Nation’s Largest Wildland Fire of ’77

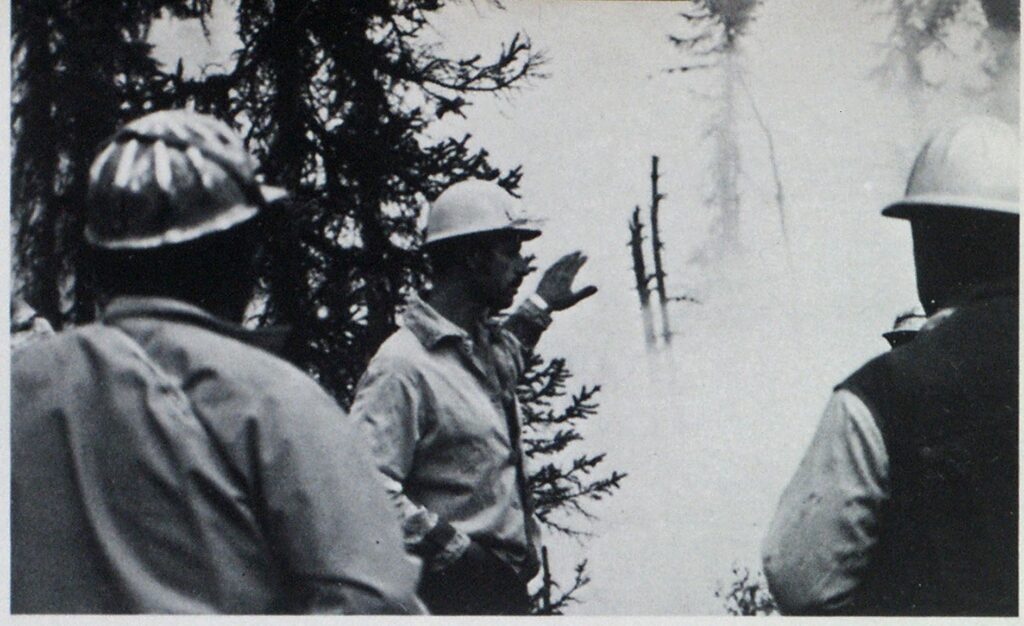

bureau of Land Management photo

In a year of catastrophic wildland fires across the country, Alaska once again had the dubious honor of being host to the nation’s largest wildland fire.

The Bear Creek fire started last August 6 as a routine 5-acre lightning fire and developed into a monster of 361,600 acres. This fire taxed the resources of the Alaska fire forces to the extreme and presented a variety of unique problems.

The 1977 fire season in Alaska, as in most other parts of the country, was one of abnormal high temperatures and lower than usual rainfall. The problems started in early June with fires scattered from Fort Yukon across central Alaska to the McGrath area. Fires were noted to be unnaturally rapid in their spread characteristics. There were 57 lightning fires in June and 306 in July.

From July 21 to 31, 22 fires started that eventually exceeded 1000 acres each. On July 31, Alaska got 26 new fires. Ten were extinguished that day, but 62 fires were carried over to August 1. A smoke pall covered the area from 149° longitude westward to 163°.

Fire all in remote areas

These fires were almost all in areas without any roads, hundreds of miles from bases and primary communications. Many fires were beyond the range of helicopter flights.

Fire control officials, along with a multitude of resource analysis persons in both the Fairbanks and Anchorage districts met around the clock, analyzing the fires as they were reported. Priorities were set and attack plans laid, with the highest priorities given to threatened native villages and high-priority public interest lands. Many fires were not manned because higher priority lands were involved in fire at the same time.

Every available fire fighter was pressed into service to meet the emergency. Mutual-aid agreements were invoked and various municipal fire departments assumed protection responsibility near their areas to free Bureauof Land Management (BLM) personnel to respond to the massive fires in the interior.

It must also be remembered that the lower 48 states were also being taxed to the utmost with fires coast to coast, so the outside aid usually available to Alaska was no longer available.

Fire spreads rapidly

From the 5 acres first spotted, the Bear Creek fire in the Farewell area, approximately 200 miles northwest of Anchorage on the western edge of the Alaska Mountain Range, extended to 12,000 acres in two days.

One of the first major problems for Kay Johnson, chief of the Anchorage District of the BLM division of fire management, was that all his fire forces were already committed on fires from the Bering Sea to Canada. Overhead teams, fire fighters, aircraft, and logistics support materials had to be diverted from other fires to this new one. The immediate concern was to protect the villages of Medfra and Nikolai, but even this presented a problem since smoke placed a lid over the fire, making its exact size, movement, and condition unknown immediately and keeping aerial retardant aircraft and helicopters grounded.

The smoke conditions were serious in Medfra, Nikolai, Farewell and McGrath, and due to w ind currents and shifts, in Mount McKinley Park and towns east of the Alaska Range. At times the smoke caused aircraft to go to instrument approach to Fairbanks, several hundred miles to the northeast. Smoke effectively closed the base fire camp at the Farewell FAA landing strip for days at a time. The thermal column from this fire went several thousands of feet high, so high that it generated its own thunder and lightning storm.

Unbroken fuel cover

The fire was burning in an almost flat area on the western side of the great Alaska Range. The only elevations were on the southeast corner, where a slight moraine ran along the Kuskokwim River.

Near the point of origin and running north to south was virtually unbroken fuel cover, primarily black spruce, with some birch along the rivers. Toward the north and northwest, the fuel cover became tundra and evolved into swampy areas, which continued on for many miles. The Kuskokwim River ran northwesterly about 12 miles east of the point of origin and the Windy Fork River about 12 miles to the west.

After considerable analysis of the fire area, the fuels, and a multitude of environmental considerations, a fire plan was developed to allow the fire to burn eastward to the Kuskokwim River and westward to the Windy Fork River. It was also decided to hot-spot the north side but allow the fire to burn into the marshy areas.

It was decided to use backfires and burnouts to make the river breaks really secure. All fuel between the rivers and the main fire was burned. Because no roads or suitable trails existed and a great expanse was involved, the burnouts were accomplished by extensive use of an air-delivered firing system. This airborne firing was extremely successful in this task—as it had been on several other major fires during the year. This system will likely be a primary tool of remote fire fighting in Alaska for many years.

Plan defense of villages

Positive defense plans for Medfra and Nickolai, villages north of the fire, were developed by using structural fire officers from the Municipality of Anchorage as advisers. This program of mutual aid is demonstrative of the type of cooperation among the various fire agencies needed to combat this fire.

Anchorage Fire Captains Jim Blake and Terry Ellis were borrowed by the BLM to develop defense plans for these villages, now only about 12 to 15 miles ahead of the fire front. These officers prepared primarv and secondary defense plans which are being considered by BLM fire officials as prototypes to he used whenever villages are threatened by fire.

The primary concern for Fire Boss Jack Lewis, a veteran Alaskan fire fighter, was the south side of the fire. The fuel cover continued all the way to the Alaska Range, with few natural barriers to stop it. With the fire’s base camp located at the FAA Farewell field, with a major FAA facility at the site, and a large private facility at Farewell Lodge (a major center of big game hunting and fishing), it was decided that a maximum effort would be made to stop the fire in this area.

Since manpower was insufficient to make any direct attack, the available personnel were used as highly mobile strike forces that used helicopters and river boats to reach and contain the most troublesome areas of the fire.

The use of bulldozers on Alaska fires is very tightly restricted due to the fact that their trails may take several hundred years to regrow to a natural state. Therefore, studies were made by a raft of resource persons before the decision was made to use dozer trails to stop the fire. Because of the seriousness of the fire and the potential damage if the fire were not stopped, it was decided to use bulldozers along the south side of the fire.

Five large bulldozers were airfreighted to the Farewell field and driven cross-country to the fire. The first attempted line was overrun by the fire, and the crews had to be pulled back several miles. The construction of a second line progressed for several days but ended when the fire flanked the line along the Windy Fork end.

Once again, the units were pulled back and after about three more days of work, a line was tied together between the Kuskokwim and the Windy Fork, roughly about 30 miles of line. It was this line that finally stopped the fire.

The fire stopped at the Kuskokwim River on the east and at the Windy Fork on the west, with the exception of an area at the extreme northwest corner of the fire where it jumped the Windy Fork and burned to the Middle Fork River.

On August 13, the fire boss declared the fire under control and on August 25, the fire was de-manned.

Go short on rations

Personnel endured a fire fight where rations were limited for days because smoke prevented aircraft from Hying into the fire area. Smoke also prevented an accurate survey of the fire. There was a lack of personnel and equipment because of the other serious fires and a shortage of almost everything due to the monumental logistics problems, bears, and even a buffalo stampede through a fire camp.

Overhead teams working on this fire had mostly been working fire for many days, some for over 60 days straight prior to the Bear Creek fire. Therefore, the fatigue factor for the overhead teams was tremendous. In order to keep a reasonably fresh team on the fire, five teams were used during the 20 plus days this fire was manned.

When the monster was finally tamed, several historic roadhouses on the famous Iditarod Trail had been destroyed, vegetation around this dog-team trail was burned completely, forage for moose and the P’arewell bison herd disrupted, salmon spawning areas possible affected for several years, and the subsistence hunting and trapping grounds for the area’s natives considerably disrupted.

However, not one life was lost, no serious injuries were sustained by either residents or fire fighters.