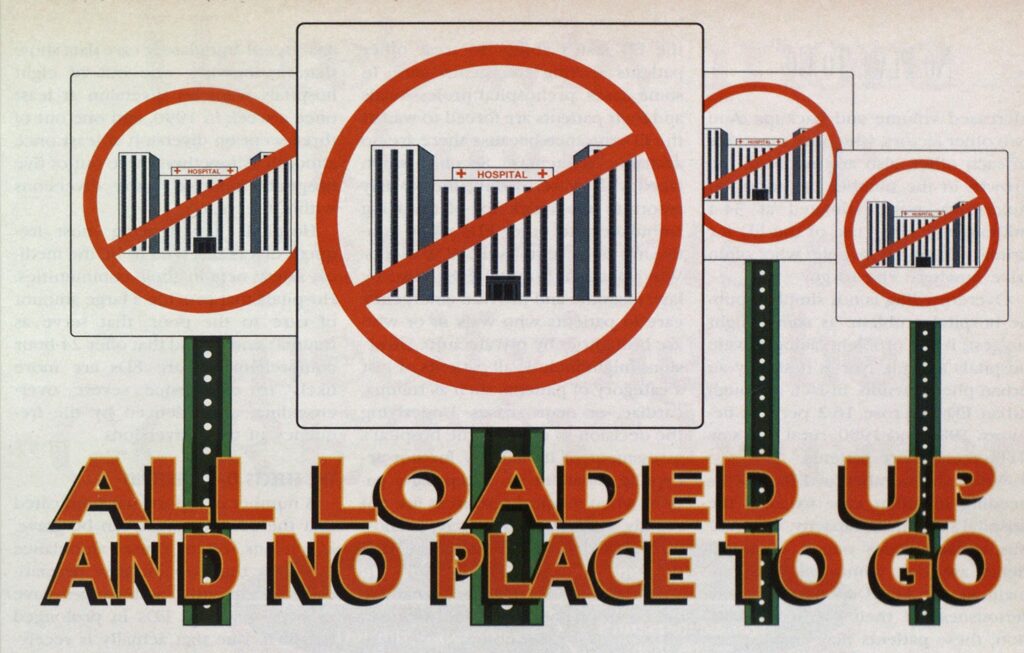

ALL LOADED UP AND NO PLACE TO GO

Blow-bys; bypasses; medical diverts; trauma diverts; conditions green, yellow, and red. Radio airwaves across the country are full of such terminology. Sound confusing? Just add it to the varied and inconsistent use of and response to these terms, and the confusion multiplies.

The terms refer to temporary hospital closures and ambulance diversions— a source of considerable frustration for prehospital providers. And the problem is not new. Approximately 12 years ago, New York City hospitals began diversions. Still, hospital closures are a serious concern for paramedics who have to run around trying to find an open emergency department (ED). Reports of compromised patient care, strained relationships between EMS providers and hospitals, and extremely dissatisfied customers are on the increase. At best, diversions bring unnecessary’ stress, confusion, and inconvenience; at worst, diversions jeopardize optimum emergency medical services response time and patient care.

DIVERSIONS

Diversion is the only prehospital solution to hospital overcrowding. EDs in all parts of the country are in gridlock. They’re overcrowded and overw helmed —some routinely, some periodically. In a recent study of some 800 community hospitals conducted by the American Hospital Association’s Division of Ambulatory Care, more than one-third reported overcrowding on a weekly basis, and more than half said they w’erc overcrowded at least once a month.

The explosion of ED visits itself would not necessarily produce a crisis, but given the available resources, it has. Overcrowding represents the culmination of many of the failings of our social and health-care systems. As our population grows older and sicker, the health-care delivery’ system in this country will be stretched to the breaking point. And, there are other reasons for overcrowding. There is an increase in both the number and severity of trauma cases, tied to various forms of social pathology—drugs, violence, and poverty all play a part. A lack of available inpatient beds— whether due to insufficient capacity or insufficient staffing—is another factor. No doubt the AIDS epidemic has made a significant contribution to increased volume and backups. And two other factors, which are functions of each other, also are involved: the growth in the number of uninsured Americans, now estimated at 34.4 million, and rising use of the ED for primary care by people who often have nowhere else to go.

Overcrowding is not simply a public hospital problem, as some might suggest; it is a problem facing private hospitals as well. Nor is it simply an urban phenomenon. In fact, although urban ED use rose 16.2 percent between 1980 and 1990, rural EDs saw 21 percent more patients.⅜

When the number of ED patients needing inpatient care exceeds the hospital s inpatient capacity, two serious consequences occur. First, patients awaiting admission must remain in the ED. Depending on the seriousness of their medical condition, these patients may require disproportionate attention and thus limit the ED staff’s ability to treat other patients seeking emergency care. In some cases, prehospital professionals and their patients are forced to wait at the ED entrance because there are no available stretchers. Second, when faced with overcrowding, the ED may resort to the quick fix of diverting ambulances to other EDs while continuing to accept “walk-in” patients. Why? Because hospital EDs must, by law, examine and provide emergency care to patients who walk in or who are brought in by private auto. Diversions might include all patients or just a category of patients such as trauma, cardiac, or neuro cases. Underlying the decision to divert is the hospital’s assessment of its liability for not accepting a patient vs. accepting a patient when medical resources are not readily available. Either way, prehospital providers are caught in the middle.

Diversions, like ED overcrowding, are common nationwide, occurring in all regions of the country. No geographic areas are spared. Preliminary analyses of ambulatory care data show that, nationwide, one out of eight hospitals went on diversion at least once a week in 1990, and one out of three went on diversion at least once a month. Altogether, three out of five hospitals reported some diversions within the year. ‘

Hospitals experiencing most frequent diversions tend to be the medical safety nets in their communities. Hospitals that provide a large amount of care to the poor, that serve as trauma centers, and that offer 24-hour comprehensive care EDs are more likely to experience severe overcrowding, as evidenced by the frequency of their diversions.

THE EFFECTS OF DIVERSIONS

A number of reports have indicated that the consequences can be grave. Diversions often cause ambulance transport times to increase dramatically.5 Frequently, ambulances have to bypass several EDs in prolonged transit to one that actually is receiving. In Chicago, Illinois, if one trauma center is on diversion, patient transport times may be extended up to 30 minutes before reaching the next closest trauma center.6 The practice of diversion causes ambulances to travel greater distances, resulting in higher fuel cost. It also removes advanced life support ambulances from their response districts, contributing to longer response times. But most important, for the patient being diverted, the time to definitive diagnosis and treatment is prolonged.

Families also are affected. Believing that their family member was transported to one hospital, they arrive to find that the patient was rerouted to another hospital. In some cases the hospital staff has no know ledge of the patient or where the patient might be. When family members do not find their loved one, typically they are not upset w ith the hospital that closed but take their anger out on the paramedics and the EMS providers.

Finally, those hospitals that receive the diverted patients, who may not be insured, encounter additional and unanticipated strains on their resources and may face large, unrecoverable costs.

THE LEGALITY OF DIVERSIONS

Although the courts have not yet determined whether diversions violate federal “anti-dumping” laws, a number of experts believe that without pre-established policies, diversions are not appropriate. In response to questions raised regarding the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 (COBRA) and subsequent amendments of 1989, Health Care Finance Administration Associate Regional Administrator Clarence J. Boone made his position clear: “If all the community hospitals have reached an agreement regarding diverting patients to another hospital because the emergency room is operating at or beyond maximum capacity, then the ambulance personnel can inform the patient or the patient’s representative of this situation. If the patient and/or the representative still insists on a particular hospital, then the patient has the right to select that hospital.” Boone further indicated, “It is not appropriate to refuse to accept ambulance patients who request to be transported to a hospital which is on diversion’ or is not accepting patients, even walk-ins, in the emergency department.”8

Mississippi attorney Armond Moeller echoes the necessity for diversion policies: “There are situations in which diverting a patient to another hospital without medical screening is appropriate. However, ambulance services and hospitals are well advised to have written agreements outlining diversion policies.”9

A WORKABLE DIVERSION POLICY

Proactive planning and open dialogue are keys to a workable diversion policy. Variations between hospitals and communities must be anticipated and addressed if the plan is to succeed. The patient’s hospital choice, the patient’s medical condition and location, and the law must be considered in any diversion policy. The policy should include, at a minimum, the notification process for informing KMS providers when hospitals request patient diversion and specific identification of which hospital will be accepting the diverted hospital’s patients. EMS providers also should require that the agreement contain specific acknowledgment from the hospital that the patient will be accepted on the request of the patient or depending on the patient’s medical condition, regardless of the hospital’s diversion status.

Moeller suggests that typical patient destination guidelines include the following factors, ranked in decreasing order of importance:

1. Patient choice!location of personal physician. The patient or his/ her guardian has the right to choose a nearby hospital. Also, if the patient has a personal physician and the EMT, patient, or guardian knows the hospital at which the physician is on staff, this information should be used in determining the patient’s choice.

2. Patient type and hospital capability. Hospitals varr in their capability for caring for certain patient ty pes. Categorization of the emergency medical capabilities at the various hospitals should be established. Then the patient’s condition may be used to determine hospital destination.

3 Medical direction. Local medical authorities may direct that the patient be transported to a certain appropriate facility based on the patient’s immediate needs.

4. Geographic location. Hospitals with similar capabilities located in the same general area may be chosen based on a random scheme. If adequate hospitals with adequate facilities are not located in the same general vicinity, their distance from the patient’s location may be used as a determinative factor.10

These considerations generally reflect appropriate medical practice. However, the overcrowding problem and resulting ambulance diversions can affect these factors significantly and limit the public’s timely access to quality health care. In November 1991, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) released a detailed policy statement regarding handling diversions and destination policies. The statement encourages each EMS system to develop mechanisms that do the following:

- Identify situations in which necessary resources are not available and temporary ambulance diversion is acceptable.

- Notify EMS system personnel and providers (prehospital and hospital) of such occurrences.

- Provide for safe, appropriate, and timely care of patients who continue

- to enter the EMS system during these periods of diversion.

EMS agencies can protect themselves only if they abide by local, state, and federal policies regarding ambulance diversions. And, if written policies do not exist, they should push for the development of such policies.

Do diversion policies work? Santa Clara County, California, which includes the city of San Jose with nearly two million people, overcame an enormous ambulance diversion problem that included hospitals selectively diverting patients. Before July 1990, the average hospital ED in Santa Clara was closed about 10 days each month, with monthly highs of 27 days. Abuse of the system was so rampant that hospitals not only diverted ambulances on individual cases to select the patients they wanted (e.g., the paying customers), but they also piggybacked other closings to avoid being overwhelmed by an influx of patients.

To break their diversion cycle, Santa Clara EMS officials threatened the hospitals to either solve the problem voluntarily or face a ban on all diversions and transfers. Since no one liked the idea of a complete ban, all parties agreed to cooperate, and a specific timetable was set to fix the system.

Santa Clara instituted a policy whereby hospitals are either completely open or completely closed, no in between. Hospitals on diversion status lose all privileges, including transfers. The county also installed a computerized EMS network notification system to help enforce the new closing policy. The system continually tracks all closures within the county and provides monthly reports with clear-cut data for evaluation.

Today, Santa Clara diversions have been greatly reduced. Eleven out of 12 hospitals now average less than a 2 percent closure rate, and the 12th hospital averages 1 1 percent. Within one month, the countywide number of monthly closure hours dropped from 1,153 hours in June 1990 to 378 hours in July 1990. The situation continues to improve. During 1991, the lowest number of countywide monthly closure hours was 104 and the highest was 566.

Area hospitals in Providence, Rhode Island, developed a similar diversion plan. Under the plan, participating hospitals agree that when more than two of the six hospitals go on diversion at the same time, all of the hospitals open their HDs until the situation can be resolved. The hospitals also meet by conference call twice daily to discuss HD conditions and determine diversion priority among the hospitals during the following 12-hour period. The open communication has fostered trust and alleviated the diversion problem because the hospitals are more aware of citywide ED patient loads.

LONG-TERM SOLUTIONS

The factors leading to overcrowded HDs are complex, and the solutions to the problems will not be easy. The nation’s health-care policy makers must address some of the fundamental system problems that are at the root of the overcrowding and diversion issues. Providing a basic level of health insurance for all citizens, improving funding for emergency and trauma services, reducing nonemergency use of HDs, removing the financial disincentives to hospitals providing emergency care, and increasing the support for prevention of injuries in the first place all have been mentioned as basic steps for resolving the health-care dilemma. But few are optimistic about the immediate future, and it is very likely that the situation will get worse before it gets better.

Fortunately, overcrowding has captured the attention of the media. National television news segments have shown ambulances driving from hospital to hospital seeking care for patients. Cover stories of Time, Newsweek, and other national magazines have described in graphic detail the horrendous collapse in emergency care across America. This continued coverage should increase public awareness of the problem, maybe even press the issue closer to longterm resolution. In the meantime, communication, cooperation, and planning at all levels within the EMS system are essential measures to help EMS providers cope. ■

References

1.Nordberg, M. “Overcrowding: The ED’s Newest Predicament.” Emergency Medical Services (1990): 19(4):33-47.

2. McNamara, P. “The Sagging Safety Net.” Hospitals (Feb. 20, 1992): 38.

3. Ibid, p. 26.

4. Ibid, p. 40.

5. “Dangerous Detours: Ambulance Diversions Stall Patient Delivery.” JEMS (1989): 11:43-47.

6. Neely, KW, AM Bennison, JE Acker, et al. “Computerized Hospital On-Line Resources Allocation Link (CHORAL): A Mechanism to Monitor and Establish Policy for Hospital Ambulance Diversions.” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine (1991): 6(4):459462.

7. Wagner, L. “Hospitals Feeling Trauma of Violence.” Modern Health Care (1990): 20:23-32.

8. “Hospitals Cannot ‘Close’ to Ambulances.” Management Focus (Summer 1991): 1,3.

9. Moeller, AJ. “Managing the Changing Legal Environment.” Lecture to the EMS Management Academy, Allis Plaza Hotel, Kansas City, Mo, Oct. 1991.

10. Ibid.

11. “Guidelines for Ambulance Diversion/Destination Policies.” ACEP News (Jan. 1992): insert.

12. “Are Ambulance Diversions Necessary’ or Problematic?” ED. Management (1992): 4(3):37-38.

13. Johnson, J. “Rhode Island Initiatives: Hospitals Share MRls, ED Patient Loads.” Hospitals (1991): 65:30,31.