FDNY Firefighter Ray Pfeifer, 59, passed away on May 28, 2017, after a long battle with cancer. Pfeifer, who himself spent months digging through the debris at Ground Zero after the 9/11 terror attack on the World Trade Center, was a leading advocate for health care for Sept. 11 first responders.

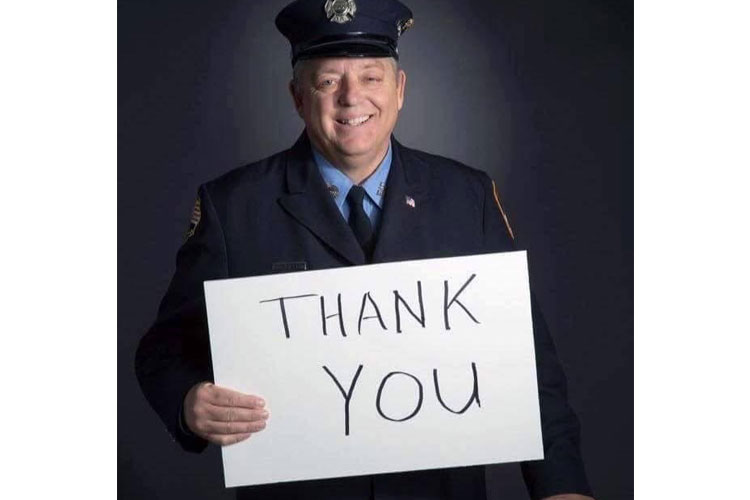

Below is Ray’s eulogy, composed by FDNY Captain Sean Newman, a longtime friend and co-worker. Thanks to Billy Owens and Mike Dugan for providing the text. Photo above courtesy of Billy Goldfeder.

A Final Irish Goodbye

Sometimes, television shows or movies that you watched during a particular period of your life, especially in times of crisis or grief, become associated with those real-life events later on. In the early 2000s, two series come to mind: Band of Brothers (taken from a quote from Shakespeare’s Henry V ) and The Lord of the Rings , which are now forever linked, for me at least, with 9/11. At the conclusion of The Rings film trilogy in 2003, Frodo and his Uncle Bilbo sailed away to the Undying Lands in the West on an Elf ship under the protection of Elfish magic. The burden of wearing the ring was extraordinarily high, and only Hobbits possessed the inner strength to not be completely seduced by the ring’s evil magic. After their journey and mission had reached its end, Frodo and Bilbo were no longer whole. They were psychically, mentally and spiritually shattered but the Elves could at least provide them with some level of comfort and solace in their remaining years.

The author of the series, J.R.R. Tolkien, a British WWI veteran, who participated at the Battle of Somme in July 1916, wrote of his trilogy’s main protagonist:

“Frodo undertook his quest out of love – to save the world he knew from disaster at his own expense, if he could; and also in complete humility, acknowledging that he was wholly inadequate to the task. His real contract was only to do what he could, to try to find a way, and to go as far on the road as his strength of mind and body allowed. He did that.”

Does that description remind you of anybody?

In the Aftermath

Raymond Pfeifer, who died on May 28 after an eight-year battle with cancer that is certainly linked to his exposures at the WTC, had real journeys and battles that were far more heroic that Frodo’s–an obvious statement but one that deserves examination.

On the morning of September 11th while at a fire department golf tournament in Ocean City, Maryland, Ray jumped in a car with other members of 40/35 and raced back to the firehouse as soon as they heard the news of the attacks. They got back so quickly that Ray and the crew made it down to the WTC faster than some members who had come from home. Ray was exposed to the toxic smoke, ash and debris from the fallen towers very early. Ray was even present when 7 World Trade Center, a 47-story building on the north side of Vesey Street, came down in the late afternoon after burning from top-to-bottom for hours, injecting another volley of poisonous dust and debris on an area already blanketed in harmful silt. Ray, as the de facto sergeant major of The Cavemen, along with our officers, lead us as we dug until dawn the next day, and then in loosely-formed groups on successive days that turned into weeks, and finally months.

With Bruce Gary from the engine and Jimmy Giberson from the truck lost, 40/35 lost its (somewhat imposing) firehouse leaders. Twelve men total were lost from the house that day (the 12th was a detailed firefighter from Engine 23, who had come for just the day tour). Our losses were inconceivable. The number of firefighters lost in our firehouse alone matched the number killed in FDNY’s worst day to that point: the 23rd Street Fire on October 17, 1966. FDNY’s total number of line-of-duty fatalities, a figure that has been tracked since the Department formed in 1865, surged 50 percent in one half hour period–the time between collapses. Our losses were absolute. Even our Chief of Department was killed, and everyone from all levels of the Department, from headquarters to the firehouse, were overwhelmed. We were not getting the usual support anytime soon; the scope of the tragedy was too great and everyone was spread too thin. Someone had to take charge. Ray instantly filled the leadership void at the firehouse, supporting the families of our lost members, attending the services and memorials for men lost at our firehouse, and rallying us to go to memorials and funerals of any lost FDNY member (On one day in October, there were over 20 services Department-wide). And Ray wasn’t any one family’s firehouse liaison (a time honored role when an active member dies), he was every family’s liaison, always advising the member assigned to the respective family. This was a done around, and during, his regular firehouse tours.

At the same time we were trying to rebuild our rosters, and our fire engine and truck, we were also trying to renew our souls (though we did not admit it then). The most important task in the fall of 2001 was digging on the “pile,” which slowly became the “pit” (Ray, like most firemen, detested the media term “Ground Zero”) as autumn turned to winter during our ceaseless search for the remains for not just our lost brethren, but for all the victims, who deserved to depart the World Trade Center under an honor-guard escort, and not in the back of a dump truck amongst building wreckage. Ray’s was one of many strong voices demanding their dignified departure.

In his spare time, Ray accepted six-foot checks with lots of zeros on behalf of the Department and the UFA from donors across the country, presented in some of the fanciest hotels and venues in the City. We were frequently recruited to join him on these escapades, and sometimes he even dragged us out afterwards for “just one.”

What makes Ray’s contributions during an impossible time, testing the limits of endurance, comprehension and sanity, was that when it was over, there was no Elfish magic to protect him for the remainder of his life. If there had been such an enchantment, he would still be here. Ray was ever present in the pit until the bitter end, when the last column was removed from the site on May 30th, 2002, concluding a painfully incomplete recovery period as barely half the remains of FDNY members were found (Ray would donate his Key to NYC for his work on the Zadroga Act extension to the WTC museum on that anniversary in 2016). The particles lodged in his body caused illness in a very short time. Ray could not sail away on “Between Tours II” heading west into the sunset as Frodo had done; it would not have been him anyway, because he had more work ahead of him–special work. Work that only he could accomplish as the face, cane, and, finally, wheelchair of the opposition to congress’s plan to let 9/11 responder health protections lapse. That is not to say that Ray would not have spun a yarn and convinced you that he indeed had sailed on an Elfish ship. Before Ray’s last few years are addressed, it important to paint a picture of Ray–the real Ray–Ray in his prime.

Bending the Truth

This may not come as shock if you knew Ray well, but he could tell the occasional white lie. Everybody knew it, and it did not matter; it was woven into his charisma. But there was always something gentle and protective about his little fibs. Yes they were meant to deceive, but never to betray.

Here are some examples of Ray stretching the truth:

“I’m on my way.”

“I’m not leaving yet.”

“The chief said it was okay.”

“Yes, I know him.” (Ray could never admit that you knew someone that he didn’t, especially a fellow firefighter)

“You won’t get into trouble for that.”

After 9-11, Ray was quick to say that the FDNY was still the greatest job in the world, which seemed delusional then, but that was exactly what Ray thought we needed. Not unlike Paul Newman’s character in Slapshot , Reggie Dunlop, the player-coach for the minor league Charlestown Chiefs hockey team, who fabricated one lie after another, along with crazy schemes to build arena attendance, to save a franchise that was folding after years of losing seasons, compounded by the closing of the town mill. Just as Ray could not reverse the attacks on the WTC, Reggie couldn’t save the team, but their respective actions ensured that tragedy did not also break everyone’s spirit. Sometimes foolish hope is better than no hope at all.

Ray was also famous for his Irish goodbye, which was uncanny for someone of his size and presence. He always led from the front, but sometimes he left from the rear. His ability to sneak out when no one was looking was another gentle lie in a sense. By not saying goodbye, he was really telling everyone that he was still there–a very Ray thing to do. It is not that he couldn’t say goodbye, I believe, he just hated saying no, to anyone, about anything. To Ray, goodbye was the same as no (I can no longer be with you), and that was best left unspoken. For most us outside his closest family and friends, that is exactly how Ray said his last goodbye.

Ray, The Babe, and the Boston Blessing

His white lies were part of a greater truth, even a modern mythology, where themes, lessons and priorities are passed down through story—hovering between fact and fiction. Ray knew that to build pride in the current members of the house, and make them proper stewards of its future, they needed to feel connected to their past, bound to its legends. Ray, who became a fireman in the 1980s, even intersected with some Korean War veterans who were winding down their careers in the firehouse, oldtimers like the infamous “Murderers’ Row,” borrowed from the 1927 New York Yankees (Ray was a Yankees fan from Long Island – they do exist) and other legendary figures who performed now unattainable exploits, either on the fireground or against some hapless officer in the firehouse.

We knew we could never be worthy of our firehouse antecedents, we could never be tough enough, daring enough, but, maybe, just maybe, future generations would feel the same about us (you see, a little self-deception is useful). Ray knew that myth reinforces a code of conduct. Will the 9/11 legacy make for FDNY legends? I’m not sure about us, but Ray’s acts, and those that sacrificed everything at the WTC, have already coalesced into a legend that will resonant for generations.

Speaking of legends (and the Yankees), Ray was our Babe Ruth. They were both the same height (6’2”), the same size (larger than life), and they played by the same rule book (their own). And, sadly, both Ray and Babe Ruth died of cancer in their 50s. It is fitting that Ray had the deepest of connections with members of the Boston Fire Department (BFD), who, despite being New York’s archrival in baseball, made intractable when Ruth was traded from the Red Sox to the Yankees in 1919, were some of his closest friends over three decades. The relationship with BFD started in the late 1980s when Ray stayed in the quarters of Engine 37/Ladder 26 while his wife, Caryn, was underwent a serious surgery and lengthy recovery in a Boston hospital. The relationship expanded to include 14/4 on Dudley Street, and grew with annual trips to each city’s Saint Patrick’s Day Parades, and Yankees-Red Sox baseball series. After 9/11, Boston firemen rode Amtrak to NYC more than some train conductors in their ceaseless journeys to lend support and attend services.

On May 24th, 2002, Ray was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at Fenway Park in honor of John Ginley, Ray’s lieutenant who was killed on 9/11 (a rare New Yorker Red Sox fan). “I was the only guy ever who wore a Yankees hat in Fenway Park but didn’t get booed,” Ray said during a Washington Post interview in 2002. Ray added later that just before he was about the throw out the first pitch, he quickly put on the Yankees cap that he had hidden somewhere under his clothes, becoming the only person to ever do so in Fenway (so Ray says). It is also fitting that one of the final toasts to Ray included a special-edition bottle of scotch, his favorite liquor, which had a label adorned with Yankee pinstripes.

Unlike The Babe, Ray did not hit 714 lifetime home runs and he did not have a career .342 batting average, but some statistics unrelated to sports can mean so much more. The Zadroga act extension covers the WTC health program for 75 years at a cost of $3.5 billion for 73,000 recovery workers, and those recipients are indebted to Ray, and (in his words) his “guerilla lobbying” for a bill extension that would surely have died on the senate floor in 2015. Because of Ray, 5,400 people that have been diagnosed with cancers linked to the 9/11 attacks are now covered, and that number is growing rapidly.

Fireman Ray Pfeifer

He was quick to remind anyone that he was hired as a “fireman” (on February 17, 1987)–the “firefighter” title would come shortly after (I’m actually not 100 percent sure about that). Ray’s dedication to Engine Co. 40 was absolute. His transfer record has but one entry: “ to ENG040” when he graduated probationary firemen school on April 9, 1987. Ray found his home. He was now a FDNY engineman, and the truck members were forever “fireman’s helpers,” as they do not actually extinguish the fire–that sacred work is only for engine members that reach hydrants, stretch hose, count lengths, and ultimately open a nozzle on the fire, but not before getting as close as humanly possible to the fire’s origin. That was Ray’s job. Though it was no Ray original (he would take credit for it, though), he would remind us that truckies go to Medal Day, and enginemen go to the Burn Center. He took equal pride in all the engine positions: backup, the nozzle, the door, control, and, of course, chauffeur, the position that Ray is probably best known. When he worked “across the floor” in Ladder 35, the canman position became “the nozzle.” Only Ray could elevate what is usually the most junior position in the ladder company to the highest level of importance and gravitas.

From what Ray would call “outerborough” firemen from “three-digit companies,” there is a prevailing joke that that Manhattan firefighters name all their fires. Even though many fires in brownstones, tenements, subways and stores, even high-rise buildings, have been extinguished without fanfare or a naming ceremony, there is indeed some truth to the claim, which makes Ray the ultimate Manhattan fireman. Here are a few examples of difficult, even deadly, fires that Ray had participated in his years of service in E-40:

MTV (late 1980s) – the fire was so dangerous that laws were changed because of it, allowing firefighters who are injured at fires to sue building owners for negligence. Lionel Hampton (January 1997) – A halogen lamp ignited a wind-driven fire that was so intense that two 2-½ inch hoselines operating side-by-side down the long public hallway could not make headway for half an hour, requiring scores of enginemen to rotate in and out. Ray, and dozens of his brethren, tried valiantly put out this fire under impossible conditions.

Macaulay Culkin (December 1998) – the fire was so hot it burned through the hoseline that was bowed about three feet in the air in the public hallway. Ray, as the controlman, was cut off from the nozzle team due to the intense heat, and was witnessed by a member of Engine 54/Ladder 4, who was just reaching the fire floor, escaping to the stairwell landing while giving a Mayday over the handie-talkie for his trapped colleagues as he was laying on his back and literally steaming from the heat. Most firefighters bailing out of an untenable fire area would only be concerned for their own survival, at least until they could briefly recover, but Ray’s foremost concern, even as his body burned, was the safety of his colleagues.

Father’s Day (June 2001) – Ray arrived just minutes after the explosion-collapse in a hardware store in Astoria while driving the laundry van on a light-duty assignment (during a period of convalescence). He eventually met up with members of Ladder 35, who were sent as an additional truck. Those working that day thought it would be the worst one of their careers, a day when three FDNY members perished, which happened just three months before 9/11.

Ray Joins the ‘Death Star’

About a year after 9/11, Ray surprised everyone by taking a detail to headquarters to be the aide to Chief Joseph Pfeifer, who had recently been promoted to Deputy Assistant Chief, and was put in charge of the newly-formed Planning and Strategy unit. Ray and Joe were not related (rules prohibited family relations from working closely together), but both Ray and the chief insisted that they were not related (everyone believed Joe). Despite being complete opposites in personality and their respective brands of genius, thus began Ray’s seven-year run as Chief Pfeifer’s driver and back-room dealmaker. For his entire career, Ray was a self-proclaimed union man. He was the company and battalion delegate, and this move to headquarters was inexplicable, but his new aide position brought him in direct contact with the Department’s highest leadership, many of the same men that Ray found himself on opposite sides of the table as a delegate. In a short time, Ray made friends, and maybe a few…well, not exactly enemies…but those who didn’t exactly embrace the Ray act. Needless to say, everyone on the seventh floor knew Ray. By the way, I can tell you this now: if the fountain on his desk was unplugged and not gurgling water, it meant he was not around (“10-8 Code 2’). Fittingly, when the 2003 East Coast blackout hit, water was not flowing in the fountain, and not because of the power outage, as he was already floating in his backyard pool with a drink in his hand (as he bragged on his cell phone that evening), thus avoiding to have to work the next 24 hours at headquarters in support of the FDNY operations center. He did offer to come in, but he did not exactly resist when the chief told him to stay home.

The Planning Unit branched off to become the Center for Terrorism and Disaster Preparedness in 2004 at Fort Totten in Bayside, Queens. Ray now had two bases of operation to work his ever expanding network. And, just as important, Ray now had waterfront property. His beatification projects over the years (some authorized, some not) included aggressive hedging of water-side flora to improve the view (he would claim a collapse hazard) and an expanded parking lot that appeared literally overnight. When he didn’t have to pick up the chief in Middle Village, Ray prided himself on getting to the Fort early (I think he was up at 3:30 every day morning), and I’ll forever remember the many sunrise photos overlooking Little Neck Bay that he took from the front porch that he broadcasted out on social media. His only unfinished work was a dock for “Between Tours.” If he had remained on active duty for bit longer, I am sure a Coast Guard vessel would have been evicted for a personal FD boat. At the very least, he would have secured a slip.

The FDNY’s Incomparable Meta-Leader

Fort Totten may have been idyllic, but Ray was never idle. Still spending half his week at headquarters with the chief, Ray grabbed onto several projects where others had failed, and memorialized in a school paper, written in 2008, on a concept called meta-leadership. Here is an excerpt:

Meta-leaders transcend rank and position to get the job done. These leaders work in the gray areas of an organization and do their best work with the least number of rules and oversight. Instead of being discouraged by ambiguity and confusion, they thrive in it. The FDNY’s ultimate meta-leader, Fireman Raymond Pfeifer, a 21-year veteran, has been Deputy Assistant Chief Joseph W. Pfeifer’s aide (no relation) for the past five years. As the chief’s driver and assistant, Ray has access to powerful people at FDNY headquarters who sit far down the organizational chart, and more importantly, he has built relationships with influential people outside the department. When everyone else fails, call Ray.

One project, which suffered repeated failures, could not have been completed without Ray’s unconventional style of leadership. The FDNY Bureau of Communications had made several attempts to send video footage from incidents back to headquarters with a communications vehicle, but no contractor made that type of truck for first responders and the project was abandoned. With no real authority, no experience in communications, and no technical knowledge, Ray decided that a truck needed to be built from scratch. After a few months of negotiations and modifications, a converted ambulance was streaming video to headquarters to the amazement of staff chiefs and participants in the private sector.

WHY IS RAY EFFECTIVE?

For this discussion, the technical issues of the project are not as important as the reasons why Ray is so effective. Even though he has never heard the term, Ray intuitively practices the most important traits of meta-leadership.

Meta-Leader Statement No. 1: “the meta-leader must often give life to a vision or objective that does not already exist. Exceptional talent is required to describe that bigger picture and then imbue it with meaning.”[i]

When Ray approached Verizon about getting the equipment and access needed to transmit during incidents, he knew that he did not have much leverage. The FDNY could not pay the phone company much, and to make matters worse, research and development is not a high priority in DHS grant funding. Instead, he sought “buy in” by showing the documentary 9-11 by Gideon and Jules Naudet, the French brothers who filmed both WTC collapses. Ray’s contacts at Verizon were moved by the quiet professionalism of the firefighters in the lobby of Tower 1, many whom did not return. By showing the documentary, Ray was able to show the importance of situational awareness and communications far better than a routine PowerPoint presentation, fostering a sense of civic duty in the Verizon staff.

Similar to George Washington, Ray invites people to participate in his vision.[ii] Key players can help build alliances, as seen with the appointment of the Marquis de Lafayette from France during the Revolutionary War.[iii] The point here is that “people support what they help create.”[iv] Or in Ray Pfeifer’s words: “make them think it is their idea.”

Meta-Leader Statement No. 2: Experts in a domain are prone to “entrained thinking,” and they may overlook or dismiss the innovative suggestions of non-experts. Experts have invested in their knowledge base, and they are unlikely to tolerate controversial ideas.[v]

Many full-time members of the FDNY Communications’ office told Ray that his vision of a roving communications’ vehicle was impossible. They told him that New York City’s many high-rise buildings would make satellite transmissions unreliable. According to Ray Pfeifer, “I like to prove everyone wrong.”[vi] Instead of arguing the technical problems of satellite-based communications’ vehicles, which are used primarily by the military, Ray found a way to circumvent it. He had the truck configured to use Verizon’s hundreds of cell phone sites for data transmissions, and the truck was also equipped with a device that could turn the vehicle into its own cell-phone transmission tower, if necessary. There was no precedent for such a vehicle in the first responder community. According to Pfeifer, “nothing came off the shelf.”[vii] Because Ray was the so-called non-expert with an innovative idea, he did not know enough about the technologies to be discouraged. Ray proved that innovations sometimes come from the fringe.

Meta-Leader Statement No. 3: “ Meta-leaders are able to accomplish the task, feeling and acting at ease even when engaging with people outside their professional domain or expertise, able to act comfortably in someone else’s space and making others feel welcomed and accepted.”[viii]

About three years ago, Ray was driving through the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the chief’s command car near his old firehouse when he heard a fire announced over the department radio. He decided to take a quick detour to see if his old buddies were safe. By the time he arrived, the fire had been extinguished and many of the firemen were in the street tending to their tools and packing hose. A number of firemen flocked over to see Ray but they were not alone. After 20 years of fighting fires in the area, Ray has many civilian friends who also came over to catch up. With a congregation of firemen, shop owners and dog walkers, quite a crowd had formed on Ray’s corner. He caused such commotion, that actor Tony Danza, who was filming The Tony Danza Show at the time, walked through the crowd unnoticed and a bit disappointed by his sudden anonymity.[ix] The meeting was not part of an interagency event, but it shows how a meta-leader can be an “attractor” that resonates with people.[x]

When I showed this essay to Ray nine years ago, it was one the rare times he became quiet and a little embarrassed. He was taken back by being the subject of an class paper, but he he deserved the treatment. In another, similar, story, FDNY was having trouble getting the local news helicopters to sign a deal where they would provide the Department with video feeds at fires and other emergencies in exchange for better access to restricted air space. Ray stepped in and had a meeting with one his contacts, and the first local news station came onboard. Soon, all but one had agreed, and now FDNY has another means to improve its situational awareness at incidents. After his cancer diagnosis in 2009, and subsequent surgeries, Ray slowly phased out as Chief Pfeifer’s aide, but remained at CTDP for a time, holding court in the kitchen, slowed in body but not mind.

The Pfeifer Act

The bill, which became an act in 2010, which Ray worked so hard to have extended was named after James Zadroga, a NYPD detective that died of a WTC-related illness in 2006. All responders are forever grateful for the sacrifice that Det. Zadroga made. The act only provided us coverage for five years, and with the deadline approaching fast in 2015, Ray, and many other responders and advocates (some had started this lobbying much earlier that Ray), swarmed Washington D.C. until the extension was passed. A FDNY EMT, who knew Ray very well, said outside his wake service that the act “may be called Zadroga, but it was Ray’s fight.” Posterity may one day decide to rename the extension the Zadroga-Pfeifer Act to give balance to not just what it took to get it passed, but what it took to get it extended. And as we all know, Ray always had an act anyway.

Looking back, I am amazed at how consistent Ray’s personality was. He was same person in the firehouse kitchen, at the union hall, at a fire, in the pit downtown, at headquarters, or later, in the hallways and office of our elected officials in D.C. He was a fractal–those geometric shapes that give you the same picture no matter how wide or narrow the focus. It did not matter if he was talking to senators, governors, CEOs, mayors, or high-ranking department members: you always got the same Ray, and he probably called you by your first name.

The Last Suppers

In one of the most impressive displays of fortitude of have ever witnessed, Ray kept his sense of humor right up to the end. He started the “Last Supper” series about five years ago, held at Miller’s Ale House in Levittown, the town where, as he was quick to remind you, he had grown up. He hosted at least 20 Last Suppers, usually mid-afternoon lunches, and any variety of Friends of Ray would show. From the west, Miller’s it came up fast on Hempstead Turnpike–it was easy to pass by–but you couldn’t miss his fire engine parked in front.

Also, to the dismay of high-ranking chiefs and other leaders, Ray placed countless “deathbed requests” to give his friends a gentle nudge on transfers or other favors. I didn’t ask, but Ray put in such a request for me in 2009 when had just fallen ill. I didn’t get my first choice; the chiefs were on to Ray early.

At the funeral, the Bishop of the Diocese of Rockville Centre (covering all of Long Island) called described our fallen brother as a “Ray of Light. ” At the collation, Ray’s East Meadow Fire Department buddies made up shirts that said “Ray of Hope.” Former FDNY Fire Commissioner and Chief of Department Sal Cassano called Ray our ambassador. They were all right.

Farewell

Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Supreme Court justice, said that many people die with their music still in them. It was clear that Ray was not one of those people. His accomplishments, and his enjoyment of family and friends will resonate for quite a long time. Ray, who never shied away from a fight, was thrown into not one, but two wars that never end: firefighting and terrorism, which intersected with his life so violently in 2001.

Ray, you led us as firemen, you led us as men, you led us in joy, you led us in sorrow, you led us in wonder, you led us in spirit, you led us in pride, you led us in defiance, you led us in renewal, you led us in life, you led us in illness, and, finally, you led us in death.

To honor his legacy, embrace the people and causes that matter most to you, but do not try to be too much like Ray, you’ll get into more trouble than he did.

“Of comfort no man speak:

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs;

Make dust our paper, and with rainy eyes

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth.

Let’s choose executors, and talk of wills.

For God’s sake, let us sit upon the ground,

And tell sad stories of the death of kings.”

William Shakespeare, Richard II

We have surely lost an irreplaceable king, and it is our responsibility to continue his mission and tell his stories, which time will turn to legend.