AEROMEXICO PLANE CRASH Cerritos, California

IT was just before noon on August 31, 1986, when several frantic civilians arrived at a Santa Fe Springs, CA, fire station with confused descriptions of a disaster that had just occurred. Although the specifics were obscure, it was clear that there had been some sort of plane crash in the south end of the district.

As Engine 83 began to roll toward the direction indicated, a plume of gray-black smoke could be seen pushing skyward. By this time, other reports of the incident were coming over the fire radio. While additional units were being dispatched, the Santa Fe Springs firefighters discovered that the crash site was in the vicinity of Carmenita Road and Ashworth Place in the City of Cerritos (see map).

Although this area is protected by the Los Angeles County Fire Department, the existing mutual aid agreements call for not only Santa Fe Springs, but the Orange County and Buena Park Fire Departments to respond as well.

Los Angeles County Assistant Chief Steven Sherrill, who was the initial incident commander, set up a command post on Carmenita Road and instituted the incident command system to direct arriving units to specific locations. In this way, specific physical or geographical sections (known as divisions) are established within which assigned officers and companies operate and provide reports to the incident commander.

At approximately the same time, Santa Fe Springs Battalion Chief Norbert Schnabel arrived on the scene and was given command of the northern sector of the incident. Chief Schnabel instructed Engine 83 to take up a position on Ashworth Place, which appeared to be the northern perimeter of the incident.

As Chief Schnabel surveyed the scene, he was converged upon by dozens of hysterical residents. He attempted to decipher useful information from the civilians who were alternately pleading and insisting that he search for their families or protect their homes.

According to Chief Schnabel, the neighborhood appeared to have been rocked by a “major explosion”; it did not initially look like a plane crash since there were “few parts of the plane that were recognizable.” The area of impact had begun to burn with such intensity that it had actually created a small firestorm.

The initial strategy was defensive and called for protecting the exposures that surrounded the major area of devastation. Under the direction of Acting Captain Jim Hart, Engine 83 laid a 5-inch supply line from a hydrant at the corner of Ashworth Place and Holmes Avenue. They also set up a master stream operation as three other engines arrived at the scene.

As the incident escalated to a third-alarm structural assignment, the number of paramedic squads and support units that were requested was above and beyond that which is ordinarily dispatched. As the medical units arrived on the scene, it quickly became evident that an elaborate triage system would not be needed, since most of the crash victims had been killed upon impact. The few individuals who did require treatment were swiftly transported to nearby medical facilities.

In addition to the 53 units already on the scene, Chief Sherrill also requested that two strike teams be put on standby in anticipation of the need for manpower in dealing with the disaster. These teams each consist of 5 engines, 20 firefighters, and a battalion chief.

Information relating to the details of the incident had now begun to filter into the scene. Witnesses who had seen the events that led up to the crash said that a small private plane struck a commercial airliner causing damage to both planes. These witnesses were taken aside by sheriff’s deputies in anticipation of the investigation that would be conducted by the National Transportation Safety Board.

As ambulances assembled in a staging area near the command post on Carmenita Road, firefighters continued to battle the adjacent blazes. With large quantities of jet fuel scattered over the several block area of the crash, firefighters not only had structure fires to contend with, but also burning flammable liquid on lawns, sidewalks, and in driveways. However, since most of the liquid was spread out over a large area, the fuel was quickly consumed, thus eliminating the need for the foam units that had been requested.

Hundreds of spectators gathered as close to the scene as they could get. Under the direction of Chief Sherrill, sheriff’s deputies and police officers from neighboring agencies established perimeter control boundaries to limit access to the disaster area and provided a traffic corridor for arriving emergency equipment and personnel.

Unlike the September 1978 crash of a Pacific Southwest Airline jet and a light plane in San Diego, CA, where narrow residential streets made access difficult, Los Angeles County units had no trouble reaching their destination.

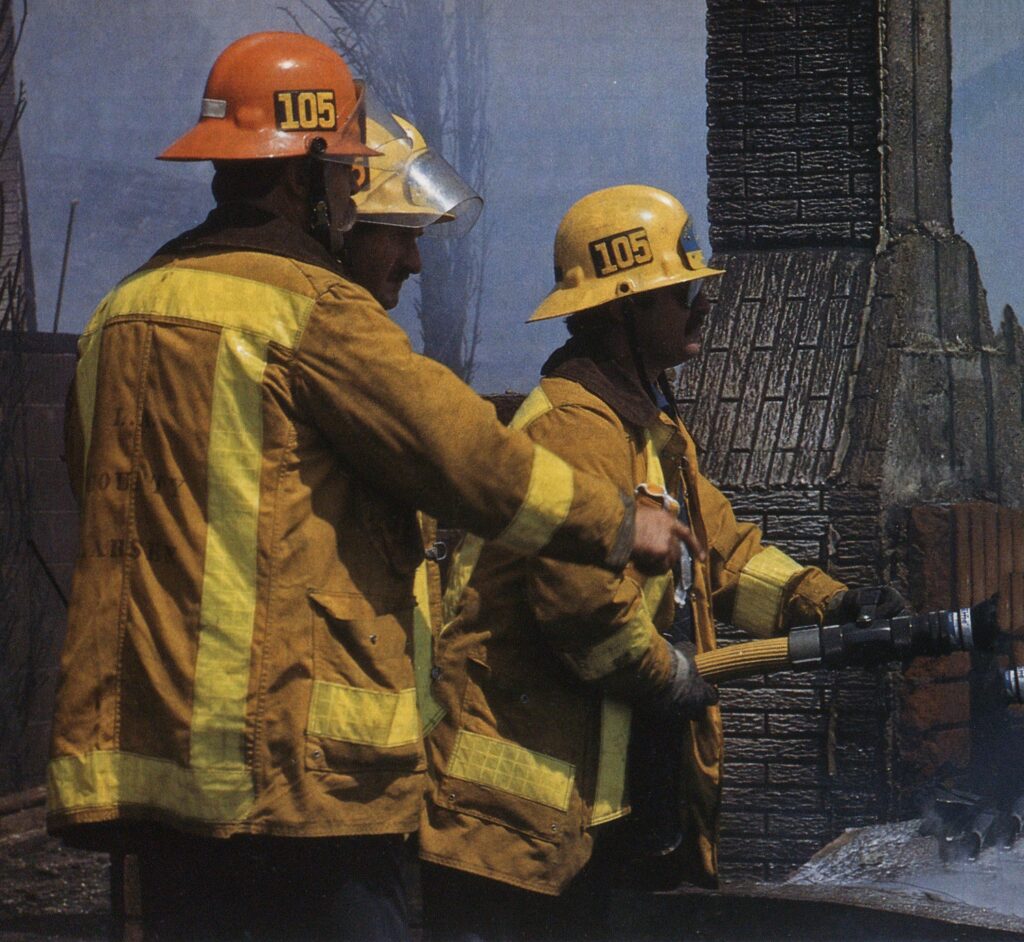

Photo by Edward Sherman

Since Carmenita Road permitted direct access to the scene, and is a main north/south road, incoming units were able to stage in one area and still leave a path open for other vehicles.

Another asset to the firefighting effort was the fact that the water pressure in the area remained sufficient throughout the incident. Despite the use of three master streams and numerous handlines, firefighters did not experience any difficulty in maintaining sufficient water supply.

Upon arriving on the scene, Los Angeles County Deputy Chief Paul C. Delaney assumed the role of incident commander. He was informed that the main body of fire had been substantially controlled, but that many smaller pockets of fire continued to burn, some of which were fueled by initially uncontrollable natural gas leaks.

As more sheriff’s deputies moved into the area, residents of the damaged homes were evacuated. The news media, who were arriving in large numbers, were given only limited access to the area so that they would not impede the emergency operations nor disturb the evidence of the crash.

The light plane, which was being protected by sheriff’s deputies, had crashed some three blocks away from the commercial airliner on a baseball field at Cerritos Elementary School. This plane, identified as a Piper PA-28 monoplane, was essentially intact except for the cockpit which had been sheared off. The three occupants, two adults and one child, had been decapitated at the time of the collision. The Piper had not caused injury to any persons on the ground, and it did not require any firefighting efforts.

As more information was channeled to the command post, it was learned that the commercial airliner had been an Aeromexico DC-9 en route to Los Angeles International Airport. The flight, number 498, had initially left Mexico City with stopovers in Guadalajara, Loreto, and Tijuana. Aeromexico officials informed authorities that 58 passengers and 6 crew members were believed to have been aboard the aircraft.

Concern was not only for those victims aboard the planes, but also for the unknown number of fatalities on the ground. One house posed particular concern since there were numerous vehicles in the driveway. It was believed that a party had been in progress at the time of the crash. This particular house, at the corner of Holmes Avenue and Reva Circle, was among the worst devastated in the sixblock area of the crash.

With hundred of requests pouring in about the welfare of other residents of the area, the Red Cross quickly set up a temporary post in a nearby building where information could be exchanged.

While the firefighting effort continued in the area of the crash, Chief Delaney realized that the emphasis would soon shift from extinguishment to the massive job of overhaul. One of the two strike teams on standby was called to the scene to relieve weary firefighters; the other strike team was released.

The job that laid ahead for firefighters was an arduous one. Not only would they be expected to work their way through thousands of pounds of debris, but also locate and cover the numerous body parts entangled in the wreckage. Although paramedics had been unsuccessful in their primary search for survivors, they still moved about among the charred metal looking for any signs of life.

Despite the fact that 16 homes were damaged, of which 9 were totally destroyed, it was miraculous that there hadn’t been more loss of life and property. (At presstime, approximately 82 lives were reported lost in the incident.) Even though most fire departments plan and rehearse the details of a disaster operation, it is still difficult to predict the outcome of an actual situation. However, at this particular incident, the training and leadership skills of the area agencies proved to be a clear asset to the community.

Since all of the agencies involved in the crash were part of the Los Angeles County automatic mutual aid agreement, and were accustomed to interacting with one another on a daily basis, the high level of cooperation allowed a smooth overall operation. Several common radio channels simplified the exchange of information and reduced the duplication of efforts which frequently occurs at multi-agency incidents in some areas.

Photos by Edward Sherman

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS

In this air tragedy in Los Angeles, just as in the 1978 San Diego crash, a private plane and a commercial airliner collided on a clear day when there was nothing that seemed to interfere with either pilots’ vision.

Both crashes occurred in residential neighborhoods with similar geographic and demographic features and destroyed approximately the same number of structures (14 homes in the North Park section of San Diego, and 16 homes in the Cerritos section of Los Angeles County).

In North Park, as in Cerritos, emergency personnel were faced with the frustration of not being able to aid or rescue the majority of the victims of the crash. This fact, coupled with the task of having to locate, mark, and sometimes retrieve hundreds of body parts was sufficient to effect the mental health of most public safety workers in some way. According to Marguarite Jordan, Health Programs Coordinator for the Los Angeles County Fire Department, this realization came at a later stage in the San Diego incident than it did in Los Angeles County.

In 1978, the awareness of syndromes such as post-traumatic stress disorder were not found in the medical literature as commonly as they are today. Psychologists and other mental health professionals were aware of the symptoms in the 1970s, but they were still putting together pieces of a broadening disorder that was often associated with the veterans returning home from Vietnam. Since much of the research was still in its early phases, there were few if any public safety agencies that were adequately prepared to deal with the needs of their employees six or eight years ago.

According to Ms. Jordan, the need for immediate intervention is clearly in the minds of today’s fire administrators.

In order to prevent latent or prolonged emotional disturbances as were reported by police and firefighters after the San Diego incident, each emergency responder at the Cerritos crash was required to leave the scene by way of a specific station where three psychologists, one chaplain, and the health programs coordinator were in attendance. In this way, it was certain that all personnel would receive at least an initial session of counseling with a professional.

Emergency reponders were told to expect certain post-traumatic stress symptoms, the initial ones being anxiety, apprehension, frustration, and irritability. As time passes, depression, feelings of isolation, loss of appetite, and phobias could also result.

In order to prevent or reduce the severity of these symptoms, the County of Los Angeles enlisted the assistance of Dr. Jeffrey T. Mitchell and other professionals skilled in crisis counseling. Many psychologists within the community also volunteered their time to assist in the counseling process.

Through the steps taken by the Los Angeles County Fire Department and other fire agencies, not only was the possible loss of productivity and early retirement reduced, but a genuine concern for the well-being of the emergency responders was also displayed.

The Cerritos crash, like many other disasters, resulted in the tragic loss of life and property. But it was other similar incidents in the past that prompted Los Angeles area fire agencies to prepare and train for just such an event.

It can only be hoped that the Cerritos incident might stimulate discussion and preplanning within other fire departments and public agencies throughout the country so that the lives of the victims would not be lost in vain.