BY ROBERT A. NEALE

The U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) National Fire Academy (NFA) has a 33-year history of delivering executive leadership and advanced technical training to representatives of America’s fire and emergency services. Now, as it plans for the future, NFA faces new challenges as the demographic makeup of its student population changes.

The NFA’s congressional mandate is “to advance the professional development of fire service personnel and of other persons engaged in fire prevention and control activities.”1 Over its history, the NFA has observed a demographic and technological evolution in how students absorb course content: Today’s adult learners are using a combination of face-to-face instruction, paper-based and electronic self-study, blended learning2, asynchronous and synchronous mediated learning, social media (Web 2.0), and mobile learning to achieve their learning objectives. The NFA is responding to the changes in an incremental fashion.

HISTORY

At its founding, the NFA was built on a brick-and-mortar model: Adult learners from federal, state, and local jurisdictions (and occasional foreign students) are selected to attend a variety of classes at the school’s facility at the National Emergency Training Center (NETC) in Emmitsburg, Maryland, where they interact with one another (networking) and professional instructional staff. The NFA continues to develop and deliver face-to-face, on-campus curriculum for those courses that may address unique or emerging national issues; that are focused on advanced leadership, executive, and technical training; or, by the nature of their content, that are too expensive for state and local jurisdictions to replicate.

In one form or another, the NFA always has employed a complementary distance learning approach to its course deliveries either through sharing its curriculum with state and metropolitan3 fire service training organizations to leverage their resources or through partnerships with colleges and universities to deliver self-study correspondence courses. Through these partnerships, the NFA trains approximately 59,000 students per year in traditional classroom settings at the NETC and sites throughout the United States. As part of this relationship, the NFA categorizes its face-to-face content delivery methods into “NFA-sponsored” courses that are federally funded and “state-sponsored” courses, where the state training partners bear the costs of delivering NFA curriculum.

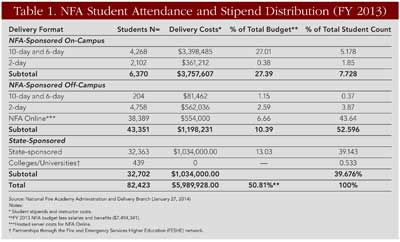

The NFA plays a significant role in connecting Department of Homeland Security (DHS) training and education doctrine-such as the National Incident Management System, the National Infrastructure Protection Plan, and the National Response Framework-to state and local first responders. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2013, 7.73 percent (6,370) of NFA students attended classes in residence at Emmitsburg; 45.7 percent (37,664) attended classes delivered at the state, local, or college level; and another 46.6 percent (38,389) took training through NFA Online.

In recent years, the NFA has expanded incrementally into different learning modes to take advantage of technology and new delivery methods while not creating a “seismic shift” in its traditions. Its electronic learning management system, NFA Online, hosts 62 self-study classes that reach an estimated 40,000 students each year. The NFA also is experimenting with asynchronous mediated learning where adult students participate in college-level education through combined electronic discussion boards, e-mail, and NFA Online courses.

By the end of 2015, it is expected at least another 15 self-study, blended, or mediated courses will be added, many of which are being developed by staff.4 Traditional face-to-face courses now are offered in two-, six- or 10-day formats to meet student schedules: There are approximately 60 courses delivered on campus in this mode; another 45 are delivered by NFA in off-campus venues.

For NFA on-campus courses, students are eligible to obtain one travel stipend per fiscal year. The travel stipends were authorized by Public Law 93-498 that created the U.S. Fire Administration and National Fire Academy. (1) The purpose of the stipend is to support student attendance at on-campus courses. Course materials and lodging are provided to the students at no cost while they are in residence at the NETC. Table 1 summarizes the National Fire Academy FY 2013 student attendance and stipend/instructor cost data for the variety of delivery formats currently in existence.

As new courses are developed and existing courses modernized, the NFA Curriculum Management Committee has adopted the following informal policy: If the nature of the course content demands a geographically diverse classroom population to enhance student interaction or there is a unique feature of the NETC to which students need physical access,5 courses will be built around a traditional face-to-face format for delivery in Emmitsburg. These on-campus courses generally include blended elements such as precourse online exercises or postcourse online evaluations. All other courses are to be developed or revised for the maximum flexibility of face-to-face or other learning methods.

Anecdotally, students report that one of the key reasons they attend the NFA on-campus deliveries is the ability to network with other students from around the country. Students often report they “learn as much outside the classroom” from their peers as inside the formal classroom setting. Instructors build in expectations that students will learn from their peers both inside and outside the classroom. The NFA’s adult learning model promotes and relies on lively interaction among students facilitated by experienced and competent instructors.

The nature of the NFA student population differs from a traditional community college or baccalaureate student body. It is a “targeted” population of adult emergency first responders and their management staff: Students have some current nexus to fire service, emergency medical services, disaster preparedness and response, or other agencies involved in all hazards threat response and mitigation. Generally, students either are full-time employees of these agencies or are highly committed volunteers who want to increase their professional skills.

The NFA may be unique in the federal government because its specific mission is training persons who are not federal employees. In current jargon, the NFA is an “outward-facing” training and education entity rather than “inward-facing.” Unlike similar DHS training organizations, such as the Transportation Security Administration, Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, Emergency Management Institute, Center for Domestic Preparedness, and Customs and Border Patrol Academy, the NFA’s primary mission is to train state and local first responders and their leaders, not federal employees. Although these other entities offer some training to state and local representatives, their principal student population is federal employees.

However, NFA students do not present an entirely homogenous population. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 38 percent of 18 million students enrolled in the nation’s colleges and universities are ages 25 years and older.6 By comparison, NFA student ages range from 18 years old and upward; it is routine to have students in their 20s through 60s in the same classroom. This diversity creates a training challenge, as many of the students have been educated throughout their lives by different teaching methods. Many students are intimately familiar and at ease with modern technology; others are reluctant to adopt it. As one example, beginning in FY 2013, the NFA committed to transferring its traditional paper-based student manuals to electronic readers. As of August 7, 2013, up to 85 percent of students who have been afforded the opportunity to “go digital” (depending on the course) report they prefer to use the electronic manuals, leaving merely 15 percent who prefer paper-based products (J. Glass, National Fire Academy personal communication, August 7, 2013).

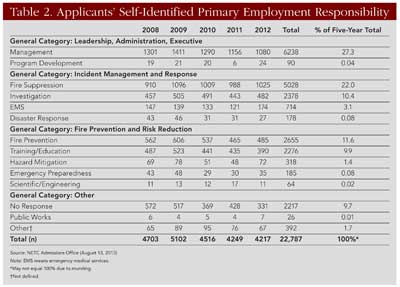

Furthermore, the NFA target student population is skewed by a preponderance of applicants whose main vocational focus is in emergency response and operations, which is reflective of the typical demographic of America’s fire and emergency services. Table 2 represents a five-year summary of NFA application data for six- and 10-day on-campus courses based on students’ self-identified primary employment responsibility. These data are important to NFA staff as they plan and develop course materials and delivery methods, as they represent the imperative training audience and potential “market demand.”

According to a joint USFA/National Fire Protection Association study, there are an estimated 1.1 million firefighters in the United States that comprise the potential NFA student audience.7 By some estimates, only 1.36 percent of all firefighters are employed in fire prevention services,8 but this is an important USFA target audience to help fulfill its congressional mandate to “educate the public and overcome public indifference as to fire, fire prevention, and individual preparedness” and reduce community risk against all hazards. (1) The NFA consistently tries to balance popular customer demand with providing leadership through strategically important courses intended to prevent, prepare for, and respond to the nation’s all hazards threats. Courses with titles such as “Command and Control of Incident Operations” appeal to a larger potential audience than an equally important course entitled “Leading Community Risk Reduction.”

RECENT RESEARCH

To get a picture of the changing adult learner, in August 2013, the NFA conducted a literature search of contemporary scholarly research on adult and professional education. Using several easily accessible search engines on the World Wide Web (ERIC, EbscoHost Academic, USFA WorldCat, and Google Scholar), the NFA searched on the following key words: “course delivery methods,” “blended learning,” “mixed delivery,” “online versus traditional,” “online versus classroom,” “blended best practices,” “online best practices,” “educational content delivery methods,” “adult classroom education,” “adult classroom learning,” “adult online dropout rate,” “adult distance training attrition rate,” “experiential learning,” and “best teaching adult method.”9 To ensure a contemporaneous source of material, searches were limited to the years 2008 to 2013. Research was conducted by the USFA National Fire Programs Learning Resource Center staff and me. NFA Curriculum and Instruction branch staff were invited to review this paper’s draft, and several contributed substantial comments.

Findings

Adult education and training remain under constant and rigorous scholarly analysis. Depending on how one frames a Web-based search phrase, Google Scholar alone returns more than 20,000 “hits” of books, academic reports, journal articles, and other research. Educational scientists debate the variety of methods available to deliver content to ensure learning transfer occurs from the source to the student. A short-term survey of recent literature shows that there is no single instructional method that serves all adult audiences and a healthy scholarly debate over the benefits of each learning method. Search results respond to how the search question is framed.

Research reports delimited to not older than 2008 quantitatively appear to study mostly distance learning methods, but that may be a result only of the field’s relative newness compared to long-standing teaching (traditional) methods. A brief survey of articles from 1999 to 2009 contained more content on the transition from classroom to distance education. As one example, Pérez-Prado and Thirunarayanan (2002) concluded, “Courses that require students to develop empathy or other affective orientations may not be suitable candidates for web-based distance education.”10 With academic success possibly hinging on the discipline or course material, this is certainly an area of distance learning in need of further research.”11

Ross-Gordon found that the body of research suggests that while adult learners desire flexibility (like that offered through the variety of NFA delivery modes), they desire structured instruction. (6) Each of the delivered modes NFA employs (from face-to-face to self-study) are structured on sound and well-tested instructional design principles.

According to one teaching method meta-analysis of 58 separate adult education studies:

Results showed that all six adult learning method characteristics [instructor introduction and illustration, learner application, evaluation, reflection, and self-assessment] were associated with positive learner outcomes, but that methods and practices that actively involved learners in acquiring, using, evaluating, and reflecting on new knowledge or practice had the most positive consequences on learner outcomes.12

Another federal institution, the National Defense University, recently spent two years evaluating its curriculum and delivery methods. Based on its mission of developing national and international executive strategic leaders, it elected to keep traditional face-to-face courses because of the needs of strategic learners to meet and share ideas in a real-time collaborative.13

Most of NFA face-to-face courses use “performance-based” instruction. In this manner, the NFA is able to address training to solve job performance problems and not just a lack of requisite skills or knowledge. That immersion training cannot be accomplished online. The experience NFA provides allows the learner to be immersed in the job by doing the job-e.g., participate in command and control or EMS scenario-based exercises, excavate the evidence from a live-fire scene, or process post-fire forensic evidence.

Bejerano14 posited that one of the problems with distance learning is the lack of sufficient student support:

In face-to-face classes, students have their classmates, learning centers on campus, professors’ office hours, tutors, and teaching assistants to support and help them with their various learning needs. These resources guide them, clarify and reinforce the material, and allow them to succeed in their education. Teachers understand the value of these resources and forms of support. As online courses become more popular, teachers are trying to find new ways to incorporate these resources and forms of support into their class. The problem is that student drop-out is increasingly high in online courses and these resources and forms of support need to be more effective in combating student attrition. (14, 1)

Bejerano also noted over the timeframe of her study that the student dropout rate is increasingly high in online courses. (14) According to Lee and Choi’s 10-year survey of online dropout rates in post-secondary education, the evidence suggests that “online courses have a significant higher student dropout rate than conventional courses.”15 Lee and Choi identified 69 separate factors that influenced students’ ability to complete online classes for which they had enrolled. (14, 593-618) Jones (2006) reported that “of students who begin online courses, 50% do not finish due to lack of support and problems inherent in online learning”16 A headline in The Chronicle of Education online magazine that asked “Preventing Online Dropouts: Does Anything Work?” was answered curtly: “Nothing works.”17 (In two recent NFA mediated online courses, the student dropout rates over 12 weeks were 44 percent and 41.9 percent.18 By comparison, the average annual dropout rate for NFA on-campus courses from FY 2010-2012 was 0.59 percent.

Maintaining the quality, effectiveness, and integrity of the NFA training programs is done through resident course delivery of practical and simulation-based exercises. This method provides a safe training environment while providing a realistic field experience for the students. Students may make errors without suffering life-threatening consequences. Practical exercises emulate highly dangerous scenarios while enabling student learning in a safe and controlled environment. This training can measure the student’s knowledge for point of possible perception, point of actual perception, reaction time, reaction decision, and point of no avoidance for each particular set of conflicts. This enhanced training capability augments existing first responder skills, allowing the student to face the consequences of his/her decision and allowing for immediate instructor feedback, thus producing a better trained and better prepared responder. The stimulus that instructors observe by responding to student classroom behaviors leads to greater exploration of the content. Furthermore, face-to-face instruction allows instructors and trainers to provide immediate feedback and support for students’ special or functional needs.

Displaying 1/2 Page 1, 2, Next>

View Article as Single page

Fire Engineering Archives