BY CASEY McCASLIN

It was setting up to be a busy morning. A major wreck on the highway was already tying up most of the city’s fire and emergency medical services (EMS) resources. Truck 2’s officer, Captain Jones; Driver Smith; and Firefighter Cruz were having their morning briefing when the emergency alert tones sounded. It was a medical call only a few minutes from the station. Normally, this would be a routine medical call, but Station 2’s mobile intensive care unit (MICU) was assigned to the wreck. The only available MICU was at Station 5, all the way across town. Jones knew Truck 2’s crew would be on scene for several minutes before the MICU arrived. As Jones was thinking to himself, “Let this be a minor call,” dispatch came across the radio and reported that cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was in progress.

What happened next was an organized plan of action. Truck 2’s three-person crew knew exactly what role they were about to perform. There was no discussion about assignments and not a hint of chaos. Each crew member knew which pieces of equipment to grab and where to position themselves according to the patient. Jones started CPR, Smith began ventilating the patient and preparing the intubation equipment, and Cruz placed the patient on the pacer pads and four-lead electrocardiogram (EKG) before starting an intravenous (IV). By the time the MICU arrived three and half minutes later, the patient was intubated and the first round of medications had been administered. The two-person MICU crew knew their roles and had the patient prepped and en route to the hospital within a few minutes.

What made this CPR so smooth? There was an organized plan in place before the call occurred. Each member of the crew, Truck 2, and the MICU knew their roles and responsibilities before they arrived on scene; this allowed them to function as an organized team. Having a plan in place before the call occurred allowed them to gain control of the scene and function in an efficient manner.

Not all medical calls run so smoothly. We have all been on medical calls where nothing goes right. You cannot get an IV, three people are fighting over who is going to intubate-oops, how long has the patient been in that rhythm? Is anyone bagging the patient? Someone took every medical bag and dumped all the contents on the ground so no one could find anything. The only thing you can depend on is chaos. We have all been there.

What is the difference between the two scenarios? Jones and his crew had an organized plan of action in place before they left the station. They knew their assignments, which pieces of equipment to grab, and where to position themselves around the patient. All these steps created an efficient process for delivering patient care. There was no discussion of who was going to intubate or start the IV. They arrived on scene and went to work.

We work in a fire-based EMS industry. But, when was the last time anyone sat down and thought about how we organize EMS calls? For instance, have you ever thought about bag placement? Can such a simple act really make a significant difference in how efficient and organized the call is? Absolutely! Placing the airway bag at the patient’s feet means that for every piece of equipment we need from that bag, we have to serpentine back and forth through a handful of other medics trying to complete important tasks; this just adds unnecessary chaos to the scene. Seems fairly simple, right? Yet, how often do we conduct training on organizing EMS calls? The answer is probably rarely to never. We do a very poor job of truly analyzing the organization and efficiency of medical calls. Training is conducted on basic general medical knowledge and department-specific protocols, but a great opportunity is missed to improve the organization and efficiency on EMS calls.

Fire-based EMS organizations spend numerous hours and resources attempting to improve emergency scene organization and efficiency on fire and rescue emergencies. Unfortunately, the time and resources spent do not apply to EMS calls. The main focus on improving scene organization and efficiency only applies to fire and rescue operations, even though EMS calls represent the greatest call volume for fire-based organizations. We spend most of our time on the chest pains, shortness of breath, strokes, seizures, and such.

Standard Plan

The Allen (TX) Fire Department (AFD) undertook a holistic analysis of how it organizes EMS calls. What we realized was that, like in so many other departments, there was no consistent scene organization. Each officer on scene decides how each EMS call will be organized. Similar EMS incidents vary significantly in how they are organized because of this situation. This type of freelancing would never and cannot be allowed on fire-based calls. The AFD follows a specific incident management system for fire calls, but when it comes to EMS, which happens to be a large majority of calls, no training or assistance is provided to the officer in charge (OIC).

The AFD decided to establish a standard organizational plan (OP) for all EMS calls. The philosophy behind the OP was to decentralize the decision-making process at the task level and treat all personnel on scene as paramedics. No longer do personnel on scene wait to be given an assignment by the lead medic or grab a gear bag or an assignment in an ad hoc manner. They know their role and area of responsibility before they arrive on scene. Each assignment is based on their apparatus seating position. Assigning roles according to seating assignments allows each person to know his area of responsibility before arriving on scene. This method eliminates duplication of tasks, reduces confusion on scene, simplifies communications, and reduces the time it takes to complete tasks.

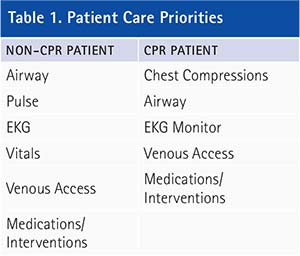

The OP is based on a set of priorities for two types of patients, CPR and non-CPR patients. Table 1 shows a list of priorities, in order, for both patients. Now, before the argument starts, it is understood the sequence of priorities is debatable. The OP addresses this issue by ensuring at a minimum that the first three priorities occur simultaneously. When a full crew arrives together, nearly all priorities are met simultaneously. By adequately addressing these priorities in this sequence, or simultaneously, superior patient care is provided. In addition, these priorities become the quality checks for the OIC.

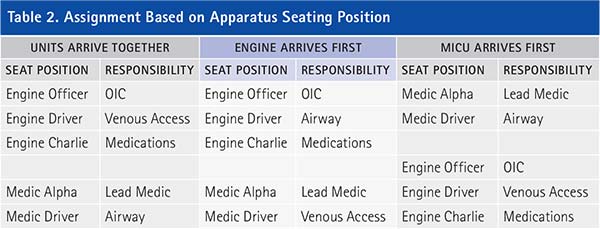

The OP had to be adapted for three possible scenarios. The AFD sends an MICU ambulance and an engine/truck with a minimum of three personnel to every EMS call; all personnel possess a paramedic certification. An OP was designed based on both units arriving simultaneously or within three minutes of each other. A second OP was designed based on the MICU arriving first and the engine/truck being more than three minutes out, leaving two paramedics handling patient care for an extended amount of time. A third OP was designed for the opposite situation, based on the engine/truck arriving first and the MICU being more than three minutes behind.

Table 2 shows a breakdown of each assignment based on the apparatus seating position according to the appropriate OP. The officer on the engine/truck always functions as the OIC. The engine Charlie seat’s (jump seat’s) responsibility is always medications. The Alpha seat of the MICU is always the lead medic. The only assignments that vary depending on the apparatus arrival sequence are the drivers. The first-arriving driver’s responsibility is always airway. If the apparatus arrive together, the MICU driver functions in the airway role. The second-arriving driver’s responsibility is always venous access. If they arrive together, the engine/truck driver functions in the venous access role.

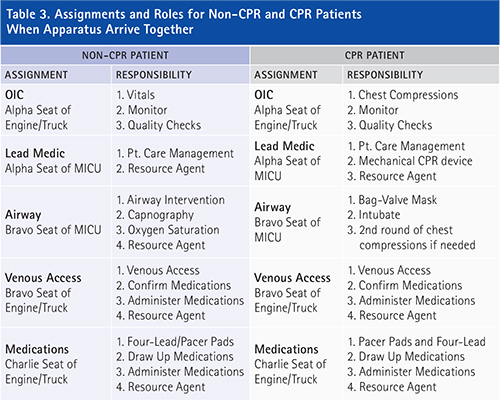

When all units arrive together or within three minutes of each other, the first four priorities for both patient types can be accomplished simultaneously. When the units’ arrival is staggered by more than three minutes, the first three priorities can be accomplished simultaneously. Table 3 shows a breakdown of assignments for non-CPR patients and CPR patients when both apparatus arrive together or within three minutes of each other. Each assignment has a sequence of responsibilities.

The OIC initiates manual chest compressions on all CPRs. The AFD carries a mechanical chest compression device on all MICUs, and personnel are to place the patient on the mechanical CPR device as soon as possible. The engine driver is assigned the venous access role and gains IV/intraosseous access if warranted by patient condition. In addition, the venous access position confirms all medications and can administer the medications. The medication role places the patient on the EKG on all medical calls. This might be limited to only the four-lead EKG but could include pacer pads on critical patients. The medication role draws up all medications, confirms medications with venous access position, and can administer medications. The venous access position and the medications position must work closely together and function as a team within a team. The airway position maintains the airway including intubating the patient. The lead medic directs patient care and can function as resource agent. A resource agent assists others when time allows.

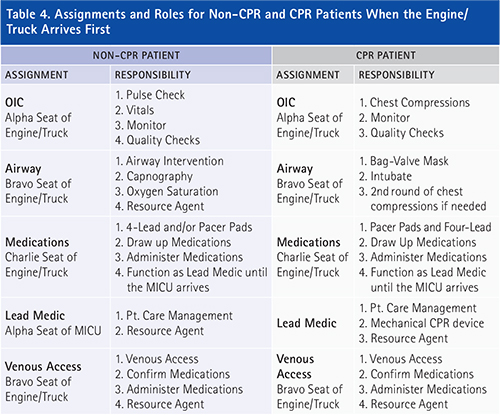

The roles vary to some degree when the apparatus do not arrive within three minutes of each other. Table 4 shows a breakdown of assignments for non-CPR patients and CPR patients when the engine/truck arrives at least three minutes before the MICU arrives. The engine/truck must provide quality patient care with only three personnel on scene. On non-CPR patients, the OIC initially does a quick pulse check and then starts initial vitals. The engine/truck driver responsibility is airway while the Charlie seat assignment has medications and must function as the lead medic until the MICU arrives. If the MICU has a significant delay, the medications individual will remain as the lead medic after the MICU arrives. This serves to maintain continuity of care and to avoid miscommunications. If this occurs, the Bravo seat of the MICU now has the responsibility of medications. Any personnel on the engine/truck can gain venous access prior to the MICU arriving on scene as long as it is in the proper order of priorities.

With CPR patients, the OIC begins chest compressions, the engine driver’s responsibility is airway, and the Charlie seat has medications. At this point, conducting ventilations with a bag-valve mask is an adequate airway; there is no need to focus on intubating the patient at this time. Charlie initially places the pacer pads and four-lead on the patient and then establishes venous access if the MICU is not on scene. Charlie will function as the lead medic until the MICU arrives. If the MICU has a significant delay, the medications individual will remain as the lead medic after the MICU arrives. The AFD does not carry a mechanical CPR device on the engines/trucks, so personnel may have to rotate performing chest compressions. If a rotation is required, the OIC and Bravo swap places.

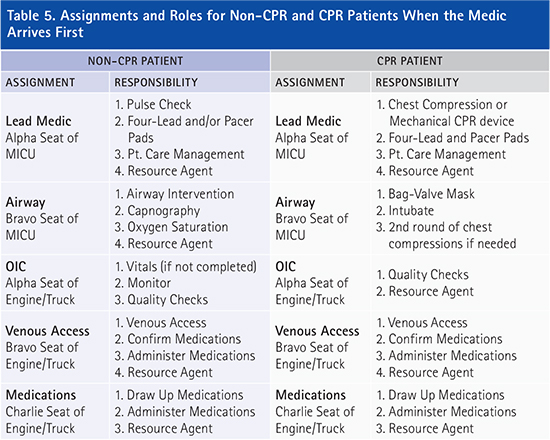

When the MICU arrives first on scene by more than three minutes, the roles will vary slightly once again. Table 5 shows a breakdown of assignments for non-CPR and CPR patients when the MICU arrives at least three minutes before the engine/truck arrives on scene. The MICU must provide quality patient care with only two personnel on scene. On non-CPR patients, the lead medic performs a quick pulse check and then places the patient on the four-lead and/or pacer pads. The lead medic is able to perform these two tasks while providing patient care management. The medic driver’s responsibility is airway. Once these priorities are met, either individual can gain venous access if the engine/truck is not on scene.

On CPR patients, the MICU will immediately place the patient on the mechanical CPR device or begin chest compressions. Once on the mechanical CPR device, the lead medic will place the patient on the pacer pads and four-lead. Once this is completed, the lead medic will obtain venous access. The medic driver’s responsibility is airway. At this point, conducting ventilations with a bag-valve mask is an adequate airway. If a mechanical CPR device is not available, the two paramedics will rotate between chest compressions and airway until the engine/truck arrives.

Once training started on the OP, it did not take long to see a significant improvement in scene organization, communications, and the time it took to complete tasks such as IVs or intubations. Within the first couple of sessions of training, scene communications became clearer. Personnel were not speaking over each other, and the patient was not asked the same questions multiple times by different paramedics. Speaking with OICs after the training, most felt they had a stronger control of the scene and what was occurring with the patients. The lead medics said they could now focus mainly on the patient and direct patient care since they did not have to direct or assign each task. One of the main intents of the OP was to decentralize the decision making at the task level. Speaking with the OICs and lead medics, the OP accomplished this goal.

The scene organization also improved after a couple of training sessions. Personnel know their roles and responsibilities and immediately went to their correct location. Simple tasks such as correct bag placement and removal of duplication increased the scene efficiency and organization. Each individual knew their responsibility when they arrived on scene. They knew which medical bag or piece of equipment to grab and where to position themselves according to the patient’s position. These simple actions significantly improved scene organization and efficiency.

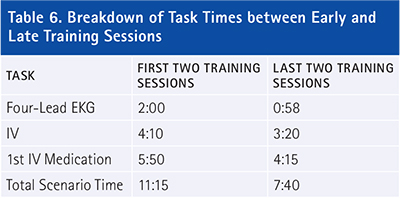

The biggest improvement seen from this training was the amount of time it took to complete tasks. Table 6 shows a breakdown of the first two training sessions and the last two training sessions relative to the time it took on average to place the patient on the four-lead EKG, start an IV, and administer the first medications as well as how long the average scenario lasted. The times are from patient contact.

It is clear AFD personnel were able to complete important tasks much sooner in the scenarios using the OP. There was significant improvement in all important tasks that impact patient care. Table 6 shows a few of the tasks that had the most improvement. The improvement in times is a result of all individuals knowing their area of responsibility when they arrived on scene. No paramedic is left waiting for an assignment before starting patient care. The paramedics know their assignment before they arrive on scene and start performing their function the second they make patient contact. The overall scenario times improved because the skills were occurring faster. This allowed the patient to be prepped and ready for transport sooner.

Plan Success

The AFD knew the OP worked in training, but did this success carry over into the field? The AFD performed an analysis on CPR patients, specifically looking at intubation times, first definitive therapy times, and scene times. Definitive therapy was defined as any lifesaving task such as defibrillation or medication administration. The CPR patients were divided into two groups-CPR patients before and after the OP training. The results showed a 45-percent reduction in the time it took to intubate a patient after the OP training. This was similar to the results seen in the training. The time to first definitive therapy was reduced by 47 percent after OP training, and scene times went down by 25 percent. These results were similar to what was witnessed in training. The sample size for this analysis is too small to validate the data, but the trends are very promising.

When crews that used the OP on any type of medical call were surveyed, statements like, “That was the smoothest CPR I have ever been on,” “There was no chaos on that call,” and “Everybody knew their role and we just went to work,” were expressed. From the statements from crews that use the OP, the training sessions, and the analytical data, it is clear the OP to organize EMS works.

The AFD provides a plan for crews before they arrive on scene. This organizes and streamlines the scene and decentralizes the decision-making process at the task level. There is no doubt the AFD’s OP is a complete success.

CASEY McCASLIN, a 14-year veteran of the fire service, is battalion chief with the Allen (TX) Fire Department. He has a master’s degree in public affairs and a B.S. degree in biology. He is an Executive Fire Officer alumnus; a licensed paramedic; and a rope rescue, confined space, and trench technician. He previously was an EMT and a paramedic instructor at Collin College.