By Craig Nelson and Dane Carley

Often, because of tradition, new firefighters begin their career in a fire academy or some other type of organized training by practicing the same skills over and over and over. We pull hose, bed hose, pull hose, bed hose, pull hose, bed it, and then pull it again. We throw a ladder, take it down, throw it again, take it down, and throw it again. We practice each critical firefighting skill until it becomes second nature. The combination of being young and feeling confident in our skills leads many to exude this confidence toward the end of the training–some may even become cocky. After graduation, the new firefighters move to a fire station and begin responding on calls. In their mind, life is going to be easy because all of the training is done. Right? It is likely, however, that the firefighter finds a company officer who continues drilling the skills (hopefully). It is also likely that senior firefighters knock them back a couple of notches. It seems like some of our senior personnel enjoy reminding “the kids” that they are lower than pond scum. Although members’ intent in knocking down “the kid” a few notches may be good, this may fit the definition of hazing. Some of this process is great; in fact, processes with similar intents should be used all the way up the promotional ladder. Learning, this month’s Reliability Oriented Employee Behavior (Ericksen & Dyer, 2004), is about learning a skill so well that it becomes second nature. Thus, we do not fail under pressure, not only as firefighters but also as a fire department.

This example illustrates how individuals learn to excel; but, can a fire department learn in a similar way? A successful business becomes successful through ongoing learning. Can a fire department do the same? The concept is more complicated with a fire department or business, but it is still possible. Can you think of positive examples in the media of departments implementing new programs to improve services? These are examples of learning departments improving operations based on what they learned. Employees in a successful business practice processes proven to work until they become second nature. The business or fire department looks at less successful processes and learns where there are weaknesses or opportunities in their services, products, or organization. It is an ongoing cycle of implementing improvements and starting the learning cycle over again in an effort to always be at its best. This is similar to many aspects already practiced in the fire service such as near-miss reporting, tailboard talks, critiques, and after-action reviews.

You may be asking, “Why are we being compared to a business?” One reason to compare the fire service to a business is because businesses provide goods or services to customers much as a fire department. Do you consider your fire station a place of business? Or is your fire station a home-away-from-home where things carry on today much as they did 50 years ago? How many successful businesses are still doing things the same today as they did them 50 years ago and are still around? Today’s competitive, free-market environment makes the second choice a slow road to failure. As individuals, we may face the challenge of making it down a hot hallway to an open door leading to a fire room, but we still face it even though it may not be easy or convenient. A fire department that does not learn to become better is the same as staying outside and watching the apartment burn to the ground. Maintaining the status quo is failing when compared to other departments in the industry that are moving forward. (Oakley & Krug, 1994) A successful business provides a valuable service or product to its customers by constantly learning what works and what does not; what the customer considers valuable; and which processes are most effective. The fire service can use similar processes to enhance what is already in place and expand the learning behavior beyond the fireground.

Combining our tradition of training until skills become second nature, tweaking our tradition of hazing into something more effective, and looking at our service as a business can all help us improve our value to the community while improving our safety–all occur through constant learning.

Learning

Successful businesses use systems to repeat success. One system used in a variety of high-risk industries is higher reliability organizing (HRO), which is the topic of the Tailboard Talk column. The cornerstone of an HRO is ongoing learning. A constant drive to learn as a firefighter, company, shift, and department is a fundamental behavior for safety, success, and higher reliability.

The fire service has a history of testing for and hiring the most qualified individuals. However, learning about the profession should not stop until the day of retirement; and for those who are successful in the fire service, it does not.

The learning we have been discussing has two approaches–internal and external. Internal and external learning are similar to attacking a fire from the exterior or interior. The two methods are separate, but both are important to a successful operation in different situations. We focus our learning internally to improve our skills as individuals and crews, and externally to improve our operations as a successful fire department.

Learning Systems Used by Successful Fire Departments

Commonly Used

RIT teams

Accountability

ICS/NIMS

After Action Reviews / tailboard talks / critiques

Fireground live training evolutions

Firefighter I/II Certification programs

Paramedic quality control

NFIRS

Emerging Systems Successful Departments Will Consider in the Future

Emerging Systems

HRO (High Reliability Organizing)

CRM (Crew Resource Management)

National Firefighter Near-Miss Reporting System

Internal Learning

One of the most common internal behaviors seen in the fire service is overtraining on critical tasks. We put on so many self-contained breathing apparatus, pull so much hose, and throw so many ladders that we can do those tasks without much thought. This enables us to perform critical tasks and process other information at the same time because we have overtrained on them. We have learned them so well that we can perform at a higher level by accomplishing more.

Another behavior is our internal ability to knock down someone who is overconfident. Although the intent is right, the method usually involves some form of hazing. Not only is hazing unacceptable in a professional sense, but it also reduces long-term trust and negatively affects communication. However, overconfidence is a dangerous behavior that affects one’s ability to learn, so finding an effective way of keeping overconfidence in check is important as well.

After-action reviews and tailboard talks are increasingly common. It is critical to the process that we learn from them, whether successes or failures. Tailboard talks help a crew learn, and formal after action reviews help the department learn. In the case of near-miss reporting, the entire fire service can learn by reporting incidents at the Firefighter Near Miss Reporting System.

External Learning

We are guessing that at some point in every reader’s career you have brought an idea forward and heard, “That won’t work here” or “Why would we want to do that?” Unfortunately, resistance to change is normal no matter where you are–contrary to popular belief, the fire service does not have the corner on the market. Also contrary to the popular saying, “125 years of tradition unimpeded by progress,” the fire service does adopt many successful changes. The difference between successful fire departments and less successful fire departments, though, lies in the capability of an organization’s leadership to overcome the resistance and bring positive change to the organization. This often happens in successful organizations where members are involved with the change by learning why the changes are important to their success and have a say in how the change is implemented.

Being aware of and learning about a fire department’s surroundings also promotes the learning behavior and increases the success of the fire department. Some easy ways for fire departments to encourage their personnel to learn is by formally encouraging members to look at fire industry Web sites (like Fire Engineering), articles, and books. Personnel can also learn when encouraged to attend training conferences and schools. Articles on emerging trends in other industries are even important because some outside operational ideas and technologies may transfer well into the fire service. Talking about these ideas over the kitchen table or at a meeting could turn into to the next successful idea for your fire department.

Everyone likes to call themselves progressive as long as they don’t need to change.

Being aware of the department’s surroundings also means learning about local city, county, and state politics. How is a new initiative at the state level going to affect the city council’s decision making on staffing? Will it affect money available for training? How can we offset some of the impact?

Last, no single fire department can have enough incidents on every kind of call to build data from which to learn. So, it is helpful to look outside your department at how other departments have succeeded or failed and what was learned from the experience. What operations are most effective? What programs work well?

Case Study

The following case study is from www.firefighternearmiss.com. The near miss report, 05-0000218, is not edited–with the exception of highlighting the relevant points in this particular case because it is longer. We were not involved in this incident and do not know the department involved so we make certain assumptions based on our fire service experience to relate the incident to the discussion above.

|

Event Description At approximately 05:00 hours, May 10, 2005, we were dispatched to a restaurant on fire. The weather was cool and clear. All personnel were entering the final hour of their 24 hour shift. All of the responding companies work in an extremely busy part of town in a large city in (state name deleted). The responding companies consisted of 2 District Chiefs, 4 Engine Companies, 2 Ladder Companies, 1 Basic Life Support Ambulance, 1 Paramedic Squad Unit and 1 Safety Officer. The first arriving Engine Co. arrived on scene reporting fire showing from the roof of a one-story restaurant in a strip shopping center. The Engine Co. stated they were making a fast attack on the fire. The District Chief arrived on scene at the same time and assumed command of the fire. Two other Engine Co.’s and two Ladder Co.’s arrived on location less than one minute later. The Incident Commander assigned a Rapid Intervention Team and instructed another Engine Co. to lay a supply line to the attack engine. The IC then ordered the second Engine Co. to assist the first arriving Engine Co. with attacking the fire. The IC instructed the first Ladder Co. to begin forcible entry operations and check for possible extension in the adjoining businesses. I was assigned to the second arriving Ladder Co. As we arrived on scene, I could see the fire burning along the roof line on the front of the building. A large sign with the name of the business was also on fire. There appeared to be some burning debris on the ground beneath the sign and near the building. My first impression of the fire was nothing more than an electrical short which caused the sign to catch fire and some of the debris had fallen to the ground. I reported to the IC that my Company was on location and ready for assignment. The IC ordered my crew to assist with forcible entry and to begin Primary Search. I acknowledged the orders and we proceeded to maneuver the Ladder Truck into position at the front of the building. As we approached the front of the building, I continued to assess the situation. Suddenly, the large sign fell from the facade landing on top of two firefighters. The sign was approximately 20′(L) x 5′ (H) x 1′ (W)).I reported the collapse to the IC along with the fact that a firefighter was trapped beneath the sign. I then informed my crew that there was a collapse and firefighters were trapped. At this time, the Engineer/Operator assigned to the first arriving Engine Co. called for a May-Day. My crew and I ran to the aid of the downed firefighters. Several crews converged on the collapse zone at the same time. I could only see one firefighter at this time, and he was trapped under the middle portion of the sign. I took a position at the head of the injured firefighter. (NOTE: This firefighter was the Acting Captain during this shift.) I could clearly see his face through his face piece. He appeared to be unconscious and did not respond when I asked if he could hear me. At this moment, there were probably a dozen or more firefighters at the site of the collapse, most of whom were assisting in lifting the sign enough to allow the others to pull the firefighter free from his entrapment. Once we pulled him clear of the collapse zone, I again tried to determine his level of consciousness while the others began assessing his injuries. It was difficult to tell if he was breathing at first, due to all of his Turnout Gear. Again, he did not respond to my voice. About 30 seconds after we removed him from the collapse zone, the firefighter opened his eyes and slowly began answering questions appropriately. The second firefighter involved in the collapse was trapped, momentarily, from the waist down. (NOTE: This firefighter was a Temporary Fill-In Firefighter normally assigned to another station in another district.) He was able to extricate himself and immediately went to the aid of the other firefighter. He attempted to lift the large sign off of the firefighter but was unable to move it. Not realizing how badly he was injured and working off of adrenalin, he retrieved an attack line and started to spray water on the burning building to protect the other firefighters from further collapse. Once both firefighters were out of harm’s way, they were immobilized using spine boards and transported to an area trauma center for further assessment of their injuries. Both were treated and released from the hospital later that same morning. One remains off-duty due to his injuries one week after the incident.

In summary:

The first arriving Engine Co. consisted of the following personnel: (1) Acting Captain – This individual was promoted to Engineer/Operator (E/O) less than one year ago. He transferred to this station approximately two weeks prior to this fire and is assigned as an E/O on one of the ambulances assigned to the station. This is the firefighter that was unconscious and trapped under the middle of the sign. (2) Roving Engineer/Operator – The individual driving the apparatus was recently promoted to Engineer/Operator and is currently awaiting permanent assignment to an ambulance. Newly promoted personnel in our department are subject to working in a “Roving” status for many months before a permanent assignment is given. This puts them in the uncomfortable and unsafe position of possibly working at a different fire station, with different crews and in different parts of town from one day to the next. (3) Firefighter #1 – This firefighter is normally assigned to another station in another district. He is a 25-year veteran firefighter. He and another firefighter were attempting to raise a 24′ extension ladder when the collapse occurred. (4) Firefighter #2 – This firefighter is a Rookie Firefighter. He was recently transferred to this station. At the moment of collapse, all departmental SOP/SOGs were being enforced and followed. I believe there are several key factors which contributed to this near fatal incident. NOTE: There were multiple points of origin at this fire. It is currently under investigation. (1) Obviously, this crew was not familiar with one another. This particular station and shift does not have a regularly assigned Captain, Engineer/Operator or normal complement of assigned firefighters. The officer is either an Engineer/Operator riding in the Captain position or a Fill-In/Overtime Captain. This is a growing problem/concern in our fire department. One point of concern is the fact that our command staff will fill support divisions such as Dispatch, the training academy and command staff positions, using suppression personnel, before they will fill open suppression positions in the fire stations. This causes a large percentage of fire crews to work with firefighters who are not familiar with one another. (2) Our fire department, like many others, has a chronic shortage of EMS personnel. The command staff has no choice but to require all new hires to become paramedics. Paramedic shortages have always been a problem for our department, but it hasn’t been a real concern to the men and women in suppression until recent times. The concern lies in the fact that a large percentage of our members are eligible for retirement and the men and women promoting into the vacated suppression positions have been lost in the EMS Division for decades. It’s not uncommon for our members to graduate from the training academy, promote to the rank of Captain or above and never fight a fire at any time in between. Therefore, in this case, minimal fireground experience could also be considered. While all of the firefighters on this Engine Co. are viewed as “Good Firemen,” only one could be considered a veteran. (3) Situational awareness and decision-making often go hand-in-hand. Learning how to fight fires correctly takes a long time. It’s not something that most people can simply put on Turnout Gear and figure out what to do. One must learn how to assess an emergency, decide how to deal with the emergency and use the resources available. It’s difficult to make a good decision if you have a limited knowledge of how to deal with the situation facing you. In this case, it would appear that the crew should have considered the possibility of a collapse. But the lack of crew continuity may have been an overriding factor. An officer, or for that matter, any member of any crew, who does not know or have confidence in his/her crew could very easily become overwhelmed with issues as simple as ensuring that the crew hasn’t fragmented and started freelancing. (3) Limited knowledge of the Incident Command System. (See above comments) (4) Teamwork and familiarity of crew members is vital to our safety. The way our shift schedule is designed, we are required to work with firefighters we have never worked with before. Crew continuity is a very important part of safety for firefighters. When continuity is broken, things become very dangerous, very quickly. (5) Our fire department is seriously lacking in the area of training. By this, I mean training in the sense of learning the job. The fire department trains us in basic firefighting strategy and tactics. This training is for entry level firefighting. From the moment we graduate from the training academy, we are at the mercy of our peers and our own willingness to learn the job. This incident was obviously preventable. However, there are many things that we, as firefighters, could be many years in advance of such a situation to prevent such a thing from happening. The Emergency Medical Services has the idea down pat. The EMS Division in any given fire department invests tremendous amounts of money and hours of training just to prepare them for their internship. From there, these EMTs and Paramedics will be assigned to a unit with a Field Training Officer for several months where they go through more evaluation and training. Each one must meet a certain minimum criteria before the division heads will consider turning them loose on their own. On the other hand; a firefighter attends a training academy for a few months. He/she graduates and is assigned to a station. Oftentimes, these Rookies are assigned to an apparatus with a Rookie Captain, a Rookie Engineer and a Rookie riding with him/her on the back of the Engine. That is nothing short of a disaster waiting to happen.

Lessons Learned

1. Training, teamwork, communication and situational awareness are all critical to a safe and successful outcome in every incident that firefighters respond to. 2. All working fires should be followed up with a post mortem. 3. We must always be aware of the possibility of arson. Firefighters must be aware of the common signs of arson: time of day, type of building, location of the building, condition of the building and multiple points of origin, just to name a few. 4. Many firefighters scoff at the thought of being assigned as the Rapid Intervention Team. This is one of the most important assignments that your crew could ever have. Think about it for a moment. If and when you are called into action, you will be assigned the task of searching for and attempting to save a firefighter. More often than not, that firefighter will be a close personal friend of yours. I have been involved in the deployment of two different RITs. At one fire, we lost 2 firefighters. However, at the most recent fire, we were able to save 1. 5. Never assume that you are above learning anything. |

Discussion Questions

1. What were some of the things learned at this incident?

2. What are some things this department could do to improve learning?

3. In what specific areas do they need members to learn?

4. What learning systems does your fire department use?

5. What new learning systems might benefit your department?

Potential Discussion Question Answers

1. Crews were unfamiliar with each other; some crews were unfamiliar with the area; some crews had people in positions they were unfamiliar with; RIT teams are important and an example of learning from the past!

2. Provide more training, a better attempt at keeping crews intact; arrange seniority throughout the department to prevent too many junior people from working together at the same time.

3. Fire training, situational awareness, crew integrity

4. RIT, ICS, Accountability, NIMS, Near-Miss Reporting, …

5. Crew Resource Management (CRM), High Reliability Organizing (HRO)…

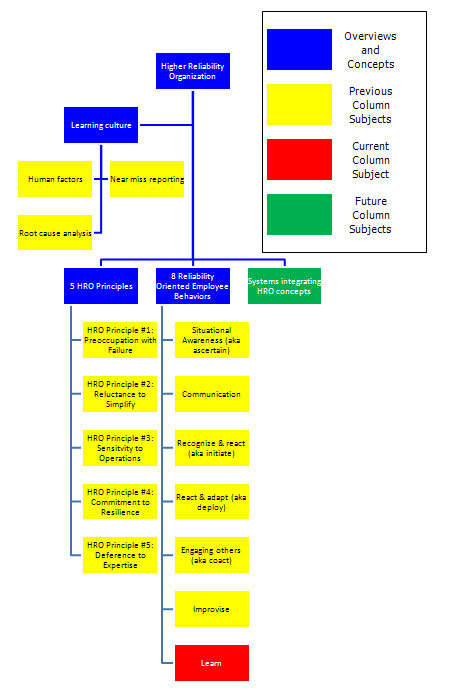

Where We Are Going

Our last article introduced improvise, the sixth of the eight Reliability Oriented Employee Behaviors (ROEBs) developed by Jeff Ericksen and Lee Dyer of Cornell University (2004). Improvising is the ability to use innovative techniques to solve a problem, often a solution stemming from the learning behavior discussed this month. This article discussed the employee behavior of learning, which is the central building block for any organization to be successful. Next month’s column discusses the eighth and last reliability oriented employee behavior of educating. We would appreciate any feedback, thoughts, or complaints. Please contact us at tailboardtalk@yahoo.com or call into our monthly Tailboard Talk Radio Show on Fire Engineering Blog Talk Radio.

References

Ericksen, J., & Dyer, L. (2004, March 1). Toward A Strategic Human Resource Management Model of High Reliability Organization Performance. Retrieved February 18, 2010, from CAHRS Working Paper #04-02: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/9

Oakley, E., & Krug, D. (1994). Enlghtened Leadership: Getting to the Heart of Change. New York, NY: A Fireside Book.

Craig Nelson (left) works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley (right) entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.

Previous Articles

- Tailboard Talk: Write More Rules or Empower Your Firefighters?

- Tailboard Talk: Should Firefighters Train More with Outside Agencies?

- Tailboard Talk: The Fire Service Does This Better Than Anyone, But Do We Recognize It?

-

Tailboard Talk: Is It Freelancing or Showing Initiative?

- Tailboard Talk: Do Firefighters Talk Too Much or Not Enough?

- Tailboard Talk: Do You Really Know What Is Happening With Your Fire Department?

- Tailboard Talk: More PPE or Improved Fire Behavior Training?

- Tailboard Talk: Deference to Expertise

- Tailboard Talk: Not Bulletproof But Close — A Commitment to Resilience