NFPA 1999: A STANDARD OF PROTECTIVE CLOTHING FOR EMS OPERATIONS

The proliferation of infectious agents has put emergency personnel increasingly at risk from exposure to deadly diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis in the course of their normal duties. The International Association of Fire Fighters estimates that one out of every 15 firefighters has been exposed to a communicable disease. More than 30 percent of these exposures involve hepatitis B or HIV. This threat of . exposure mandates that emergency responders approach incidents with a new awareness with regard to their practices and the protective clothing they wear. Despite new regulations and guidelines, little information was provided to help emergency responders select appropriate protective clothing.

NFPA 1999, Protective Clothing for Emergency Medical Operations, recently developed by the NFPA Technical Committee on Fire Service Protective Clothing and Equipment, addresses specific concerns of emergency responders with regard to protection against liquid-borne pathogens that can be encountered in numerous types of emergency responses where exposure to blood and other body fluids is probable or possible. NFPA 1999 fills a significant gap in the industry for defining the minimum required performance for most emergency medical operations. This is particularly true since the new Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) “Final Rule on Protecting Health Care Workers from Occupational Exposure to Blood Borne Pathogens” (29 CFR 1910.1030) contains no specific provisions for determining acceptable protective clothing performance. The Final Rule states:

When there is occupational exposure, the employer shall provide at no cost to the employee, appropriate personal protective equipment, such as, hut not limited to, gloves, gowns, laboratory coats, face shields or masks, eye protection, and mouthpieces, resuscitation hags, pocket masks, or other ventilation devices. Personal protective equipment will be considered appropriate only if it does not permit blood or other potential infectious materials to pass through to or reach the employee’s work clothes, street clothes, undergarments, skin, eyes, mouth, or other mucous membranes under normal conditions of use and for the duration of time which the protective equipment will he used.

Under this rule, firefighters and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) who provide emergency patient care are considered health-care workers and must have a program in place to limit their exposure to contact with blood and other bodily fluids. This program must address the selection and use of appropriate protective clothing.

NFPA 1999 was written as a tool for preparing an infectious disease control program. The standard establishes protection against liquid-borne pathogens and defines liquidproof performance for protective clothing used in emergency medical operations consistent with the OSHA Final Rule. As a consequence, it is important that emergency response personnel understand NFPA 1999 and know how to apply it within their organizations.

CLOTHING TYPES

NFPA 1999 addresses three clothing types: garments, gloves, and facewear.

Garments. They can be full-body clothing that covers the wearer’s torso, arms, legs, and head or partial-body clothing, such as jackets, aprons, sleeve protectors, and shoe covers. Both types of clothing must provide complete wearer protection for the portion of the body covered.

Gloves. They must be foil-hand elastomeric gloves designed for physical and barrier protection that also offer high tactility and dexterity. These gloves must go beyond the wrist and provide equal protection for all areas of the hand.

Facewear. This equipment includes items such as masks, goggles, safety glasses, and respirators. The important factor here is that the face-protective device must cover all mucous membranes on the front of the face. This may be accomplished by one or more facewear items, such as goggles in combination with a face shield.

PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS

NFPA 1999 sets minimum performance requirements for each type of protective clothing based on minimum user protection. The following areas of clothing performance are addressed: clothing liquidtight integrity, material barrier resistance, material durability, and clothing function.

Each area of performance is applied to the three clothing types. For example, garments must show liquid-tight integrity through a special test designed to demonstrate resistance to liquid penetration. In this test, garments placed on a mannequin, are exposed to a surfactant-treated water spray and must prevent liquid from reach ing the mannequin’s skin. Only the intended areas for protection must offer this performance. In a similar requirements gloves are tested for overall integrity by filling them with water and observing for leaks. This follows a procedure developed^ by the Food and Drug Administration and prescribed as a standard test method by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Facewear integrity is* evaluated through a modified water-spray test where the spray is directed toward the headform of the mannequin on which* the facewear is placed.

Garments and gloves must demonstrate appropriate durability through the mea-⅜ surement of material physical properties. Garment materials are tested for tensile strength, burst strength, tear resistance, puncture (snag) resistance, and seam/closure strength.

Each of these properties and their selected minimum required values reflect garment performance expected by wearers under normal conditions. NFPA 1999 also provides optional tests to show how well the material acts as a barrier following abrasion and continued flexing. In addition, comfort offered by the garment can be assessed in a test that simulates how well the material “breathes.”

Gloves also are tested for elongation properties, cut and puncture resistance, heat degradation, and resistance to alcohol. Each of these conditions represents factors or hazards that can potentially lead to glove failure and exposure of the emergency responder. In addition to glove durability, NFPA 1999 addresses the sizing and usability of gloves. Manufacturers must provide emergency medical gloves in at least five sizes. Gloves also are tested to determine whether they interfere with wearer tactility and dexterity and must allow emergency responders to perform normal hand manipulations with no loss of function.

THIRD-PARTY CERTIFICATION

NFPA 1999 requires third-party, independent certification of manufacturer products to show their compliance. This means that medical clothing manufacturers must have their products tested by outside laboratories and their production inspected in a quality-assurance audit. Clothing meeting those requirements have a special label indicating their compliance. The standard tells the exact terminology users should look for on the label to ensure certification. Looking for this label and the certification mark is the only way end users know that the protective clothing is in compliance with the standard. It is not enough for manufacturers to represent their products as meeting NFPA 1999; they must meet all requirements for certification and demonstrate that compliance as verified by independent, third-party certification.

DEFINING LIQUIDPROOF PERFORMANCE

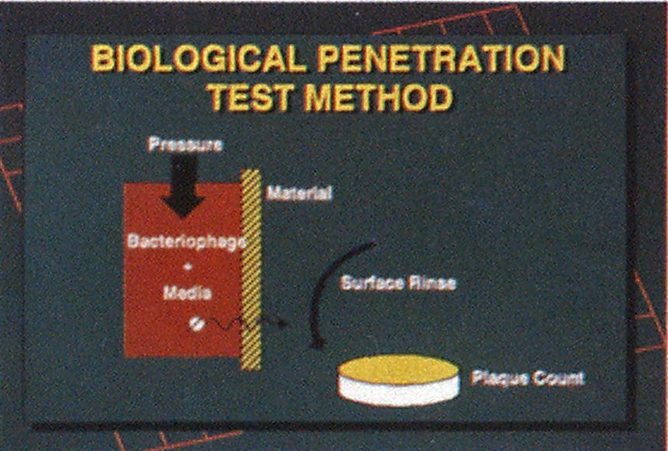

The most significant tests in NFPA 1999 are those used to establish how well clothing materials provide a barrier to liquid-borne pathogens. The standard uses a test based on the use of a microorganism that simulates the hepatitis and AIDS viruses. This procedure was adopted as a standard test method by ASTM ES 22. The microorganism, bacteriophage Phi-X-174, is approximately the same size and shape as the hepatitis C virus, which in turn is slightly smaller than the hepatitis B and AIDS viruses. The test is conducted by placing a liquid containing the bacteriophage in a test chamber. The test chamber holds the liquid containing the bacteriophage against a clothing material sample for one hour. Pressure simulating stresses on the material during use is applied for a portion of the test period. If liquid is seen penetrating the material, the material fails. If no liquid is observed on the viewing side of the material, the surface of the material is rinsed with sterile liquid, which then is examined for bacteriophage. If a bacteriophage is found in this assay, the material also fails. The assay is so sensitive that it is capable of detecting a single penetrating virus, thus providing a clear definition of liquidproof performance.

While the bacteriophage test may not seem to simulate the exact likely conditions of exposure in the length of time and the pressure applied, it has demonstrated extremely good correlation with practical-based clothing tests, such as the “elbow lean” test. In this test, synthetic blood approximating the physical characteristics of blood and other body fluids is applied to a surgical sponge. A sample of clothing material with a sheet of blotter paper over it is placed on top of the surgical sponge. The sample then is pressured with an elbow or finger, simulating normal in-use pressures. If any liquid penetrates the material sample and stains the blotter paper, the material has not prevented exposure to the synthetic blood and therefore fails the test.

Small droplets of blood are capable of carrying thousands or millions of viruses. Even a pinpoint of blood can carry hundreds or thousands of individual viruses, which, if given the right route of entry, can potentially infect the wearer. The elbow lean test, in conjunction with the bacteriophage-based test used in NFPA 1999, effectively demonstrates material performance as a barrier to virus penetration, visually and on a microscopic level.

CURRENT CLOTHING AND NFPA 1999

With the establishment of NFPA 1999, much of the clothing traditionally used in EMS or patient-care settings does not offer acceptable performance. NFPA 1999 poses tough requirements on clothing used in emergency medical operations. Many of the gloves, garments, and facewear currently in practice are unlikely to meet these requirements.

During the development of NFPA 1999, the U.S. Fire Administration supported an independent study in which a number of clothing tests were performed to help establish the performance criteria used in the standard. Tests were selected for performance areas in which EMS clothing, gloves, and facewear traditionally failed or caused problems for the wearer.

Based on a survey among EMS department members, the NFPA subcommittee^ identified clothing that gave acceptable or unacceptable performance. These clothing items then were tested and the results compared to establish data separating clothing with acceptable performance from that with unacceptable performance. In this way, the minimum performance requirements were established for each clothing type and performance area.

For example, a number of outerwear garments were tested to the prospective requirements of NFPA 1999They included common medical materials such as disposable fabrics and reusable cotton/ polyester blends. Other materials used in chemical protective clothing and other applications also were submitted for evaluation.

On the basis of physical properties and bacteriophage penetration, only one material was found to meet all the requirements of NFPA 1999. Of the other materials tested in the USFA study, those with a continuous film prevented viral penetration but failed the physical property requirements. Most of the common medical materials in use today are porous and therefore cannot possibly prevent blood splashes and microorganisms from penetrating. And some lightweight disposable materials fail because they lack what users deem appropriate durability under EMS working conditions—i.e., they easily became torn or punctured.

Similarly, several gloves were evaluated. Among them were the gloves typically used in the medical community, such as latex exam and surgical gloves. Gloves constructed from polyethylene and vinyl materials common in medical use also were tested. Many of them are single sized and come out of tissue-like dispensers. In addition to the common medical gloves, other products were evaluated, including a heavier latex glove and a thin-gauge nitrile rubber glove.

Understandably, most medical gloves are easily punctured and therefore did not meet the minimum NFPA 1999 performance criteria. Other gloves found to tear easily or break when being donned failed the physical requirements. Some gloves, though appearing to provide a continuous film barrier, were found to actually leak virus. Only two gloves tested—the heavyduty latex and the thin-gauge nitrile gloves, from one manufacturer—passed all barrier and physical property requirements. Only the thin-gauge nitrile glove, however, met the needed performance for dexterity and tactility. The heavier latex glove, while durable and resistant against bacteriophage penetration, is too cumbersome for many EMS patient-care functions.

These results demonstrate that most products currently marketed for medical protection do not meet NFPA 1999 requirements. This does not mean that the NFPA requirements are overly strict. They were designed with user protection in mind, and the overwhelming number of wearer complaints about the performance of protective clothing in emergency medical operations is simply additional justification for these performance requirements. This standard was not proposed to accommodate existing products but to encourage use of products that provide a minimum level of protection to emergency responders.

NFPA 1999 has been in place since late 1992. Currently, the newly revised edition of NFPA 1500, Fire Department Safety and Health Programs, specifies requirements for using emergency medical protective clothing and cites compliance of protective clothing with the requirements of NFPA 1999. Organizations that comply with these standards are well on their way to fulfilling the federal regulations specified in 29 CFR 1910.1030 for selecting “appropriate” protective clothing.

The impact of this standard will be significant. Like other NFPA protective clothing and equipment standards, manufacturers will have to improve their products to increase protection to an acceptable level. Users benefit by having protective clothing products that have a known level of protection assured by NFPA 1999 certification.

Several clothing manufacturers are in the process of trying to meet NFPA 1999 requirements, but the standard will remain only an interesting curiosity unless users specify compliance with NFPA 1999 when they procure emergency medical’ protective clothing. NFPA 1999 will not guarantee protection from all medical hazards, but it will provide a solid basis for selecting protective clothing, and it will help limit the potential for exposure to bloodborne pathogens.*