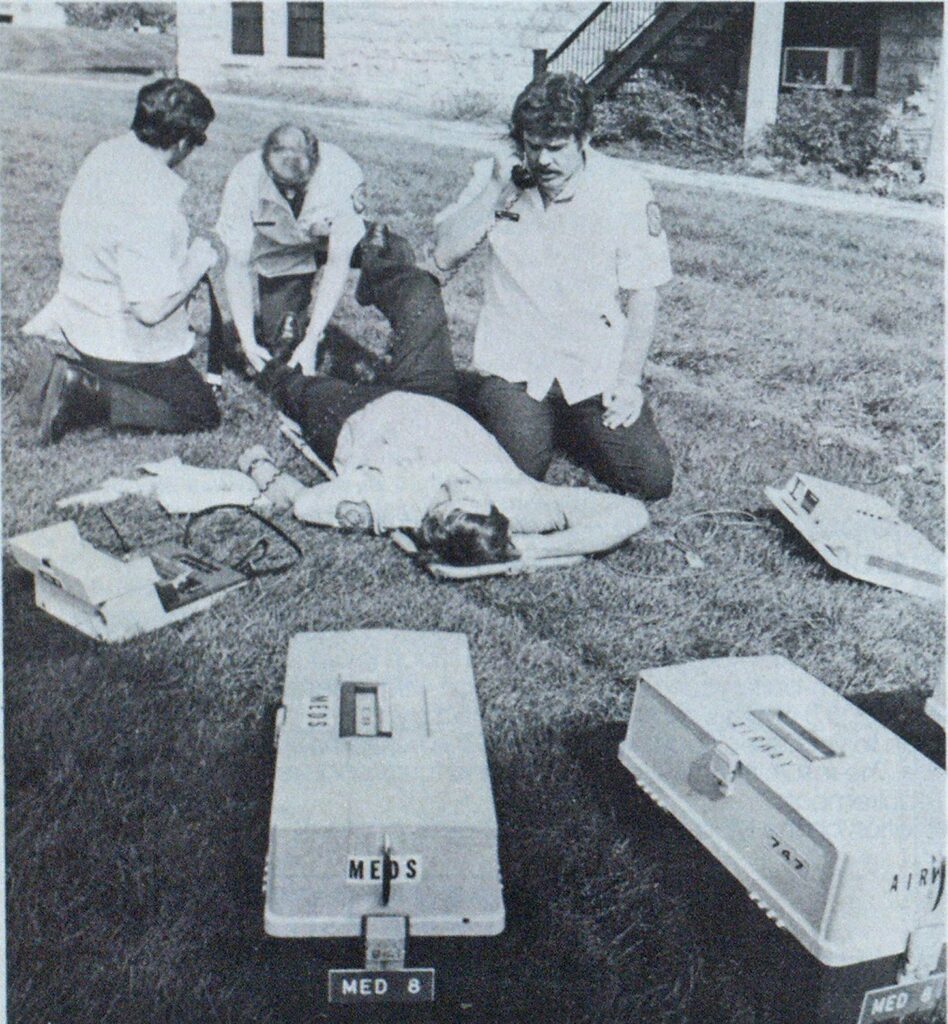

Photo by Bill Mokros

However, much of the inventory of equipment and supplies will depend on the particular local program. The ACS list calls for IV solutions, syringes and needles, and a cardioscope—items whose sizes, types, and quantities can vary widely. What is needed in semirural areas such as Whatcom County, Wash., with long response times and distant hospitals, may not be needed in Seattle.

The principal life-threatening situations MED-8 was intended to deal with are chest pain, diabetic complications, trouble breathing, heart attack, overdose, obstetric, unconsciousness, hemorrhage, and severe trauma—auto collision, gunshot or stabbing wound, industrial accident, etc.

At least some symptoms of many other conditions can be treated also.

Equipment carried on the vehicle falls into these three categories: cardiac/ respirator, trauma and miscellaneous (see accompanying lists).

Three types of kits

Among the most important pieces of gear, usually carried to the patient when the crew arrives at the scene of an emergency, are three kits—identical Plano tackle boxes containing three folding drawers. In the med kit are two concentrations of epinephrine, lidocaine, atropine, ammonia capsules, sodium bicarbonate, dextrose, dopamine, isuprel, lasix, narcan, lactated Ringers and D5W solutions, two blood-drawing sets, and various tools for administering these drugs, including more than 40 assorted needles, syringes, and injectors.

In the airway kit are five oral plus four nasal airways, tongue blades and venous tourniquests, two laryngoscopes, NG tube, nasal cannula, suction catheter, 17 more needles and syringes, and several miscellaneous items.

In the third trauma kit are cervical collars, half a dozen rolls of Kling, four airways, bandages, irrigating solution, four arm and leg splints, tongue blades, eye pads, and another seven needles and syringes.

All three kits contain D5W solution; the med and trauma kits each have 1000 cc Ringers also. Overlap of these and other items among the different kits allows treatment of unexpected complications even though all the kits may not have been brought to the patient.

Drugs and travel distance

How are the drugs selected? Replied Judy Larsen, R.N., chief paramedic instructor, “What we carry are those drugs that are potentially life-saving in our urban context. We’re working 10 to 20 minutes from the hospital. So we don’t carry insulin, for instance. The diabetic can be taken to the hospital soon enough without it, but in hypoglycemia, he might die first. Therefore, we do carry dextrose.”

She also stressed that for consistence within the EMS system, the program’s medical advisers have selected one primary approach to treating each problem.

“The physician could prescribe many different medications,” she pointed out. “We have to limit his choice to what the paramedics are trained to use. We make sure the doctors who are advising the paramedics on a case by radio realize that although there may be 10 ways to treat the condition, we are going to use this particular one—don’t expect some other procedure to be followed.”

MED-8’s inventory furnishes several examples of local equipment differences which occur from one area to another. The Glendale unit carries some rescue tools that other paramedic units in the county do not because, unlike them, it may not be accompanied by a fire unit with such items.

Similarly, in nearby Milwaukee, a specially equipped monitoring squad responds on major fire alarms to check absorption of carbon monoxide in the blood of fire fighters exposed to smoke. Paramedic units there don’t need such monitoring equipment. But the suburbs have no such squads, so MED-8 carries its own CO gear.

Another item needed in Glendale, which would be wasted in Miami, for example, is a shovel to clear a winter path through snow for patient transport. It might otherwise be impossible to get a patient out of his home.

Most have fire experience

Whatever the equipment, it can function only through trained personnel. Of the three-shift MED-8 crew of 12, eight had varying fire fighter backgrounds before being hired by Glendale for paramedic service. The local fire department is so small (20 paid men at the time) that most of the paramedics had to be new to the community. One of these is the county’s only woman paramedic, Erika Rehm, who besides Army medical training had completed several years of medical school plus operating room experience.

Before the start of training for MED-8, each candidate was interviewed for half an hour by the paramedic program director, Dr. Joseph Darin, head of emergency medical services for Milwaukee County.

Asked what he looks for in prospective paramedics, Darin replied in one word: “Commitment. Are they dedicated to bettering themselves? Do they pursue interests and hobbies? Whatever it is that they do, are they doers?”

Along similar lines, Ms. Larsen described the necessary attributes as: “Judgment, maturity, common sense. This isn’t always a function of age, but the older trainees often show more of it. This even outweighs the handicap some of them have in being out of school so long they need to relearn study habits.

“You see, the paramedic can refuse any order he is given by the doctor back at the hospital. He better have a good reason for it, but he must have that choice because he is there with the patient. The doctor isn’t. This is a big responsibility, and our watchword is you have to he safe. Don’t ever make the patient worse by your direct actions. He already has problems; don’t add to them.”

Three Categories of Equipment on MED-8

Cardiac/Respiratory

Airway kit plus:

2 Magill forceps

Adult and pediatric endotracheal (ET) tubes

Bag mask; adult and pediatric facepieces

Infant bag mask

Oxygen masks

Portable oxygen set

Oxygen cylinders, 3 sizes

Cardioscope/defibrillator with cables, spare batteries, and charger

2 boxes EKG paper

1 box EKG electrodes and electrode jelly

2 venous tourniquets

Laryngoscope with assorted straight and curved blades

Battery-powered suction unit with charger

Intravenous (IV) and intercardiac (IC) injectors, drip and extension units, syringes and needles—about 100 separate items

26 bags Ringers and D5W solutions

Trauma

Trauma kit plus:

Associated splints—7 items

Pediatric traction splint

3 short and long spine boards

2 sterile towels plus assorted linens

Suture removal kit

4 pairs surgeon’s gloves

Crash shears

Bandage scissors

Various widths of Kling and Kerlix stretchable gauze—10 items

Roll of aluminum foil (non-stick dressing; also to keep premature infants warm

Eye pads

Dressings

3 sizes cervical collars

Adhesive and Ace bandages

Irrigation tray

Trauma mat for transferring patient from cot to hospital bed

6 18 x 22-inch trauma pak dressings

4 multi-trauma dressings

4 cold pacs

sandbags to immobilize limbs

Miscellaneous

Med kit plus:

Alcohol, disinfectants, sodium chloride, hydrogen peroxide, Neosporin ointment

Examination gloves

E-Z scrub

Spinal tap needles

Needle cutter

2 emesis basins

Portable urinal

Blood pressure cuffs and bulb

Nasal cannula

Assorted suction catheters

Salem sump tube (nasogastric or NG)

25 packs lubricating jelly

Blood sampling sets—vacu-sealed test tubes, holders, etc.—26 items

12 tongue blades

3 bite sticks

Arm boards

5 blankets

MAST (inflatable anti-shock trousers)

Cot plus 2 stretchers

Wrist and belt restraints

2 sets demand breathing apparatus

Poison antidote kit

2 OB kits

“Physician’s Desk Reference” book— identifies by pictures and descriptions any pills or capsules patient may have been using

Thermometer

Radiological monitor

6 razors

EKG and voice portable radio equipment

CO monitor with tubes, bags and test tank

Mortuary pack

Hot stick and pike pole

Shovel

Tool box

5-lb. dry chemical extinguisher

Four on each duty tour

How many paramedics are needed on a shift? State law usually sets a minimum. Although some units operate successfully with two, three seems more common.

“The extra men make the job a lot easier,” as one doctor put it.

MED-8 has four assigned to each 24-hour tour of duty. However, there are no relief personnel, so vacations and illnesses commonly result in a crew of three.

The amount and variety of legislation—federal and state—dealing with EMS generally, and paramedics in particular, is far too extensive to even summarize here. As yet, however, no single federal standard defines exactly what a paramedic must learn.

Instruction is based on what services the law allows a paramedic to perform. That varies from state to state. Illinois Senate Bill 1571, passed in 1972, differs from Minnesota’s 1975 law HF 1441. Training programs range from less than 200 hours to more than 1000.

Comparing programs on the basis of curriculum hours can be misleading. For one thing, refresher training is essential for the paramedic to retain his skills, as well as to keep up with developments. How much time that takes per month or per year can vary greatly from one community to another.

A second variable is the amount of professional medical supervision on the job. This depends on the wording of the law and on the doctor in charge of the program. The third variable is the division of training hours among classroom, clinic and field. And finally, an hour’s training time can sometimes be 60 minutes of direct instruction, perhaps a period of observing, or waiting for a run.

Basic course ingredients

For all those reasons, it’s unwise to assume that a paramedic with 800 hours of formal t raining is necessarily going to do a poorer job than one with 700 hours. Whatever the time spent and the subjects covered, the specific teaching methods must be worked out by each jurisdiction, based on the resources available. It’s generally agreed that these ingredients are needed:

- Classroom work—the textbook understanding of conditions and their treatments.

- Clinical observation—firsthand witnessing of medical and surgical procedures.

- Examinations to verify the trainee’s grasp of what he has learned—written and oral.

- Practical demonstrations of his knowledge by the trainee to show that he can actually carry out the procedures he has learned.

Photo by Bill Mokros

Glendale curriculum

For Glendale’s MED-8, the curriculum was first of all based on Wisconsin law, administered by the State Department of Health and Social Services. Required are at least 75 hours of instruction, a certain course content and a detailed licensing exam. Here’s what MED-8’s crew went through:

Phase I—successful completion of the standard 81-hour EMT-1 course followed by state licensure.

Phase II—13 weeks of classroom/ clinical rotation. The 12 trainees, on a 40-hour duty week completely detached from the fire service, were split into two groups. One group reported for duty at 7 a.m. Trainees were variously assigned to the Milwaukee County Medical Complex (operating-recovery rooms, labor-delivery suite, outpatient, emergency, and pathology-autopsies), Milwaukee Children’s Hospital or Columbia Hospital.

After lunch, this group went into the classroom from 1 to 4 p.m. They were joined there by the second group which after 4 p.m. went on into their hospital assignments until 10 p.m.

Operating room duty

“During an operating room assignment, for instance,” explained Ms. Larsen, “they would be put with an anesthesiologist to visit the patient before surgery. The trainee can start the pre-op IV. In the operating room, the student may put down an ET tube and monitor vital signs during the first part of the operation. Since County is a teaching hospital, the doctors here are quite supportive—great at showing the trainees things to look for later in the field.”

In the hospital work, there are no more than three students per instructor.

During three of the four-hour clinical rotation sessions, trainees ride with a working paramedic unit on each response as observers only.

Everybody is together for classroom work because, Ms. Larsen pointed out, the doctors would rather not lecture to a small group of only two or three. Scheduling becomes extremely difficult to make sure everyone in a class of nine to 12 gets equal exposure to every learning situtation.

Textbooks used

Phase II training uses five textbooks, including Jacob & Francona’s “Structure & Function in Man”; “Emergency Cardiac Care”; and Miller-Keane’s “Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medical, Nursing and Allied Health.” These are only lent to each student because of the cost (about $75 per set), but about half the group has purchased at least some of the books, especially the lastnamed. Each MED unit gets one set to keep in quarters for reference.

Said Ms. Larsen, “This curriculum is a modification of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s basic course. We put in some things and took out others. We don’t include eight hours on psychology, for instance.

“But there isn’t any one book that says everything I’d like to cover. We may take only a few pages, or a few chapters, from any single text.”

She has just drafted a basic training handbook to fill this need.

“I’m learning all the time how to teach this course better,” she added. “It’s constantly in flux. A lot comes through feedback from the students, and new material comes along from time to time.

“You have to consider the background of the trainees, and the nature of the community being served. For instance, some of our earlier t rainees had a strong background in hyperbaric medicine because of deep tunnel work that was going on at the time. We didn’t include that in the course. But later groups from other communities hadn’t been exposed to it, so we put something in for them.”

Subjects studied

Here is a brief outline of the 13-week 559-hour curriculum:

- Normal anatomy and physiology—functions and components of each of the body’s nine major systems: skeletal, muscular, nervous, digestive, etc. The student should be able to diagram the components of each, with emphasis on the heart and respiration.

- Pathology and therapeutic intervention—head and spinal problems, respiratory system emergencies traumatic and otherwise, cardiovascular emergencies, gastrointestinal problems, OB problems, orthopedics, injuries from cold, heat, poison, etc., pediatrics.

- The EMS system—handling the pulseless, nonbreathing (PNBP) patient, cardiac arrest, IVs, applicable laws and liabilities.

- Manipulative skills—how to obtain patient histories, making physical exams, monitoring patients, use of the bag mask, airways and intubation, using the shock trousers, communications.

Because they are so often encountered, cardiac/respiratory problems take up about 40 percent of the course time.

Quizzes and exams

Weekly quizzes show how well the material is getting across, and identify students needing help. Twice during the 13 weeks, there’s a major written exam. A grade of 75 percent or better is needed for continuance in the course.

Instructors make themselves available to the students 24 hours a day.

“We get lots of evening calls,” Ms. Larsen explained, “especially right before a test.”

Of Ms. Larsen’s staff of four instructors, three are state-licensed physician assistants with at least two years of college plus an extensive medical training program of their own.

At the end of Phase II, the medical director gives an oral exam to satisfy himself the trainees are ready to go on to the next phase of training.

“At this point,” says Ms. Larsen, “they’ve had 13 weeks of fragmented medicine. Now they have to get it all together.”

Field experience

Phase III—supervised field experience for nine weeks. Here the trainees go on regular duty, answering normal calls. Living with them constantly at the fire station, responding with them on all runs, is one of the instructors, who perform several functions.

First, they continually evaluate the trainees. Meetings are held every two weeks. Second, they critique runs, avoiding such review in a patient’s presence if at all possible. To check the trainee’s thinking, the instructor will ask, “Why did you do it that way?” or “Did you consider this alternative?”

For a frequently-called city unit, this field training period would probably expose all paramedics to enough different problems to complete their education. In the suburbs, MED-8’s special problem was too little activity (they now average three runs a day). So tradeoff was worked out with established units outside Glendale. On each shift, one trained paramedic traded with Glendale while the MED-8 trainee worked in the other, busier crew. All vehicles in the county-wide system carry the same supplies packed the same way.

Trainees evaluated

At the end of the nine weeks, instructors use a 17-page evaluation form to grade trainee progress. It contains a number of timed tests. For example, the trainee may get three minutes to properly put the anti-shock trousers on a patient. He may have 30 seconds to pick out what he needs, set up, and put down an ET tube, or start an IV. As Ms. Larsen said, “That’s plenty of time if he knows what he’s doing. But if he has to stop and fumble around for things because he doesn’t know, he won’t make it.”

Then comes Phase IV. Once on unsupervised regular duty, each paramedic must, on his off-time (compensated) report each month to a two-hour at the same time, (morbidity and mortality) conference where all units in the system meet find out why he did what he did and can then discuss this with them.”

State license exam

After a period of time in Phase IV, the paramedic is ready for state licensure. The state board exam has three basic parts. First comes a 200-question (multiple choice) written test. Second, a practical demonstration—similar to the field evaluation of Phase III. This can be waived, however, in favor of certification by the medical director on the basis of field experience. Ms. Larsen keeps track (from the run reports) of the number of times each paramedic has performed various procedures, and certification is possible when the total is sufficient.

Last is a two-section oral exam. A different physician (neither of whom can be the program director) administers each part. In the first, the eandiate gets a written slip outlining a practical emergency situation. He must describe to the examiner’s satisfaction what he would do, how and why. The doctor may interrupt with questions, raise alternatives, etc.

In the second part, using an electronic simulator, the examiner displays some abnormality on a cardioscope, and the candidate must describe what treatment, he would order for the condition.

Communications needed

As paramedic systems continue to spring up around the country—about 300 of them by 1978—an obvious question is: What channel of communication is there for continuing education by exchange of useful knowledge among these people?

“There isn’t much,” Ms. Larsen replied. “Aside from Seattle, Miami, and us, there hasn’t been much published. We haven’t seen anything from Los Angeles in a couple of years.”

A magazine, Paramedics International (P.O. Box 8265, La Crescenta, Calif. 91214) has been published several times a year recently to help service this purpose. The pages of Fire Engineering include a growing amount of EMS material. But there is far more potential communication than can be handled that way. At this writing, the second World Conference on Pre-Hospital Care was being planned for September 19-21, 1979 in New Orleans. Several other meetings have taken place.

A problem here is that few paramedics can expect to attend such gatherings. Those allowed by t ight budgets to travel to distant national or international meetings will usually be officers, managers, administrators whose promotions have removed them from paramedic ranks.

Lack of career ladder

Darin had this comment: “We aren’t a big enough operation to offer a career ladder. Some of these men have leader written right across their foreheads, but to get the promotion they deserve will require them to transfer out of the paramedic service and back into fire fighting.”

This is one of the greatest problems in assigning fire service personnel to EMS work. And it cuts both ways.

As one engine company officer in Seattle recently said, “We lose a lot of good officer material in fire fighting because right now transferring out of the paramedics is discouraged. They say the man will lose all that paramedic knowledge if he doesn’t stay with it. But it’s also true that after long service as a paramedic, the man’s fire fighting skills and knowledge get so rusty he is going to have a tough time with a promotional exam.”

That situation was borne out by a Boeing Company study in the 1970s showing that “procedural and control tasks deteriorate unacceptably in one to four months … in order to maintain a fire fighter’s skills at the peak of efficiency, retraining is an established requirement.”

Block to volunteering

On the other hand, if access to the promotional ladder is blocked, the more ambitious people won’t volunteer for paramedic duty in the first place. Thus, both EMS and fire fighting tend to suffer through policies that make advancement possible only in fire fighting units.

Darin said, “I never saw a successful team, especially a medical team, function without a leader.”

Yet line officers—even staff officers—in the paramedic service are virtually unknown in fire departments today.

In Glendale, MED-8 benefits from some compromise. There is a team leader, who draws 5 percent extra pay, for each paramedic shift. And any paramedic is free to take any promotional examination in the fire fighting division. A trained paramedic replacement, however, must be available before a transfer can be made.

Paramedic burnout

Another touchy concern in the minds of those supervising MED-8’s work is professional burnout.

Said Darin, “We don’t have the problem yet. Our people are so dedicated and well-trained, but it can happen. It happens in medicine. You will see skilled surgeons, after some years, just decide they can’t do it any more, and they switch to some other area of practice. This is another reason why I favor paramedics being part of the fire service. They volunteer for paramedic work, and if they ever feel a need to get out of it, t hey should be allowed to volunteer out again.”

Glendale Fire Chief Bernard Goecks explained the concern his department felt about burnout.

“The new union contract,” he said, “provides that upon written request, a paramedic can return to the fire service. That’s why we make sure our people are getting fire fighting training if they didn’t already have it. Everyone got t hree intensive weeks of that, and they are now sitting in on the classes being given to other personnel.”

Periodic evaluation reports and meetings should show if any individual is approaching burnout without realizing it.

“When they start treating patients like just another job to do, rather than as persons,” added Goecks, “it’s a signal that something has to change. Other team members will see it; they’re going to come to supervision and advise what’s happening.”

Reason for praise

An aspect of the doctor-patient relationship that has been strongly criticized in recent surveys is the tendency toward an impersonal uncaring attitude by the doctor. The emphasis away from that in MED-8’s training is one reason for the praise its work has received from the community, including the medical profession, in the first months of operation.

Said one of MED-8’s crew after going on regular duty, “The training at County was super. They give you a lot and you have to memorize. That’s the only way I have to learn all this stuff, because it’s hard.”

In giving credit to Ms. Larsen for leading that training, Darin described her as “superb—a born teacher.”

From programs elsewhere as well as in Glendale, it’s clear that a successful paramedic operation must build on two bases—sometimes provided by the same person: (1) a dedicated physician who can sell the community on the program, get the profession behind it, and take the responsibility for it, plus (2) a dedicated teacher who can make sure the paramedics learn what they need, retain what they’ve learned, use it properly, and develop the team spirit.