By Dennis L. Rubin

There is an old fire rescue service rhetorical question that everyone asks at some point: Which promotional process is the best one to meet a department’s needs? The identification, selection, and preparation of leaders have a profound impact on all types of organizations – from all volunteer to all career and any combination department in between. How do we go about the mission-critical important business of selecting the very best candidates within the organization to serve as officers? Do we care about identifying the best for advancement into leadership positions? Does the answer reside in selection based on seniority, training certifications, educational attainment, on-the-job experience (acting in the position), or some other type of preparation and testing process?

Perhaps the promotional system should consider a multitude of factors that test for the core traits identified as allowing a member to reach the next higher position within the organization. Can completing a comprehensive job task analysis effectively identify all the skills, knowledge, and abilities that make up the duties associated with being a successful officer? How do politics fit into the selection process for promotion, or should they? Are all these traits important to the success of the newly promoted officer, or are just some of these traits necessary for success?

There always seems to be significant acrimony surrounding this issue. Is it because the impact of leadership is deeply imbedded in every aspect of our departments? No one should take the role of leadership lightly or be unprepared when selected to lead. The leadership position may be sought after because of the personal privilege and reward associated with the higher-ranking positions. Maybe it has something to do with our egos or that some or all of the above drive the desire to get and keep promotions.

Of course, the promotional system that everyone seeks is or should be based on fairness (without bias), transparency, honesty, validation, effectiveness, and efficiency. This is a very difficult question to answer by some, because there are a lot of personal values, traditions, and beliefs that creep into deciding on the promotional process to use. Sometimes, the question of the best promotional system gets a bit “cloudy,” to say the least.

After studying this process by conducting years of “practical applied research” through preparing, implementing, and evaluating many promotional tests for all ranks, we have developed a nonscientific response to answer the question, “Which is the best promotional system?” Most will not like this hypothesis, but the closest to the truth is that there is only one predominant successful selection process used to identify leadership talent. The only promotional system that is fair, honest, and effective and that truly identifies the best person for the position is the system in which I get the promotion. This is such a sad, controversial statement to make, but it seems to be an accurate one. If I get promoted, it is a great system! If I don’t get the job, the system was flawed.

But, the “How could you not promote me?” reaction has a lot of merit, if you will reflect on observed behaviors. When a person gets the next position up the chain of command, he is ecstatic to pin on another speaking trumpet or change the badge finish from a silver to gold on that breast badge. Happy describes the affective attitudes when the promotional list is published for those who will or will very likely get promoted.

In stark contrast, the folks who do not receive a promotion will not be very happy at all! In fact, they can exhibit reactions from mild concern to uncontrolled and overt anger. The range of challenges to the selected testing process can be as narrow as taking no action to protesting a single test question to civil lawsuits seeking millions of dollars in compensatory and punitive damages. At times, the demonstrated behaviors have the appearance of entitlement for promotion. The poorly performing promotional candidate feels strongly that he should be promoted regardless of the process. Some of the flawed rationale that has crossed the chief’s desk has included the following: “because I have the most seniority,” “I have acted in the position as a provisional officer the longest,” “the promotion should be mine based on my education attainment,” “I have passed the silly test and I am the senior member,” and the list goes on.

A Demonstrative Case Study

A few years ago, 28 angry white fire captains filed a claim that the fire chief promoted only black members to the rank of chief officer. The judge allowed the case to go forward in a federal courthouse based on the rule of law that the civil complaint was focused on discrimination and not on the promotional process used by the department (which was at the fire chief’s discretion). The facts in the case were that during the 5½-year period in question, the fire chief had promoted 21 members to the rank of chief officer. The racial makeup of the pool of members selected for promotion was 11 white members, nine black members, and one Asian-Pacific member.

Although the judge’s intention was to keep the focus on the discrimination issue, many comments were made about the appointment process to promote into the chief officer positions. Time in grade as a captain, time spent acting out of class, and time in the department were all mentioned as distinguishing qualities for being the reason that the class of 28 should have been selected for promotions. The closing defense attorney argued, among many other issues, that there were not enough open positions to elevate all 28 white captains if all were the best qualified candidates during that period. Of course, other important issues, such as performing poorly on the testing measurements that were used, were pointed out as well.

The result was that the plaintiffs’ claims were determined to be unfounded and denied by the jury of their peers. Considering the facts in this case study – 28 people demanding promotions into 21 available positions – lends credence to the belief that the only promotional system that works is the one that gets me promoted.

Insulate Your Organization

Effective communication with all involved early on will help build trust and understanding of the process being used to make the selections. Conduct organizational communication that builds interpersonal relationships to “soften the expectations” of the entitlement group; not everyone will be promoted. It will take a while, but you can expose the “it only works well if I get promoted” folks to the reality of the situation.

The best place to start is with frank discussions during the recruitment, selection, and orientation processes. The discussion should focus on the reality of the numbers of positions vs. the number of successful candidates to fill those positions at any given time. All members should be motivated to do their best and perform at the highest level that they can achieve. Be a mentor to everyone who wants to improve their value to the organization; just make sure there is a dash of reality added to the discussions.

A great example of overall organizational preparation is a program that Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini developed. It consisted of a remarkable booklet that he called “The Phoenix Way.” This document was a comprehensive review of the expectations and the accountabilities of all members of the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department. Coupling that type of cultural education with a detailed presentation on how the promotional system works, what to expect, what components are used to test for promotion, and what constitutes being properly prepared should go a long way to decrease the complaints and deliver a positive impact.

The Military Promotional Model

In the United States Armed Forces, a second lieutenant will often hear that it is “up or out.” The concept is that military officers must continue up the promotional path or they will be separated from service. It sounds a bit harsh, but the need for high-quality leaders during combat cannot be overemphasized.

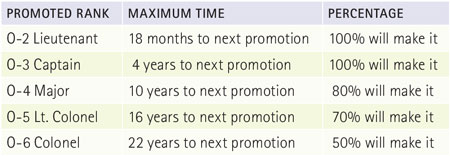

The officers’ ranks are classified as O-1 (second lieutenant) through O-10 (four star general). There is a mandated timeline to reach the next level of promotion (see chart below).

If the aspiring officer fails to make the next rank at or before the maximum time allowed, it is time to start a new career; his military service has been completed. Another interesting part of the process that the Armed Forces uses for promotions is the “pass over” rule. The second time a qualified officer is passed over for promotion, separation from service is not far behind. Of course, the “up or out” and “pass over” processes would not align with most labor contracts, personnel regulations manuals, or civil service procedures.

Promotional Considerations

Most departments start the promotional quest with a list of the prerequisite requirements. These items are personal attainments that must be acquired by the member (typically with support by the department, but the motivation comes from the member candidate) to be considered for promotion. The prerequisite list serves as the gateway for moving up the corporate ladder, focusing on being prepared to reach the next higher rank.

The typical list of factors considered includes but is not limited to the following:

- Minimum number of years of service in the department.

- Minimum number of years in rank or grade.

- Minimum training certification requirements (i.e., Fire Officer I).

- Minimum formal educational requirements (i.e., AAS degree).

- Work history performance and annual work evaluations.

Once the minimum prerequisites are reached, the department will typically apply the various test methods and measurements to determine who is ready for promotion and who is not. A wide array of test measurements can be used to determine the “readiness” of a member to take on more organizational responsibilities.

Written testing is a typical promotional test measurement that is composed from a list of materials that the candidates are given to prepare for the promotion. Examples include fire-rescue textbooks as well as internal documents such as policy, procedures, and operational guidelines. The test format could be multiple choice or essay. There is a grade scoring rationale that is assigned to the written testing process that is usually not above 50 percent of the overall scoring rubric value. Most written test measurements are administered early in the selection process and serve as a “gatekeeper” for the member to continue to move forward. A popular standard often used is that a minimum written examination score of 70 percent serves as the pass-fail cutoff point. Regardless of the cutoff score you select, do not change it in midstream. If you lower the score to qualify more candidates or raise it to eliminate members, you will lose credibility and receive an invitation to appear at a formal appeal hearing or perhaps get a chance to visit the local courthouse to explain such behavior.

Consider engaging the services of a well-known, highly capable, and reputable consulting firm to prepare the written test measurement. This is recommended for several reasons. The consulting firm will provide more control and confidentiality over the test development and implementation process. The last thing a department needs is to have a rumor circulating about the “chosen few” obtaining the test questions ahead of time or that the written test was compromised. Using an outside firm will not guarantee test security but is a great start toward making a “loud” statement that test quality and reliability are important to the organization.

The assessment center process is typically implemented after candidates complete the written test measurement and receive a “passing score.” The next part of the advancement selection system is to attempt to offer test measurements that are realistic and relevant to the performance of the required job skills for a member to be successful in the position. Assessment centers often open with an “inbasket” examination exercise. The inbasket station tests a wide variety of supervisory skills including writing, prioritizing, and policy comprehension. There are dozens of other assessment center test methods such as oral interview and command and management simulation to determine a person’s readiness for promotion.

One critical but often overlooked step in assessment center development is to perform a comprehensive job task analysis with all incumbents in the class (rank) to determine the needed skills, knowledge, and abilities (job dimensions) to be successful while serving at that level. Unless you have a capable human resource department, this work might also be best completed by an outside consulting firm. This is the type of administrative effort that a department gets a single chance to get right. The consequences of failure while implementing any part of a fire department promotional system are severe, swift, and long remembered.

Never Promote Idiots, Thugs, or Military Misfits

Implement a background check as a member draws close to moving up the ladder. Some departments have ongoing personal background reviews; they are to be applauded for their efforts. However, most agencies place a member through a rigorous review just before a job offer and entry into the department. Once the member is in the organization, the background check is never completed again. Perhaps more frequent and ongoing background review would prove to be useful and help keep undesirables out of higher levels of authority. Nothing is more embarrassing than for a department to learn that the person is a child molester or a spouse abuser after the person was promoted.

Medical and physiological health testing will ensure that the member selected is fit for duty. Both mental and physical health should be major concerns for all departments. The stark reality is that one-half of all firefighters who die in the line of duty die of a medical condition such as heart attack, stroke, or cancer. A comprehensive fitness program is a must to properly manage a fire department. If health and wellness are associated with the members’ ability to obtain promotions, compliance to the wellness program will increase and better organizational health will surely follow.

A Modified Up or Out Philosophy

Seniority points are usually added to a member’s promotional score card once all test measurements are completed. There is a wide variance in the calculation and application of seniority points. Some organizations weigh time in grade as a large aspect of being prepared for the job, while others place only a small value on the experience gained on the job.

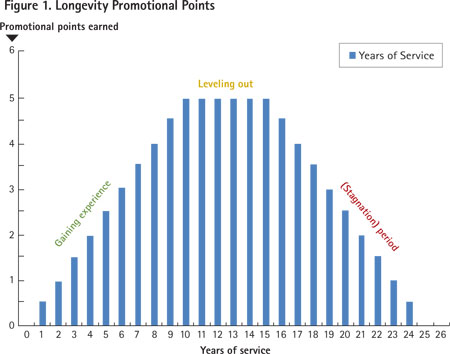

One suggestion is to add 0.5 points per year for the first 10 years of service. Once the member reaches the 10-year mark in grade, five promotional points are added to the testing total scores. Here is the twist: Once the member reaches the 10th year of service in the same rank, there is no increase in promotional points for the next five years. Starting at year 16 in the same rank, the promotional point decreases at the rate of 0.5 per year. At the member’s 21st year in grade (rank), the total seniority points would reflect zero. Figure 1 illustrates the longevity promotional points scaling up to five, plateauing and staying at five for an additional five years, and the decline of these points all the way to zero for failing to get promoted within the 15-year window. As a member reaches the next rank, say a fire lieutenant is promoted to fire captain, the time in grade points calculations starts over, with five total points available for 10 to 15 years of service in grade.

Commitment

You need a structured method to evaluate a member’s “organizational commitment.” Some folks put the least amount of effort into their careers; others demonstrate organization commitment every day on the job. Promotional value needs to be placed on the additional activities that are above and beyond the day-to-day required duties. There are many ways for a member to demonstrate dedication and commitment to the department. This excellent behavior should be acknowledged and rewarded in some significant and meaningful ways.

A few of the ways to outwardly demonstrate the commitment to the job include but are not limited to the following: serving on committees (such as apparatus design and purchase), obtaining professional certifications, seeking advanced education, accepting a daywork position for two years or more, and performing community service (local rotary or other civic club).

Overhaul Needed

The promotional system most fire departments have can use an overhaul. This is a step toward continuous and ongoing improvement of the promotional process. The military model of recruiting, retaining, and promoting men and women into leadership roles perhaps could fulfill our needs. The Armed Forces’ practice of “up or out” has a lot of merit and needs to be explored and refined further to be applied to our profession. There are many hurdles, such as civil service policies and labor agreements, that would need to be adjusted to allow this action to happen.

Just being in the firehouse the longest doesn’t cut it anymore. Much like the escalating and declining seniority points scale, it is time to make these needed changes to produce the best officer selections possible.

DENNIS L RUBIN, a 35-plus-year veteran of the fire service, is principal partner in the fire protection consulting firm D. L. Rubin & Associates, which provides training, course development, and independent review of policy and procedures for all types of fire-rescue agencies. He has a BS degree in fire administration from the University of Maryland and an AAS degree in fire science management from the Northern Virginia Community College. He is a graduate of the NFA Executive Fire Officer Program and the Naval Postgraduate School’s Executive Leadership Course in Homeland Security. Rubin is a certified emergency manager and incident safety officer; he has the Center for Public Safety Excellence Chief Fire Officer Designation (Inactive) and Chief Medical Officer Designation. He has been an adjunct faculty member at several state fire-rescue training agencies and the NFA. He is the author of Rube’s Rules for Survival, Rube’s Rules for Leadership, and D.C. FIRE.

Dennis L. Rubin will present “It’s Always About Leadership” at FDIC International in Indianapolis on Wednesday, April 26, 2017, 10:30 a.m.-12:15 p.m.

Hiring and Promoting for the Metaphoric Bus

Promotional Assessment Center Preparation

Prepare for Your Promotion Now!

Fire Engineering Archives