Our meters are killing us

Next to “All clear on primary search” and “Fire under control,” there are probably no words dearer to a firefighter’s heart than “All clear on SCBA (self-contained breathing apparatus).” Although great strides are being made in the comfort, weight, and fit of our SCBA, they remain one of the single largest sources of physiological and psychological stress we face in day-to-day operations. We anxiously look forward to the instant when we can remove them and “breathe easier” and work in greater comfort. For those of us who are older or not quite in the physical condition we should be, this is especially true! All other things being equal, cardiovascular conditioning is most often the limiting factor in tolerating long work cycles in SCBA.

At a recent fireground operation, even prior to having a secondary search completed, the battalion chief was heard to ask the safety officer, “Get me an all clear on SCBA as soon as you can.” Obviously, it was a high priority to him, as he “looks out for his guys.” But, just exactly what are we basing that seemingly critical “all clear” on?

Currently, some departments base it on initial knockdown (fire under control), others on the initiation of overhaul (loss stopped), and others on simply a wild guess-“It looks clear.” The more progressive departments are seen using seemingly “scientific” benchmarks usually based on Occupational Safety and Health Administration threshold limit value/time-weighted average such as less than 30 or 35 parts per million (ppm) carbon monoxide. Those departments that are really seen as “tops” use a four- or five-gas meter so that they can also add in things like less than five ppm hydrogen cyanide and values for volatile organic compounds, hydrogen sulfide, or some other “poster child” fireground gas. How about ultra-fine pyrolyzed carbon? Does your meter register that? Pyrobenzene? Fiberglass? Asbestos? Phosgene? The list for what your meter does not measure is almost endless, and many of these substances are at least as toxic as, if not more toxic than, those we do sample for!

I maintain that we are absolutely fooling ourselves at the cost of an entire generation or two of firefighters dying to cancer by using these readings. Our meter, or at least our reliance on it, is killing us! There are several hundred toxic gases produced on a fireground; most are generated at different stages of the combustion process. The poisons produced during the free burning phase are radically different from those produced during the overhaul phase. Yet, we will walk through with our expensive meter and declare the fireground “All clear for SCBA” (i.e., safe) based on sampling for only two, three, or four of the many thousands of chemicals we will be ingesting when switching from purified breathing air to the toxic soup of the fireground.

Do you want to go on a hazmat call involving anhydrous ammonia with only a chlorine meter and tell your crews they’re okay? How about telling your crews that they’re safe for a confined space entry based only on flammability and oxygen levels? Unconscionable! Yet because of our mindset, we routinely, and without thought, do this on fire calls.

My personal epiphany came several years ago while on a seemingly “routine” residence fire. At a “vinyl village,” we’d had a significant fire that burned off most of the roof of the house. While assigned to overhaul, pulling down what little remained of the ceiling and looking at blue skies above us, the safety officer breezed through with his meter that cost a couple of thousand dollars. He radioed back to the incident commander, “CO 10 ppm, HCN 0 ppm, H2S 1 ppm. We’re all clear on SCBA.” You could barely see from one side of the room to the other for the shimmering haze of fiberglass particles hanging in the air, glistening in the sunlight, streaming through the missing roof.

They billowed each time we pulled a bit more ceiling down and dumped another load of insulation to the floor. He exited, and my rookie started to immediately pull off his mask. I cracked him in the arm with the closet hook, knocking his hand away from the mask. The response from my back-stepper was, “What? He said it was all clear!” My reply was, “Does it look ‘All clear’ to you?”

We are becoming technologically blind to the dangers of the fireground because we rely on only a few data points to assess our safety. It should not require a multipage research paper with impressive-looking citations and annotations and rife with scientific jargon to impress on firefighters that there is nothing healthy about breathing fireground air!

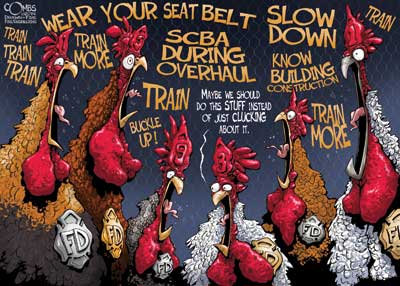

In many respects, chronic exposure-the many hundreds of “little doses” of toxins we take in at the fireground-are worse than an acute exposure because of the insidious belief that we can tolerate “a little poison” and will recover from it with no ill effects. Acute exposures are self-limiting; a breath or two, and we’re out of there. We are willfully and woefully blind as to the effects of the accumulated dose. It cannot be a coincidence that cancer rates are through the roof in almost every fire department in the country. It will take strong leadership and an unpopular policy if we hope to make a dent in what is rapidly becoming the leading cause of death among firefighters. There should be no such thing as “All clear for SCBA” until you are putting your gear back on the apparatus to leave. If that takes calling an extra crew (or two) to the scene to assist with overhaul or longer rest cycles between assignments, then that is what it takes.

Firefighters are the masters of “what if” arguments. “What if another call comes in while we’re delayed at the fireground because of overhaul?” “What if it wears me out too much to keep the SCBA on that long?” “What if another crew isn’t available?” And the unspoken one I believe is behind much of it, “What about being teased or not thought of as ‘tough enough’ because I keep my SCBA on and others don’t?” The response would be best put in terms of risk analysis. Which threat would you want to face, missing the chance (however slim) at a second call or facing the near certainty of having to deal with cancer? That meter is used only to advise the property owners of the risks they face when they resume control of their property. We can be in absolute control of the exposures to the many hazardous materials we encounter on the fireground if we choose to be.

Jim Campbell

Division Chief of Training & Safety

Pike Township (IN) Fire Department

Goal is to advance safety

In reference to “The Fire Service: 250 Years of Driving Progress” (Editor’s Opinion, October 2013), Chief Bobby Halton’s comments on how to perceive the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) are accurate, but he balanced them by highlighting critical improvements in firefighter safety NFPA standards have made possible. The team here at the Public Fire Protection Division, all responders themselves, appreciates his words and highlighting the good we do.

As always, we are here to assist Fire Engineering and the Fire Department Instructors Conference in advancing responder safety and knowledge.

Ken Willette

Division Manager

Public Fire Protection Division National Fire Protection Association

Transitional fire attack

Scenario: On arrival, you discover a one-story, single-family residence with fire showing from a window on the C/D corner. After a 360° size-up, an aggressive interior attack is initiated from the front door on side A. On entry, you have heavy smoke from floor to ceiling, and you are having a difficult time getting to the fire. Five minutes soon elapse, and still no fire. Command is requesting updates and notifies you that the fire has extended to the attic and the roof. The temperature begins to rise rapidly. Then the almost shameful announcement comes over the radio from command: “Emergency evacuation! All companies evacuate the building!” On your way back to the door, you hear the blast of the air horns signaling that you should evacuate. All companies are out of the structure and exterior lines are placed in operation. After the knockdown is completed, command orders a secondary search. Your heart sinks as you realize a primary search was not completed because you were unable to reach the seat of the fire. Luckily, this time, no victims are found. You and your crew gather at the tailboard and begin the process of trying to determine what went wrong.

Unfortunately, I have had this experience. According to studies by Underwriters Laboratories (UL) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a quick knockdown of this fire from the exterior would drastically improve the chance of victim survivability and decrease the possibility of flashover. With this scenario and these conditions, a transitional fire attack should be a mandatory standard, not just an option.

For more than 24 years, I have trained on and used aggressive interior tactics. When I first learned of the outcomes of the UL and NIST studies, I was quite upset. However, because of the scenario above and other experiences, I can relate to these studies. I no longer have an argument. From this information, we have learned that flowing water from the exterior is the most aggressive and life-saving tactic we can perform when conditions permit. The decision to use this new tactic is based on time. What is the quickest means of applying water to the fire? Will it be interior or exterior? Obviously, if no fire is visible on arrival, then an aggressive interior attack should be initiated. Get the nozzle to the seat of the fire as quickly as possible. If fire is venting from an opening, then an exterior application will usually be the quickest route.

Our department recently implemented a transitional fire attack standard operating procedure (SOP). Its purpose is to rapidly improve conditions for trapped victims and reduce the risk of injury to firefighters. It will be initiated on structure fires that have fire venting from an opening that is readily accessible on arrival. The officer in charge will announce over the radio that this tactic will be used. The SOP calls for the use of a smooth bore nozzle at a steep angle toward the ceiling flowing for 15-30 seconds. The nozzle is to be held in the center of the opening to allow steam to vent. After knockdown is achieved, a transition to an aggressive interior attack to the seat of the fire will be initiated.

If we continue to rely on and allow interior-only operations, are we doing our best for those we serve? Can we be held negligent for not implementing safer tactics that we know are available but decide not to use? A transitional fire attack should be a required standard procedure, not just an option.

Brian Fraley

Acting Chief

Clinton Township (OH) Division of Fire

Fire Engineering Archives