BY DAN SHERIDAN

Fires in healthcare facilities are among the most challenging operations for firefighters. The major problem is the need to move a large number of nonambulatory patients in a short time while simultaneously dealing with a major fire. In these cases, we need to be proactive by getting lots of help on scene as soon as possible, even if it means transmitting multiple alarms before we arrive on scene. Remember, we can always send units back to the station if they are not needed.In 2009, the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) redesigned its “call taking” element for dispatching FDNY fire trucks. The new system has a Unified Call Taker (UCT 911), which works under the premise that when a caller wants to report a fire or an emergency he will only have to speak with one call taker. Once the UCT 911 operator enters the information, it is then routed to the FDNY dispatcher by computer link. The FDNY dispatcher then reviews the information and determines the appropriate assignment. While FDNY units are responding to the emergency, as more information becomes available the UCT 911 operator will route the information to the FDNY dispatcher to be relayed to the responding units.

Along with the new UCT 911 system, the department has also initiated a new Modified Response Policy to deal with the many nonemergency alarms it receives daily to help reduce the number of accidents. The idea is that the first-due engine and ladder respond in emergency mode and the remainder of the units respond in a nonemergency mode. A few examples of calls in the nonemergency mode would be odors other than smoke, electrical emergencies, and sprinkler alarm activations.

ALARM VERIFICATION

On a recent day tour, we received such an alarm from the Bronx dispatcher. The alarm ticket stated that it was a UCT 911 call for a nonstructural smoke condition in the street; however, to add to the ambiguity of the call, it stated “Fire” at the end of the dispatch ticket. We had just started with the Modified Response Policy in the Bronx, so there seemed to be some confusion. I had the units respond in emergency mode because of the information on the ticket: Fire. En route to the alarm box, we received additional information from the dispatcher stating that emergency medical services (EMS) was reporting that smoke was in the emergency room of the hospital at the location.

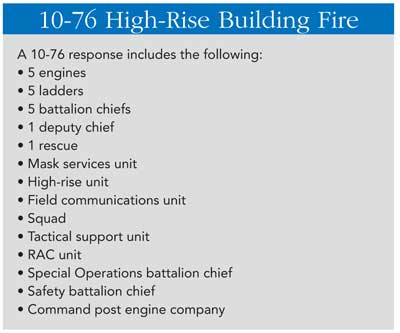

For a battalion chief, the most important component early in a response is information. Most times when I respond, I will get an address of the building; if I am lucky, I will get some preincident planning from the department’s Critical Information Dispatch System (CIDS) (photo 1). Armed with this information, I can start forming a plan in my mind for different scenarios. Having been assigned to the Bronx for most of my career, I am fortunate in that I know most of the buildings in my response area. Very rarely am I surprised. At this particular box for the hospital, the only information I had was that we had some possible smoke in the emergency room. I was not prepared for what lay ahead. When the first-due units arrived on scene, they advised the remainder of the assignment to respond to the front of the hospital, but they gave me no indication of what they had. When I arrived on the scene, it became pretty clear that we had a serious situation at hand when I saw that the police had blocked off the street.

|

| (1) A Critical Information Dispatch System card. This system allows the fire department to send responding units up to 160 characters of critical information, such as lightweight construction, major alterations, and hazardous materials. (Photos by author.) |

FIRE No. 1

When we turned the corner onto the main street in front of the hospital, I saw a heavy smoke condition in the street and hundreds of people in the street and on sidewalks around the hospital. I transmitted the signal for a working fire, even though I wasn’t sure what exactly was happening. I advised dispatch exactly what we had: heavy smoke issuing from a setback in the hospital and that I was going to use “All Hands” on arrival (photo 2). Having not received the Class 3 alarm, an internal fire alarm system, from the hospital and only a vague phone alarm reporting smoke, I wasn’t mentally prepared for what we were dealing with.

|

| (2) A one-story brick addition with the white stripe. The stack outside the hospital was pumping heavy black smoke into the street when fire department units arrived on scene. (Normally it is used to vent the steam generated from the three large co-generators in the basement.) |

I rely heavily on my units to give me good information. One firefighter report I received said it was just a rubbish fire in the shaft. I don’t know why, but I discounted that report and continued to look for the seat of the fire. I was able to track down one of the building engineers and received some very good information. He updated me on the following conditions:

- An emergency generator was on fire in the basement.

- The generator was fed by both natural gas and diesel fuel. Both fuel supplies had been shut down.

- Maintenance workers had stretched a house foam line.

- The hospital’s fixed (3 percent aqueous film-forming foam) piped system had been activated.

- The fire was confined to the one room.

- Five off-duty firefighters visiting a member from their company in that hospital took over the foam line and made sure that everyone from the maintenance crew was accounted for.

- The hospital staff had initiated the Internal Disaster Plan and were in the process of evacuating patients.

I was starting to get a clearer picture of what we had-a serious fire in the generator room with a heavy smoke condition in a fully occupied hospital. The building is 11 stories high and takes up a whole city block. The areas most affected were the basement and the first floor with 8,000 people on it. I can’t think of many “worst-case scenarios.” The smoke was venting straight up the stack (photo 3), but I was receiving reports that some smoke was entering the emergency room and the critical care areas on the first floor. With the hospital’s evacuation plan in place, I felt that we were in good shape, but the trigger point in the operation that prompted the second alarm was when I overheard the first-due truck officer call for a search line because of the heavy smoke condition in the basement. We now had to deal with evacuating the 165 occupants from the emergency rooms and the intensive care units-a monumental task. I knew that the fire was being controlled by the sprinkler system and the house line, but we still had to deal with the evacuation.

|

| (3) An inside view of the stack used for ventilation. The stack greatly assisted in keeping most of the smoke from entering the main hospital. |

Besides dealing with the numerous bedridden patients, which is very labor intensive, we also needed to address the perception of the situation. The problem isn’t the reality of the situation but rather how it is perceived by the hospital occupants. Civilians don’t know anything but that they are in a fire and need to get out. Firefighters see it many times in their careers-for example, a one-room bedroom fire in a multiple dwelling with a decent smoke condition and no extension. The civilian just knows that there is a fire and that means get out. We now live in a post-9/11 world where many civilians witnessed the collapse of the World Trade Center towers.

My attention was then turned to the engine companies. They were in the process of stretching a hoseline. I heard the first-due engine officer call for a hoseline. I interjected between their transmissions and ordered them to stretch a foam line based on the fact that it was a generator fire. Herein lies the dilemma: To fight the fire, we needed to open the door to the subbasement to get the line in place and the foam on the fire (photos 4-5). The generator fire was caused by a glass tube that had cracked and resulted in diesel fuel spilling out onto the hot generator. The fuel then ignited, causing a very heavy smoke condition. The fuel kept leaking out and eventually covered most of the floor surrounding the generator. At this point, the sprinkler system activated and extinguished the immediate fire, but we still had fuel flowing that was on fire. The hospital’s heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system shut down when the sprinklers activated, but the smoke still found its way into the hospital’s interior.

|

| (4) Outside the fire area. Note that the hose was rolled around the wheel the day of the fire and has since been changed. It caused a delay because the whole reel had to be deployed. The dilemma was that with the door open to attack the fire, the smoke contaminated the hospital. |

|

| (5) The dilemma: This photo was taken in front of an elevator shaft. To attack the fire, we needed to open the door (next to the rolled hose on the reel). Those hallways lead to numerous shafts that allowed smoke to enter the hospital. Luckily, the vent opening inside the generator room removed most of the smoke (see photo 3). |

At this point in the operation, we had hospital staff dealing with the evacuation while the fire department took over the extinguishing duties. The hospital staff did a tremendous job and evacuated everyone needing to be evacuated from the emergency room and intensive care areas in about five minutes. The fire was basically extinguished in about four minutes. This is a testimony to the training and professionalism exhibited by both parties. The fact that we evacuated 165 patients in five minutes without a single injury is incredible. Some of these patients were on life support and needed to have a battery supply power to their life-support machines.

I have been to four healthcare facility fires, three of which were hospital fires and one a nursing home fire. Every time we get a call to a hospital, I always think the best: It is probably some defective alarm or a patient sneaked a cigarette in his room and set off the smoke alarm. We think of hospitals as safe places, but this may not always be the case. On December 9, 2011, 94 patients were killed in a hospital in Kolkata, India. Many of those killed were bedridden.

HOSPITAL FATAL FIRE

As we move up the ranks in the fire department, the way we see things and our responsibilities changes. The way we saw things as responding firefighters is totally different from the way we see them as a chief.

My first hospital fire was about 20 years ago. I was working in the squad. Our assignment was first-due engine. I really don’t remember much about the fire. I remember a patient on oxygen was smoking, and the room lit up. She was fatally injured, and there wasn’t much left of the room. I do remember being in a heavy smoke condition. There were fire doors on the floor, and we could see hospital staff working as if nothing was going on.

The impression I walked away with from that experience is that everything doesn’t stop because there is a fire. The priority at that incident was to keep the operating rooms functioning and to do the best to defend in place. The hospital is a place where life-and-death operations are happening around the clock. Moving patients is done only when absolutely necessary.

THE NURSING HOME ARSON

One lesson I took away from the following incident was to never assume anything. We had responded numerous times to a nursing home in the North Bronx for alarm activations that most times were unfounded. Maybe there was an occasional food-on-the-stove fire.

I was still a lieutenant when we had this fire on the top floor of a nursing home. When we arrived, there was no indication that anything unusual was going on in the building. I was working in the ladder company that day; our assignment was to locate the fire. The ladder company’s duties are like those of a recon unit, whose function is to locate; confine; and, if at all possible, extinguish the fire if it is minor.

When we got to the fire floor, we encountered heavy smoke. Someone had ignited a bunch of beds. Thankfully, the sprinklers had extinguished the fire and the patients had already been evacuated. We vented the top floor, performed a primary search, and overhauled. This could have been a tragedy if the sprinklers had not extinguished the fire. When responding to these calls, it is important to always be ready for the possibility that you may have a real emergency. I know that day when we were responding to the alarm location, I wasn’t thinking that we were going to be fighting a fire. We need to be ever vigilant and never let our guard down. That day, I will admit that I was not on the top of my game. I was taken by surprise when we were informed that there was a fire in the building.

|

| (6) Most times units arrive and the fire or emergency is not apparent from outside. |

One of the major problems with these types of buildings is that, unlike a private dwelling where the situation is apparent, there usually is no indication that anything is going on in the building (photo 6). The buildings are so large that unless the fire is out the windows, you will not know what is happening until you investigate the situation. This means that the minimum the units must do is the following:

- Enter the building lobby with all personal protective equipment including self-contained breathing apparatus, tools, hose, and so on.

- Go to the Fire Command Center and find the alarm panel.

- Locate the source of the alarm on the panel.

- The ladder company should take the elevator to two floors below the floor of the reported alarm.

- The engine company should find a working hydrant close to the fire department connection for the siamese (photo 7).

|

| (7) Siamese (FDC) must always be supplied. In New York City, the caps are color coded for easier identification. Yellow indicates that this system is a dual system, standpipe and sprinkler; green indicates sprinkler; red indicates standpipe. |

HOSPITAL KITCHEN FIRE

I was assigned as acting battalion chief for the night tour when we received a Class 3 alarm for a hospital. We received no additional information on the way to the location. When we pulled up, nothing was showing from the outside. I sat in the car, waiting for the companies to investigate the alarm. The engine company went to the lobby with rolled-up lengths of hose. I was expecting the truck to tell me that the alarm on whatever floor had gone off accidentally and that it was reset. What I heard instead was the ladder company calling to the engine company to start a hoseline for a fire in the restaurant kitchen (photo 8). He also called to the outside vent to take the windows, so I realized that we must have had a good heat and smoke condition. I immediately transmitted the alarm for a working fire in the hospital.

|

| (8) The luncheonette is in the bottom left. We had heavy fire in the kitchen area at 1800 hours. At the time of the fire, some surgeries were taking place one level below the fire floor. It was decided that it was better to shelter in place and not to disrupt the ongoing procedures. |

Like the most recent fire, I was faced with having to evacuate a good portion of the hospital that was exposed to the heavy smoke condition emanating from the restaurant. Just like the other fire, the hospital staff jumped into action and facilitated the evacuation. One of the major problems at this fire was that some surgeries were taking place in the vicinity of the fire; I had to make a critical decision as to whether to shelter in place or evacuate. I knew the firefighters would make quick work of the fire, so I decided that defend-in-place would be the better option. The firefighters knocked the fire down quickly.

What I learned from this situation is that it is difficult to even know where to start. You are being bombarded with so much, including the following:

- The fire.

- Smoke on numerous floors.

- Evacuation/defend-in-place.

- Strained communications.

- Span of control.

- Searches.

- Critical care patients.

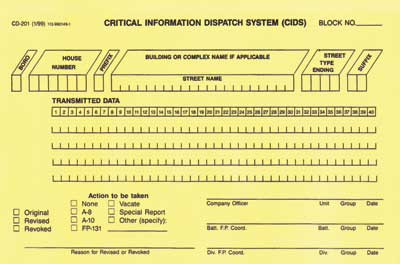

In the future, if I get even a trash fire in a hospital, I will transmit the second alarm and specifically the high-rise response. [In FDNY, we use a 10-76 signal (see sidebar).] You can never have too much help. Evacuating a hospital is like no other type of occupancy; most people need assistance in moving. As we saw in the Kalkata fire, many people are bedridden, and it could require up to four people to move one person.

HOSPITAL/SMOKE SHOWING

The last lesson learned is that a hospital has hazards that are too numerous to count. This fire is still a mystery, but I believe it was electrical. On arriving at the scene, every window in the kidney dialysis center was opened, and smoke was pouring out the windows. The patients had already been evacuated; just the staff had stayed behind. I sent the ladder company into the hospital to check out the situation; the smoke was already starting to dissipate. The engine companies hooked into a hydrant and started a dry hoseline, just in case. I did not transmit the alarm but decided instead to just keep the three engines and two ladders on scene.

We searched for more than an hour and never found the source of the fire. I was getting very frustrated. It was a Saturday morning, and no engineering staff was around. We found many rooms with loads of chemicals but not the source of the smoke. The smoke had totally dissipated at this point, and I decided that whatever had caused the smoke was no longer an issue, so I closed out the incident. I told the staff if they even get a faint odor of smoke to call us immediately.

OVERALL LESSONS LEARNED

These incidents yielded numerous lessons. First and foremost, there are no minor incidents when it comes to hospitals and nursing home

- I strongly recommend that if you have a hospital in your response area, you schedule a visit with the hospital staff and plan on doing a few multiunit drills. You should have a preincident guide in place for the hospital.

- On arrival to any hospital incident as the incident commander, your strategy should be the following: determine the fire floor, verify the fire floor, and determine if evacuations are in progress. If so, control the evacuations. (Through preincident planning, know the horizontal means of egress paths-i.e., whether from one fire compartment to another or into other attached buildings.)

- Gain control of the building services: elevators, HVAC system, communications, medical gas systems-i.e., oxygen, nitrogen, and nitrous oxide, for example; and fire pumps.

- Confine and extinguish the fire.

Fire No. 1

Looking back at this fire, one of the first things I would have done was to give the second alarm immediately. I was fortunate that the dispatchers transmitted the 10-76 immediately when I informed them that I was using “All Hands.” The hospital is in the northern part of the Bronx; even with the transmission of the 10-76, the units were going to be delayed because of the distance from Manhattan, where they are located.

I was unable to find the fire safety director (generally one is not required in New York City unless the facility has a fire alarm panel equipped with a two-way voice communication system). Most hospitals have an industrial hygienist or a general safety person who doubles as the fire safety person. I did find the building engineer, who was able to give me a lot of great information. He told me everything that was happening with the fire. We had a large generator on fire in the basement, and the sprinklers were containing the fire.

If I had found the fire safety director, besides determining the fire floor, I also would have asked about the following:

- What was the extent of the evacuation? (It was a major undertaking here at the hospital.)

- Were there any serious life threats? (The answer was yes; we had 165 people exposed in the critical care areas.)

- What was the status of the HVAC? (The engineer informed me that the HVAC was shut down; initially, the smoke was getting into the emergency rooms.)

These types of fires are extremely rare, but they do and will continue to happen. We need to expect the unexpected at every alarm and be prepared for it. Get help there early; you can always turn the units back. I would rather have the help there than need the help and not have it.

DAN SHERIDAN is a 26-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York, where he is a battalion chief. He has worked in the highly active units in Harlem and the Bronx for most of his career. He is a national instructor and the founder and chief operating officer of Mutual Aid Americas, an international nonprofit training group to assist firefighters. Previously, he instructed at the Rockland County (NY) Fire Academy. He is a frequent contributor to Fire Engineering magazine and has a monthly column on emberly.fireengineering.com. He authored Chapter 12 (Forcible Entry) for Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II.

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles

Fire Engineering Archives