BY MICHAEL L. KUK

In the 1940s, several hotel fires occurred that caught the respective fire departments off guard in the suppression and rescue phases. Firefighters in large and small cities had to face challenges that tested the ranks of their bravest, with no room for error.

Along the Mississippi River in Dubuque, Iowa, a rapid hotel fire in the summer of 1946 would take 19 lives, severely injure more than 30, and leave mental scars on the guests and local firefighters for the rest of their lives.

The Hotel Canfield first opened as the Hotel Paris in 1891 at the corner of West Fourth Avenue and Central Avenue, overlooking the Mississippi River. It would become infamous years later because of a small trash receptacle fire that moved rapidly throughout the structure, enveloping guests and employees in a whirlwind of fast-moving smoke and a hungry fire that devoured every piece of combustible material in its path.

A wood-based product impregnated with flammable glue fueled the rapid fire spread, the fire department wasn’t notified for at least 15 minutes, and a haphazard series of missteps by guests and hotel staff after the fire’s discovery left precious little time for escape. One significant forgotten fact about this incident was that responders using a single life net saved 27 lives, the highest number ever for the device.

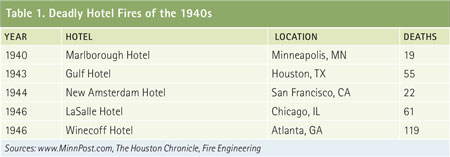

Deadly Hotel Fires

With the end of World War II, millions of people started traveling again throughout America in 1946, enjoying the comfort and the convenience of the finest hotels. Many had no idea that fire could cause such a high loss of lives in some of these “fire-resistive” hotels.

In the preceding decade, hotel fires plagued American cities, especially since the skyscraper style of construction pushed buildings ever taller. Several hotel fires occurred and took numerous lives (Table 1).

But when it comes to fire safety, it seems the public and fire officials have to learn the lesson repeatedly before they take action. Looking back, I wonder why hotel managers and owners, fire department inspectors, and city officials did not anticipate the potential deadliness of fires in older hotels. After all, many of these hotels were built years before, near the turn of the 20th century, and were deficient in nearly every aspect of fire-safe construction.

Fire protection and safety were traded for heating and air conditioning, comfort, convenience, and space. It was easier and cheaper to allow these buildings to continue to operate and function until something serious happened. No one wished to consider the consequences of a fire in these structures.

|

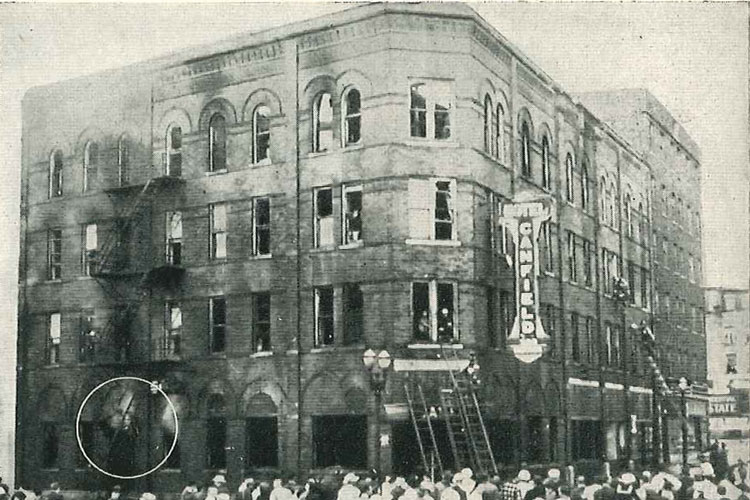

| (1) Operations at the 1946 Hotel Canfield fire involved the original four-story 1891 Paris Hotel section. The circle shows where flames prevented the use of the fire escape. The taller 1925 addition is to the far right. (Photos 1, 5, and 6 courtesy of Fire Engineering.) |

The Fire

On the evening of June 9, 1946, just three days after the tragic fire at the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago, Illinois, the Hotel Canfield would become part of the tragic American hotel fire history.

The Canfield consisted of two parts. The fire occurred in the original four-story 1891 structure, The Paris Hotel. In 1925, the Canfield family acquired the hotel and renamed it the Hotel Canfield. A modern six-story, fire-resistive annex was added that year. This section did not burn in the 1946 fire but suffered heavy smoke and considerable water damage. The newer construction featured fire doors that protected the floors of the new section where its corridors joined those of the 1891 structure.

An extensive investigation found that the probable cause of the fire was improperly discarded smoking material. After the hotel’s Red Lounge closed for the night, it was a long-standing practice to empty all ashtrays into a cardboard waste container in a closet near the bar. A newly hired cocktail waitress told fire investigators that she was instructed to do so and thought it nothing unusual or that a fire would ever result from these actions.

Shortly after midnight, fire broke out in the closet. When it was discovered, several employees and patrons tried to extinguish the flames with small containers of water but with no success. Although a nearby soda-acid extinguisher was used, its narrow stream did nothing to contain the increasing fire. Witnesses reported that probably 15 minutes were wasted during these attempts before anyone thought of calling the fire department.

|

| (2) The Hotel Canfield today. The 1891 section was attached to the left side of the building (Photos 2-4 by author.) |

The drop-down ceiling and many interior walls were paneled with a wooden fiberboard, a popular finishing material at the time. This fiberboard included a flammable glue base for its main adhesive with an alcohol activator to promote a rapid cure during installation.

Once the fire grew beyond its incipient stage in the closet, it roared to life. Witnesses stated that fire attacked the fiberboard as if it had been soaked in gasoline. Patrons told investigators that the flames spread quickly across the ceiling, much like someone knocking over a pail of water on a floor.

The hotel manager, William Canfield Jr., was near the lounge at the initial outbreak of the fire. He suffered serious burns trying to extinguish the growing fire with a soda-acid extinguisher. After the fire, he remained in a hospital burn ward for several weeks.

Unfortunately, both of his parents perished in the fire. His father, an invalid, died in his room. Canfield’s mother died en route to the hospital after she was rescued in the heavy smoke. William Canfield Jr. was unable to attend their funerals because of his own severe burn injuries.

Finally, at 12:39 a.m., someone pulled a street corner fire alarm and, at the same time, an unknown caller, possibly the hotel night clerk, phoned the fire department. The caller was quite upset about what she was witnessing and reporting, saying, “Send the works.” The fire alarm operator quickly told the fire crews at the Dubuque Fire Department’s (DFD’s) central station on West Ninth Street, a short distance from the Canfield, that something very serious was underway at the hotel.

Initial Response

Two engine companies, a hose wagon, and one 85-foot aerial responded to the burning Canfield. In the nighttime darkness, responding firefighters could see a plume of orange-tinged smoke several blocks away. The smell and concentration of smoke stung firefighters’ eyes and nostrils when they were about two blocks away. Senior Captain Harold Cosgrove, acting assistant chief, knew that it was a serious fire.

Cosgrove was on the lead engine and on arrival had a roaring first-floor “blowtorch” that had enveloped the only outside fire escape in the old section. He was also faced with flames issuing forth from the third and fourth floors. People were screaming from the upper stories and shouting for the firefighters to rescue them! He knew that fire suppression would be his second priority and that rescue was paramount.

|

| (3) The different colored brickwork extending to the fourth floor indicates where the original 1891 Paris Hotel was connected to the six-floor 1925 addition. Fire doors prevented fire extension into the newer section. After the fire, the older portion was torn down. |

A general alarm was sent back to headquarters for the rest of the city’s apparatus and all off-duty firefighters to respond. This brought four additional engine companies and two city service ladder trucks to the scene. A total of 57 firefighters, including the chief, eventually responded to the burning hotel. Within 25 minutes of the recall, all of the DFD’s firefighters were on scene and working feverishly.

“Strip the truck” and “raise the big stick” were the first commands that Cosgrove shouted to his truck members. The engine and hose company firefighters quickly started throwing the aerial’s ground ladders to upper-story windows where any guests were visible.

The first-due complement of 17 firefighters arrived from the central station. The outlying stations responded to the general alarm with an additional 10 personnel. These firefighters were sorely needed during this critical phase.

Get the Net!

Faced with too many people needing rescue and knowing that ladder work was slow and laborious, Cosgrove told an engine company officer to “get the net” and go for the smoky side of the structure. Four firefighters brought the heavy life net to the front of the hotel.

When they got the net in place, the smoke became extremely thick and hugged the ground. The thick smoke seemed to paste itself on the building’s exterior walls, totally blocking anyone’s view of the upper portions of the hotel. Upward visibility was severely limited. Terrified shouts from above guided the life net personnel in adjusting their position.

Cosgrove called on several nearby civilian men to come and help hold up the life net. The 10-foot-diameter net required between 12 abd 15 personnel to deploy it correctly. These initial 10 citizen-rescuers were a key element for the net to succeed in capturing jumpers.

Just as the net was being readied, a female jumped and missed the net entirely; she died immediately on hitting the pavement. Another woman also quickly followed, but her head hit the edge railing of the life net, making a large bow in the iron frame. She later died from her head trauma. This terrific impact almost knocked over one of the firefighters, but luck prevailed so that no rescuer got killed from the heavy impact of a jumper.

The toughest net catches were of guests jumping from the highest floors. The impact was severe when they did not land near the center of the net (marked with a red circle), where the force of their fall could be distributed equally. In those cases, the net holder nearest to where the jumper landed received the overall force of the impact at the edge of the net.

In the weeks that followed, all of the personnel who worked the net sought medical treatment to relieve their back, neck, and other injuries. Some never recovered and lived with various degrees of back and neck distress for the rest of their lives.

In the chaos and confusion, some of the jumpers tossed their luggage onto the net before they jumped. Some of these bags ricocheted against the net holders, injuring them. One civilian rescuer’s face was severely lacerated by a jumper’s foot as that person bounced on the surface of the net after landing on his luggage.

The life net crew quickly removed victims off the net, but they barely had time to prepare before the next body struck the canvas. Sometimes they had to shift their overall position as much as five feet since the bodies were coming down at irregular intervals of time, space, and location.

|

| (4) A fire department ladder and the life net used to save 27 lives at the fire, the only time it was used. |

Jumpers from the fourth, fifth, and sixth floors perceived the red circle in the center of the net as the size of a silver dollar and found the “sudden stop” they experienced landing in the net very harrowing.

The persistent smoke conditions plagued the jumpers in visualizing how and where to jump into the safety of the net. It hampered almost everyone’s view of the street and the location of the net prior to their jumping. The life net crew was similarly afflicted in positioning the net.

Overall, the net rescues took about 10 minutes, according to Cosgrove’s testimony during the investigation. He stated that 27 jumpers were successfully caught in the life net. He further testified at the inquiry that the trapped hotel patrons were coming down almost nonstop. There was no delay in removing the latest jumper from the net before another was on the way down.

Firefighters used ground ladders and the aerial to rescue 35 permanent and overnight guests; this encompassed 40 minutes of fireground activity. Anyone who was not rescued from the older section of the Hotel Canfield within the first 15 minutes probably died in the flames and smoke, since the roof collapsed at that time. Portions of it were starting to fail when the first-alarm assignment arrived.

The only fire stream placed into service during the initial fire attack was a single 2½-inch handline, which was directed toward the outside fire escape to protect anyone using it. Unfortunately, this avenue of escape was cut off by the torrid blowtorch of flame, which would not diminish even under the well-directed stream of a large-bore nozzle.

On arrival, DFD Chief Perry Kirch took over command of the fireground and told Cosgrove to continue to direct the rescue efforts. Kirch ordered five master streams, two deck pipes, and numerous 2½-inch handlines be deployed to stem the onslaught of the fire.

All of the DFD’s engine companies pumped at the fire. Each engine’s hosebed was either empty or had just one or two hose lengths left on the wooden slats. Firefighters deployed more than 8,000 feet of hose and used steamer connections to pump water from hydrants several blocks away

War Veterans Join the Fight

A welcome blessing occurred when a couple dozen returning war veterans staying at nearby hotels volunteered their services to support the firefighters on the hoselines. Many had slept with their hotel windows open on that early summer night and were awakened by the sounds of the responding fire apparatus.

After the fire was extinguished, the firefighters were rotated in shifts to recover victims, which took approximately a week, since operating in the collapsed older section was quite hazardous.

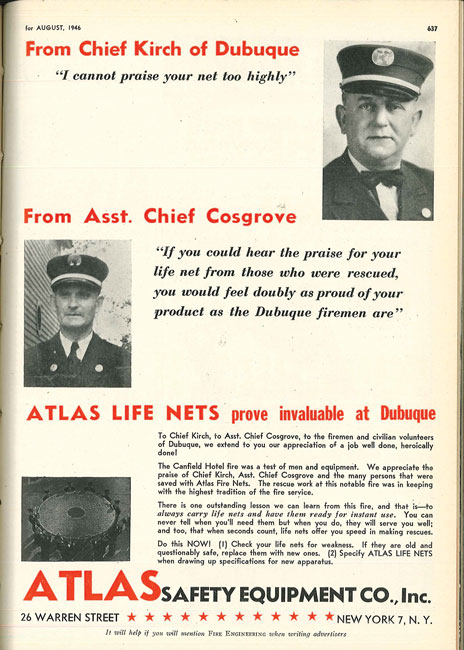

Afterward, DFD firefighters were held in high esteem and Cosgrove became a much-sought-after speaker at the early fire schools of the day. Notably, no other American fire department had ever deployed its life nets so intensely or attained the highest recorded number of rescued jumpers. This was the last time the fire department used the life net.

|

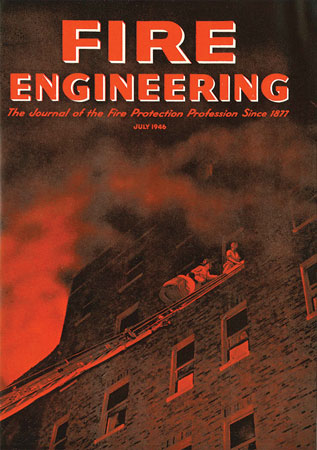

| (5) The cover of the July 1946 Fire Engineering depicts firefighters rescuing Hotel Canfield guests. The issue featured articles on that fire and on the one involving the LaSalle Hotel in Chicago, Illinois. |

Investigation

The Iowa state fire marshal and several investigative agencies found several principal factors that contributed overall to the rapid spread of the fire and consequent loss of life. A key factor was the original building’s open stairways, which allowed the smoke, heated gases, and flames to quickly ascend all floors. In direct combination with the very flammable fiberboard, the open stairways provided a wind tunnel effect for the flames to grow in intensity and rapidly transverse all areas of exposure.

Another factor was a piece of luggage that was propping a fire door open. It was discovered that a female victim tried to get out of the building the same way she came in. If all patrons had been instructed to use at least one other means of egress, the loss of life would have been greatly reduced.

In many of the hotel rooms where the doors and the transoms were closed, there was very little or no evidence of fire or smoke travel or damage.

Sadly, panic contributed to some deaths and severe injuries in both the older combustible and the newer fire-resistive sections of the hotel. People do not prepare themselves for emergencies when staying for any extended time in new surroundings.

In February 1947, William J. Canfield Jr., the president of the Canfield Hotel Corporation, announced that a full reconstruction would begin within two months and that the work would be completed approximately eight months later. The hotel would have a full fire sprinkler system and other alarm and fire safety devices installed.

The Hotel Canfield fire joined a long list of fatal hotel fires. Before the end of 1946, 119 people would perish in the Winecoff Hotel fire in Atlanta, Georgia.

|

| (6) Dubuque (IA) Fire Department officers testified to the life net’s role in saving lives at the fire in this August 1946 Fire Engineering advertisement. |

Fatal Fires Spur Action

The series of fatal hotel fires spurred officials to action. In January 1947, President Harry S. Truman called for a National Conference on Fire Prevention, which was held in May of that year. It urged federal, state, and municipal officials to take responsibility for fire safety in their jurisdictions and that the public support officials in enacting adequate laws for fire prevention and protection.

The conference’s Action Report recommended, among other things, the following: the use of fire-resistive building construction and finishing materials, the installation of fire barriers and fire doors, at least two independent and easily accessible fire exits, and improved fire codes and consistent enforcement. Other recommendations included improvements in firefighter selection, training, and education and in fire prevention and safety education for the public.

The International Association of Fire Chiefs, at its January 1947 meeting, recommended the installation of sprinklers or fire detection and alarm systems, the enclosure of stairways and elevator shafts, and the installation of fire division walls and doors.

Author’s note: Thanks to former Dubuque Firefighter Bill Hammel for his assistance in locating various historical documents and material for the preparation of this article.

MICHAEL L. KUK, Ph.D., CFO, FABCHS, FIFireE, is the retired chief for the Joint Readiness Training Center and United States Army Garrison at Fort Polk, Louisiana. A United States Army Vietnam veteran, he is chief fire chaplain for the Vernon Parish (LA) Fire Protection District and has more than 50 years of fire service experience and 40 years of chief officer tenure.

From the Fire Engineering Vault: Almost 50 Years Later, Gratitude for a Rescue

THE GREATEST INNOVATION IN THE FIRE SERVICE

October 1916 Fires

Fire Engineering Archives