BY KYLE SIMOK

On New Year’s Eve in 2015, at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California, Motley Crue’s legendary drummer, Tommy Lee, was riding his drum roller coaster above the audience when the system failed. He was strapped upside down, 40 feet above the audience floor, which was packed with more than 18,000 attendees. Uninjured and in good spirits, Tommy joked with the crowd while his production crew worked to free him for the next few moments. Within 20 minutes, he was brought back down and freed by the production crew.

But what if this scenario didn’t go this way in your response district? If the production crew couldn’t effect a rescue and your heavy rescue squad was on deck, 18,000 people were looking at you, and the production manager adamantly wanted to keep the show going, what would be your next move?

The fire service hasn’t had much exposure, if any, to train on specific incidents that occur during large-scale performances. It seems the only exposure first responders get is when catastrophic incidents happen, such as the stage collapse at the Indiana State Fair in 20111 or the 2013 structural collapse at the Apollo Theater in London, England.2

Has your fire department trained at your local venue? Has your fire department contacted the venue’s management or the local stagehands union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) to gather information on handling these incidents? Do you know where to go once you’re in the venue or to whom you should be talking?

Incidents during live performances have been ongoing since before there were fire and building codes to follow. Many current codes arose out of historic theater tragedies. These incidents involved catastrophic equipment failures, improper use of equipment, poor workmanship, severe weather, failed superstructure engineering, and security and fire code violations.

Theater Terminology

Like the fire service, the entertainment industry has its own terminology for locations in a given venue. The audience seating area is the house. The other areas including the lobby are the front of the house. Points of direction have specific names as well, like the fire service’s designation of sides of a structure at an incident. The stage floor is the deck. To the person looking at the house from center stage, to the left is stage left, to the right is stage right, and downstage is the area between that person and the front of the stage. Behind him, to the back wall, is upstage. Backstage areas differ according to the type of venue and the type of show.

|

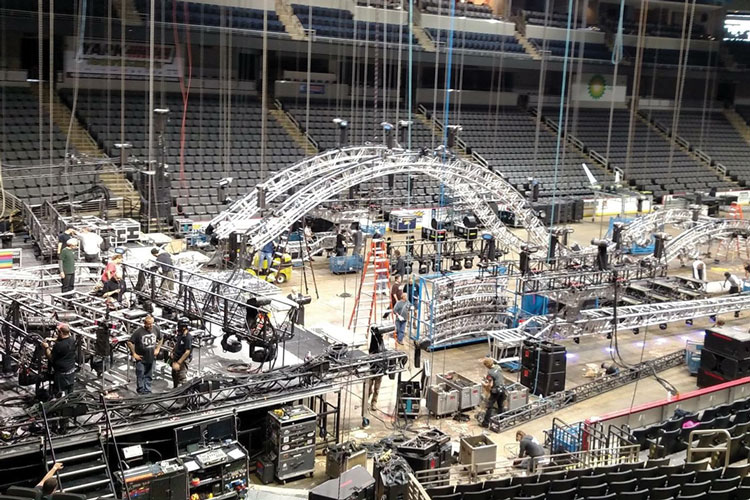

| (1-2) Motley Crue’s staging being loaded in at the Huntington Center, Toledo, Ohio. The truss work is the drum roller coaster that Tommy Lee rides during shows. (Photos 1-3 by Troy Roeske; photo 4 by author.) |

Typically, at a concert in an arena, the backstage area may be off to either side of the stage, where the show controllers may be staged. The show controls include the sound mixers and the lighting consoles and perhaps miles of cables. In a Broadway-style show in a theater, the show controls are in the booth in the back of the house.

Backstage

The theater’s backstage may include many integral points that fire service members should know. In many theaters, the high areas above the stage, the fly space, is where scenery, curtains, and actors may be raised or “fly up” into. The fly space is as tall as the stage opening or proscenium. Above the fly space is the ceiling grid, the weight-bearing area to which is attached all of the pulleys, sheaves, and motors that operate the items that may go into the fly space. The grid is permanently attached to the building’s superstructure beams and may be 80 to 100 feet above the deck. All of the cables and ropes run down from the grid along one side of the backstage area, typically stage right. The cables and ropes come down stage right to the fly loft. The fly loft is a suspended balcony backstage typically where counterweights are added and where crews may operate the lines, often manually. From there, the lines go down to the deck, where they attach to the pin rail to be tied off.

No two arena shows’ load-ins or setups are alike. Photos 1 and 2 show the load-in process, photo 3 shows the completed load-in of another event, and photo 4 shows the performance. Most concerts are loaded in and show-ready in about eight hours; the load-out or tear-down after the performance takes about five hours. All of the pieces come packed in 53-foot semitrailers. Most shows tour with 15 to 20 semitrucks. Arena shows use truss work to attach their equipment to the ceiling grid. The truss work is attached to the superstructure support beams with aircraft cable, which have chain lift motors attached to them to “fly” or raise the show’s truss work up to the ceiling area.

A single lighting fixture can weigh as much as 80 pounds. Put 10 of them together in a truss, and the weight quickly adds up. Think about that at the next Trans Siberian Orchestra show you go to at which a few hundred are hanging above your head.

Theater Management

Personnel in the theater world mimic the fire service’s command structure. The producers and promoters are the financiers who fund the show. Like the city administration, they front the money and provide the budget; they expect high returns on their investment from raving crowds at their shows. The production manager is the department chief; the stage manager is the battalion chief. The city chief doesn’t come to every scene, so the battalion chief usually runs the show. Under the stage manager is the design team, which consists of individuals who specialize in certain aspects of the show including lighting, sound, rigging, set design, and costuming. The design team mimics the incident management structure components in that all cooperate during an incident.

Under each of the designers are five to seven crew members or roadies, assisted by a local crew of stagehands from the IATSE union at each venue. The production crew travels with the show on tour. The venue personnel are the resident employees who manage your local facility.

The venue personnel include the management and department heads for marketing, event coordinators, operations and maintenance, box office, and security. The event coordinators are the liaisons between the venue and the production. When responding to your local venue for an incident, an event coordinator will most likely be the first to contact your crew. The venue operations team works with the production staff to set up items owned by the venue, like chairs on the floor and bike rack barriers for security.

Fire/Building Code Compliance

Catastrophic failure can occur from the improper use of equipment or the effects of natural forces. The engineering of venues and equipment can fail if used incorrectly. We can encounter concerns with poor security and accountability; our biggest concerns with special events involve local fire and building codes.

Experienced production crews will have an efficient team of engineers that has scrutinized the set and its components to ensure its safety and that it meets all codes. This covers the show’s liability and reliability. The production is responsible for the code compliance of the entire setup. If the crew working the show is inexperienced, it may use equipment not in accord with the manufacturer’s recommendations or local and international codes. This is apparently the major issue in most failures. In addition, several international organizations that cooperate with the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) have their own codes in the same way that the fire service has the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) standards. They include the Professional Lighting and Sound Association, the United States Institute for Theater Technology, and the Event Safety Alliance (ESA). Live entertainment productions are not exempt from following the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards or your local state regulations.

Equipment Failures

An equipment failure can result from an inexperienced crew’s using equipment not specifically engineered for staging and in compliance with the standards of the above organizations. In an August 2014 North Carolina incident, a crew used contractor construction lifts to support truss work used to hold up a roof over a stage. The lifts used had maximum capacities of only up to 500 pounds and are generally used by contractors to lift construction equipment into place.3 The lift manufacturer makes a line of tower lifts with outriggers and specifications designed for live entertainment use. The tower lifts used were not stable enough to withstand a 70-mile-per-hour (mph) wind gust that swept through the stage. Thankfully, there were no injuries in this case.4

An actress in Las Vegas’ Cirque du Soleil Ka fell more than 90 feet to her death in June 2013 from the venue’s grid above the stage to the stage deck. During a stunt scene in which the actress made a rapid ascent from the stage to the venue’s grid above the stage, she struck the grid, dislodging the wire cable from a sheave block and pulley.5 The system then failed as the cable rubbed against a sharp edge, causing it to shear and the performer to fall in front of the audience. OSHA assessed the Cirque production a penalty of $30,0356, and the MGM Grand Hotel received a fine of $14,000 after the investigation.7 OSHA’s investigation found that this incident was preventable since the venue and the show could have provided the actress with more training prior to her fall. This live performance was only her second time performing that part in the show. (5) The OSHA violations cited that Cirque failed to provide adequate protection to keep actors from striking the overhead grid, Cirque removed equipment from the site of the incident before the investigation was completed, and the fall protection program Cirque provided was found inadequate.8

Preventing Disasters

We can avoid these disasters by ensuring the rigging crew is properly licensed and qualified to do the work. The venue’s management or the local IASTE union should have records on file of training and licensure of the rigging staff. Riggers should have proper knowledge of all rigging components; should know how steel’s properties react under the stress of weight; and, above all, should recognize the design of the building to which they are attaching the rigging. Reputable riggers know the venue’s load charts and avoid exceeding the load limits. Reputable riggers also have engineers calculate the data to help them properly plan out the staging. Venue management typically provides the production team with load charts for the venue’s superstructure grid.

Natural Events

We can’t control the weather, but we can plan for incoming inclement weather and ensure that the staging, the event crew, and the venue’s staff are properly prepared to handle problems that could arise from bad weather. With modern technology, we can see the forecast days in advance. Wind gusts coming through outdoor venues generally don’t come as a surprise. Thanks to the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center, we know when storms are coming. The incident that struck the Indiana State Fair on August 13, 2011, was certainly avoidable.

The popular country band Sugarland was set to take the stage at 8:45 p.m. The event planning staff held meetings throughout the day. The event planning staff consisted of the production crew, the State Fair Commission, Indianapolis Fire Department (IFD), and Indiana State Police. (1) The IFD had preplans in place, but IFD’s preplans and tabletop exercises that were completed prior to the event didn’t account for severe weather. The weather was expected after the show would begin. They decided to start the show and allow the band to play before the weather hit. Staff scrambled to create evacuation plans for the crowd at the last minute; this information should already have been in the preplans. Communications between the production team and the fair commission undermined the weather reports. The organizers and show crew were adamant about starting the show even though a storm was quickly approaching. The announcer mentioned the impending storm to the crowd but gave no specific instructions on evacuation. Also, there was no plan in place to bring the stage truss down to ground level to prevent a catastrophic fall.

|

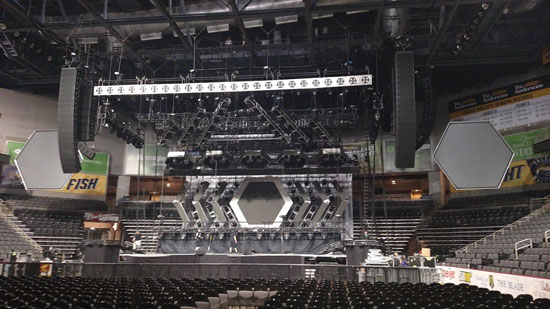

| (3) Country star Jason Aldean’s fully set up stage at the Huntington Center before the performance. |

At 8:52 p.m., when the show was set to begin, a 59-mph gust struck, bringing the rig down, crushing and trapping multiple patrons. Seven people died, and 100 were injured. (1)

The investigation by OSHA and an independent engineering investigation firm, Thornton Tomasetti, found that there was an insufficient lateral load resistance in place.9 The lateral load resistors were comprised of guy lines attached to concrete jersey barrier pieces to both sides and to the rear of the stage. Although this system could work in theory, the investigation proved that it could withstand winds of only 25 to 43 mph. Local codes required the structure to withstand 65-mph winds. (9)

The structure was engineered and designed to hold the weight and capacity of the band’s previous stage setup from 2010. The band had upgraded its set before this event, adding more weight loads without updating the structure’s capacities. No engineering paperwork for the structure was on file with the fair commission or in the hands of the IATSE Local 30’s rigging crew. (9) Thus, the fair commission and the IATSE union crew were unaware of the limitations of the guy line support wind risks. Proper preplanning, having an all-inclusive incident action plan (IAP), and communications with the production personnel before the day of the event can prevent hundreds of headaches.

Venue Engineering

When big structures are built, we trust the engineers’ calculations are correct and no failures will occur. Over the past 10 years, several venue superstructure collapses have occurred. Typically, arenas are constructed with a truss roof superstructure. On Sunday, December 12, 2010, the Minneapolis Metrodome’s fiberglass roof structure gave way under the weight of 16 inches of snow at 5 a.m. on the morning before a football game.10 This inflatable roof included two fabric layers: a Teflon-coated fabric and a patented sound-absorbing fabric. Air is pumped between the layers to keep the roof inflated, and the system functions to ensure that the pressure inside the dome is equal to or greater than outside forces. (10) Inflatable roofs are dome-shaped to ensure accumulated precipitation falls off. The Metrodome’s maintenance staff noticed a substantial sag; but because of the severe snowfall and high wind speed, they were unable to safely address the situation. No injuries occurred because it happened around 5:00 a.m., hours before the dome would be filled with football fans.

Another prominent superstructure collapse occurred at London, England’s Apollo Theater in December 2013. Because of weak and aging materials, the ceiling gave way during a performance with a full house. About 76 patrons reported injuries. (2) The theater was built in 1901, and the ceiling’s original composition was a mixture of cloth and plaster. Renovations were ongoing in other parts of the building, but they didn’t play roles in this collapse.

Security

Although the fire service usually does not cover this detail, it should not be an afterthought. Include law enforcement in your preplanning and IAP so they, too, can be prepared. Having all of your local public safety agencies and venue management involved in the IAP development and preplanning process will make your unified command structure more successful. (1) Some recent incidents involving security include the November 2015 Paris terror incident, where nearly 130 casualties were reported during a rock concert. A noteworthy domestic incident is the June 2016 Pulse Nightclub massacre in Orlando. These events prompted the ESA to further discuss with tour and venue management how to be better prepared. There’s no way of telling which event will be a target for terrorists, but ensure your local venues are properly preparing themselves by updating their security measures.

Fire Codes

In the Station Nightclub tragedy, on February 20, 2003, 100 concertgoers perished and another 100 were injured during a stampede toward the exit after a pyrotechnics mishap.11 The mishap occurred when a flame effect ignited some polyurethane foam, in place for sound attenuation. The crowd all at once made a mad dash for the only exit they knew of – the front main entrance door. Dozens became trapped in the doorway; many were trampled to death, and others perished from smoke inhalation.

By the time the first-arriving fire crew arrived on scene, the building was heavily involved. This incident prompted a multitude of changes in NFPA standards and codes in occupancies of public assembly.

|

| (4) Country star Jason Aldean’s fully set up stage at the Huntington Center during the performance. |

Studying this incident early on in my career reinforced the importance of situational awareness. Any time I go out anywhere, whether out to dinner with my family or to a show at a local concert hall, I immediately identify two or three additional exits in the event of an emergency. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigated the fire and issued many recommendations. (11) They included changes in standards for fire sprinklers in assembly occupancies, flammable materials use in assembly halls, and the implementation of inspections and strict code enforcement programs for nightclub occupancies. The report also called for changes in pyrotechnics use codes; occupancy limitations; and a focus on fire extinguishers – their availability, the travel distance to find one, placement, and training for staff members on their usage. (11) NIST’s report included a reconstruction of the fire to show conditions inside the structure, determine the area of origin, predict the survivability with the use of sprinklers, and analyze the egresses.

Another prominent fire occurred in a Thai nightclub on New Year’s Eve in 2009. Pyrotechnics ignited a blaze, leaving 66 dead and nearly 200 injured.12 The club owner blocked exits to prevent customers from leaving without paying their tabs. There were no emergency lights or exit signs or directional maps for the exits, although the local building code required them. The club was operated in a section of Bangkok where clubs were banned, and approving signatures for inspections and reports had been forged. (12) The occupancy wasn’t officially registered as any type of business but as a privately owned home. Because of this, Bangkok fire officials hadn’t performed any fire inspections.

The Final Curtain Call

When we buy tickets for an event, the last thing we want to think about is a catastrophic event occurring during the performance. But we need to be prepared. At any venue, especially one unfamiliar to you, keep your situational awareness and constantly be aware of your surroundings.

If you’re in charge of your department’s preplans, the above outline will help you start the process for your local venue. Visit the venue, and get to know the contact person – the fair board, the event coordinator, or the security manager. Ensure the venue is aware of your local permit and inspection process. Be strict and aggressive, but also maintain a friendly relationship between your fire department and the venue’s management. The economic impact the venue has on your municipality is exponential. Don’t force the business away, but don’t let it slide by on the law. Maintain the trust with the venue, and it will respect your decision making.

As you preplan, build your IAP, and execute tabletop scenarios at the venue; consider all of the worst-case scenarios. Plan for a building fire, a plague, and an active shooter incident. But also consider inclement weather – severe storms or dangerous temperatures. Include fire, EMS, law enforcement, public information officers, and the production and venue management teams in your tabletops. This will help with the unified command structure during an incident.

In your IAP, consider the special resources you may need in your response. Consider the uniqueness of stage incidents as opposed to typical rescue incidents, such as motor vehicle crashes and low-angle slope evacuation rope rescues. Stage incidents have the potential to involve more weight, trusses, high-voltage electricity, and a greater potential for more victim entrapment than the typical rescue call. You may consider including multiple heavy rescue squads, urban search and rescue resources, and heavy wreckers in your plan. When planning for an EMS mass casualty incident (MCI), follow your local MCI protocol, and know from where your resources will be coming. Predetermine staging areas for responding crews. Stick to your IAP during incidents.

Contact the event coordinator or the marketing manager at your local venue to preplan the facility and also to arrange for your presence when the next production is loading in. This will allow you and your crews to get a glimpse at what would be happening inside before it is filled to capacity.

References

1. Reith, Rita. E-mail, “Re: Info Request – Fire Engineering article on theatre & stage incidents.” Received by Kyle Simok, 5 July 2017.

2. Tighe, Siobhann. “Apollo Theatre Collapse Due to ‘old’ Materials.” BBC News. BBC News Entertainment & Arts, 24 Mar. 2014. http://bbc.in/2sR94dV. 9 Sept. 2016.

3. Genie Lift Specifications. ToolFetch.com. http://bit.ly/2umFb9Q. 10 Sept. 2016.

4. Smith, Tenikka. “Stage at Cleveland Co. Fairgrounds Collapses Saturday.” WSOCTV.com. WSOC-TV, 10 Aug. 2013. http://on.wsoctv.com/2uaxLWB. 10 Sept. 2016.

5. Katsilometes, John. “OSHA Fines Cirque Du Soleil and MGM Grand in ‘Ka’ Performer’s Death.” Las Vegas Sun. N.p., 29 Oct. 2013. http://bit.ly/2ufaQc6. 1 Sept. 2016.

6. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Inspection: 316844711-Cirque Du Soleil Nevada, Inc. Tech. no. 316844711. Nevada: OSHA, 2013. Ser. 0953220.OSHA Inspection Search Database. http://bit.ly/2uSQCCT. 10 Sept. 2016.

7. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.Inspection: 316844729-MGM Grand Hotel and Casino. Tech. no. 316844729. Nevada: OSHA, 2013. Ser. 0953220.OSHA Inspection Search Database. http://bit.ly/2t4n34l. 10 Sept. 2016.

8. Nevada, State of. Nevada Department of Business & Industry. OSHA Officials Conclude Fatality Investigation of Cirque Du Soleil Performer Sarah Guillot-Guyard. State of Nevada, 29 Oct. 2013. http://bit.ly/2ujGqXb. 1 Sept. 2016.

9. Nacheman, Scott G. August 13, 2011. Collapse Incident Investigation. Report on Findings to the Indiana State Fair Commission. Thornton Tomasetti, 12 Apr. 2012. http://bit.ly/2tJuT1K. 1 Sept. 2016.

10. Wiegler, Laurie. “Tearing into the Metrodome: Are Other Air-Pressurized Stadiums Unsafe and Outmoded?” Scientific American. Nature America, 20 Jan. 2011. http://bit.ly/2ufuMvM. Sept. 2016.

11. Grosshandler, William L, Bryner, Nelson P, Madrzykowski, Daniel M, and Kuntz, Kenneth. Report of the Technical Investigation of The Station Nightclub Fire. Rep. no. 2. Vol. 1. Gaithersburg: National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2005. National Construction Safety Team Act Reports. NIST NCSTAR 2. http://bit.ly/2t4W6x5. Aug. 2016.

12. Head, Jonathan. “Disturbing Details in Thai Blaze Inquiry.” BBC News, Bangkok. BBC News, 4 Apr. 2009. http://bbc.in/2uSHPRA. Aug. 2016.

KYLE SIMOK is a firefighter and emergency medical technician in northwestern Ohio and a theatrical lighting designer. He is also a fire instructor at a local community college, an American Heart Association basic life support instructor, a freelance lighting designer, a stage rigging specialist, and a stagehand.

Responding to “Routine” Incidents at Large-Event Venues

Be Ready for the “Big One”

Responding to Target Buildings in a Terrorist Attack: Are Your Crews Prepared?

Pre-Staging Equipment Before Major Events

Where’s the Party?

Fire Engineering Archives