By CRAIG PRUSANSKY

Technology has advanced the capabilities in emergency services dispatching. We have come a long way from having the box number being “tapped” out on a piece of ticker tape and a system of alarm bells in the firehouse. However, is there a point when the dispatching technology may be too advanced? When I was growing up, my father, who worked for IBM, told me about an axiom called the “IBM Pollyanna Principle,” which stated, “Machines should work; people should think.”1

Evolution of Dispatching Systems

Before I delve too far into this concept, let us first see where we came from and how we got here. In 1852, the first municipal fire alarm system was installed in Boston, Massachusetts.2

If a fire were to break out in a building, anyone could run to the nearest alarm box and activate it. It would then send a signal to a central fire alarm office, which would retransmit the box number to the fire stations, tapping out the box number on the alarm bells and on a reel of ticker tape. When an alarm sounded, the firefighters would listen to see if the box was in their response area; if it was, they would respond hastily to the box. Unless they could see a smoke plume, they usually had no idea if they were going to a fire, a cat in a tree, or any other type of assistance call.

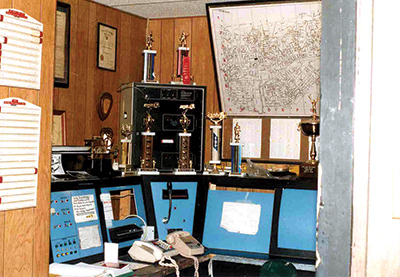

|

| (1) “Plectrons” and voice pagers were the standard for fire dispatching in most of the country in the 1970s through the 1990s. Many places still use this technology. (Photos by author.) |

Then, along came the telephone. In the cities, people could call in their alarms to the alarm office. In the rural areas, there usually was a “party line” set up among the chief’s house, a local store, and the firehouse. When the fire department was called, it rang in all three places. The first one to answer the call went to the firehouse, wrote the address of the call on a blackboard on the front of the firehouse, and activated the siren. The siren could be heard for miles. Everyone then drove to the firehouse to obtain the location of the call.

The 1970s brought about the advent of the radio system and paging. Early paging systems, such as those using the Motorola QuickCall I tones (like they used on the TV show Emergency!), were beginning to be used across the country. Fire stations could be alerted to an incident without everyone having to listen to every alarm. Volunteers could also be notified of the exact location of the call on their pager or “Plectron” and not have to drive to the firehouse first.

Citizens would still have to dial a seven-digit phone number to access emergency services. Between the 1970s and the 1990s, Enhanced 911 (E-911) systems were being installed in dispatch centers across the country so that only one easy-to-remember number could be dialed in an emergency. Today, most dispatch centers in the United States have 911 capabilities.

|

| (2) Some larger cities still use the fire alarm box systems as a backup to their primary means of dispatch. |

The paging systems were also improved for reliability and efficiency. With the exception of “rip-and-run” printers, which printed out the call information for the crews to take with them, computerized station alerting was not yet a reality, except for New York City. The Fire Department of New York (FDNY) had its StarFire system,3 which alerted the stations by computer. It is still in use today. Today, technology is at a point where people are starting to look at ways to improve service delivery, specifically response times.

Time Reduction

Since the newer technology has been available and implemented, I have noticed a trend among more and more fire-rescue communications systems. They seem to be more computerized and less “personal.” The impetus for the computerization has merit. Certain aspects of the time it takes for emergency responses are constants: It takes on average a set amount of time for the dispatcher to obtain the information, for the crews to walk to the truck, and for the truck to get from the station to the scene. Yes, we can “tweak” those actions; but, for the most part, there is a limit on how fast they can be done.

Technology can reduce significantly the times for handling calls-the time it takes a dispatcher to collect the information from the caller, enter it into the computer, and have the computer recommend which units to send to that call-and alerting stations-the time it takes for the dispatcher to alert the emergency crew that there is a call.

In 2006, my department moved from the Motorola Quick-Call II two-tone sequential paging system to Locution, a computer-based solution that alerted the stations by computer voice, which saved from 30 seconds to more than a minute per call. In the case of multiple calls holding, it could have been several minutes. That is a significant decrease in call-handling times; the crews were alerted more quickly and, therefore, arrived at the scene more quickly. The time savings are great, but they can lull an agency into thinking that it could save even more time if everything were automated. Even worse, an agency may assume that computers can replace human dispatchers, which would save money for the department as well.

|

| (3) Mobile data terminals allow responding units to change their statuses and receive updates on the incident without tying up radio time. |

The Personal Touch

Let’s review that IBM axiom again: “Machines should work; people should think.” A machine should make things easier for humans. A machine should never take the place of a human where critical decisions need to be made. In the scope of emergency dispatching, a computer is needed for more than tracking unit status changes. I have seen agencies that have become almost totally computerized and have lost much of the personal aspect of the dispatcher. If you are a dispatcher and are reading this, please do not take this statement the wrong way. I am not saying that the dispatchers have become impersonal (of course, there are some who are, but that is in every agency). What I am saying is that the system has become impersonal. “So what’s the big deal?” you may ask.

When I was a teenager growing up in Dutchess County, New York, I was a fire “buff” (and still am today) way before I was a firefighter. I had a scanner in my bedroom, and I put an antenna on my roof so I could listen to the surrounding departments. FDNY Bronx/Staten Island broadcast its dispatch on 154.190 MHz, and I could hear it crystal clear since the transmitter was on top of the George Washington Bridge and the signal basically shot straight up the Hudson River.

I learned many things listening to FDNY. You could tell by the inflection of the dispatcher’s voice whether the call was “real” or relatively insignificant. I remember reading somewhere that to be an effective dispatcher, you need to have a “calm, monotone voice.” To me, naturally giving your crews a sense of urgency through your voice can mentally prepare them for what they are about to encounter. Even the most complacent crews will spring to life if they hear a dispatcher saying, “Caller reporting heavy fire on the number 2 floor with possible occupants trapped” in a concerned voice on the initial alarm instead of a monotone “residential structure fire.” The dispatcher doesn’t have to get excited; the dispatcher’s natural voice should be enough to convey the tone to the crews.

|

| (4) Newer dispatch centers have become computerized, minimizing radio traffic and increasing the efficiency of the responding units. |

There are some other disadvantages to using solely a computerized system with no or very limited human interaction. The use of mobile data terminals (MDTs) is becoming more prevalent in emergency services. They are great for high-call-volume areas because they reduce the radio traffic significantly by allowing the units to change their own statuses without having to tie up valuable air time. The problem is when they are used on multicompany operations such as fires and vehicle accidents. Other units responding to the scene have no idea of what is going on at the scene. They also have no idea of the action the first unit is taking. Most departments have in their standard operating guidelines rules about verbally transmitting “benchmarks” like arrival reports and changes in conditions so that other units and the incoming chief/commander can know what is happening and how the scene is progressing. That is fine, as long as the agency is willing to put that into its guidelines.

Another disadvantage is related to the station- and unit-alerting process. Many departments are switching to a computerized station-alerting system in which the units are notified by a computerized voice, a visual indicator, or both, inside of the firehouse. The alert is sent by computer line instead of over the radio, so it cannot be heard outside of the firehouse. The units being dispatched to the incident also get the call on their MDT if they are out of the firehouse. Unless there is a means of announcing the calls, an emergency vehicle might be right in front of a call and not even know it if it is not the one recommended by the dispatch system. Some departments have a dedicated “announcement” channel that announces the calls, but it is independent of the station-alerting system so that “stacked” calls on the “announcement” channel do not delay the calls being sent to the stations. Other departments “voice announce” the call over the operating channel after the station has been alerted.

The final disadvantage I will discuss has to do with the ability for a human to “think” if the computer makes a wrong decision. Many departments have a “main” dispatcher (in my department, the position is called “Fire Main”; in FDNY, it is called the “Decision Dispatcher” (3); and in other places, it is called the “Gatekeeper”) who verifies the recommended response and can change it if it is not correct. There have been times when the computer in our Communications Center made a wrong recommendation. It takes a competent human dispatcher to recognize this and make the appropriate changes.

Some departments use the computer to assist them with moving units around to provide coverage. Although this reduces response times by ensuring that the correct types of units are dynamically allocated in the most efficient manner, there are times when a human dispatcher needs to make sure that what the computer recommends is in fact the most efficient. Sometimes, what the computer thinks is logical is in reality not feasible because the computer did not take into account a variable that was not able to be entered into the algorithm to calculate how the vehicles should be distributed. I have seen how an incorrect recommendation by a computer could have disastrous results in response times when the error is not caught by a human dispatcher or, as in this case, when a dispatcher is not allowed to override the computer’s recommendation.

As much as I am a pro-technology person, I also think that no matter what, we will always need the human factor in our dispatching. Computers are only as accurate as the humans who program them, and there should always be a checks-and-balances system involving a human dispatcher when life and property are involved. This is especially true for those calls when everything is “going south” and you need that competent voice on the other side to pull everything back together.

Endnotes

1. Marvin, Steven. Dictionary of Scientific Principles. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011.

2. Sweeney, Emily. “No Cause for Alarm,” Boston Globe., Jan. 27, 2008.

3. The New York City Department of Investigation. “DOI Investigation into Delay of Ambulance Dispatch to Queens Fatal Fire in April 2014 Reveals Significant Ongoing Flaws in Overall System.” Press release, Oct. 21, 2014.

CRAIG PRUSANSKY, EMT-P, is a district captain and a 24-year veteran of Palm Beach County (FL) Fire-Rescue. He served as the department’s systems analyst from 1998 to 2001. He is the EMS quality improvement coordinator for the department as well as the project manager for its ePCR system implementation. He was a police and an EMS dispatcher prior to being a firefighter.

Related Links

Handling the Mayday: The Fire Dispatcher’s Crucial Role

Dispatcher’s Guide for WMD Incidents

Getting Critical Dispatch Information

To request information go to fireeng.hotims.com

Fire Engineering Archives