BY SEAN GRAY

In “Attacking from the Burned Side Can Save Lives” (Fire Engineering, November 2011), I briefly mentioned the line-of-duty deaths (LODDs) and near misses associated with fires that burned on the exterior and into the attic space, causing a flashover. These fires can be extremely dangerous because the true conditions are hidden in the attic space and firefighters are not expecting the sudden change of conditions when the flashover occurs. Although the fires originate on the exterior, the action killing and injuring firefighters around the country is the flashover in the attic.

Many times during size-up, the smoke conditions and location will confirm an attic fire. The next questions you should ask yourself follow:

- 1. How did the fire get into the attic space?

- 2. Can I safely extinguish it?

- 3. Where should the initial hoseline be placed?

Safety is our top priority, and over the past few years, the LODD numbers have dropped by 15 percent from the average of 100 that had become our norm. That’s great news, but we can improve those numbers if we educate ourselves about this type of incident.

We are still relying on old-school tactics to extinguish new-school fires. Many of the firefighters involved are unknowingly standing under a flashover when it occurs. Go back and read the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health reports on this type of fire. A common occurrence noted is “little or no smoke found on the interior of the structure.” Many also describe a sudden blast of heat onto the firefighters on the top floor.

LODDs AND NEAR-MISS INCIDENTS FROM ATTIC FIRES

Following are incidents in which an LODD or a near miss occurred in this type of fire:

- LODD. Chicago (IL) Fire Department-Captain Herbert Johnson.

- LODD. Prince William County (VA) Fire Department-Firefighter Kyle Wilson.

- Near Miss. Cherokee County Fire Department, Woodstock, GA.

- Near Miss. Fayette County Fire Department, Fayetteville, GA.

- Near Miss. Mehlville Fire Protection District, Sappington, MO.

- Near Miss. Minneapolis (MN) Fire Department.

- Near Miss. New Orleans Fire Department, Lakeview, LA.

- Near Miss. Richmond (VA) Fire Department.

- Near Miss. Pittsburgh (PA) Fire Department.

- Near Miss. New Chicago and Hartford Fire Departments, New Chicago, IN.

As you can see, there are plenty of recent incidents in the past five years that have injured or killed firefighters. The information below is a review of my personal experience with the “hidden blast.”

The photos are from a fire in which I was the officer on the first-due engine. We arrived just a few seconds ahead of the second-due engine. I established command and got a view of all four sides of the structure. We had heavy fire on a rear deck (photo 1) and moderate smoke conditions pushing from the eaves on all four sides. The initial hoseline was a 2½-inch preconnect to extinguish the C side deck fire that was extending into the attic space through the soffit vent and inside a 2 × 6 void space that was over a vaulted ceiling-living room (photo 3). A 1¾-inch preconnect was deployed simultaneously by the second-due engine crew through the A side front door to the second floor to extinguish the remainder of fire in the attic.

|

| (1) Side C, near the B/C corner. (Photos by author.) |

|

| (2) A/B corner. |

|

|

| (3) The 2 × 6 void space from soffit vent to attic. (4) A side. |

As the fire on the deck was quickly knocked down, we moved to the A side to assist with the interior attack. Very little smoke was seen inside the structure, and the conditions appeared to be safe. While we managed the hoseline on the front porch for the interior crew, a sudden whoosh of air occurred, and we felt a pressurized blast of air shoot out of the structure. I looked up and saw flames momentarily being pushed out of the eaves. Some type of explosion had occurred. As all of us checked ourselves and the battalion chief called for an immediate personnel accountability report, the smoke conditions in the eaves returned to a moderate state. We then proceeded upstairs to extinguish the fire in the attic.

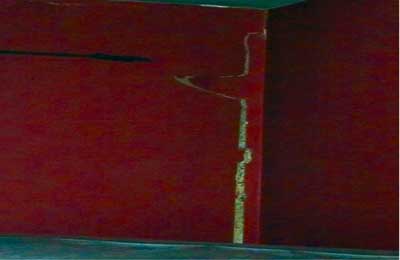

During salvage operations, we found interior and exterior walls that had been blown out approximately six inches (photos 5-6). The interior walls on the upper floor had very little fire/smoke damage. Most of the damage was contained to the attic.

|

|

| (5) Drywall damage in the upper-floor bedroom. Note that very little smoke damage occurred. (6) Exterior wall damage occurred between the windows approximately five feet below the peak of the roof (middle of the photo). |

Although our event was not significant enough to cause a collapse of the ceiling and there weren’t any injuries, it definitely got our attention. This could have easily been another near miss or LODD.

We attacked the base of the fire quickly, but it still did not prevent the attic flashover. However, by extinguishing the base of the fire first, we may have prevented a flashover of greater intensity.

After this fire, I was intrigued and wanted to learn more, so I contacted Stephen Kerber from Underwriters Laboratories (UL). After providing him with the details, he concluded that the event was likely a flashover with a pressure wave. That would explain the explosion-like event that occurred. He became interested in researching this specific type of fire and has recently procured funding for a grant to study exterior fires that extend into the attic space. The goal is to determine if there is a way to prevent these flashovers.

After this fire, I researched the number of fires that originated on the exterior of buildings in Cobb County, Georgia. I was shocked at the results. From 2003 to 2011, there were 8,699 fires in Cobb County that originated on the exterior of a structure and caused property damage. The fire origins varied from deck fires, brush fires, and car fires to smoldering ashtrays.

The large number of fires is of concern because it shows an increasing pattern for this type of fire. The fire service has been dealing with attic fires for many years, and multiple tactics from around the country have been presented at the Fire Department Instructors Conference and in firefighting publications.

TACTICS

Among the tactics you must remember are the following:

• Wear your personal protective equipment (PPE). It may be difficult to convince inexperienced firefighters to wear their full PPE because there will probably be very little smoke or fire visible on the interior of the structure. Complacency kills. These fires are hidden and waiting to flash over. Don your hood and mask before you enter the structure.

• Have a charged hoseline in place. This is a must before pulling ceiling. The UL ventilation study has shown that as soon as you pull the ceiling, you are giving the fire air and providing a flow path. It’s similar to opening the damper on a wood-burning stove. Chances are that smoke and fire will present themselves from the hole you make.

• Check the ceiling as you enter. As you do in a commercial strip mall fire, always check the space above you as you enter. This may be possible only at the top of the stairs in an open-foyer style home. Make a small inspection hole in the ceiling, and then move forward toward the suspected seat of the fire. Like in roof ventilation tactics, if something goes wrong, you will have a hoseline in place to extinguish or to assist in exiting the structure.

Modern construction has changed the game. The ever-increasing void spaces and the flammable materials used for exterior siding increase the possibilities for these hidden blasts. Also, fire can be hidden behind knee walls in a finished attic; this is common in older homes, especially in the Midwest and the Northeast. As part of the UL technical panel for the upcoming “Study of Residential Attic Fire Mitigation Tactics and Exterior Fire Spread Hazards on Fire Fighter Safety,” I hope that, as a group, we can solve what’s behind the hidden blast.

SEAN GRAY is a 20-year veteran of and a fire engineer with Cobb County (GA) Fire and Emergency Services. He has an associate degree and is working toward a bachelor’s degree in fire safety engineering through the University of Cincinnati. He has taught at FDIC and has been published in Fire Engineering.

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles

Fire Engineering Archives