BY MARK W. HERENDEEN AND BRIAN WARD

Currently in the fire service, multiple generations are playing active roles in the everyday operations, including the veterans, the traditionalists, Generation X, Generation Y, and the millennials. These individuals may be firefighters, company officers, chiefs, and trustees/board members. Most of them, regardless of their current position, came up through the ranks, learning the task at hand and working to increase their knowledge every day. The veterans and Baby Boomers must pass down the knowledge and the skills they received over their careers from their generation to the current ground troops so the new generation knows the historical perspective of where we have been and where they are going. Below we discuss generational differences and how mentoring impacts the overall health of the organization. We also examine the Rocking Chair Firefighter, the Tough Guy/Gal, and Green Ears from a generational perspective and share a few tips from our experiences on how to blend these generations.

Behavioral Modeling

In Barn Boss Leadership, I (Brian Ward) describe applying behavior modification from my experiences as a young, late Gen Xer as a driver/engineer with Gwinnett County (GA) Fire and Emergency Services. When you understand how your influence affects those around you (regardless of the generation), you will understand how important you are to the core of your crew.

One example of this was when I worked as a driver/engineer at Station 4, a “double house” (truck and engine company). At the same time, I had been accepted into the Georgia Smoke Diver Program and was competing in the Scott Firefighter Combat Challenges. My cohort (retired Ironman and early Gen Xer) Driver/Engineer Alan Hurd and I would set up obstacle courses with fire department equipment, gear up, and drill as a daily routine. Without threats, intimidation, or demands, we conveyed our expectations; the crew understood where the bar was set. In Station 4, the generational age difference spanned more than 25 years. The crew put themselves through brutal one- and two-hour training sessions perceiving this not as training but as reality. Now, it was not all physical labor; we had to be strong in mind, too; so we exercised our minds every day. We wanted to never let one of our team members down, so we trained until we could not get it wrong – this was our common vision. This station vision allowed us to put any differences aside and focus on organizational (station) alignment. We understood the “Team above I” concept.

|

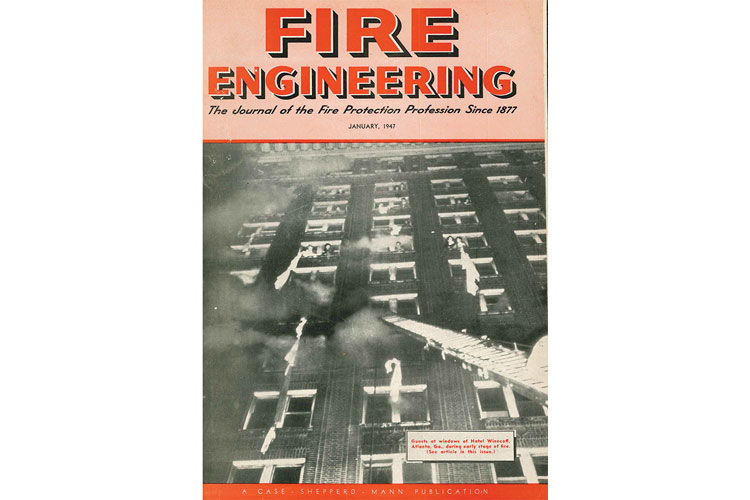

| (1) Photos courtesy of Fire Engineering. |

A recent study by Drexel University discusses firefighter safety as its focal point; however, one underlying theme was that veteran firefighters are the “influencers” in the station. We do not think this is anything new, since the veterans should be the influencers and running the station. However, some interviewees expressed concern about less experienced firefighters exhibiting unsafe acts on the fireground and from whom they had learned the unsafe behavior. The study’s conclusion focused on the public perception of risk taking and on following the veterans’ actions, even if unsafe. Is the newer generation of firefighters watching the veterans more closely than we may think? This could be positive, since we generally stereotype the newer generation as unwilling to work or take advice from veterans. Reviewing the behavior modifications I observed at Station 4, I realized that the younger and the older generations were paying attention to a couple of motivated Gen Xers. Alan and I bridged the generational gaps through leading by example.

Changing Behavior at Your Station

- Use some introspection and correct your behaviors first; then set the bar and lead by example. Be careful in thinking it is everyone else who has the problem.

- Provide opportunities for all the generations to get involved together, work together, and struggle together. We can learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses and, thereby, become stronger as a team. It can be as simple as allowing less experienced firefighters on the research and development committees or to lead such projects as testing new turnout gear. One local combination department assigned a firefighter to lead the project on creating gear specifications for its new turnouts. If you want buy-in, this is how you get it.

- Learn the behaviors and interests of your team members. A kitchen table talk allowed me (Ward) to learn that my six-month rookie was a licensed electrician long before I received the call to respond to my first industrial man-vs.-machine incident. Who better to have on such a call than an electrician, and who cares if he is a rookie firefighter on this specific incident? The value of learning little nuggets of information such as this can save time and lives during an incident.

- Provide constructive feedback on the tailboard before you leave the scene. The response is fresh on everyone’s mind; and from a learning standpoint, this is the perfect time to lock the knowledge in. No textbook or PowerPoint® will ever compare with an informal class at the incident scene. This is mentoring – learning the job above you and teaching your job to those below you.

Blending Generations

Earlier we mentioned the Rocking Chair Firefighter, the Tough Guy, and Green Ears. Although each one may have knowledge and skills to offer each other, it will be detrimental to the crew if they do not have a common ground. Establishing a vision for your crew, as was done at Station 4, will align your organization’s members regardless of their differences.

During a recent interview with Shift Supervisor Gary Thigpen, Columbia County (GA) Fire Rescue, we discussed the difficulty of being young up-and-coming officers and facing employees who have double our years of experience. The key for us was to listen to veteran employees and ask for their input. In my (Ward’s) situation, the department had gone through five leaders in three years; there was no trust, consistency, or sustainability of leadership. During one of my first department meetings, one well-respected and outspoken veteran asked in front of the entire crew, “Why should we trust you?”

What do you say? I didn’t say much. I let my actions over the next few weeks and months speak for me. They needed to know they could trust me. Two years later, I promoted this employee because he was one of the best in the organization. Despite the 25-year life experience gap between us, we did not let this difference impede our vision for a better department. Looking at the firefighter types below, consider what makes them tick, what their motivation is, and how you can bridge the generational differences.

The Rocking Chair Firefighter

This firefighter has experienced it all and is just waiting for the next alarm. “We get paid the same whether we run a fire or not.” In our younger years, this thinking was completely unacceptable. As we got older, this thought process became acceptable between 2200 and 0600 hours. Training is not required for these individuals, or so they “think.” They have seen it all and have a “been there, done that” mentality. In some cases, they have a tremendous wealth of knowledge and skills but are not sharing it.

If you’re the 30-year veteran, pass along your knowledge and skills. Provide the less experienced firefighters with the historical perspectives of why things work the way they do. This will impact the next generation and how they respond to the generation after them.

Green Ears should be in this Rocking Chair Firefighter’s back pocket, soaking up as much knowledge and information as possible. He should annoy this veteran by asking a thousand questions.

Historical incidents to explore include the following:

- The 1946 Winecoff Hotel fire (Atlanta, Georgia), the deadliest hotel fire in America, killed 119 people. This incident is directly related to the development of National Fire Protection Association 101, Life Safety Code, and is described in Fire Engineering (photo 1).

- The 1988 Hackensack, New Jersey, Ford fire, which focused national attention on bowstring trusses after five firefighters gave their lives inside of an automobile dealership that featured bowstring trusses (photo 2).

- The 1937 deadly school explosion in New London, Texas, after which state legislatures mandated adding mercaptan (that rotten egg smell) to natural gas. The disaster killed 294 children and teachers.

- After the 1999 Cherry Road, Washington, DC, incident, the National Institute of Standards and Technology conducted the first studies on flow paths after two firefighters perished performing as they were trained to do. Flow path terminology did not become mainstream until 15 years later.

The Tough Guy/Gal

The Tough Guy/Gal mentality develops somewhere around the mid-career point. You’ve put a few years in the department, have seen some fires, have been successful to some degree, and start to feel good about the job. This individual is looked up to by many of the newer generation. Because this person is a bridge between multiple generations, he becomes a prominent figure. However, if such individuals do not humble themselves, they will tear a crew to pieces. The cockiness, the attitude, and the bully mentality will completely destroy morale and alienate the generations even more. The Tough Guy/Gal needs to learn his strengths/weaknesses, leverage his strengths, and be aggressive but smart in everything. For his weaknesses, he should say he does not know and seek the necessary knowledge. As the Tough Guy/Gal builds up his weak areas, he should bring Green Ears along and ask the Rocking Chair Firefighter to share his experiences. As a mid-career person, you can be the most influential individual in the station and bridge every generation by tying together the veteran’s trial-and-error experience with the millennials’ knowledge of science and technology.

Green Ears

This individual may be a rookie with the department or a newly promoted officer. Regardless of your title, you are green to the position. Find mentors who can assist you in developing your career each step of the way; don’t wait for them to seek you out. Listen first, be respectful, be humble, and show appreciation for what others are teaching you. Ask the Rocking Chair Firefighter and the Tough Guy/Gal for their guidance and input (it works as a rookie and a new officer). Considering the various generations, look for opportunities to bring everyone together for training or maybe just a kitchen table talk – you’re building relationships. Building these relationships is the most important component in bridging the generational gaps.

Working Together

As you work through the various stages of your career – rookie, mid-career, and veteran – never forget the principles of being a leader (formal or informal). If the Rocking Chair Firefighter, the Tough Guy/Gal, and Green Ears learn to work together, they will develop an unstoppable team. They will tear down all generational barriers through leading by example and not through influencing with threats, intimidation, or demands. It takes one individual to step up and start this process. It takes someone who cares and wants mastery as the minimum standard (be the Barn Boss).

Motivation is contagious, regardless of who you are. It does not require trumpets or 30 years to make this stand. The knowledge and experience from the Rocking Chair Firefighter, the aggressiveness of the Tough Guy/Gal, and the eagerness of Green Ears will make quite the team, and we will take any one of them every day.

References

Ward, Brian J. (2016). Barn Boss Leadership. Charleston, SC. FireServiceSLT.

Ward, Brian J. (2016, January). “Bridging the Gap.” Fire Rescue. Retrieved from http://www.firerescuemagazine.com/articles/print/volume-11/issue-1/command-and-leadership/bridging-the-gap.html.

MARK W. HERENDEEN is a 38-year veteran of the fire service and chief of the Madison Township (OH) Fire Department. He also served as chief of the Morrow (GA) Fire Department. Herendeen was vice president of the Metro Atlanta Fire Chief’s Association and is certified in Ohio and in Georgia as a firefighter II/emergency medical technician. He has a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in business administration. He has been a certified Chief Fire Officer since 2008.

BRIAN WARD is the chief of emergency operations for Georgia Pacific. He is an FDIC International instructor and is the author of Training Officer’s Toolbox and Barn Boss Leadership (Fire Engineering). A certified Georgia Smoke Diver, Ward is working toward a master’s degree in organizational leadership at Columbia Southern University.

Developing Leaders for the Next Generation

Bridging the Gaps Among the Generations

THIS YOUNGER GENERATION JUST DOESN’T LISTEN!

Fire Engineering Archives