By Joe Pulvermacher

Engine 183, Med 183, Battalion 18: Respond to 7912 S. Howell Avenue for the report of a fight in the parking lot. All units stage until police have made contact.

Dispatch from Battalion 18: Be advised we are en route. We will be approaching from Rawson. All units will stage on Howell …. Dispatch, did you copy? …. Dispatch? …

All Fire Department Units from Dispatch: Be advised … shots fired! … unable to contact officer on scene … unknown number of shooters ….

On a beautiful Sunday morning, without warning, a gunman paced the grounds of the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin and started shooting those in his path. Everything about our active shooter response was about to be challenged: Was the shooter still shooting? Were there more shooters? How many people were injured? Was it possible to get to the injured officer?

For the past 10 years, the Oak Creek (WI) Police Department (OCPD) and Oak Creek (WI) Fire Department (OCFD) had practiced for an active shooter incident, primarily with special weapons and tactics (SWAT) and tactical emergency medical services (TEMS). But, when analyzing response times and the need for immediate medical care, we knew that a SWAT/TEMS response was not going to be fast enough. This observation necessitated a closer look. We needed to establish a policy and procedure to address the active shooter incident with personnel and equipment available on the initial response. As with many fire service initiatives, our timeline was expedited by actual events. Unfortunately, our response had not been practiced prior to the Sikh Temple Active Shooter.

On August 5, 2012, the OCFD daily staffing was 13 firefighters (minimum staffing) assigned to three fire stations. Not all stations were notified on the initial dispatch because of the preliminary information received. As a result, the emergency medical equipment immediately available was limited to two paramedic ambulances, a two-person engine crew, and a battalion chief. As calls continued to flood dispatch, the report of injuries continued to grow. At one point, it was reported that up to 35 people were injured and unable to get out of the temple. All available OCFD personnel and equipment were dispatched to the scene, and additional mutual-aid ambulances were called to assist with the mass-casualty potential.

After all rooms were cleared and the scene was determined to be controlled, we determined that four people were injured (including an OCPD officer) and seven people were dead (including the shooter). Treatment and transport were conducted with minimal coordination, and questions loomed about safety and response (which resulted from limited preparation and practice). Information covered during our after-action critique demanded an improved response. So, police and fire representatives worked on the implementation of a rescue procedure for incidents that involved a less-than-safe environment.

To address the best practices associated with tactical medicine, we engaged in applied research, which addressed the continuum of care, response effectiveness, difficulties encountered, communication/command, and response acceptance. Research procedures accounted for involvement at the community (bystander) level, local emergency responder level (OCFD and OCPD), and regional level (mutual aid). The results provided insight into the OCFD’s systematic approach to the implementation of the Hartford Consensus and the U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) Active Shooter Guidelines.

Continuum of Care

Response to an active shooter incident involves much more than the availability of police officers and firefighters. It may be several minutes before emergency responders will be able to enter the building and access patients. Even if entry is made immediately following the arrival of the police and fire departments, not all of the injured will receive immediate care. Oak Creek initiated a First Care Initiative, developed collaboratively by the OCPD, the OCFD, and the Oak Creek Franklin Joint School District (OCFJSD). It empowered bystanders to slow down bleeding and protect the airway of wounded victims. By the end of the first quarter of the 2013-2014 school year, approximately 95 percent of the school district’s administration, faculty, and staff received active shooter training.

Prior to implementing collaborative care in August 2013, the active shooter policy in the school district was limited to locking down the classroom and sheltering in place. The revised policy provided a more realistic expectation. Faculty and staff were given more information about preventing active shooter incidents through the OCPD’s “Hear Something, Say Something” program. Further, school district employees were given more options when responding and reacting to an active shooter; lockdown was no longer the only option. Faculty and staff were taught the principles of Homeland Security’s “Run, Hide, Fight” and Texas State Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training’s (ALERRT’s) “Avoid, Deny, Defend.” If it is realistic to leave the building, the OCPD cited better outcomes when potential victims got farther away from the area of conflict. Educators were also given information about protecting themselves and their students. They were instructed in methods used to defeat the shooter, especially when the shooter gains entry to a room that has been locked down.

The primary focus of the information the OCFD presented to school district employees in the First Care Initiative training was on hemorrhage control. Tourniquets, emergency bandages, and hemostatic agents were introduced at the bystander level. The intent was to use faculty and staff as a force multiplier (the use of existing on-site personnel and equipment to enhance the typical emergency response). One teacher observed: “[During an active shooter situation in the schools, teachers] are the real first responders if you really think about it.” The OCFD also introduced tactical emergency casualty care (TECC) supplies and procedures into the school district’s educational environment.

By the end of the 2013-2014 school year, funds had been raised to cover the cost of 150 trauma kits for schools, including the city’s private/parochial schools. At the time this article was written, almost one-third of the kits were assembled and installed in Oak Creek schools. Private corporations/organizations and parent/teacher organizations continue to raise funds to purchase kits for all OCFJSD classrooms. Community-based TECC is also expanding to Oak Creek’s civic buildings. Oak Creek City Hall has trauma bags in the building’s shelter-in-place areas. Some employees who conduct business at City Hall have been trained in hemorrhage control and airway management.

Police

The Hartford Consensus guidelines stipulate that law enforcement must actively train in hemorrhage control. Since 2011, the OCPD has equipped its squad cars with tourniquets and emergency bandages. Through instruction and training evolutions, the OCPD has instituted TECC training for all officers, and OCFD TEMS operators have functioned as TECC trainers. Since 2012, 100 percent of all OCPD officers have been trained in TECC, and all have been equipped with a tourniquet. Within the past year, all OCPD squad cars have chest seals and hemostatic agents.

|

| (1) The front of a ballistic ensemble with IFAK. (Photos courtesy of author.) |

Should there be an active shooter situation, police officers will grab a “go bag,” which contains additional ammunition, disposable handcuffs, a drag strap, and TECC supplies. Kits are equipped to provide first aid for self-care/buddy care/casualty care. However, officers will not stop to render care unless the shooter (threat) has been stopped.

Firefighters

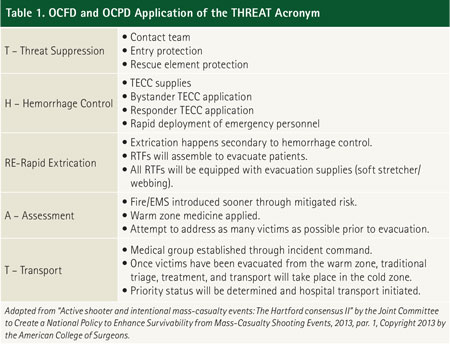

This research also resulted in a more aggressive approach from firefighters. OCFD firefighters were instructed in scene dynamics and advised of the updated response plan for active shooter incidents. All sworn-in OCFD members were introduced to the TECC application, terminology, and rescue task force (RTF) concepts. The firefighters were told that it was not realistic to wait until the scene was determined to be safe before administering patient care. During an active shooter incident, the OCFD will provide patient care in areas of mitigated risk. Joint police and fire active shooter training was instituted by early 2014, and all of our police officers and firefighters received introductory training. RTF positions and movements were reinforced through repetitive training. Further, OCFD and OCPD policies, procedures, and directives were classified according to the THREAT acronym established by the Hartford Consensus and reinforced through the USFA’s Active Shooter Guideline (Table 1).

|

| (2) The back of a ballistic ensemble. |

Mutual Aid

Understanding the importance of a regional response, we evaluated procedures for mutual-aid compatibility. A police and fire ad hoc committee was established to address response uniformity. The purpose of this research was not to evaluate the response of mutual-aid departments during an active shooter event. However, the OCFD’s ability to move forward with an active shooter response was contingent on the direction of the Milwaukee County Fire Chiefs Association (MCFCA). Since a suburban response is likely to involve participation from mutual-aid agencies, this step ensured that when other fire and police departments develop response guidelines, response procedures would be similar. A guidance document was written and presented to Milwaukee County area police and fire chiefs at the end of May 2014. The police and fire chiefs approved the information as presented; a police and fire train-the-trainer program was developed to improve the chances that procedures would be uniform for all departments.

|

| (3) A drop bag. |

Response Effectiveness

The effectiveness of response was evaluated on the levels of bystander response and fire/EMS response, which were evaluated separately. At the end of May 2014, a feedback instrument was distributed to all school district employees through the superintendent’s office. The instrument contained the same questions used in a 2012 feedback instrument that evaluated a K-12 response to tactical mass-casualty incidents. School district employees could comment anonymously through this medium. Of the more than 800 school district employees, 170 responded. A report of the responses was produced so that 2012 and 2014 data could be compared. The following responses assisted in determining the effectiveness of bystander-applied TECC.

OCFJSD

- Active shooter response awareness. In 2012, 63 percent of all school district respondents indicated that they were aware of the OCFJSD’s response procedures to active shooter incidents. In 2014, 95 percent indicated that they were aware of the district’s response procedures. The increase in procedural awareness reinforces that active shooter education positively impacted readiness.

- Individual responsibility awareness. In 2012, 68 percent of all school district respondents indicated that they were aware of their individual responsibilities during an active shooter incident. In 2014, 98 percent indicated that they were aware of their individual role during active shooter incidents. Once again, improvements were noted after active shooter training.

- Response proficiency. In 2012, 55 percent of all school district respondents indicated that they were proficient or knowledgeable in the application of an active shooter response. In 2014, 88 percent of all respondents indicated that they were knowledgeable or proficient. Similarly, in 2012, 18 percent felt that they were not prepared for an active shooter incident. In 2014, less that one percent felt unprepared.

|

| (4) A drop bag deployed. |

Fire/EMS

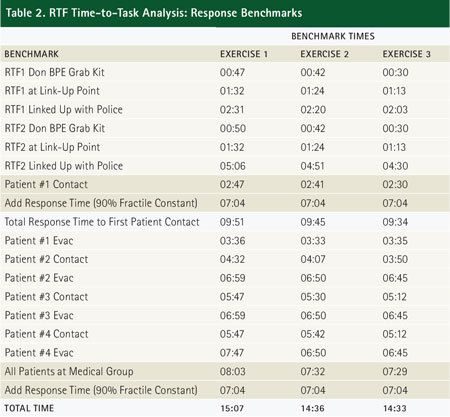

We conducted a time-to-task analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of the fire/EMS response. Times collected provided information about RTF assembly, patient contact/treatment, and patient evacuation. Response times (dispatch to arrival) were simulated using the OCFD’s 2013 response data. In 2013, the OCFD’s 90 percent fractile response time was 7:04 minutes (OCFD, 2014). Adding the simulated response time to the times collected during the OCFD’s active shooter exercise provides a projection for RTF effectiveness. The OCPD and the OCFD have established a 10-minute benchmark to make initial patient contact with the RTF and a 60-minute benchmark to have all patients evacuated. In this time-to-task analysis, the entry benchmark and the total victim treatment benchmark were prioritized. All rotations were timed, and collected times were used to ensure that benchmarks were being achieved.

|

| (5) An IFAK open/deployed. |

Three exercises were recorded (Table 2). In all instances, response benchmarks were achieved. Patient contact was made within 10 minutes (longest = 09:51), and all patients were extricated within 60 minutes (longest = 15:07). Simulated deceased victim assessment times were not recorded. Responders spent very little time with deceased victims; nonbreathing patients and those with injuries incompatible with life were bypassed.

During OCFD’s real-life active shooter experience, initial patient contact was accomplished early in the incident. However, police protection was not made available (or at least communicated) to the emergency medical responders. This research reinforced the need for mitigated risk and the effectiveness of policy and procedure in a less-than-safe environment.

Difficulties Encountered

Community-based continuum of care (TECC) resulted from the need for hemorrhage control immediately following a traumatic event. Active shooter incidents can happen at any time and often surprise those in the immediate area of the event. Hopefully, those who witness an active shooter event will provide assistance quickly and become involved in patient care. With that, it is important to train as many people as possible in the life-saving practices of TECC. Unfortunately, some school district staff members did not receive the active shooter training. We concluded that front office and custodial staff will participate in reoccurring training.

Initially the OCFD’s active shooter response provided care and extricated patients as casualties presented. Mirroring Israeli mass-casualty care, an “Assess, treat life threats, grab, and go” approach was considered. Initially, a “grab and go” approach seemed appropriate, especially when victims did not outnumber responders. However, when the number of victims is greater than the number of responders, treatment must be prioritized.

Difficulties were encountered in providing quick hemorrhage control during mass-casualty incidents; priority patients were being missed while patients with less significant injuries were being evacuated. The longer a patient was left to bleed, the greater the possibility of irreversible blood loss. The OCFD’s policy was updated so that responders could provide hemorrhage control to as many people as possible.

The OCFD worked with various TECC kit configurations. Large kits provided more equipment, but they hampered movement. If a kit was too small, supplies were limited. The kit needed to be small enough to be carried on the person, large enough to carry multiple supplies, functional enough to work out of when fine motor skills are compromised, and affordable enough so that all medical responders could have one attached to their personal protective equipment. The OCFD found a kit that could open completely, had enough room to carry multiple supplies, and was able to attach to the responder. Working in pairs, fire/EMS providers have enough supplies to treat multiple injuries/injured. However, during a mass-casualty situation, when supplies are used in larger quantity, RTFs will also have the option of carrying a drop bag (resupply bag). Drop bags can be carried into the warm zone and be dropped in the casualty collection point or be used at the point of wounding.

We also considered evacuation equipment. Initially, evacuation supplies (soft stretcher webbing) were carried as needed and by assignment. Training evolutions reinforced that all RTFs need to carry evacuation supplies regardless of primary function (treatment or evacuation). Two examples provide background for this decision. Unlike schools, large manufacturing buildings, warehouse complexes, and cubicle-partitioned office spaces may not have easily communicated landmarks (such as room numbers). Victims may have to be moved to expedite evacuation, especially when the location of the victim is hard to identify and landmarks are difficult to communicate over the radio. Additionally, when patient care has been completed, it is important to optimally use personnel and equipment. When RTFs have the ability to treat and evacuate, they can adapt to the needs of the situation and make decisions based on the variables of the incident.

Ballistic protection is necessary in the active shooter environment. Even though the risk in a warm zone environment is mitigated, active shooter incidents are not without risk. Emergency responders must continually evaluate their work environment. If law enforcement is entering the scene with ballistic protection, emergency medical providers need to consider similar ensembles (vest and helmet). Until recently, the fire service has not typically been involved in active, tactical incidents. As a result, ballistic protection has not typically been funded through the local budget, state funding, or federal funding. Furthermore, it is difficult to find grants that allow ballistic protection for firefighters. The OCFD has a few sets of ballistic protective equipment; however, more ensembles are needed to equip all first-line fire and EMS personnel. The specifications for the OCFD’s ballistic ensemble will minimally include the following:

- Ballistic plates/plate carrier (level III+, steel).

- Ballistic helmet (level III with ratchet suspension and adjustable chin strap).

- Individual first aid kit (IFAK) with TECC supplies.

- Egress soft stretcher.

- Optional drop bag (with additional TECC supplies) (photo 1).

Difficulties were observed in the implementation of local policy. As the OCFD’s active shooter response procedures were being instituted, a neighboring major metropolitan fire department was establishing its own response. Other neighboring fire chiefs expressed concern about mutual-aid support and the standardization of an active shooter response. As with many emergency operations, variables exist at the local level. The OCFD’s active shooter response procedures closely resembled the active shooter response of the OCPD. Implementing another fire department’s policy would not resemble the collaborative effort that took place between the OCFD and the OCPD. At the conclusion of this debate, it was unlikely that one uniform policy would exist. However, through the fire and police ad hoc committee, a guidance document was developed so that terminology and methods would be similar.

Communication and Command

When the OCFD’s operations battalion chief arrives on the scene of an active shooter incident, the incident commander (IC) (police) requests vital information. Experience gained from the Sikh Temple incident revealed that communicating with command through dispatch will be difficult. Dispatch will be overwhelmed by police activity and other telephone calls. The OCFD’s active shooter procedure enables the battalion chief to communicate with the IC over the police frequency. Training identified difficulties when using multiple radio channels. The OCFD’s battalion chief (Fire Operations) is responsible for monitoring the OCFD’s primary dispatch, the interagency fire emergency radio network (IFERN mutual-aid channel), MABAS Red (tactical channel), and the OCPD’s primary dispatch channel. During training, while the RTF was operating inside the warm zone, the OCFD’s battalion chief was monitoring transmissions on the police and fire frequencies. When police officers and firefighters transmitted similar information at the same time, radio transmissions were confusing. To address this concern, once the RTF is formed and firefighters are linked up with police officers, the battalion chief can discontinue monitoring the police frequency. The RTF will provide a natural communication bridge, as firefighters will remain on the assigned tactical channel and police officers on their primary frequency.

Considerable discussion took place about incident command and unified command. Some fire departments have indicated that they will not initiate an RTF response without unified command. Although the OCFD appreciates the value of unified command and a coordinated command structure, experience has shown that Oak Creek’s unified command structure will not be instituted immediately. In the suburbs, during an active shooter incident, front-line police supervisors will likely be involved in operational elements of the incident. Unified command may not happen until off-duty command staff personnel have been called to the scene. Waiting for a formal unified command structure to form will likely stifle the rescue effort. Time waiting is equivalent to time bleeding. The OCFD has prioritized RTF functions over unified command with the understanding that command staff functions are important and unified command positions must be filled quickly

Response Acceptance

In the response continuum, school district employees and firefighters experienced the most significant cultural change. Acceptance drives emotion, and emotion impacts initiative and procedural application. The results of this research evaluated the acceptance of the bystander’s role during an active shooter incident and the firefighters’ pre- and post-training impressions.

- Perception about active shooter incident potential. In 2012, 11 percent of school district respondents indicated that it was probable/likely that an active shooter incident would happen in the school district. In 2014, 25 percent of respondents indicated that an active shooter incident was probable/likely. The OCFD/OCPD stressed readiness and predictability of response. Readiness is often accomplished through visualization and incident anticipation. Those who feel that an active shooter incident is not likely to develop will be the most surprised and least prepared when an active shooter situation occurs. The OCPD and OCFD emphasize that training should be conducted with the expectation that skills learned could be used at any time. In 2014, more school district employees indicated that an active shooter incident is probable.

- Initial medical treatment during active shooter incidents. In 2012, 63 percent of school district respondents indicated that teachers and school staff would be performing initial medical treatment. In 2014, 91 percent of all respondents indicated that teachers and staff would most likely perform medical treatment. Faculty and staff were asked, “Who is most likely to perform initial medical treatment?” Comparative data from 2012 and 2014 indicate that more faculty and staff accept the fact that the emergency response will begin with them. The results of this inquiry reinforce the need for community TECC training and bystander awareness.

- Expectations of professional emergency medical response. In 2012, 77 percent of all school district respondents indicated that a professional EMS response would happen within the first 10 minutes of the incident. In 2014, the expectation shifted to longer response times. In 2012, the need for bystander first aid/trauma care was not prioritized. The expectation and perception of an emergency medical response suggested that firefighters/EMTs would arrive quickly and take care of the injured. The OCFD and OCPD active shooter program provided insight into an actual active shooter response. Although firefighters have made significant progress in the delivery of emergency medical treatment in a tactical environment, realistic expectations have been shared about the response timeline. The 2014 data reflect a shift in response time: More school district personnel indicated that it will take time for a professional EMS response. Longer response times strengthen the acceptance of community/bystander TECC.

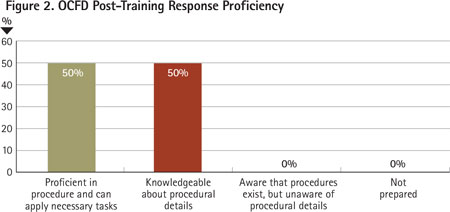

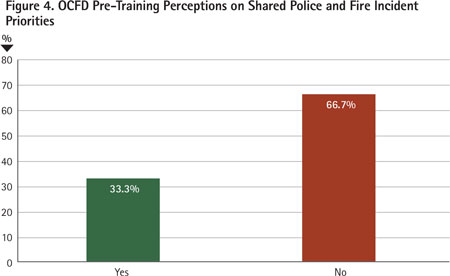

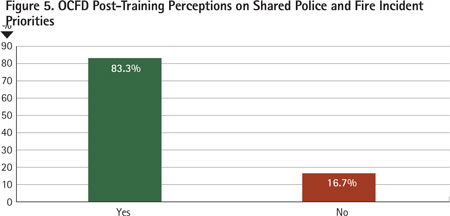

Firefighters were also given the opportunity to comment on the OCFD’s active shooter response. Results provide insight into acceptance and readiness. Pre- and post-training feedback instruments were circulated and data were recorded.

Figures 1 and 2 depict the OCFD’s response proficiency pre- and post-training, respectively. Improvements were noted in response proficiency. Respondents expressed a better appreciation of active shooter initiatives after participating in joint police/fire training. For firefighters to accept an active shooter response, they have to understand their role in the continuum of care and convey knowledge in policy and procedures. Prior to training, firefighters were asked if they had any concerns about an active shooter response. Respondents wanted to ensure that scene safety was considered and that protection was provided to emergency medical providers. In the post-training feedback instrument, with the exception of one firefighter, those who attended indicated that the training addressed their concern (Figure 3). The firefighter who continued to express concern stated that the training “somewhat” addressed response concerns. In the narrative provided, the firefighter still questioned the effectiveness of communication.

- The perception of a shared response. Respondents were asked if the OCPD and OCFD had shared priorities. Prior to training, most firefighters indicated that police and fire priorities were not shared (Figure 4). Following joint police and fire active shooter training, with the exception of one firefighter, all feedback respondents indicated that police and fire incident priorities are shared in an active shooter incident (Figure 5). The firefighter who had concerns about the active shooter response expressed concern about firefighter and police officer roles. Mutual-aid compatibility was also questioned.

Results for this research confirm that progress has been made in the OCFD’s implementation of an active shooter response. Research supports the OCFD’s bystander and emergency responder initiative. Feedback received and data collected confirm that the OCFD’s active shooter continuum of care is effective and accepted. Further, difficulties encountered are being addressed and improvements to response are continually being made.

Those looking to institute an active shooter response should evaluate all levels of the care continuum-bystander/community TECC, law enforcement self-care/buddy care, fire/EMS RTF operations, and mutual-aid support impact patient survivability at different levels of the response. No policy or procedure is “the” policy or procedure. Instituting this initiative is a collaborative process among various agencies. Involve the school district in community TECC, the police department in the local RTF response, and neighboring municipal departments in mutual-aid support. Work toward uniformity and standardization, but realize that variables exist in every agency; response procedures will need to be written to address the initial local response.

RTF and active shooter procedures are relatively new to the fire service. Anticipate difficulties, and carefully consider adjustments. While implementing, make sure the message is well-defined. Set some clear expectations about RTF techniques and active shooter response. Decisions may be influenced through logic, but motivation is inspired by emotion.1 Get assistance from those within the organization who are passionate about the project. Training will be continual; the department is going to want to establish some in-house experts. It will be equally important to institute an external network so that lessons can be learned through others’ experiences.

Through applied research, the OCFD was able to implement its active shooter/tactical mass-casualty response procedures. Moving forward, the OCFD must consider how to best use mutual-aid companies responding into Oak Creek and determine how it will support active shooter incidents when responding to neighboring communities. Joint training among police, fire, and mutual-aid departments will help establish incident predictability through repetition. Training will make this response more effective, and repetition will ensure that the response initiatives are accepted. New police officers never question the role of the patrol officer during active shooter incidents. Fifteen years ago, that wasn’t the case; law enforcement was going through its own paradigm shift. Given time, the fire service may look back at this transitional period and wonder why the response was ever questioned.

Note: Information for this article was adapted from the Results and Recommendation sections of the author’s National Fire Academy EFO Applied Research Project pertaining to the Implementation of an Active Shooter Response (Executive Leadership): http://www.usfa.fema.gov/pdf/efop/efo48752.pdf

Endnote

1. Hiatt, JM. (2006). ADKAR: Awareness, desire, knowledge, ability, reinforcement: A model for change in business, government and our community. Prosci Learning Center, Loveland, Colo.

JOE PULVERMACHER was recently appointed chief of the Fitchburg (WI) Fire Department. He previously served as the battalion chief of training for the Oak Creek (WI) Fire Department. He has a bachelor’s degree in fire service management and is certified as a Wisconsin level II fire officer and level II fire instructor. He is an Executive Fire Officer through the National Fire Academy and a charter member of the Oak Creek Tactical Emergency Medical Support Unit.

Joe Pulvermacher will present “Active Shooter Response: Oak Creek (WI) Fire Department’s Approach to Rescue in the Warm Zone” on Wednesday, April 20, 3:30 p.m.-5:15 p.m., at FDIC International 2016 in Indianapolis.

Engine Company EMS: Active Shooter /Mass Casualty Response

Two New Training Programs on Active Shooter Response

Lone Wolf/Active Shooter : Attack on Texas Public Safety Building

Fire Engineering Archives