Protecting Buildings Against Terrorism

Although the probability of a terrorist attack is low, the cost of such an attack can be extremely high, as the incident at the World Trade Center (WTC) shows. In that case, the tally included lost rent for an extended period, relocation costs for tenants, costs of emergency around-the-clock structural repairs and debris removal, contending with numerous federal agencies, insurance claims, and lawsuits.

For management of commercial and public buildings/institutions, the risk-benefit analysis of terrorist attacks can pose a dilemma: W hat level of protection is appropriate for an event that is highly unlikely yet undeniably devastating? For these buildings, easy entry and egress, free circulation of pedestrians and vehicles, and an attractive and open environment are important for doing business. Security measures seem antithetical to these requirements and bring to mind a bunker or prison without windows surrounded by guards and walls. However, it is possible to work effective and economical security into the design of a modern-day commercial building in a manner that can minimize its intrusiveness. Although it is easier to implement a security system during the design stage of a new building, much can be done to renovate existing buildings to provide increased protection.

Security measures may reduce the chance that attack will occur simply by making a building an unappealing target. And they provide the added benefits of increasing the feelings of confidence and morale of those working there.

On the other hand, security measures that are too intrusive could decrease employee morale and business by making access to the building difficult. They also could cause a potential terrorist to escalate the level of attack to match the level of protection provided. The challenge, of course, is to provide an effective design that does not interfere with the fundamental functions of the building or attract too much attention.

Providing protection against a particularly devastating threat, such as a car-bomb attack, inherently provides protection against a wide range of other, lesser threats as well. However, there always will be some threats against which we will be unable to protect ourselves, such as that posed by a nuclear weapon. Also, depending on the current fashion among terrorists, such threats may change during the life of the building.

DEFINING THE THREAT

The first step in developing a balanced security design is to clearly define the target and the threat scenario. Depending on the building, the threat of most concern could be a car bomb in an underground parking garage, such as was the case at the WTC; a letter bomb in the mail room; or a briefcase bomb in the lobby or corridor. Typically, places that are easily accessible to the public are the most vulnerable. On the other hand, depending on a building’s function, the target could be the control center where the communication and emergency power lines of a facility converge. Clearly, these vital functions should not be placed within easy access of the public and should be in a protected environment.

When assessing the vulnerability of a building to terrorist attack, look for the weakest link in the building’s design, such as lack of controlled access or underground parking. What is the most accessible place where a terrorist could cause the greatest devastation? The lobby? The elevators? The toilets? Although a building cannot be made completely terroristproof or bombproof, there are ways to make it more difficult to execute certain types of attacks. By reducing the chances of the most devastating types of attack, such as a car-bomb attack, the threat can be reduced to a manageable level. For instance, prohibiting vans from parking in underground parking garages will limit the size of a potential explosion to that caused by the amount of explosives that can fit in a smaller vehicle. Weighing vehicles can further control the possible size of the weapon. The use of dogs to screen packages at airports is another example of how the size of potential explosions can be limited.

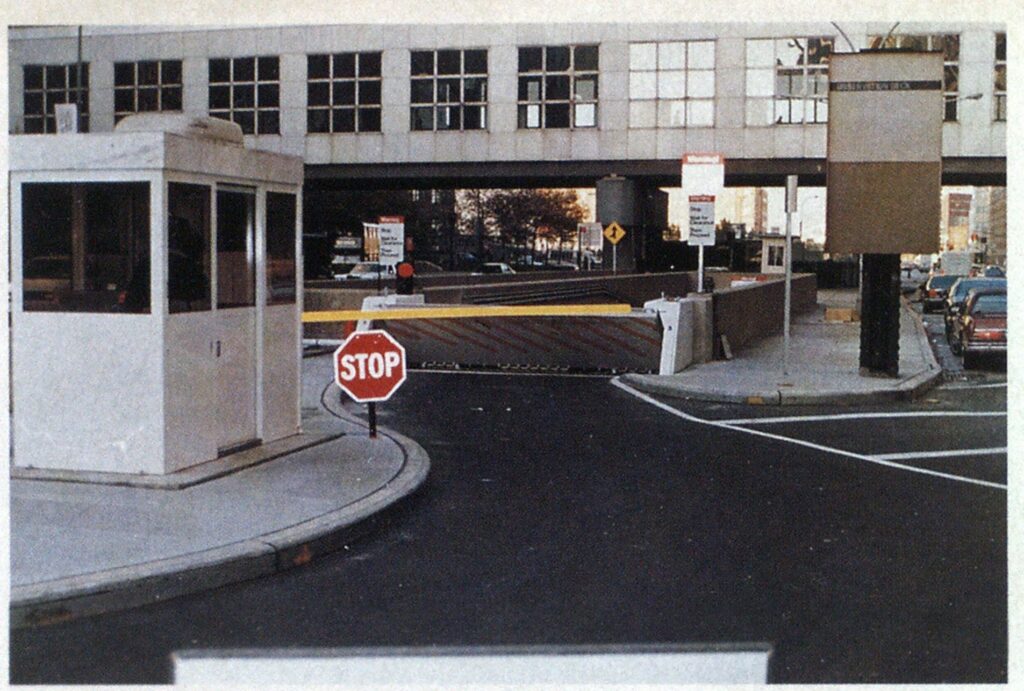

(Photos courtesy of Port Authority Risk Management.)

DESIGN OBJECTIVES

Once the threat is defined, you must establish your design objectives. Is your primary objective to protect people, functions, or the contents within the building? Typically, a combination must be considered. In a building such as the WTC, for instance, where thousands of people work and thousands more come and go during the course of the day, the primary objectives may be to save lives, reduce injuries, and facilitate evacuation and rescue. A secondaryobjective might be to regain function of the building as soon as possible after an attack, and a tertiary objective might be to reduce the damage to equipment and contents within the building. For another facility, such as a communications or power facility, where employees are few but the loss of function could affect millions, the primary objective may be to regain the function of the facility as soon as possible or at least to be able to shut down safely after an attack. For a storage facility, clearly the primaryfocus is to protect its contents.

One of the most effective ways of providing a balanced securitydesign is to provide several layers of protection between the attacker and the target. This “onion-skin” approach has several advantages. It deters an attacker by making the building a less appealing target. It physically distances the attacker from the target. It provides redundancy, so that if one line of defense fails, others are still in place. It provides delay time, enabling the mobilization of security forces to stop the attack before it occurs or mitigate its effects by causing it to occur under less than ideal conditions for the attacker.

If all else fails and an attack occurs despite all precautions, the last line of defense is walls, floors, and a framing system designed to resist the effects of a certain level of explosives. A blastresistant building still will require structural repairs after an attack, but the damaged area will be more localized than if no structural protection had been provided. If structural damage is limited, the volume of debris will be reduced, facilitating the rescue of persons trapped underneath the collapsed portions of the structure and expediting repairs.

(Photo courtesy of Port Authority Risk Management.)

OPERATIONAL AND PHYSICAL COUNTERMEASURES

Two types of countermeasures can be employed to contain an attack— operational and physical. Operational countermeasures are those that require human intervention. Physical countermeasures are architectural or structural devices built into the facility; they do not require human intervention to operate. An integral security design uses both types of countermeasures to provide protection to the building, requiring the integrated effort of several types of specialists— security specialists, planners, architects, and engineers.

One example of an operational countermeasure is stationing guards at a building’s access points to inspect packages and vehicles. Other examples include electronic devices such as closed-circuit surveillance TVs, intrusion-detection devices, metal detectors, and automated barricades, all of which need monitoring.

Physical countermeasures include strengthening the structural components discussed previously, but they also include providing architectural devices that help facilitate operational countermeasures and useful obstacles to keep a potential terrorist from easily accessing the intended target. Such obstacles include guard booths, inspection stations, perimeter fences or walls, bollards and planters on the sidewalk, and fountains or staircases at critical entry points—all of which work to keep vehicles from getting close to a building. Other physical countermeasures include providing off-site parking or arranging for the vital internal functions of the building to be placed away from easily accessible areas.

Because many injuries during carbomb attacks are caused by broken glass from windows, it is worthwhile to give some attention to a building’s window design. Smaller and fewer windows will reduce this risk; however. this approach is often unwelcome for commercial buildings. Another alternative is to use tempered glass or glass-clad polycarbonate windows, which are less apt to fail; w hen they do fail, it is in a less lethal manner. Windows specifically designed to resist the effects of an explosion are another alternative.

Buildings are “forever,” but memories of disasters are short-lived. Stories of the World Trade Center blast w ere front-page news around the world, only to be displaced within a week by the standoff in Texas between federal agents and David Koresh’s Branch Davidians. The initial shock in the w ake of an explosion caused by a few radicals is quickly forgotten. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence reopened a month after being gravely damaged by a car-bomb explosion; the St. Paul’s area of London was wiped clean of broken glass after an IRA bomb shattered windows across several square blocks; and the World Trade Center and Vista Hotel are now fully functioning, while undergoing continuing repairs and renovations. However, the underground parking garage is closed to transient visitors and may forever remain closed unless foolproof security measures can be devised to prevent the reoccurrence of last winter’s disaster. Unfortunately, w ith the passage of time there comes a return to openness and trust, a quality inherent to the human spirit. However, security and protection can be incorporated into buildings to act as a passive, nonintrusive shield to random terrorism.