The mental and physical stressors associated with the ever-increasing number of emergency responses are taking their toll on the health and well-being of America’s firefighters. A combination of acute and cumulative occupational stressors as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has contributed to a silent subculture of depression, isolation, mental fatigue, and apathy, often resulting in senseless premature deaths by suicide. Health and wellness initiatives for firefighters have been developed through collaborative efforts by nationally recognized fire service organizations, but too few of these programs have been implemented at the local level.

Risk Factors

Firefighting has historically topped lists of the “most dangerous occupations,” and rightfully so. Firefighting involves a high level of physical toughness and mental preparedness, paired with high intensity and stressful situations that necessitate rapid recovery in a tactical response scenario, which is often immediately dangerous to life or health. Today, the roles and responsibilities of firefighters include emergency medical services (EMS), which over the past few decades has emerged as the leading 911 response type for fire and emergency service providers.

Firefighters and emergency responders typically work lengthy shifts comprised of 12 to 24 hours and may experience high call volumes in a single tour of duty; mentally, physically, and emotionally stressful situations caused by severe trauma or loss of human life; insufficient and broken sleep patterns and insomnia; poor diet and overall nutrition; and virtually no opportunity for a routine exercise or workout regimen to combat this laundry list of risk factors. These largely modifiable personal health risk factors have culminated in the unexpected injury or death of an increasing number of firefighters and emergency responders at an early age and at an alarming rate.

Today, in comparison with the general population, substantially higher numbers of active-duty firefighters are dying from heart attacks secondary to cardiovascular disease (CVD) and occupational stress and suicides secondary to behavioral health disorders caused by chronic burnout, mental and physical stress and fatigue, depression, and PTSD.1 In a societal culture where health and wellness have become mainstream and trendy, fire and emergency service organizations are often missing the mark and lagging far behind, despite the glaring risk factors for firefighters and emergency responders.

Stress vs. Distress

The word “stress,” which comes from the ancient Latin language, means force, pressure, or strain. All of us have different levels of stress in our lives; some are actually essential and helpful (eustress) for leading a productive life. A certain amount of eustress increases positive challenge, motivation, awareness, and creativity. The thrill of responding to a challenging call or a fully burning structure is a source of eustress for responders.

On the other hand, distress is a negative aspect of stress that can be a destructive force in our personal and professional lives and eventually will impact our health, personalities, jobs, and family and other relationships. Left unchecked, distress eventually overwhelms our bodies mentally and physically; taxes our ability to cope successfully; and often leaves us feeling exhausted, hopeless, apathetic, and helpless.

Firefighters experience much higher occupational and physiological stressors at work in comparison to the average worker. Exposure to noise has been linked to hypertension, which is a common problem with firefighters. Station alarms and apparatus and train-style horns generate extremely high decibel levels. Other work-related factors that contribute to increased stress levels for firefighters include high occupational demands and low decisional latitude.2 Firefighters exposed to extreme stressors are susceptible to PTSD and severe depression.

Shift Work

Shift work is another important factor to consider when evaluating the impact of occupational stress on firefighters. A typical tour of duty (shift) for firefighters comprises 12 to 24 hours and may be extended with overtime shifts or mutual coverage for other firefighters. It’s not uncommon for many firefighters to work 72 to 96 hours straight without relief, which contributes to chronic sleep disruption and deprivation, psychological stress, and adverse metabolic and physiological changes.

Most Common Daily Stressors

The 15 most common daily stressors for emergency responders, according to the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS), are shown in Table 1. The scale was created in the late 1960s by Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe, University of Washington School of Medicine, to provide a standardized measure of the impact of a wide range of common stressors.

Much has been written on the benefits of healthy firefighters, most of which revolves around physical health. Firefighters must be physically capable and accustomed to handling stress, but mental health is equally important. Overexertion typically causes mental and physical mistakes. Consider that firefighters are the only professional athletes expected to work at peak performance without the opportunity to warm up. Few occupations stress the human body to the degree that firefighters experience in hostile and working fire environments.3

Incidents that necessitate firefighter peak performance can happen at a moment’s notice and at any time of the day. That critical call may come immediately after firefighters consume a large meal or are sleeping, hungry, or even physically tired and least capable of performing at their best. Situations like these lead to rapid overexertion of the human body and decreased performance of human cells, including brain cells. (3) The fire service cannot change the reality that incidents occur while firefighters sleep, are hungry, or are least capable of performing. However, the essence of being a professional firefighter is the ability to function safely at all times.

The following stressors have been identified as critical job-related stressors4:

- Long hours with excessive call volume coupled with little downtime.

- Low pay and benefits.

- 911 abuse.

- Dealing with dying patients, especially children, and their grieving loved ones.

- Dealing with major trauma and loss of human life.

- Personal risks to the responder’s life.

- Demanding physical labor under high-intensity situations.

- Guilt resulting from doubts about personal performance.

- Guilt after making a serious error.

- Responsibility for another person’s life.

- Limited training opportunities.

- Being expected to transition instantly from a state of rest to a state of peak performance.

- Interference with one’s personal or family plans.

- Poor work schedule (12- to 24-hour shifts).

Firefighters and EMS responders are expected to function in an inhospitable work environment where shifts are long and tiring, the work is demanding, and the emotional toll can run very high.

Sleep Deprivation

As noted above, sleep deprivation is a major contributing factor to occupational and physiological stress. Firefighters and emergency responders must be ready to respond to the needs of their communities 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and 365 days a year. Adequate rest and sleep periods are essential functions of human life and necessary to perform at an optimal level and live an otherwise healthy life. Sleep deprivation has been linked with increased errors in quick decision making, critical thinking, and poor judgment-skills firefighters need at their disposal at a moment’s notice.

When firefighters and emergency responders work long hours/shifts associated with chronic sleep deprivation, the end result may be an inability to think clearly and to make sound (and safe) decisions. These conditions typically bring forth feelings of irritability, stress, apathy, and depression. Chronic sleep deprivation is also a contributing factor in higher instances of cardiovascular disease and cancer, obesity, and chronic fatigue.5 Acute sleep deprivation is defined as less than four to six hours of sleep in a 24-hour period. (5) Fatigue is related to the interaction of physiological, cognitive, and emotional factors that result in slowed reactions; poor judgment; reduced cognitive function; and the inability to perform a task at a high, sustained level of accuracy or safety. (5)

Disrupted sleep patterns are a well-recognized source of occupational stress for firefighters. In a survey of more than 700 career firefighters who assessed a wide variety of common job stressors, almost one-third of the respondents said that a disrupted sleep pattern (disruption, poor quality of sleep, and deprivation) was an important cause of stress. (5)

Another study on occupational stress for firefighters used a biological marker to identify increased stress levels. It measured the level of serum cortisol, a hormone produced by the adrenal gland, which increases systemically in response to stress. (5) Elevated levels of serum cortisol have been associated with depression, fatigue, impaired memory, and autoimmune disorders. (5) In an independent study, when firefighters’ cortisol levels were assessed and evaluated at the beginning of the shift, individuals younger than the age of 45 had significantly higher levels of cortisol in comparison with the general population in the same age group. (5)

Study Conclusions

The summary below represents the conclusions of well-documented studies on the causal relationship between extended shifts/work hours and sleep deprivation for firefighters and emergency responders:

- Firefighters have documented increases in their risks for CVD, which may be precipitated by the chronic sleep deprivation associated with long shift hours worked. (5)

- Firefighters and emergency responders are at a high risk for decreased mental and physical performance levels caused by chronic sleep deprivation and long shift hours worked. (5)

- Fatigue among U.S. firefighters appears to correlate with the disproportionately higher number of fireground injuries sustained in the early morning hours. (5)

- Fatigue while driving apparatus has a causal relationship with the increase in the number of crashes that occur when driving following sleep deprivation or working long shift hours. (5)

Mental and behavioral health issues such as depression, increased apathy, dissociation with other department members, PTSD, and an increasing rate of suicides have highlighted the need for prevention and intervention strategies. Although there isn’t a wealth of empirical data on this health risk for firefighters, there is a general feeling among fire service and mental health professionals that behavioral health problems among firefighters and EMS responders may be widespread.

According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), studies have found that as many as 37 percent of firefighters may exhibit symptoms of PTSD.6 In 2013, the NFPA officially incorporated firefighter behavioral health issues into its national standards. Two chapters of NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, were retitled: “Chapter 11-Behavioral Health and Wellness Programs” and “Chapter 12-Occupational Exposure to Atypically Stressful Events.”7 To combat this growing epidemic in the fire service, prevention and intervention strategies focusing on alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and PTSD have been implemented in metropolitan fire departments across the country. Even still, behavioral health remains a difficult topic for emergency responders for a variety of reasons.

The fire service is a tradition-rich and proud profession whose members are commonly revered as heroes. A critical downfall of this reverence is that many firefighters often don’t recognize that they, too, can be the victims who may need assistance and intervention from their peers or medical professionals. Compounding the problem is the lingering stigma of the male-dominated, macho culture of the American fire service. Emergency responders take great pride in being a tightly knit brotherhood that works side by side in a variety of dangerous situations and environments, relying on each other for survival. This stigma can make it difficult for emergency responders to step outside of their comfort zone and acknowledge behavioral issues like depression, whether it’s their own or that of a coworker. (6) Some experts disagree that the issue of behavioral health problems among firefighters is growing. They contend that the only thing growing is awareness-the problem has been there all along.

Initiatives to Address Problem

To address this problem, the Jacksonville (FL) Fire and Rescue Department (JFRD) recently developed its first ever Behavioral Health Task Force (BHTF) and Peer Support Team (PST). The primary objective of the PST is to provide Stress First Aid (SFA) through prevention and intervention-to recognize the universal and early warning signs of firefighter burnout, fatigue, apathy, and depression and then intervene on the firefighter’s behalf before it’s too late. Based largely on the template of the National Fallen Firefighter Foundation’s (NFFF) Firefighter Life Safety Initiative #13, the PST offers flexible tools for addressing stress reactions in firefighters and other emergency responders. The primary function of the PST is to provide compassionate assistance to fire and EMS personnel, to prevent the progression of stress reactions, and to direct or refer affected individuals to more formal treatment when it is required.

|

| Copyright Statement: This work was prepared at the request of the U.S. Government. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a United States Government work as work prepared by a military service member, employee, or contractor of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties. |

Initiative #13 provides that firefighters and EMS responders and their families must have access to counseling and psychological support. A number of resource programs have been developed to assist providers of behavioral health therapies to acquire the latest in evidence-supported best practice skills through accessible, low-cost products developed by leading research and training programs in behavioral sciences and behavioral health.8

Stress First Aid (SFA)

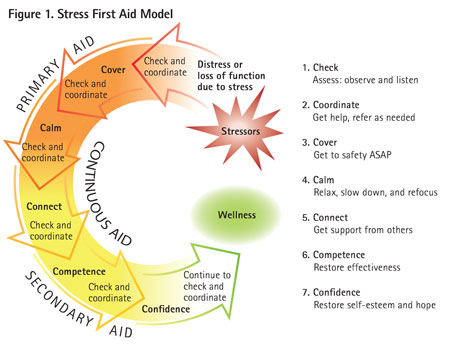

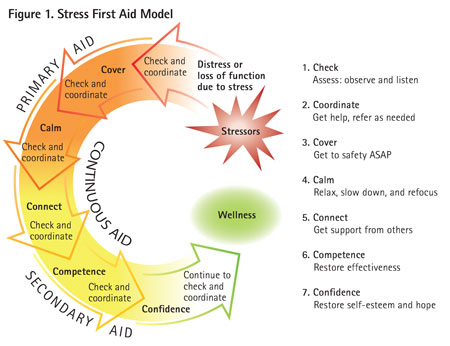

SFA, developed by the NFFF to combat fire service-related stress, consists of seven core actions: Check, Coordinate, Cover, Calm, Connect, Competence, and Confidence. Figure 1 provides an overview of the seven SFA actions and how they collectively work together to help ensure firefighter behavioral wellness. The goal of SFA is to determine how stress may be affecting an individual and to obtain for the individual the necessary level of care.

A complete overview of SFA is available at www.everyonegoeshome.com.

- Check. This SFA core action involves paying attention to fellow crew members and colleagues, noting persistent or significant changes in behavior that may indicate elevated stress levels. The check function essentially acts as a screening mechanism to determine if stressed individuals are properly recovering from a stress injury on their own (resiliency); whether they need the other preventive interventions of SFA; or whether they need higher levels of care. The check function can begin in the After-Action Review process.

- Coordinate. There are two broad goals for this function: (1) Inform those who need to know. At times, it will be necessary to advise key individuals who have a need to know, those who have the ability to provide help within the organization or provide emotional support; and (2) Obtain other sources of assistance or care. There will be times when an individual’s condition will necessitate a higher level of professional assistance that cannot be provided at the peer level. Movement to higher levels of care must be coordinated within the department’s capacity and sphere to offer assistance or to seek help outside the organization.

- Cover. This action is a natural extension of the fire service creed, “Every member of the fire department is responsible for their own safety and for that of their fellow crew members.” To cover is to reduce any immediate threats to safety that may result from an individual’s reactions to stress. This can mean simply moving an affected person from the scene of an emergency or a troubled/conflicted environment.

- Calm. This refers to slowing down and reducing stress reactions in the mind and the body, which also promote the recovery of normal mental and physical functioning. This can be accomplished through paying attention to how we speak to a stressed individual, how we listen empathically, and how we deliver information that is more neutral or positive.

- Connect. When some individuals experience an intense and stressful event or time in their lives, they may benefit from connecting with someone they trust and feel safe with, with whom they can talk about their experiences and perceptions of the event. The connect function is closely related to the foundation of mutual trust, respect, and fellowship that is common within the fire service.

- Competence. This action focuses on enhancing and restoring the loss of skills, abilities, and coping mechanisms that have been depleted or lost through stressful events. This action also lays a strong foundation for recovery and healing along with personal growth and development.

- Confidence. This step focuses on restoring an individual’s hope and rebuilding realistic self-esteem, both of which might have been significantly damaged in the wake of intense or prolonged stress. Confidence is the capstone of fully recovering from stress and becoming a stronger, more resilient, and more mature person as a result of the experience. The NFFF is providing a free online course on SFA and many of its other behavioral health programs. To access this material, visit www.fireherolearningnetwork.com.

Firefighter Suicides

In 2008, the Chicago (IL) Fire Department experienced seven firefighter suicides within an 18-month span. Similar patterns, known as suicide clusters, also occurred in Phoenix, Arizona; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and other large metropolitan fire departments. (6) The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) offers grant funding for supportive research and studies on firefighter suicides, the majority of which involve active-duty members. To address the need for empirical data, the NFFF has applied to the Assistance to Firefighter’s Grant Program administered by FEMA for funding to support research on firefighter suicides. (6)

A challenge in addressing behavioral health issues among emergency responders is quantifying the problem. Currently, no nationally recognized agency collects statistics on firefighter and emergency responder suicides. A recognized source for information on firefighter suicides is the Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance (FBHA.org), a nonprofit organization founded in 2011 by Jeff Dill, a captain with the Palatine (IL) Fire Protection District and a licensed counselor who specializes in firefighter behavioral health issues. According to statistical data compiled by Dill, 360 confirmed firefighter suicides occurred between 2000 and 2013, with 114 of those suicide deaths occurring in 2012 and 2013. (6) White males commit more than 70 percent of firefighter suicides. The majority of suicides are accomplished with firearms, followed by hanging. (6) The majority of firefighter suicides are among active-duty personnel. The information that Dill receives at FBHA.org is sent voluntarily and likely represents only a snapshot of the nation’s more than 30,000 career fire departments.

The nature of the roles and responsibilities for firefighters and emergency responders has dramatically changed in recent decades. Fire calls have declined, in part because of improved building codes and standards and fire prevention methods. This has necessitated that fire departments take on many new responsibilities such as EMS, motor vehicle extrications, hazardous materials management, and emergency preparedness. In 2014, the JFRD responded to 122,626 combined EMS and fire-related incidents. Of those, 107,628 were EMS related-88 percent of the total call volume; this is likely the case with most career fire departments across the country. First responders routinely encounter incidents that include severe injuries and loss of human life, including suicides.

Emergency responders face the horrific trauma of mass-casualty incidents and, more recently, emergency responders have become the target of active shooters. (6) There is no quick fix to the growing behavioral health problem in the American fire service. Negative stress left unchecked ultimately will adversely affect quality of life.9

September 11, 2001, took the focus on the behavioral health of emergency responders to new levels. The American fire service lost 343 firefighters on that fateful morning. Many firefighters and emergency responders watched helplessly as victims trapped by the flames raging through the World Trade Center towers jumped to their deaths. Responders were forced to search for the human remains of countless victims, including their fellow firefighters, in the rubble piles that remained after the twin towers and adjacent buildings collapsed. As a result of 9/11, the NFFF, through FEMA, developed prevention programs for PTSD, published many articles related to firefighter suicide, and developed two guides for fire chiefs and behavioral health professionals. For additional information, visit www.everonegoeshome.com.

Clearly, the fire service as a whole must change its attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (culture) toward firefighter behavioral health if positive changes and outcomes are to occur. The success or failure of this type of initiative is largely dependent on incorporating leadership, accountability, and personal responsibility into every practice, program, and policy related to firefighter behavioral health and wellness.

Endnotes

1. Firefighter fatalities in the United States. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/ff_fat13.pdf.

2. Federal firefighter presumptive liability. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.iaff.org/politics/legislative/Fedpresumptivefactsheet112.htm.

3. Dodson, D W. (2007). Fire Department Incident Safety Officer (2nd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Publishing.

4. Hawks, S & Hammond, R. (2004). Tackling stress management from all sides. Encinitas, CA: KGB Media, LLc.

5. Elliot, D & Kuehl, K. (2007). Effects of sleep deprivation on firefighters and EMS responders. Retrieved from http://www.iafc.org/files/progsSleep_

6. Wilmoth, JA. (May 2, 2014). “Trouble in mind,” NFPA Journal. Retrieved from http://www.nfpa.org/newsandpublications/nfpa-journal/2014/may-june-2014/features/special-report-firefighter-behavioral-health.

7. National Fire Protection Association: Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.nfpa.org/codes-and-standards.report-firefighter-behavioral-health.

8. National Fallen Firefighters Foundation (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.firehero.org.

9. Dill, J & Loew, C. (2012). Suicide in the fire and emergency services. Retrieved from http://firefighterveteran.com/images/stories/Nationla_Volunteer_Fire_Counsel/Firefighter%20suicide%20report.pdf.

DAVID S. CASTLEMAN is a 22-plus-year veteran of the fire service. He has served as the division chief of rescue for the Jacksonville (FL) Fire and Rescue Department since 2015. He is a member of the Fraternal Order of Fire Chiefs Association, the Florida Fire Chiefs Association, and the International Association of Firefighters. He has a BS degree in fire science administration from Waldorf University and a master’s of public administration from Anna Maria College.

Fire Engineering Archives