Chemical Protective Suits: In-House Maintenance

PROTECTIVE CLOTHING

Affectionately and unfortunately at times prophetically referred to as “mop and glow units,” hazardous material response teams are increasing in numbers throughout the country. But unless fully trained and properly equipped, personnel, as well as the environment they are attempting to protect, are in very real danger of suffering the effects of uncontrolled contaminants.

Experience has shown that hazardous material teams ideally should operate as separate units. Too many times, hazardous material incidents overlap other emergencies, causing delays, confusion, and inconsistencies. You can’t, in all good faith, put a man who has just come from a working fire in a chemical suit and expect him to operate at peak efficiency.

Under the “best” of circumstances, when you don a fully encapsulating suit, you are entering an alien environment. Your vision is limited, you have trouble walking, trouble handling items, you are hot, under stress, normally scared, and constantly aware that the next corner you turn might render your communications inoperable. Add to this the fact that you are carrying a minimum of 50 pounds of equipment, the suit, a (hopefully) one-hour self-contained breathing apparatus (which is NIOSH rated at a 45-minute working time and a 15-minute escape time, depending on the individual user, the working conditions, and the seasonal conditions), the over gloves, the over boots. and an explosion-proof portable light.

The hot zone of a hazardous material incident should be entered by a fully-equipped two-man team. A two-man backup team, also suited up, should be positioned in the warm zone. If operations take more than the approximate 20-minute working time, the backup team takes over and the initial entry team gets a full air cylinder and becomes the backup team. This expedites the mitigation and adds a margin of safety.

There should be a minimum of five operating personnel at any hazardous material incident. Working with fewer than this is inviting catastrophe and endangering the lives of all involved. One major city department operates with an eight-man crew at hazardous material incidents: one officer, a two-man entry team, a two-man backup team, a two-man decontamination team, and a resource or logistic supply man (the person responsible for getting information on the chemical involved and any needed assistance or equipment to mitigate the incident).

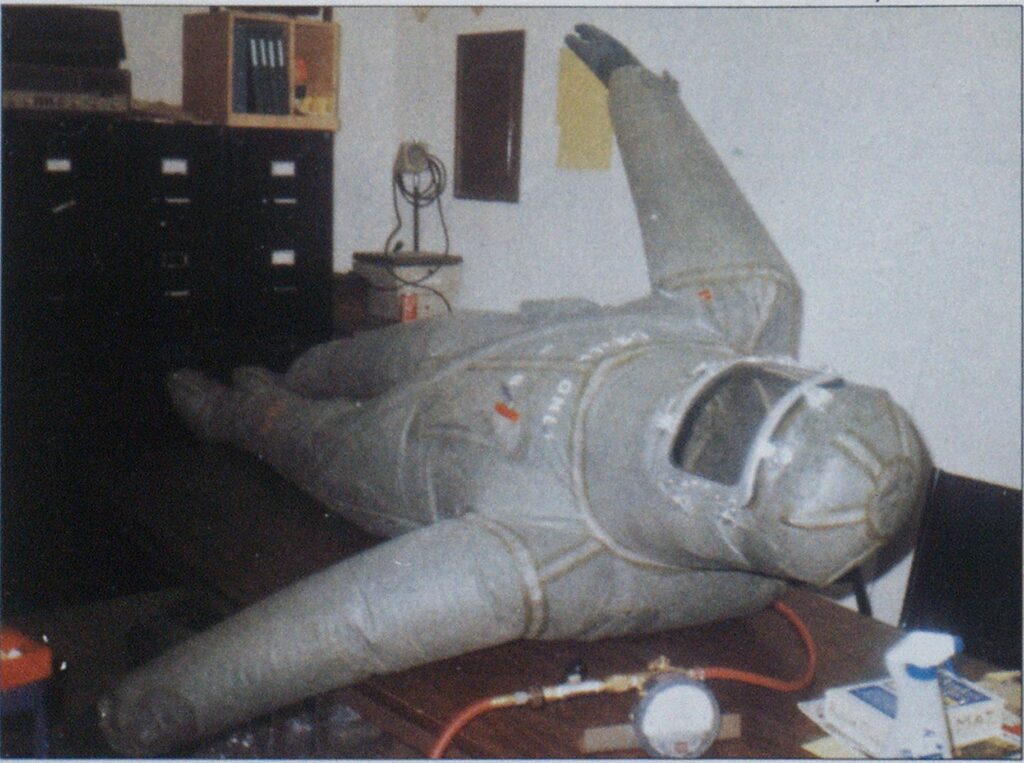

Another safety consideration is to use inflatable chemical protective suits. By inflating the suit with an air line, a purely visible positive inflation is seen, which protects the wearer from foreign atmospheres in case of punctures or small tears in the suit while operating. If during an incident all air supply systems fail, the suit is still holding five cubic feet of air, which gives you a few minutes of exit time before it has to vent to the outside atmosphere. Air normally supplied to a suit for inflation is not approved for breathing, but in an emergency, one must use his own judgement.

Photo by Arnold Merkitch

Of course, the drawback to a suit inflated with a separate air line rather than from the exhalation valve or positive-pressure mask, is that you are limited in distance depending on the length of the air hose, and you run the risk of snagging the dragging air line.

There are a variety of materials from which chemical protective suits are manufactured, butyl rubber, PVC (polyvinyl chloride), and a new Teflon suit is expected to be available within the year. I know you heard it before, but, again, you must obtain a sample of the suit material and test its durability and resistancy to the potential chemicals you might expect to encounter in your response district—before you encounter them.

If you are in a position where the order for your chemical suits will have to go up for bid, be extra certain of your specifications, and include in your specifications a manufacturer’s written warranty of at least 120 days as to the quality of workmanship, a delivery date, a repair clause, as well as specific “turnaround” time on suits sent away for repairs. This is because if you have a minimum inventory of suits and several are sent away for repairs, it could take from 60 to 90 days turnaround time; and if in the process a few more suits go out of service, you could be out of business.

A log book should be kept on each and every suit, including such information as the date it was bought, serial number, manufacturer, type of material, repairs made, what chemicals it was exposed to and on what date, operating time, results of inspection and testing after an incident, date returned to service, and any other information that you deem pertinent.

Some departments have their own trained personnel to do inspection and serviceability testing of hazardous material suits at regular intervals or after use and to make minor repairs to cut down on out-of-service time as well as the cost of shipping and repairs.

In our department, suits that have become contaminated are packed in a salvage drum, picked up and cleaned by a vendor, and returned to the hazardous material unit’s quarters. Suits are then washed again in our own commercial washer in the station, dried inside and out, tested, and, depending if repairs are needed, placed in or out of service.

Photo by Arnold Merkitch

Suits that are used at an incident but deemed by the hazardous materials officer not to be contaminated are returned to quarters where they are washed, dried, tested, and placed in or out of service.

We test/inspect the suits by placing them on a table, taping or plugging all the dump valves from inside, and closing all zippers. A magnehellic gauge with a six-inch water column is placed between the suit’s wall couplers and an incoming air supply. A magnehellic gauge is easily readable and can be depended on to note changes at very small pressures.

When a reading of 2.5-inches on the water column is attained (which is approximately 1/10 psi), the suit will be fully inflated, arms outstretched. The air source is then closed. If the water column drops more than 20% after three minutes, a leak is indicated and a soapy water solution is sprayed or brushed on the suit. The leak will “bubble up.” The leak area is then dried and marked (with chalk), repaired, and re-tested.

When air is first fed into the suit, the suit’s physical appearance will change, i.e., arms inflating then collapsing. Nine out of ten times, this is caused by the air moving inside the suit. Wait approximately one minute until the air stabilizes before taking a true reading.

This procedure is being tested at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California at the request of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and will be presented to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) to standardize testing in the United States. Several suit manufacturers also use this testing procedure in varying degrees. (For a more complete discussion on methods of suit inspections, see “Exposure Suit Inspection Procedures,” FIRE ENGINEERING, February 1985.)

Here are a few preventive maintenance tips on caring for and preserving the integrity of your chemical protective suit:

- If you have suits that are equipped with couplers for use with umbilical, positive-pressure, air supply lines, the couplers should be at right angles to the suit and canted toward the front of the suit so that the air line can be slung over your shoulder and held with one hand when walking. This way, in case of a snag, the air line will not pull directly on the suit and cause possible damage.

- All fittings applied to suits should be brass or of another noncorrosive, spark-proof material other than plastic. Cleaning, either in-house or by a vendor, exposes fittings to water and eventually rusting and possible failure.

- Viewers or visors on suits should be equipped with easily removable, compatible, clear coverings so that in case of contamination and clouding or “milking,” the outside cover can easily be removed and an exit made safely.

- No powders are to be used on the interior of the suit. When exterior gloves are powdered for easy use of two pairs of gloves, the zipper on the suit must be fully closed while in storage so as not to contaminate the interior of the suit.

- Suits should be permanently marked on the interior with the manufacturer’s serial number, and numbered on the exterior with a hazardous material unit number for easy identification and communication at incidents. All detachable items on the suit should be marked with the serial number of that particular suit so that a com-

- Suits should not be dropped or dragged. This action constitutes the major cause of minor repairs on suits.

- When washing suits in quarters, anything that is easily detachable should be detached and washed by hand. If left on the suit, these items will work themselves free in the wash and may damage the suit in the process.

- Suits that are washed in quarters should be turned inside out when placed in the washer. Frequently, when suits are returned from the vendor after decontamination, caustic soap residue is visible on the interior of the suit, and some people with sensitive skin could develop a reaction. Also, an odor develops from perspiration.

- Suits should be dried inside out first. Only after the inside is dry should the suit be turned right side out for drying.

Photo by Arnold Merkitch

plete suit will stay together through its life cycle.

After this, the suit is then ready for testing and, if the inspection is successful, storage.