BY LES BAKER

On March 7, 2008, two firefighters from the Salisbury (NC) Fire Department were killed when they were trapped by rapidly deteriorating fire conditions inside a millwork and manufacturing facility. During the aftermath, several department members visited the Charleston Fire Department (CFD) to shadow personnel in various divisions with the intent of observing a department that had endured a similar tragedy (the Sofa Super Store fire on June 18, 2007), faced internal and external review by countless agencies, and was instituting changes on multiple organizational levels. During their time at the training division, they were taught a little known drill that involves tires laid out in a grid and the broad spectrum of potential lessons that could be learned from navigating between them. From that event, the Nine Tire Drill evolved into a necessary component of our recruit class curriculum as well as that of the South Carolina Firefighter Survival School.

Author’s note: Portions of this article were contributed by members of the Charleston Recruit Class 1201, “Fortitude of Mind.”

ABOUT THE DRILL

|

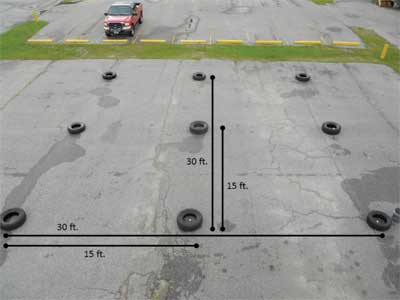

| (1) The initial setup for the Nine Tire Drill. |

The Nine Tire Drill is not designed to teach basic search patterns and, on the surface, could be perceived as an easy drill with little fire service relevance: The participant simply crawls around in a parking lot. However, it can be used to teach a single firefighter or a crew of firefighters valuable lessons in orientation, self-preservation, air consumption, tool handling, area mapping, and other skills.

One recruit with no previous fire service experience stated, “The first recruit I witnessed had years of fire service experience and entered the course very confident in his plans and abilities. I believe it was after the second tire that he was about 20 feet off course and getting worse by the second. The lesson I learned from him was, don’t underestimate this thing.”

|

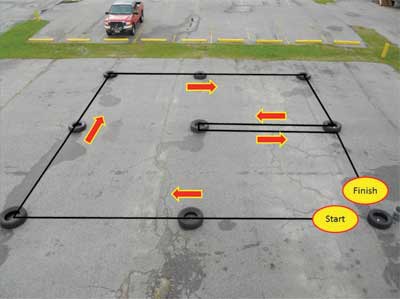

| (2) Although participants were not required to follow a particular pattern of movement, the arrows depict the “typical” path taken by most participants. (Photos by author.) |

Another recruit stated, “Hollywood portrays firefighters standing and rushing through fire to easily rescue victims. However, this drill teaches you the value of making calculated movements and taking in every piece of information available to avoid disorientation. I got lost several times in a 900-square-foot area with no obstructions or added stress. I can only imagine what the consequences would be in a building two, three, 10, or even 20 times bigger.”

As an example of the potential magnitude and the relevance related to the recruits from our history, the Sofa Super Store was a one-story, commercial furniture showroom and warehouse facility totaling more than 51,000 square feet. After several renovations, it incorporated mixed construction types with aisles of furniture and metal shelving.

The drill takes very little resources and almost no time to set up. It can be held anywhere, making it a great option for all fire departments.

|

| (3) This firefighter navigated the tires and is assembling the PVC pieces.” Click to view video |

Setup

- Set up nine tires, 15 feet apart, in a three-by-three grid. You can substitute rolls of hose for the tires.

- Place in the tires pieces of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe, such as short pipe, elbows, end caps, and tees, which the participants have to collect while navigating the grid and put together in puzzle-like fashion after they have finished negotiating the grid. Note: Prior to the drill, show the participants what the pieces will look like after they have been constructed into a puzzle.

- Participants don full personal protective equipment including their self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) with the face piece blacked out to achieve no visibility.

- Participants should have with them a tool of their choice or one that has been assigned to them based on their riding positions.

- Position the firefighter at the first tire facing toward the second tire. Note: Make sure that the firefighter understands which tire he is facing to prevent any early confusion related to the direction of travel.

- The participant navigates through the grid, retrieves all the PVC pieces, returns to the starting tire, and assembles the PVC pieces.

|

| (4) The firefighter is holding the assembled “puzzle.” |

LEARNING POINTS

Following are some learning points and suggestions for participants and instructors:

-

Navigation. Move and navigate systematically-row by row or outside edges first and then the middle. Maintain a smooth pace that allows you to finish in a reasonable time and maintain orientation through critical thinking skills. If you become lost, you will be in an almost helpless situation.

The instructor can attempt to help piece together the participant’s location; however, many times, the participant has to be restarted or placed on a tire and directed toward the next tire. - Timing. Participants’ fastest completion times without instructor assistance have been under seven minutes. Participants with the longest times ran out of air because they had to be restarted several times. The drill is purposely a timed competition to facilitate additional stress and show the effects of not pacing oneself. To equate this to the fireground, interior operations should be conducted with urgency and pace but not so fast that safety is jeopardized.

- Air consumption. Timing the drill not only serves to create a competitive and, therefore, slightly more stressful environment, but it also enables you to document air-consumption rates, which impact the duration of the air supply and can help firefighters and fire officers to balance the needs of the incident or assignment. Regular and effective training exercises with the SCBA can deepen an understanding of the interrelationship of the air consumption rate, the incident, and the team members. The Nine Tire Drill is a great opportunity to document a rest to moderate the work load. Once the participant has finished, compare the completion time with the amount of air used during the drill.

-

Preplanning. Preplanning the area prior to beginning the drill helps the participants to remain oriented. Advise them to take advantage of any ambient clues. In some cases, several recruits identified otherwise unnoticeable details, including more pebbles in certain areas, potholes, small grassy areas, nearby props and parking stops, noise from heavy vehicles and interstate traffic, and sun direction, as helpful in their mapping process. One recruit noted: “The fire has no rules, and we should use every advantage possible. In survivor mode, there is no such thing as cheating-only doing your job, rescuing lives, and taking care of yourself and your crew.”

A lot has been published recently about “mental mapping” and creating an image of the room as it is navigated. This process should begin prior to the incident with preplanning. A preplan will allow you to look at the layout of buildings and give you some landmarks to keep in mind if you were ever lost or trying to navigate the structure in limited visibility. We are also allowed into many peoples’ private homes. Whether you are there for a medical call or to install a smoke alarm, look around. In many neighborhoods, houses share similar construction characteristics. - Stimulate the learning process. Continually ask the participants questions throughout the drill: How far have you traveled? What is the quickest way back to the beginning? How long have you been on air? One recruit reported: “About halfway through, I was asked by an instructor, ‘How many pieces do you have?’ My world stopped; my head spun because I knew I had six, or did I? I thought it was a trick question; then I quickly realized, What if that question was how many doors did you pass, or how many left-hand turns did you make?” Depending on how challenging the instructors want the drill to be, they can ask the students a rapid fire of questions to try to throw off their concentration.

-

Forcible entry tools. They can be used in a traditional search to extend reach; in this case, they can be used to locate the upcoming tires. Yet, it is surprising to see how many participants never transfer the tool to the other hand to increase the diameter. If the student extends the reach with one arm by using the tool and repeats the process with the other arm, he can effectively scan an area up to 15 feet wide.

The instructor should emphasize that the participant should not lose contact with the tool during the drill. If at any point the participants are using both hands to manipulate the pieces, the participant should capture the tool with a leg or a foot. In addition, the tool can be used as a directional tool by positioning the tool at each tire in the direction to be traveled or the direction from which the participant came. A recruit explained, “Since I started a search on what I thought was the outside perimeter of the square, I knew that if my tool hit the tire from a sweep left to right, I was on the outside of the course.” - Since participants’ vision is obstructed in this exercise, participants should elevate their other senses to compensate for the loss of vision. Relying on the sense of feel can be difficult at times if you lack dexterity, but firefighters should notice major changes in floor coverings, pieces of furniture, doors and windows, and so on. As one recruit noted, “For example, during a search within a residential structure, you begin your search in the kitchen by the rear or side door and advance to the next room, where the surface has changed from a hard surface to a soft carpeted area. You should understand the change in texture and use it to assist with orientation.”

The sense of hearing could help identify things such as ventilation, water, alarms, generators, and sounds of particular apparatus. Being able to establish two or three sound locations makes it easier to triangulate positions. Ultimately, participants should compare what they feel and hear with what they noticed during the preplanning phase to make sure mapping and the current location are consistent. - Participants should understand their tendencies when it comes to crawling. Most people are able to determine approximate distance based on their walking stride. Firefighters should be familiar with the distance they cover while crawling, whether it is a conscious or a subconscious process. Firefighters also have tendencies related to direction. Some drift off course depending on their dominant side; others may drift toward or away from the hand maintaining contact with the tool.

VARIATIONS

You can make this drill as complex as you wish. As participants become more familiar with it or observe others, it may be necessary to increase the difficulty level. Several options are available.

|

| (5) A participant used his tool to mark the direction of the next tire before committing himself to retrieving the PVC part from the tire. If a department wishes, it could have the instructor carry the bucket, but maintaining the bucket adds an additional level of stress. It could be compared to carrying additional equipment, such as a water extinguisher, a rapid intervention team bag, or a search rope, on the fireground. |

- Spread the tires farther apart and conduct the drill in groups of two. This will necessitate increased coordination and communication between two participants.

- Give a company officer limited visibility and have him guide a firefighter through the course to simulate giving directions through a thermal imaging camera.

- Place an additional fire service object in the tires. During the navigation of the tires, participants must remember what objects are in each tire and, once all the pieces of PVC have been gathered, return to whichever object is called out by the instructor.

- Turn the drill into more of a search drill by placing objects within the grid for participants to locate while they are navigating.

The Nine Tire Drill reaffirms the need to adhere to basic firefighting principles, including searching systematically to increase efficiency, staying alert, pausing occasionally and holding your breath, and maintaining contact with a hoseline or a tagline when visibility is obscured. However, more than anything else, it demonstrates the potential to become easily disoriented during interior operations, a common contributing factor in many firefighter injuries and fatalities. Without total concentration throughout the Nine Tire Drill, just as when navigating in an immediately dangerous to life or health atmosphere, it takes only one second to miss something important and potentially get disoriented. Firefighters’ efforts to remain oriented should begin before an incident by becoming familiar with their response area, continuing a thorough ongoing size-up, and developing them further during the interior operations. Maintaining orientation should be an evolving and constant process that guides interior crews through typical operations and planning for unforeseen events. Unfortunately, we cannot control every single factor on the fireground, and an inherent risk is always present. A recruit summed it up best: “You have to understand that things are going to occur spontaneously, and it’s how you react to those spontaneous occurrences that can save your life.”

LES BAKER, a 17-year veteran of the fire service, is an engineer with the Charleston (SC) Fire Department. He has a B.S. degree in fire science from Columbia Southern University. Baker is an adjunct instructor with the South Carolina Fire Academy and a member of the Darlington County Extrication Team, and he speaks and instructs throughout the country. He is the creator of Speed Simplicity Boldness, which provides relevant and high-energy training to emergency responders.

Fire Engineering Archives