By Jerry Knapp and Dan Moran

In “Improving Your Natural Gas Response Procedures” (Fire Engineering, March 2017), we examined the critical background knowledge you need to fully understand strategic and tactical considerations associated with response to natural gas emergencies. Most importantly, we stressed that our fire department procedures should include a “life safety first” policy, be based on procedures, and closely mirror gas industry best practices. The concept of the “kill box” was introduced to remind officers and members of the need for a proactive safety posture to guard against complacency. (Kill box refers to the area around the building in which responders likely would be killed or injured if a gas explosion were to occur. You may be hit with flying glass, other fast moving parts of the building, or even falling energized wires. Luck, faith, or fate will determine if it means certain death.) Case histories reinforced just how quickly and deadly “routine” gas leaks can become.

This article examines strategic and tactical issues that must be considered to effectively and safely mitigate common gas leak situations. You may want to compare the information in the article with the contents of your standard operating procedures (SOPs).

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto1.jpg" alt="(1) The house before the explosion. [Photos 1-2 by Chief James Comstock, Henrietta (NY) Fire Department.]“> |

| (1) The house before the explosion. [Photos 1-2 by Chief James Comstock, Henrietta (NY) Fire Department.] |

There are six basic types of gas leak scenarios: third-party damage, outside odor, inside odor, locked building, explosion, and leak with fire. Your gas response procedures generally can be based on these scenarios. This, of course, is not to say you should blindly follow the protocol.

You get paid to observe, analyze, think, assess, size up, and develop a plan specific to the scene. Your plan must be based on a solid general procedure in your department SOPs. The senior leaders in your department are responsible for ensuring that your department has an effective, safe general response protocol.

We have found that many fire department gas response SOPs are not procedure based and propose actions that should and should not be taken (basic do’s and don’ts). They often provide some basic information, but they are not proactive and essentially leave the junior officers on the first-due rigs to figure out policy and procedures for themselves. Senior leaders must establish policy and procedures based on gas industry best practices. Your SOPs should be appropriate for your local conditions and be aligned with your local gas company’s response policy and procedures.

Let’s look at strategic and tactical objectives for common scenarios.

Third-Party Damage

This scenario results when gas system piping becomes damaged and causes gas to release.1 In Henrietta, New York, on February 1, 2016, a homeowner struck his gas meter while pulling his car into the garage attached to his home. Henrietta Fire Department (HFD) Lieutenant Tom Hayes, one of the first three firefighters on the scene, said he smelled natural gas and heard the hissing sound of a leak. The utility was called immediately. As Hayes began to walk with the homeowner away from the house and up the street toward a car where the homeowner’s wife was waiting, the house blew up. The front of the structure was clear. Hayes said the blast went out the rear of the structure; that was where most of the debris was. The explosion occurred within two minutes of the firefighters’ arrival on scene.

This incident didn’t involve loss of life because the HFD took “life safety first” actions and did not try to stop, investigate, or fix the leak. If Hayes had investigated the leak or attempted to shut off the gas, he, his crew, and the occupant could have been injured or killed.

Good policy and procedures led to a good outcome. Stress “life safety first” in your policy and procedures, and adhere to best practice response procedures; it is a matter of life and death.

|

| (2) A view of the house after the explosion. |

Another common form of third-party damage is usually caused by a backhoe, an excavator, or a homeowner with hand tools damaging a service line to a home or a gas main in the street. A contractor or the homeowner could be installing or repairing other underground utilities, a fence, or a driveway or planting a tree.

The mistake we often make at these calls is assuming that all the leaking gas from the damaged pipe is escaping upward into the air. If this were the case, there would be little danger unless the gas enters an open window or door and accumulates and an ignition source is present. Natural gas is lighter than air, so it will typically escape and dissipate until the utility can shut it off.

Frequently, the backhoe or excavator bucket has pulled the gas line while taking a scoop of soil out of the trench. The operator quickly realizes this and abruptly stops the movement of the bucket. Gas is escaping near or into the open trench near the bucket. This stress/pull on the line may have caused the pipe to be damaged and leak inside nearby buildings. Some gas is escaping directly into the atmosphere, but significant amounts may be leaking into the building from damaged pipes. Never assume it is all going harmlessly up from the trench. The soil in the trench may be dancing as it is being sprayed up in the air by the gas pressure. If there are trees or shrubs near the trench, look to see if they are being moved by the escaping gas. These observations may give you some idea of the volume and pressure of the leak.

Follow the strategy of life safety first and get the occupants out of the endangered buildings; then try to determine the specifics of the leak, damage, and possible migration of gas.

Underground Leaks/Outside Odor of Gas

This is the most insidious type of gas leak. You can’t see it, and you don’t know where or how extensive it is, but it is your job to protect civilians and firefighters. It may be sneaking underground beneath your feet. We often get these calls as an outside odor of gas. We don’t give these calls the respect they deserve. Underground gas leaks are nothing new; neither are the hazards to firefighters.

On January 24, 1970, an underground gas leak in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, injured firefighters and public safety officers. The alarm began as a reported house explosion. One house was destroyed, triggering a second- and a third-alarm mutual-aid response. A 65-foot aerial platform was put in service about 30 feet above the ground to extinguish the free-burning home. The fire was knocked down in about 20 minutes.

There was a heavy odor of gas, and one additional home exploded without any subsequent fire. This was followed by a second blast, which involved the elevating platform. The explosion below street level raised the left side of the truck 1½ to two feet off the ground. The whiplash of the upper boom tossed one public safety officer out of the basket. He landed clear of the debris in a snow bank. It is estimated he fell 30 feet. A corporal, who was also in the bucket, was seriously jarred but was not thrown clear. The other two crew members were stunned by the force of the explosion.”2

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto3.jpg" alt="(3) A backhoe bucket pulled a gas line during trenching operations. (Photo courtesy of the New York State Department of Public Service.)“> |

| (3) A backhoe bucket pulled a gas line during trenching operations. (Photo courtesy of the New York State Department of Public Service.) |

Operations continued with the rescue of the seriously injured bucket operator and others as gas-fed fires ignited through cracks in the pavement. The overriding life safety and size-up considerations at incidents involving underground leaks or an outside odor of gas are the following: Is the gas migrating underground and into nearby structures? Are lives in danger? How do you meet your responsibility of life safety first?

The first step is to have the right mindset: Plan for the worst and hope for the best – in other words, give the call to this leaking explosive gas situation the respect it deserves. If gas gets trapped in a closed building that contains numerous ignition sources, the results could be equivalent to the blast of a big bomb. We call buildings with gas and ignition sources improvised explosive buildings (IEBs). The worst case here would be gas migrating through the soil, underground sewer, drainage, or electric or plumbing conduits into the nearby buildings. This strategy (presize-up assumptions actually) will guide you in quickly estimating and identifying the kill box, keeping the rig out of the kill box, keeping as many members as you can out of the kill box, and immediately starting to identify those buildings toward which the gas underground may be traveling.

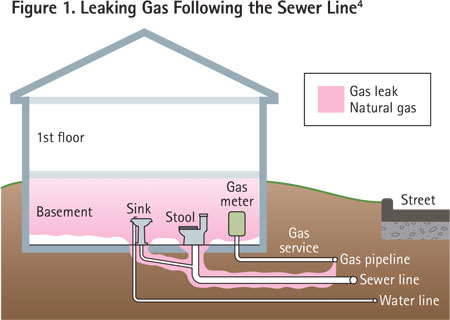

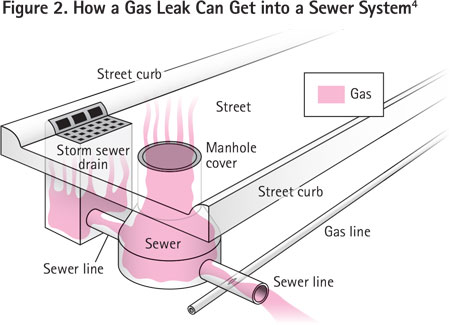

Figures 1 and 2 depict how leaking gas can enter and follow a sewer line.

Good sources of initial information to help you with your size-up follow:

Residents. They may be at their doors and windows trying to determine what is going on. Although we do not equate the human sense of smell with the accuracy of a gas detector reading, we know that humans can smell the odorant in natural gas at very low levels. Ask them if they smell gas inside their building. If they say yes, you may want to evacuate that home quickly or check it with an air monitor very soon. This information also gives you preliminary information about how far the gas has migrated.

If they say no, it is the best information you have to go on for the moment. You can come back and air monitor that building as soon as possible or concurrently assign incoming units to do it. If all you have is a short-staffed, first-due assignment, move on and work from the odor site outward. If you have more boots on the ground, assign them quickly. ( We discuss air-monitoring in greater detail later in this article and in our third article in the May issue.)

Subsurface structures (SSS). They are also reliable indicators of where underground gas may be migrating. Air monitor these SSS, which are underground spaces where gas can accumulate; these spaces include storm and sanitary sewers and phone, cable TV, or electric manholes. Obviously, they all may lead to nearby buildings and provide an excellent route for gas migration. Place your combustible gas indicator near openings in these structures and monitor the air for natural gas, or pull the cover if the space is not vented.

Any flammable gas readings in these SSS indicate that gas from the odor site is migrating into these spaces and could be entering nearby buildings. This possibility should increase your concern. Check inside the nearest buildings for gas with air-monitoring equipment, and evacuate as needed.

As in the case of the size-up of a fire, there are no black-and-white answers. You will, however, get clues that will help you put together a common operating picture of the leak scenario and gas-migration pattern.

Manhole covers (except storm drainage manholes) may have a second lining/cover under the cast-iron cover at street level. The lining is called an “inflow protector cover”; it can be made of plastic or metal and can easily be removed. The liner is there to keep water and debris out of the manhole.

|

| This gas leak is following the sewer line into the home, after leaking at the service tee. Natural gas can migrate in this manner. |

According to a manufacturer, the bottom edge seals with a gasket to prevent water infiltration, and a gas-relief valve in the center relieves pressure at one pound per square inch. Don’t depend on the gas-relief valve, however. It may be clogged with dirt, sand, ice, or debris or may not have enough gas pressure under it to force it open. To effectively air monitor manholes with inflow covers, remove the covers to get a good air sample. Limiting storm water intrusion, especially into sanitary systems, reduces the amount of water the waste water treatment plant has to process and is an environmental quality issue.3

If you find natural gas has migrated into SSS, open the SSS to provide a path of least resistance for escaping underground gas. This, of course, does not guarantee it will solve the problem of migrating gas into nearby buildings, but it is a good tactical option that does no harm. Of course, position a firefighter or several cones or other safety device around open manholes.

Often, gas will migrate up through the soil from the leaking pipe and be detectable at cracks in pavement, sidewalks, or porous soil. Place your air monitor close to the ground to get a reading. Another important fact to keep in mind is that the odorant in natural gas can be scrubbed out if the gas passes through the correct soil conditions. This is another reason not to trust your nose and to use your meter at gas emergencies.4

Utility. The third source of preliminary information is the utility, which, as mentioned in our March article, is required to maintain a list of existing leaks. Have your dispatcher call to ask if there is a leak at this site. You will still have to consider that this may be a new leak and run your procedures; but if you know where the existing leak is, it will improve your overall response. Additionally, you may find evidence in the form of bar holes, excavations recently repaired, or mark-outs indicating the utility had investigated the leak prior to your arrival this time.

If you keep your rigs outside the kill box and walk toward the area of the reported leak, quickly air monitor SSS on the way in. A word of caution: The area of your greatest concern for life safety must be closest to the location of the odor. Don’t excessively delay getting to that site. You may want to quickly or concurrently (if staffing allows) air monitor SSS as previously described to start to determine how far gas has migrated underground and to determine where the life hazard may exist.

|

| This is an example of how a gas leak can get into a sewer system. This is why it is essential when conducting a leakage survey to check all available openings, including manholes, sewers, vaults, etc. Consider any indication of gas in a confined space or in a building a hazardous situation. Remove persons from the area and eliminate ignition sources. Once this is done, the leak investigation should begin, and the leak, when found, should be repaired. Monitor the facilities affected and determine the gas migration pattern. Vent the gas from the soil and structure before allowing persons to return to the area. |

The Fire Department of New York (FDNY) training bulletin “Natural Gas Emergencies” recommends that fire department personnel open sewer manholes but not electric manholes. Open electric manholes only when utility personnel request it and the fire department incident commander (IC) approves the request.5

Stray voltage is a potential concern associated with fire department personnel opening electric manholes. Although it occurs infrequently, metal manhole parts can become energized with lethal amounts of current. Utility personnel should check for stray voltage before firefighters open these holes.

In cities and other areas where underground electric service is provided, electric conduits can provide a rapid channel for gas migration into nearby buildings. It is a good practice to check all buildings serviced by electric conduits in the underground gas migration pattern. Check with your local utility response procedures for complete details.

Tactical Considerations

During your next response to a call for an outside odor of gas, you can use the several tactical options that follow to execute the above strategic considerations.

Teamwork. The “one team, one fight” concept applies especially to underground gas leaks. The fire department brings multiple people to the call, which allows the team (gas technician and fire department) to conduct multiple operations at once. For example, the gas technician can evacuate only one house at a time; we can do multiple evacuations, shut off multiple meters, and so on. The gas technician, of course, brings expertise, the ability to shut off street valves, additional air monitors, and additional utility resources later in the incident if they are required. Every response that involves both the fire department and the utility must be a precoordinated, pretrained team effort. Imagine the chaos if engine and truck companies are not coordinated.

What will the first gas company response do to help you at this incident? FDNY Battalion Chief (Ret.) Frank Montagna says the initial utility response is typically one utility representative and that the representative and his tools and equipment likely will be all of the assistance the fire department can expect for a while. Montagna recommends that, since firefighters often will be on site before the technician, they should become knowledgeable about the potential hazards, the safety measures needed, and the appropriate actions to take and not to take.6

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto4.jpg" alt="(4) An underground gas leak migrated into a nearby house, causing a massive explosion that severely injured two firefighters. The explosion ignited the gas that was leaking through the pavement. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.)“> |

| (4) An underground gas leak migrated into a nearby house, causing a massive explosion that severely injured two firefighters. The explosion ignited the gas that was leaking through the pavement. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.) |

Of course, the utility worker has his own set of protocols to execute as mandated by his response procedures. Often, this results in an uncoordinated response, two teams without a single game plan. The utility representative does his procedures, and the fire department follows its protocol. Montagna says that shortly after the technician’s arrival, he should report to the fire department IC for a briefing on what transpired while the fire department was on site. The fire department should report the hazards its responders noticed and the actions they took or are contemplating taking.

After the utility representative’s size-up, ask what problems he discovered and what actions you can take to mitigate the danger. Of course, he may need to begin immediate mitigation if there is an imminent hazard he can address, but you need to talk to this person. It might be useful to assign a firefighter to him as a liaison to receive and relay critical information, discoveries, or requests for assistance. Assigning a fire department liaison to the gas technician solves two problems: The gas technician may be in basements, in or behind buildings, and not accessible to the fire department IC, and it provides instant radio communication and coordination from the gas technician to the IC.

As noted in our March article, joint training, a hands-on scenario-based training with your utility workers and firefighters, is a huge force multiplier that will vastly enhance your response effectiveness and safety. Consider also establishing a joint radio frequency between the gas technician and the fire department. Many departments cannot assign one of the few people they have responding to find, follow, and communicate with the gas technician. In discussion with firefighters across the nation, we have found most utilities are very cooperative, but some remain stubbornly opposed to meaningful joint training.

Bar holing. The gas technician usually brings a bar hole device. According to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), “A bar hole is a small-diameter hole made in the ground in the vicinity of gas piping to extract a sample of the ground atmosphere for leak analysis.” It helps him determine the extent of gas migration underground and near building foundations. Meter readings of gas in bar holes near buildings increase the importance of getting readings inside the home, especially in the basement, to sense for migrating gas. Life safety first, of course, is the mission here.

Bar holing near a foundation of a building may give you a clue about the possibility of gas entering that building and the extent of underground migration. A good practice is to check inside the foundation for migrating gas if there is a gas reading in a bar hole within five feet of the foundation. Consider also points of entry – penetrations in the foundation by gas, water, electric, and cable lines that may facilitate the migration of gas from an underground leak. Check with your local utility for its specific procedures and how to coordinate this critical information when the gas technician discovers it.

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto5.jpg" alt="(5) Air monitoring subsurface structures provides an indication of gas migration underground and through utility lines. (Photo by Jerry Knapp.) “> |

| (5) Air monitoring subsurface structures provides an indication of gas migration underground and through utility lines. (Photo by Jerry Knapp.) |

Many utilities have computerized their system engineering drawings, valve locations, and other critical information that can assist the IC. The gas technician may have a laptop computer in his truck that can instantly pull up this information.

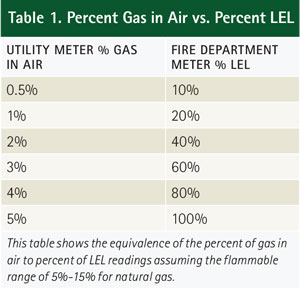

The technician can also bring disastrous confusion to the scene: He may report that he has eight-percent gas readings. Most fire department air-monitoring instruments measure percent of the lower explosive level (LEL). Therefore, eight-percent LEL is not a major concern to the fire department, but the technician likely is talking about eight percent of gas in air! The area with this reading is in the flammable range. The bottom line here is to ask the gas technician whether his reading signifies percent of gas or percent of LEL.

Just as water on the fire minimizes all other problems at a fire, so, too, shutting off gas meters helps minimize ignition sources (pilot lights) in buildings where gas has migrated and accumulated. Other ignition sources such as electronic ignition systems and other arc-producing devices still exist, but minimizing the possibility of disaster is always a good idea.

Art and science. Gas leaks and underground leaks are especially difficult to size up and mitigate. They necessitate a complex mix of your art of size-up, cooperating with the gas tech, applying your policy and procedures, and the science of using and interpreting meter results. Like our application of paramedic protocols, gas response procedures continue to evolve based on experience. The emphasis on life safety first by concentrating the initial effort on the buildings closest to the leak, as described above, is the result of experience.

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto6.jpg" alt="(6) Gas technicians and fire department personnel should have joint training and one common plan. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.)“> |

| (6) Gas technicians and fire department personnel should have joint training and one common plan. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.) |

A recent example of this was a house explosion in Floral Park, Queens, New York, on April 24, 2009, that claimed the life of a 40-year-old woman; caused several other civilian injuries, including the gas technician; and destroyed one home and severely damaged others.7

According to the New York State Department of Public Safety, the procedures in place at the time of the incident were adequate and contained the necessary information for the Con Edison first responder to react appropriately. However, the investigation showed that “he failed to follow certain provisions of the procedures critical to the protection of life and property.” As a result of this incident, Con Edison revised its procedures for identifying situations that require enhanced emergency response, getting more personnel on the scene quickly, venting SSS, and checking and evacuating nearby buildings if necessary.

Inside Odor of Gas

What is your first thought when toned out to this call? Stove left partially on, pilot light out. What is your department’s policy and procedure? You have two options:

- Evacuate the home, shut off the gas, and wait for the gas technician.

- Enter the home; air monitor and find and fix the leak; or shut off the appliance at the most local isolation valve, preserving gas service to the remainder of the home.

Our mission is life safety first, which would be option 1. This option may be the choice for suburban and rural departments with mostly single-family homes. Your department may choose to go beyond these actions and attempt to find the leak and isolate it until the gas technician arrives (option 2). This is the action usually taken by departments with a large number of apartment buildings in their response area.

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto7.jpg" alt="(7) Test for natural gas at exterior doors and windows. Any reading and level of gas present should require immediate tactical withdrawal. (Photo by Jerry Knapp.)“> |

| (7) Test for natural gas at exterior doors and windows. Any reading and level of gas present should require immediate tactical withdrawal. (Photo by Jerry Knapp.) |

The important point here is this: Your senior leaders need to set the policy for what you are expected to do on the scene and provide procedures, training, and equipment to execute whatever the choice is. The policy/procedure needs to be the same whether Lieutenant Smith or Lieutenant Jones is in charge. For example, if your firefighters are expected to track down an inside gas odor and shut the nearest valve to the appliance and preserve service to the remainder of the building or home, additional training on residential gas systems, detection equipment, and so on is required. We must remember that the 21-year-old firefighter who has no experience in utilities may not understand residential gas piping, valves, and equipment.

Usually, information from the homeowner provides the first clues: “I smell gas in the kitchen” We have all been to many of these incidents. A pilot light was out, causing the odor. You fix it. Or, it could be a cracked flex line, and you shut off the isolation valve.

But if you think life safety first for your members, another approach to the call is possible. Ask the complainant to come outside and describe the complaint. Fire up your air monitor (in clear air) and take a reading just inside the entrance. If it is safe, move in. If you think there is a possibility of an underground leak that has migrated to the house, check the basement, points of entry, and other utilities with a meter. Once you verify that dangerous quantities of gas are not below you, find and fix the problem according to your SOPs.

Action Level

If you are using an air monitor to get a numerical reading, your department should have an action level for mandatory evacuation of civilians and firefighters. Many utilities use 0.5 percent gas in air, which equates to 10 percent LEL on our meters for mandatory evacuation. Most meters are set to alarm (low) at 10 percent LEL. This should give you plenty of time and space to avoid dangerous situations. Does this mean you have to wait until you get to 10 percent LEL to evacuate? Of course not. But, it does mean that your members will get out of harm’s way at 10 percent or greater unless extenuating circumstances prevent it. Some departments set their action level at any odor of gas; others set it much higher, and others have it at 10 percent LEL. Choose your action level based on available resources, but make sure it is part of your policy and procedures.

Interpreting your meter readings is critical for success and safety at inside gas leaks. Fortunately, most of us have never seen our meter go into alarm at or above 100 percent LEL. What does your meter display when you exceed 100 percent LEL? Surprisingly, we have found a wide variety of nondescript displays on commonly used meters. One simply displays “OFF,” not to signify it is turned off but to indicate it is off scale. Does your young firefighter know that? Another meter displays “***.” This symbol doesn’t indicate anything unless you have read and remembered the instructions that came with the meter. Another model reads “OL,” indicating over limit. If your SOPs direct members to find the leak, your training must prepare them with the necessary information and procedures to execute this effectively and safely.

Consider the risk at gas leaks: You have no plan B, and your turnout gear is not rated for the overpressure of explosions, razor sharp glass, or large flying parts of buildings. Life safety first means we will risk firefighters’ lives significantly to save civilian lives. Life safety first also may mean not risking firefighters to find and fix a gas leak that can be resolved other ways. Let’s look at a scenario.

Scenario

Your department needs to answer the following questions when establishing policy and procedures:

- When civilian life safety has been resolved, what risk is acceptable to firefighters for the remainder of the call?

- Is it acceptable to risk firefighters to enter a building that contains no life hazard (until we enter) to reduce the hazard of trapped natural gas?

- What actions can be taken to reduce the hazard to members if the choice is to find and fix?

One universal safety consideration for gas emergencies is to reduce or eliminate ignition sources before risking firefighters. If both gas and electric services had been shut off before these firefighters entered the building, the environment may be safer to work in.

Shutting off the gas at the building meter will reduce ignition sources of pilot lights. Since the pilot light consumes only a small amount of gas, it may take some time to bleed down the gas line supplying it. Many gas-fired hot water heaters, hot air furnaces, or boilers have electronic ignition systems with a spark generator instead of a pilot flame.

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto8.jpg" alt="(8) The gas technician, 45 minutes into the alarm, asked the fire department to force the door to gain access. Two firefighters near the building were nearly killed when it exploded. (Photo by Tom Bierds.)“> |

| (8) The gas technician, 45 minutes into the alarm, asked the fire department to force the door to gain access. Two firefighters near the building were nearly killed when it exploded. (Photo by Tom Bierds.) |

Shutting off the electric service from a safe location is another option. Utility companies can shut off service from an overhead or underground service a safe distance from the scene. This action often takes considerable time: You need utility assistance to remotely shut off service to multiple customers, and it takes time for a crew with the proper equipment to arrive and accomplish it.

Montagna cautions that shutting off electric is not a conclusive exclusion of ignition sources. Removing power, he explains, can be the source of ignition. He cites as examples emergency generators and emergency lights. Even the act of removing a meter can be an ignition source when it creates a spark. Any time a switch is opened or closed or electrical connections are parted, there likely will be a spark, which could be a source of ignition. Remove power only if you can do it safely.

Locked Building

If you are operating at a gas leak scenario and you think that gas has migrated into a nearby building, you are dealing with a potential big bomb with a big kill box. How do you know that this locked building has gas in it? Use your meters from outside at windows, doors, or other penetrations in the building. Taking the readings exposes firefighters to a degree of danger, but it also will help you to determine how far gas has migrated, how big your kill box should be, and how far to evacuate firefighters and civilians.

The most important fact about this scenario is that there is no safe way to vent the flammable mixture. If you assume a locked single-family home or row house contains gas from an underground or internal gas leak source, how could you safely ventilate the building and mitigate it? If you force the front door, there is a chance that sparks from the tools or hitting a nail during the forcible entry process or another ignition source (boiler, hot water heater, for example) will ignite it while firefighters are operating. If you decide to take a 24-foot ladder and drop it through a window, you endanger your members. You cannot use an aerial ladder because you are too close to the building. If you send a firefighter with a long hook to break a window, he would be in an unpredictably dangerous situation. If that same firefighter climbs through the window, he is now inside the potential bomb. If you throw a rock through a window, you create only a small vent hole. If you vent the building before you eliminate the flammable mixture and ignition sources, you take an unknown amount of risk. Taking risks with locked buildings containing gas is akin to playing Russian roulette: You do not know when or if this building will explode, and there is no Plan B for the safety of your members.

| <img src="/content/dam/fe/print-articles/2017/04/1704FE_KnappPhoto9.jpg" alt="(9) Immediate postblast: Search, rescue, and fire suppression are priorities, as is determining if gas migrated into other nearby buildings. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.)“> |

| (9) Immediate postblast: Search, rescue, and fire suppression are priorities, as is determining if gas migrated into other nearby buildings. (Photo by Dominick D’Alisera.) |

Some utilities request the fire department to force entry into locked buildings that may contain fugitive gas. Other utilities strictly prohibit this procedure. It appears that the best course of action, which is contained in some good SOPs, is to first eliminate ignition sources – shut off the electric service to the building from a safe location and shut off the gas; let the building vent on its own. This should be a decision made at the fire department command post and should be based on joint scenario-based training.

If you are presented with a life-safety-first issue at a locked building, what can you do? First, determine the reliability of the report that someone is inside. Of course, getting the utility to shut down electric and gas service to the building would greatly increase safety. Before risking firefighters’ lives, ask neighbors if they know, and how they know, if occupants are home. Alternatively, depending on the threat you perceive and the level of your staffing, use loud speakers, sirens, and air horns from your rig to initiate a self-evacuation. If there is an urgency to conduct a search operation, take a window instead of a door. This will not cause sparks or provide an ignition source.

At a locked building scenario, ask yourself these questions: “Do we have to get in that IEB right now, or can we shut off ignition sources and wait for the building to vent down naturally?” “Should the fire department or gas technician take readings from outside the windows and doors during this time?”

Explosion

Unfortunately, often our first indication of a gas leak is a building explosion. As has often happened, that explosion can be the prelude to additional area explosions that injure firefighters. Secondary explosions have killed firefighters and destroyed additional houses as firefighters operated to rescue trapped occupants in the first explosion. We normally conduct investigations into the cause of a fire after the fire has been extinguished. In the case of a gas explosion, we need to determine the cause during the response to protect ourselves from further danger (exploding buildings).

Obviously, your goal at a gas explosion is twofold. First, conduct search and rescue operations and extinguish or control exposure fires. Simultaneously, you must quickly determine if this is an isolated gas leak or whether gas is migrating into nearby buildings and additional explosions are likely. This is a difficult and challenging task under extreme conditions, especially early in the incident.Another concern postblast is what secondary damage the original explosion caused. Are overhead/underground electric lines compromised? Is there a need for a technical rescue team to search the damaged buildings? Is there a collapse potential in the involved structure or nearby? Are there still leaking or burning gas-fed fires? Is the police officer who responded before you injured, dead, or trapped? Are bystanders or construction workers trapped, injured, or in danger?

If you apply the previously mentioned procedures/considerations to determine the source of gas emergencies, it will help you develop your postblast response strategy. Close coordination with the utility is also crucial; finding and shutting off gas valves and electric service to the area in question are key components to success.

Leak with Fire

This is another scenario in which we may let our guard down. We think, “the gas is burning; we have no other worries.” This may be true; however, we must remain fixed on our priority of life safety first. The flame shooting up from the trench and the burning backhoe get our attention. It is important to check surrounding buildings for migration of gas and determine if the burning gas is your only concern.

Obviously, radiant heat may be a huge problem when exposures are being threatened or burning. Water on exposures is the best way to protect them because water curtains are not dense enough to absorb the radiant energy. In a 13-alarm fire in the Jamaica section of Queens, New York, to which the FDNY responded in 1967, a gas main sent a 20-foot-wide column of flame 150 feet above the street. Five buildings were destroyed and 15 others were damaged. Hundreds of sleeping residents had to be awakened and evacuated as a major “life safety first” task. The fire department also had to deliver huge amounts of water to protect exposures and fight fire.8

This article has highlighted some of the strategic and tactical considerations necessary for safely and efficiently responding to incidents involving natural gas leaks. Following gas industry best practices and your procedure-based protocols combined with good size-up and air-monitoring skills will help you to successfully mitigate natural gas emergencies.

Authors’ note: Thanks to Chief James Comstock of the Henrietta (NY) Fire Department and Cynthia McCarran of the New York Department of Public Service for their contributions to this article.

Endnotes

1. Democrat & Chronicle, www.democratandchronicle.com/picture-gallery/news/2016/02/02/home.

2. “Blast Rocks Aerial Platform,” Donald B. Coasts, Fire Engineering, Dec. 1970, 31.

3. USABluebook.com, catalog for waste water professionals, 259.

4. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, Chapter 4, “Leak Detection,” 49CFR, 192.

5. “TB Emergencies #2 Natural Gas Emergencies and Fires,” Fire Department of New York, Dec. 2008.

6. “Utility Response: What You Can Expect and What You Should Expect,” Frank Montagna, Fire Engineering, May 2015, 55.

7. The Safety Section of the NYS Department of Public Service report (See case # 09-G-0380 on the DPS website), Nov. 2009.

8. “New York’s 13-Alarm Night of Flame,” Dick Sylvia, Fire Engineering, April 1967, 45.

JERRY KNAPP is a 40-year firefighter/EMT with the West Haverstraw (NY) Fire Department and a training officer with the Rockland County Fire Training Center in Pomona, New York. He is chief of the hazmat team and a technical panel member for the Underwriters Laboratories research on interior and exterior fire attack at residential fires. He is the author of the Fire Attack chapter in Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II and has written numerous articles for Fire Engineering.

DANIEL MORAN is a 45-year fire service veteran; a Rockland County (NY) deputy fire coordinator for hazardous materials; a member of the Rockland County (NY) Hazardous Materials Team; an instructor at the Rockland County (NY) Fire Training Center; and a former chief of the Suffern (NY) Fire Department. He has more than 40 years in the chemical-pharmaceutical industry as a research chemist. He has a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Lebanon Valley College, Annville, Pennsylvania, and a master’s degree in chemistry from Fairleigh Dickinson University, Teaneck, New Jersey. He is an adjunct faculty member in the fire technology program of Rockland Community College in Suffern.

Strategic Plan for an Underground Gas Leak

Jerry Knapp will present “Tactical Response to Natural Gas Leaks” at FDIC International in Indianapolis on Wednesday, April 26, 2017, 1:30 pm-3:15 pm.

Improving Response Procedures to Natural Gas Emergencies

NATURAL GAS EMERGENCIES

Natural Gas: Safe, Reliable, and Potentially Deadly

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles

Fire Engineering Archives