Pier Fire in Boston: A Three-Day Operation

FIRE REPORT

Freezing temperatures, the inaccessible location of the fire, and the possibility of having to evacuate hundreds of hospital patients were some of the problems faced by Boston, MA, firefighters battling a six-alarm pier fire early this year.

A 3:37 a.m. telephone report of a small, outside fire at the rear of the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital summoned an engine, a ladder, and an acting district chief to the scene.

A column of black smoke was seen rising from the hospital parking lot where a 40-foot trailer (used as an office) was involved in fire. A portion of the adjacent pier serves as the parking lot for the 10-story hospital.

A full first alarm was dispatched. Within 50 minutes, the incident grew to a six-alarm fire.

The main body of fire was under the pier, involving hundreds of creosoted pilings with cap-logs and built-up wooden planks topped with asphalt paving.

Fire area layout

A three-story addition at the rear of the hospital rests on the pier’s concrete support columns. In addition to the trailer, the pier houses several small storage sheds and 10 sets of commuter rail lines that connect to a drawbridge trestle, which traverses the Charles River and a series of locks, built to keep the salt water of Boston Harbor separate from the fresh water of the Charles River. About 1,300 wood pilings support the approach to the trestle.

In addition to normal pier construction, there is the added weight of the gravel road bed, wood ties, and railroad tracks, made heavier by water and ice buildup.

A 15 to 20 mph northeast wind was closely monitored, since a shift in wind direction could have necessitated a rapid evacuation of the hospital, the most severe exposure. The hospital contained over 200 patients, most nonambulant.

Hospital personnel were advised to shut down any air intake systems to prevent smoke from being drawn into the building. Thirty ambulances were on standby and the adjacent helicopter pad was cleared in the event evacuation was necessary.

Another major concern was the hospital foundation. The possibility that wood pilings extended under the hospital had to be considered, since the pilings could allow the fire to burn through and emit smoke or fire directly into the hospital.

A series of holes were cut along the pier bordering the hospital so that cellar pipes could be used to cool the area and prevent fire from spreading in case such wood piling construction existed.

The hospital’s resident engineer arrived shortly after and assured fire officials that the structure was built on a solid foundation that did not rely on any support from the pier structure.

Fire spread and water supply

In addition to protecting the exposure, first arriving units hooked up to three hydrants located within 50 feet of the hospital and proceeded to darken down the fires in the structures on the pier. Additional hydrants were located several hundred feet from the incident, and relay operations from a high pressure hydrant helped supplement the needed water supply.

Flames leaping up over the edge of the pier indicated that the fire was extending southward.

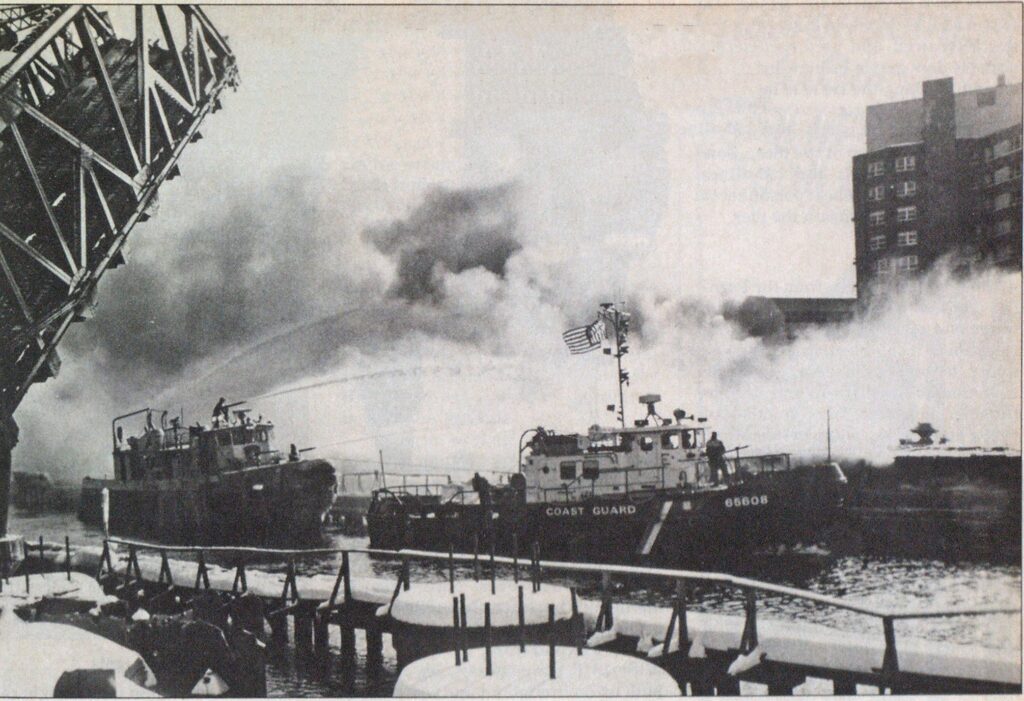

The Boston Fire Department Marine Unit was special called and a request for additional aid was sent to the Massachusetts Port Authority (which sent its 75-foot fireboat) and the U.S. Coast Guard (which provided six fireboats and a liaison team to coordinate communications and operations).

Fire also spread to the trestle. A frozen yard hydrant was found near the trestle, thawed, and used to supply a portable deck gun to extinguish the fire extending along the railroad ties.

Portable deluge guns and handlines were employed by land companies to attack the fire on top of the pier. Bow monitors, deck guns and handlines were operated by fireboat personnel to attack the fire underneath the pier.

Strategic factors

Although heavy smoke from the burning creosote was blowing toward the water and away from land operating companies, it cut the marine unit’s visibility to practically zero and made maneuverability difficult and uncomfortable. With the large number of heavy stream appliances in operation, the main concern of marine units was interfering with land operations and causing injuries by striking firefighters working on the pier.

To overcome this problem, two officers from the arson squad, which responds to all multiple alarms in Boston, were ordered to take up a position on the tenth floor of the hospital. Here, they could look down on the entire operation and radio the incident commander of the fire’s progress. It was reported that the fire was approximately 700 feet long by 300 feet deep.

Initially, marine units could only fight the fire at the southern end of the pier. Fireboat access to the northern side of the fire was blocked by the drawbridge trestle stuck in the down position. Opening the drawbridge would provide the necessary access and create a type of firebreak, preventing the fire from spreading to the other side of the canal.

The bridge would not open electrically, and it took time to accomplish this manually. However, once opened, marine units reached the northern end of the pier and were able to attack the fire on a second front.

With 13°F temperatures, ice quickly built up on firefighters and equipment, causing frequent falls but no serious injuries.

It was this steady buildup of ice that alerted the acting deputy chief to the weakening pier at the northern end. This area remained slushy, indicating high temperatures below. Shortly after firefighters were ordered off that section of the pier, it collapsed. A small portion of it fell into the water and extinguished itself. The rest cantilevered into various configurations depending on the degree of burn and the direction in which the supporting pilings collapsed. This added to the total extinguishing problem because it restricted hose line penetration.

Additional firefighting units

Scuba teams were also used to fight the fire. Divers entered the frigid waters with 1 1/2-inch lines to attack the pilings under the pier. They also investigated the conditions under the pier, reporting heavy charring and structural damage to an extent that it was unsafe for divers to operate. The scuba team reported a granite seawall running adjacent to the hospital. This wall served as a barrier to potential fire spread.

There was minimum truck work necessary at this incident. Ladder companies assisted in stretching lines and drilling holes in the pier through which cellar pipes and Bressnan rotating distributers were lowered to apply water to the structure below.

Boston’s high pressure fire hydrants are a unique system that was built in the 1920s. It is a separate system of water mains and hydrants installed in what was then the high value district following the Great Boston Fire of 1872, which destroyed a square mile of the business district.

Hydrants contain four 2 1/2-inch outlets, each independently gated. Static pressure in the system is about 60 pounds, but when a fire alarm is received in the high pressure area, pumps are put into operation, increasing pressure at the hydrant to 150 pounds. Two-and-a-half-inch lines can be stretched directly from the hydrant to the fire without using pumpers.

When the system was first installed, pressures could be increased to 300 pounds, but due to the age of mains and equipment, pressure today is rarely increased over 200 pounds. Originally, pressure was supplied by electrical or steam pumps. Recently, a new pumping station was built and the pumps are operated by a computer at the fire alarm station.

Fourth alarm units were used to assist marine personnel in operating deck guns, monitors, and handlines.

When a fifth alarm was ordered, mutual aid companies from surrounding cities moved into the Boston fire stations on a pre-arranged schedule.

Strategy and tactics

On the second day of the incident, officials from all involved agencies met to discuss solutions to bring the incident to a close.

The Transit Authority, who owns the pier, agreed to have the tracks cut on the southern section and then, using heavy equipment, knock down the burning pier for a distance of 20 feet beyond the seawall. This would isolate the burning pier to an island and assure that the fire would not extend to the pilings beyond the seawall.

The tactic worked, and the fire was declared under control the next day at 10:37 p.m., 67 hours after the first alarm was called in.

The fire department marine unit and an engine company continued to monitor the island fire for three days afterward.

The cause of the fire is still under investigation.