Article and photos by Raul Angulo

I’m noticing a disturbing trend that, on the surface, doesn’t seem like a big deal, but I’m not sure if everyone has thought this practice through. I’m talking about firefighters who use a leather radio strap and holster to carry their portable radio under their bunker coat during firefighting operations. I’m suggesting that firefighters who carry their radios like this have never been pinned down.

When I joined the fire department back in 1978, only the officers had portable radios. Today, every firefighter has a portable radio assigned to them for the shift. With the radios came the modifications to the bunker coats. Every modern fire coat has a special breast pocket for the portable radio. It’s hard to find a bunker coat without one.

The leather radio strap, made popular by the firefighters in New York and Boston, has finally gained popularity in West coast fire departments, including Seattle. Let me start by saying I have a leather New York radio strap that goes over the shoulder and across my chest, and I make good use of it – EMS calls, building inspections, and training exercises that don’t require full structural firefighting personal protective equipment (PPE). The radio strap is an excellent accessory for these activities because the alternative is to wear it on a belt clip. The radio and the belt clip can add considerable weight to the belt, so unless you buckle your belt tightly, it has a tendency to make your pants sag – at least it did with me! (I don’t know how the cops can wear all that gear around their waist and keep their pants up.) I knew I had to find a better way to carry my radio and opted for the leather strap, but wearing it under my bunker coat just didn’t seem like a good idea – I don’t understand why this trend is gaining popularity. This practice draws a red flag for me because I can immediately think of numerous scenarios where the placement of the radio under the coat can be problematic and even detrimental. What’s my concern here? Firefighter survival – I want you to have every available option to transmit a Mayday and survive the event!

- Firefighter Basics: Calling the Mayday

- Training Minutes: Calling the Mayday

- Handling the Mayday: The Fire Dispatcher’s Crucial Role

- Walton: Mayday, Mayday, Mayday…

Let’s look at some valid reasons given for wearing the radio strap under the bunker coat:

- The radio unit is protected under the protective layers of the bunker coat from thermal assault, heat, smoke, water, impact, getting bumped, or falling out of the pocket.

- The microphone (mic) cord is run up inside the coat and exits out the collar or through the top snap/fastener area. The mic hangs loose or is clipped to the chest strap of the SCBA. This protects the mic cord from the fire environment, being severed, and from getting caught on objects.

- Based on some manufacturers’ recommendations, wearing the radio and antenna on the hip is better for transmission and reception of communications, though I have not noticed a problem transmitting or receiving radio messages by carrying my radio in the breast coat pocket.

Let me correct some misinformation and assumptions that are out there and address the reasons this is not the best way to carry a portable radio when engaging in structural firefighting. Under normal circumstances, carrying the radio under the bunker coat will not present a problem. Ninety-nine percent of the time you’ll be able to operate your radio and never give it another thought. Even if you get lost, disoriented, or trapped in a room, you’ll still be able to reach your radio. But if that one percent is an incident where you’re trapped—or, more specifically, physically pinned down or entangled where the movement of your arms and hands are restricted–you’re going to get jammed up. Keep in mind that in the worst case scenarios, you’re going to fall through a floor or a roof, or a wall or ceiling will fall on top of you.

Firefighting consists of many physical tasks. Conducting searches, advancing hoselines, carrying ladders, cutting roofs, and pulling ceilings involve a lot of twisting, crawling, turning, bumping, sliding, etc. If your radio is under your coat, you could accidentally loosen the antenna or change the channel without even knowing it. I’ve had this happen to me using the radio pocket, so I know it happens. Be honest – you know this happens. One indication you’re on the wrong channel is a sudden absence of radio traffic on the fire channel. At the Blackstock Fire, one of Seattle’s line-of-duty deaths in 1989, Lieutenant Matthew Johnson was accidentally on the wrong radio channel – a factor in the incident. Newer radios have a computerized voice that announces the selected channel over the speaker when the knob is switched, but not all portable radios have this feature. If you need to adjust the volume or switch channels, you need to do this on the main radio unit – if you can reach it.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Another problem we run into with portable 800 MHz radios is when firefighters enter large high-rise buildings or substantial structures with lots steel and concrete. Once crews are inside or in below-grade levels like parking garages, the repeater signal is lost and the radios “bonk.” The solution is to switch to the simplex channel (radio-to-radio) by operating the rocker switch on the main radio unit – if you can reach it.

Newer radio models have the emergency button, channel selector, and volume control knobs integrated into the hand mic, giving the firefighter better communication options. But many fire departments still use the basic hand mic that simply keys the radio; however, all the features are rendered useless if the cord breaks or is severed. It sounds like I’m making an argument for the radio strap… not quite. Firefighters who run the mic cord up under the coat claim that in addition to protecting the cord, if the cord is severed, it would lead to an “open mic” or open channel, preventing the firefighter from transmitting or receiving a radio message. Not so. According to Motorola, if the cord is severed, it simply renders the mic and the speaker useless. The wires left within the cord would have to be touching just right in order to hold the channel open. It is highly unlikely that this would happen. Besides, many Motorola radios are equipped with a feature that detects when the mic cord breaks or is separated from the radio unit. After a few minutes the mic speaker will default back to the radio unit speaker – if you can hear it from under your coat.

I teach my rookies and crew members that the mic cord is their lifeline when they get in trouble so it needs to be protected. That’s why you don’t want to drape the cord over your shoulders and around the back of the coat collar. The mic cords are optimal in temperatures up to 140°F (60°C) – flashovers can be well above 800°F (427°C). If you’re caught in a flashover (and survive), chances are you’ll be prostrate, face down. That puts your mic cord at the most exposed part of your body – the shoulders and the neck. There are case studies where the mic cord has burned off from the radio. Wearing the mic cord over the shoulders and collar is another practice that should be avoided.

Though burning a mic cord off from the radio or accidentally severing it is a possibility, it’s a rare occurrence. What breaks more frequently is the connecting unit and bracket that attaches the mic cord to the actual radio. This plastic unit slides into a small groove and is held to the radio by a rocker clip and a small set screw. The impact force from dropping the radio or accidentally whacking it on this connector can shear it off the bracket. Once the electronic contact heads are separated from the radio, it renders the entire mic cord useless, no matter what features are incorporated into the microphone.

In this case, there are three more ways to transmit a Mayday or radio message over the radio.

1. Simply depress the side panel key button and speak into the radio. You don’t even have to remove the radio from a pocket or holster. You can key the button right through the pocket – if you can reach it.

2. When the radio “bonks” because of signal interference, switch to the simplex channel and call for help – if you can reach it.

3. Press your emergency button on top of the radio. This will transmit the radio identification number and the name of the firefighter logged on to the radio to the fire alarm center. It will also automatically switch the radio to the designated Mayday channel – if you can reach it.

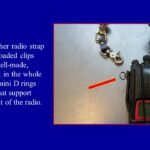

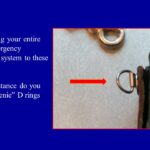

Finally, take a look at the radio strap and the holster. The radio straps usually have heavy-duty, spring-loaded clips, but the weakest point in the whole system are the two small D rings on the radio holster. These are where the radio strap clips are typically attached to – how much resistance do you think these “weenie” D rings can withstand? The D ring on the back of your fire helmet is beefier than these little pixies, and that’s just for hanging your helmet in your locker. We’re talking about supporting the entire weight of your radio under extreme physical activity! What’s the condition and thickness of the leather holster where the D rings are attached? You are entrusting your entire emergency communication system – your lifeline – to these mini D rings.

Case Studies

Above is a short video clip of a firefighter falling through a roof during vertical ventilation. He manages to arrest his fall but his lower torso is inside the burning attic space. His partner immediately helps pull him out of the hole and back onto the roof. Points for discussion:

- If assistance was delayed and if his radio was under his coat at waist level, and if his mic cord was damaged, would he be able to reach his radio and activate his emergency button?

- The radio would also be subjected to temperatures well above 500°F. Our bunking gear is only rated for temperatures up to 500°, so the entire radio unit is at risk of failure regardless of how the mic cord is worn.

- If the radio was carried in the breast pocket, it would still be protected.

- The firefighter is using his arms and hands to keep himself from falling into the burning attic. If he was pinned down or wedged in, he would still be able to utilize all the features on his radio, including his emergency button if it was carried in a breast pocket. He’s certainly not going to hold himself up with one hand so he can fumble around the burning attic space to operate his radio with the other hand.

VIEW SLIDES >>

On October 29, 2000, Los Angeles County (CA) Fire Captain Gary Morgan fell through the floor at a commercial structure fire. The illustrations depict how Captain Morgan ended up. He was wedged in the floor like a lobster trap. He sustained severe thermal burn to his legs, back, and torso. Captain Morgan was eventually rescued by the rapid intervention group and survived the event. After a long rehab, Captain Morgan returned to his company and finished out his career. Points of discussion:

- If Captain Morgan carried his radio under his coat at waist level, he would not be able to reach it or depress his emergency button.

- The portable radio would have been subjected to the same thermal assault that the captain’s lower extremities and torso were. This could have led to total radio failure regardless of how the mic cord was carried.

- Initially, the captain still had use of his arms and hands. His radio was actually carried in the left breast radio pocket. He would have the ability to depress his emergency button, raise the volume, change channels, key the mic or the hand set, and change to a simplex channel.

- The captain’s face piece was knocked off. He was in and out of consciousness and suffering the effects of smoke inhalation and carbon monoxide. Perhaps all a firefighter can do in this state is press his emergency button – if he can reach it

Protecting the Box

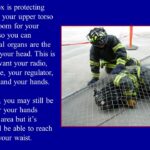

If you trip, one’s natural instinct is to put both arms out in front of you to break your fall and protect yourself. We need to teach firefighters to try and “protect the box” when they fall. Protecting the box is keeping a space around your face so you can move your head, see, and create a space large enough so your chest can expand, allowing you to breathe. It also allows you some hand movement so you can reach your mic or the portable radio unit, transmit a Mayday, press your emergency button, check your air supply, operate the bypass valve on your SCBA regulator, activate your PASS device , and turn on your flashlights.

The five positions for protecting the box are:

- On hands and knees crawl position. The strongest position – you can support a tremendous amount of weight in this position.

- Locking your elbows and supporting weight on the humerus bones.

- Semi- push-up position with knees on the ground.

- On your side.

- On your back supporting the weight with your hands and elbows (Military press position).

Back in 2010, at a vacant warehouse fire, an exterior wall fell on top of Seattle Fire Lieutenant William Elleby, crushing him. He went to pull back a knucklehead firefighter who was operating inside the collapse zone. The firefighter made it out but Lt. Elleby did not. Fortunately, other crews were close by and rushed to his rescue. This group effort was successful in lifting the heavy wall off Lt. Elleby, and he survived the event by crawling out from underneath the wall. He suffered a concussion, crushed tissue injuries, and a severe ankle fracture separating his foot from his leg.

I asked Elleby during his recovery if he was able to reach his radio to call a Mayday. He said, “Cap, I wasn’t thinking about anything except trying to breathe! I couldn’t breathe! That wall was so heavy, it just crushed my chest and even though I had air in my SCBA cylinder, I couldn’t expand my lungs to breathe. I needed air and was starting to panic. As soon as the guys lifted the wall and I saw some daylight, I was able to take a breath and I bolted out from under there!”

I asked his opinion on wearing the radio strap under the coat. He said, “If I was just pinned and able to breathe, there is still no way I would have been able to reach my radio and fire my emergency button!”

Teach your crews if at all possible, they need to protect the box. You want every piece of survival equipment within that box because that is where your vital organs are and that’s where your hands are.

*

I’m sure that for every scenario I cited here, proponents of the radio strap can offer counter scenarios. But after hours of research, practice, and actual emergency incidents, I’m convinced “in the pocket” is the best way to carry a portable radio. I had a training instructor tell me his rookies were having trouble with their radios falling out of the pockets during training and the repairs were getting expensive so they implemented the use of radio straps. This is the wrong solution to that problem. The Velcro flaps that cover the radio pocket are sufficiently strong enough to hold portable radios if they are properly secured. I’m not seeing portable radios falling out of pockets on the fireground. My guess is a rookie who is losing his radio isn’t securely closing the flap.

A firefighter has to be able to reach the hand mic, the radio, key the radio, push the emergency button, increase or decrease volume, change channels, switch to simplex, and tighten down a loose antenna. If you become pinned down using a radio strap under the coat with a standard mic cord, you’re settling for just one method of calling a Mayday when you actually have four methods available to you. It’s my opinion that if you’re a training officer or a chief of a training academy teaching this method as the way new firefighters should carry their radio during firefighting operations, you’re doing them a disservice, limiting their emergency communication options, and setting them up for failure. That’s a polite way of saying “What are you thinking?! This is crazy!”

RELATED: Drills You Won’t Find In the Books: The Fence Drill

When it comes to personal preferences, firefighters are stubborn, so we’re not going to settle the issue here. You’re going to have to go through The Fence Drill to settle it—it may cause many firefighters to think twice and abandon this practice altogether.

- Q & A: Raul Angulo on Drills You Won’t Find in the Books

- Drills You Won’t Find in the Books: Roll-Up Doors–In or Out?

- Drills You Won’t Find in the Books: Elevator and Stairwell identification Drill

- Tiller Tape, Stripes, Markers, and Other Clever Uses for Tape

RAUL A. ANGULO is a 37-year veteran and captain of Ladder Co. 6 with the Seattle (WA) Fire Department. He is an international author and instructor on various fire service subjects including strategy and tactics with firefighter accountability, crew development, and company officer leadership. He writes the monthly column “Tool Tech” for Fire Apparatus and Emergency Equipment magazine.