By DAVID POLIKOFF and FRANK RICCI

At an emergency scene, the incident commander (IC) can operate from inside a command vehicle or outside at a designated command post (CP). As with the question of using a smooth bore or a fog nozzle, the fire service is divided on this fundamental issue. But as Tom Brennan once said, “You don’t have to be wrong for me to be right.” The fire service could learn a lot from that sentiment.

The Command Post

The National Incident Management System (NIMS) defines the incident command post (ICP) this way: “The ICP is the location where the Incident Commander operates during response operations.” The key to remember, whether operating inside or outside, is there can be only one CP. Although its location can be changed, ideally it should be positioned just outside the hazard area—in the front of or near the main access to the area—and be properly designated.

Command Presence

Some try to mystify command presence as an abstract trait that some may or may not have. This is not the case. Command presence can be taught and learned. To build your command presence, you have the foundation as a student of your craft and a competent fire officer. You also have to work to consistently improve yourself. Command presence is increased or decreased depending on several key factors, including your reputation and how calm you are under stress.

Reputation

Your reputation on the job is based on your knowledge, training, education, treatment of people, trustworthiness, and experience. In command, you cannot “fake it till you make it”; your subordinates will see right through you. If you want to be a trusted command officer, obtain a variety of experience.

(1) Photo by Andrew Cooke. (2) Photo by Christine Ricci.

Have you commanded an engine, a truck, and a rescue squad during your climb up the career ladder? Have you been assigned to busy companies, or have you hid on the outskirts of the districts that get the first-due work? There is a significant difference between going to fires and going to fires as first due.

One of our best friends started his career on a busy first-due company and, after a few years, transferred to a squad in the city. When he was promoted, he was asked if he wanted to stay on the squad. After a long talk, he took the age-old advice of “Go back to a busy first-due company; make your bones; and, after a few years, go back to the squad.” He has credited this advice as key to building his credibility on the job. He is one of our go-to officers who has earned the respect of his peers and command officers.

Calm Under Stress

The late Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini of the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department said, “If it is an emergency to us, who are we going to call?” If you cannot remain calm under stress, no training will ever help you. The goal is to channel Darth Vader from Star Wars—he never ran or even raised his voice. When he walked into a room, he owned it, and even if he was losing, he was always in control. Yes, he was able to choke his subordinates, and your only power may be to transfer someone, but always keep in mind that all eyes and ears are on you.

(3) Photo by David Polikoff. (4) Photo by Eric Rammacciotti

Decentralize Your Fireground

Make it a rule to assign your command officers as they arrive on scene to any area you can’t see. When creating a division or a sector, announce its area of responsibility and the officer who will fill the role (based on the function and your incident action plan). Announce which companies will be reporting to that officer.

As those crews move from that division or sector to rehab, the CP, or staging, the companies’ disposition should then be announced. Although it is good to have one senior advisor assigned to the CP, you want to break up the opinion brigade, so trust them and give them an assignment. This will also build your command staff.

Face-to-face reports help to cut down on radio chatter, but if the report will have an impact on other companies’ tactical or task decisions, transmit the face-to-face report over the radio.

Radio Demeanor and Control

Be calm, clear, and certain of your message. In the New Haven (CT) Fire Department, we teach our command officers to look away from the incident for a few seconds when transmitting. This allows you to transmit your message without taking in additional information. Use simple, easy-to-understand words and phrases that convey confidence. Make the company repeat its message if you didn’t understand it.

Also, if a company radios to command without going through its division or sector, politely correct the caller as to whom he should report. This will cut down on future radio chaos.

Compare all radio reports with what you are seeing. If the reports do not match the conditions, you need to make changes.

Benchmarking

Whether you are in command inside or outside, benchmarking is critical at every incident. Note when lines are in place, and confirm searches by geographic location.

Also, ensure there is a running clock, and institute appropriate notifications from dispatch at preselected intervals. Your department should also have established protocols for conducting personnel accountability, size-up, progress, and under-control reports.

Logistics

Everyone wants to go to your fire, so invite them. You can’t play catch-up. You need to ensure you have resources in reserve. You can always return them when the incident is deescalating; however, you can’t put them into the game if they’re still five minutes out.

Do you have enough companies if a Mayday is called or if the exposure becomes involved? Remember, you are in command, and the success or failure of the firefight will fall at your feet.

Keep in mind that there is no politician or policy that says you can’t call for the resources you need to keep your members safe while operating on scene.

Running Command Outside

In the Northeast, it is common to run command from the outside. We like to be close so we can use our senses of sight, sound, and smell in evaluating the conditions under which our members are operating. Being out front permits direct interaction and ensures that radio reports are not lost in translation. However, there are also drawbacks.

Receiving informal information through what you see has advantages that cannot be matched when you are remote from the building. It also allows for the quick interaction of face-to-face reports from division officers. In photo 1, the battalion chief gives the IC a face-to-face report on interior conditions in front of the building.

When running command from outside a vehicle, you must follow some parameters. I (Frank Ricci) have seen chief officers moving around the fireground. It becomes difficult when units need to report face-to-face and the IC can’t be found, resulting in more radio traffic.

Chief officers are still firefighters at heart and can get drawn into helping with tactics. Command officers must understand that they should work with their minds, not their hands.

Announce the location of the outside command board, and keep it stationary. A stationary command board provides an easily identified location for the IC (photo 2).

Some departments use a green light to designate the CP. When the IC takes a lap around the building (a 360° walk-around) or goes into an adjoining building to evaluate the rear, the IC should assign a member to staff the command board. The IC does not always have to do a 360° himself as long as he has a report on the rear from the roof personnel. Command may also assign the 360° to a division officer or to the rapid intervention team boss to report on conditions. Ideally, the same company officer or person should conduct the subsequent 360° or reports on the rear so this person can compare conditions and evaluate if they are improving or getting worse.

Command Aid

The ability to communicate with limited distractions is critical. Units should be able to hear the IC, and the IC should be able hear the units. To ensure that critical messages are not missed, assign an aide to monitor radio traffic using a headset. This member can also assist with member location and accountability on the fireground.

RELATED: COMMAND POST LOCATION | How to Operate a Command Post | Accountability: Positions in the System | THE PORTABLE COMMAND POST: COMMANDER-FRIENDLY

One of the biggest distractions is a fire company that tends to creep closer toward the CP. The best way to prevent this is to have a command aide keep companies at least 10 feet back. Alternatively, the IC can establish a staging area and designate a staging manager. Training companies on ICS and proper discipline will help the command staff. Companies should only be in four places: assigned, staged, in rehab, or at the CP ready to be assigned.

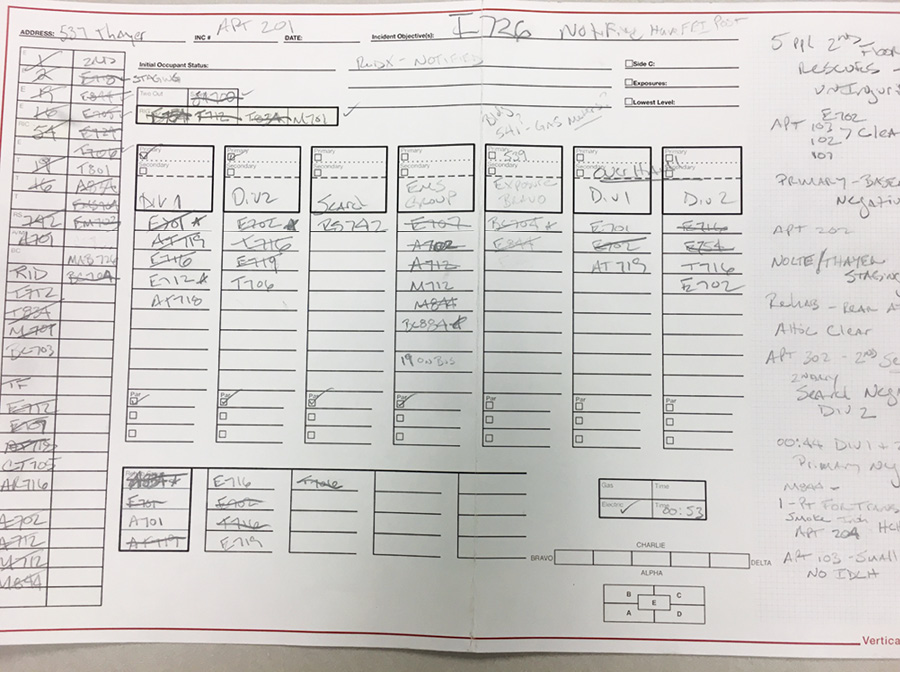

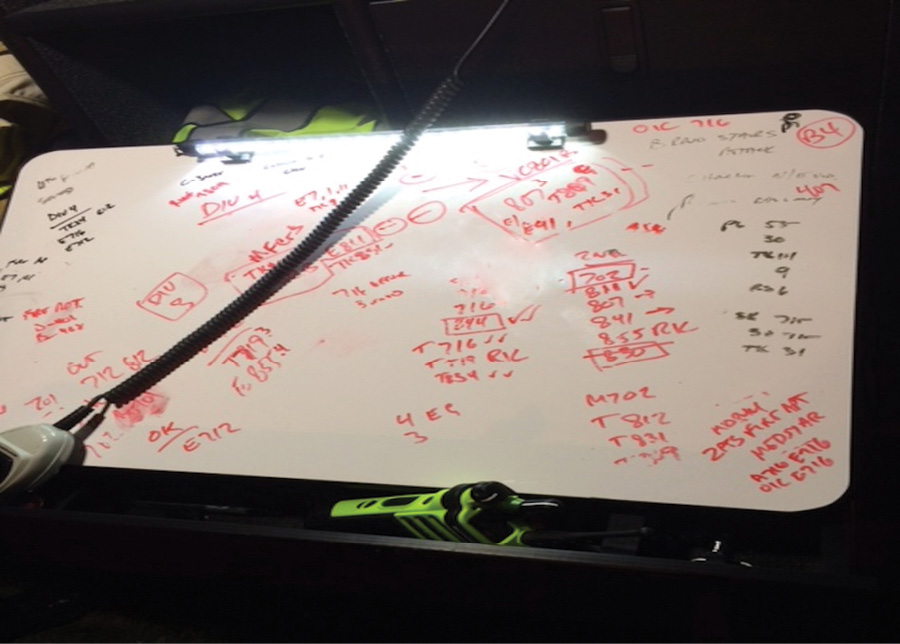

Tactical Worksheets

Whether commanding inside or outside, tactical worksheets are a must. Paper tactical worksheets are the best tool to track units on the fireground, and you can file them away after the incident (photo 3). Tablets are becoming more popular, and we expect they will be used more as the technology advances. Using a dry-erase board (a white board) may seem like a good idea, but in the rain, information can be accidentally washed away, or someone can easily brush up against it and the information can be lost. You can also run out of room on it, and the IC will have to start writing in different spots things that only an officer can decipher. The white board in photo 4 was used during a three-alarm fire. Although the IC may be able to decipher it, other command officers may have trouble.

A good tactical worksheet lets any command officer read it and know where all units are on the incident scene. When drawing a diagram of the incident, ensure it is oriented to the same vantage point as the command board. This will aid in understanding when command is transferred.

Limiting Distractions

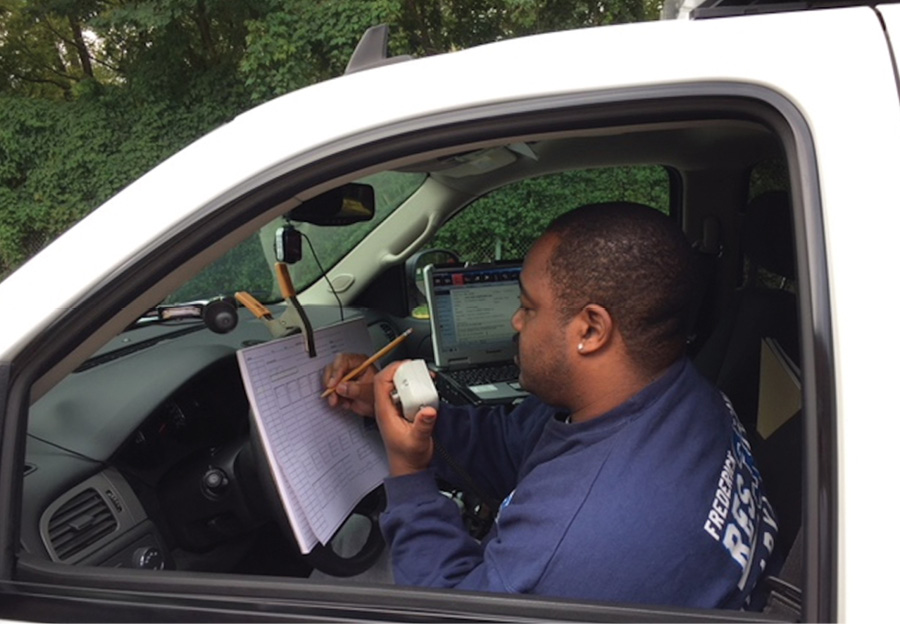

Most incidents are noisy. The last thing any command officer wants is to miss a critical message (a Mayday, a changing fire condition report, or a changing building conditions report). The CP should be close enough to the incident to see as much of it as possible but not so close that an IC can be distracted. An earpiece or headphones will assist with blocking out a noisy incident and allow an IC to hear units when they call (photo 5).

(5) Photo by David Polikoff. (6) Photo by David Polikoff.

Building occupants or owners are another distraction. Assign someone to gently keep them and others attempting to approach you out of your way. Such individuals may be from the Red Cross, the fire marshal’s office, or your emergency operations center. This person will explain what is going on and focus on a positive customer experience at the worst possible time. When you are running command outside of a vehicle, it is imperative you continually monitor the incident and do your best to limit your distractions.

Informal Information

An advantage to being outside of a vehicle is witnessing first-hand information that is not filtered through the radio. You get a feel for the true conditions from the faces of the troops—for example, an officer who is not ready to go to rehab but the look of the crew dictates otherwise. It is also easier at times to hear and see what is happening during inclement weather.

Weather

When choosing to run your command outside, be mindful of the weather. Dress according to the weather conditions. Being too cold, wet, or hot can be a distraction. I have seen ICs wear full turnout gear in August to run a command. This practice is a good reminder of what your people are going through and that you must rotate crews so they do not overheat. Also, it allows for a quick transition to a division officer if command is transferred to a senior chief.

A good IC will be aware of the weather without being uncomfortable and without risking distraction. Ensure you are protected from the elements while maintaining your CP.

Running Command from Inside

When running command from inside a vehicle, follow the same parameters as when running command outside. The IC should be stationary and the CP well defined by a green light. The vehicle must also be set up with the capability to allow the IC to effectively use tactical worksheets. Even if you are positioned in a car, you still will have to limit distractions (photo 6).

Operations

Running command from inside a vehicle allows the IC a relatively distraction-free environment. The IC can listen to radio channels and track personnel with a tactical worksheet without being distracted by the weather. Keeping the vehicle’s windows up can block out noise and allow the IC to concentrate on running the incident. Face-to-face communications are still possible but in a more orderly manner.

Command Aide

A command aide or a second command officer in the vehicle can act as a filter. Running all face-to-face communication through the aide may reduce distractions and avoid missing vital radio transmissions. Departments will build command platforms for the IC to run, but in the process they add many devices to “assist” the commander—several radios monitoring different channels, cell phones, and mobile data computers. Although all this technology can aid the IC, it can also be distracting. Most firefighters believe they are great at multitasking. But in reality, your scenes can get saturated with input and you will be forced to filter out information. It becomes easy to miss critical information.

Limits of Vehicle Command

Some of the cons to running command inside a vehicle’s climate-controlled environment include reduced situational awareness of outside conditions and sounds. You may be tempted to listen to too many radios or focus on all the technology. Don’t become so focused on your worksheets that you miss what is right in front of you. The opposite is true with commanding outside: Don’t get so focused on what’s in front of you that you miss a key component on the tactical worksheet.

Lesson from the Street

A few years ago, I (Dave Polikoff) was the commander of an apartment fire. When I arrived, the fire was on two floors and was moving to the third floor. I quickly called for a second and third alarm because of the uncontrolled fire and the high outdoor temperatures. I was trying to listen to the radio, track my units, and stage the third alarm. I had several people trapped on their balconies. I had my hands full, but I felt I was working the incident well.

At one point, I had to pull companies back to the stairwell because of advancing fire conditions. I called for a personnel accountability report (PAR) from all units. I asked the first-due rescue squad for its PAR; they advised they could not account for two members because they had split up their crew. My tactical worksheet had their crew on the second floor, but they were actually on the second and third floors.

Although all personnel were quickly found, I was upset that the crew had split its personnel without telling command. Later, when I reviewed the audio of the fire, I found that the rescue squad crew did tell me they were splitting their crew between two floors. What was worse was hearing that I had acknowledged their transmission.

Missing that transmission made me realize I am not as good at multitasking as I thought I was. This can happen no matter how you run your command, inside or outside. You must be aware of your surroundings and filter out as many distractions as possible. Keep in mind, managing resources and tracking crews are two of your biggest responsibilities.

Whether Inside or Outside

Whether your department gives you the option or dictates one style over another, you must be committed to excellence and continue to grow. Your number-one concern is concentrating on the incident and the well-being of your personnel. Be aware of the distractions that can creep into your CP. Delegate to aides or other commanders to lighten your load. Information comes quickly on the fireground, whether it’s from the technology at your fingertips, the personnel on scene vying for your face-to-face attention, or units calling on the radio. Use each incident as a learning tool.

Senior Advisor

Many departments are working to build and mentor upcoming command staff. This is critical. If you are a ranking officer and you arrive on scene and declare that you are serving as a senior advisor, you must not give any orders. Your role is to be married to the IC and work directly with him. If the incident is rapidly escalating and getting away from command, you may choose to have command transferred to you or you may be able to give advice and walk the IC through to a successful outcome. The key is, once in an advisory role, do not give orders; you will only be undermining the person you were attempting to support.

After the Alarm

Get audio copies of your incidents, listen to your communications, and conduct a quick after-action review with your company officers before demobilizing your scene. Always start with what you would have done differently or better to encourage open communication. Doing so will allow you to pick up on areas you can improve and hone your skills as a leader on the fireground.

DAVID POLIKOFF is a 30-year veteran of the fire service. He is a battalion chief for the Montgomery County (MD) Fire and Rescue Service. Polikoff is an instructor with Capitol Fire Training LLC. He is a past presenter at FDIC and co-host of the Fire Engineering radio show “Politics and Tactics.” Polikoff is a volunteer with the Sykesville Freedom District Fire Department and a life member of the Kentland Volunteer Fire Department Station 33. He has an associate degree in fire science from Columbia Southern University.

FRANK RICCI is a member of the educational advisory board for Fire Engineering and FDIC International. He is a battalion chief and the drillmaster for the New Haven (CT) Fire Department. Ricci is also co-host of the BlogTalkRadio show “Politics & Tactics.” He is a contributing author to Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II and the lead author for the Tactical Perspectives DVD series. Ricci has been the lead consultant for several Yale studies and a past student live-in at Station 31 in Rockville, Maryland. He won a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case regarding fire service promotions.