|

| (1) A dewatering and ventilation operation at a high-rise office building in lower Manhattan. (Photos by Steven Spak unless otherwise noted.) |

BY RONALD R. SPADAFORA

As Hurricane Sandy made its way to the East Coast of the United States in October 2012, meteorologists called the storm unprecedented in terms of its potential for damage and fatalities. During hurricane season (an average of six hurricanes per year), New York City (NYC) is at its highest risk between August and October, when the North Atlantic water temperature is warm enough to sustain a hurricane.

Storm surge flooding often is the most deadly and damaging impact of a hurricane. Driving winds pushing the water very quickly cause it to form mounds higher than normal sea level. As the storm approaches land, the storm surge is pushed up the coastline and deep into inland areas, arriving as a rush of water. In addition, the storm surge can be capped by large waves.

Winds were predicted to increase from between 39 and 55 miles per hour (mph) Sunday evening (October 28) and from 40 to 60 mph Monday night into Tuesday. Gusts at higher elevations (buildings above eight stories and bridges, for example) were expected to reach 70 to 80 mph. The National Weather Service (NWS) warned that these high winds could last for 12 to 18 hours before returning to the 39- to 55-mph range. Additionally, since anticipated storm arrival coincided with high tides, more water would be available to be affected by the hurricane. The water would be pushed toward the coastline, creating a large mass. This additional water would accumulate in bays and harbors for a substantial period of time.

While I worked as the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) citywide tour commander on Saturday, October 27, NWS information obtained through a Coastal Storm Steering Committee teleconference attended by FDNY personnel stated that the storm was once again being classified as a Category 1 hurricane. Further information revealed that the area of landfall was still uncertain, although this information was not deemed important since the storm was so large that the entire metropolitan area would be affected regardless of the exact landfall location.

PREPARATION

Throughout the next 48 hours, I (as the chief of logistics) would be confronted with a multitude of activities pertaining to FDNY preparation. A list of some of these issues included the following:

- Ensuring that FDNY liaison staffing was in place at the NYC Office of Emergency Management (OEM).

- Coordinating with OEM the opening and setting up of shelters in all five boroughs for evacuees from areas threatened by storm surge.

- Providing personnel in support of the voluntary homebound (civilians in evacuation zones who needed assistance leaving their residences) evacuation effort.

- Reviewing Incident Management Team (IMT) activities listed in the Incident Action Plan (IAP) with IMT members to avoid duplication of services.

- Exchanging information with the Fire Department Operation Center (FDOC).

- Acquiring fuel locations (gasoline for vehicles, small hand tools, and generators) at New York Police Department (NYPD) precincts.

- Prioritizing usage of our dewatering pump resources.

- Charting reserve apparatus locations.

- Visiting firehouses to evaluate storm preparation efforts first hand.

- Providing situational awareness messages to all members by voice alarm (public address system); teleprinter (electromechanical typewriter); and the DiamondPlate, the in-house Web portal (see “FDNY DiamondPlate,” page 30).

This article provides an overview of FDNY’s organizational preplanning and preparation procedures for large-scale weather events, specifically hurricanes. It is important to have a disaster plan in place to act as a template for successful protocols and actions. It also guides training. Practicing and understanding firefighting techniques and hazards unique to a given incident are critical for successful operations.

ANTICIPATION

Depending on the strength of a storm, fire department units must anticipate increased call volume, civilian evacuations, restricted access to parts of their response area, and possible evacuation of quarters. Other concerns include the following:

- The need to rescue civilians who require immediate medical attention.

- Flooded conditions hindering emergency response.

- Buildings that have been undermined and are in danger of collapse.

- Damaged/weakened building facades, marquees, cornices, cell phone sites, signs, and so on.

- The loss of electric power of a large area affecting high-rise buildings, hospitals, critical infrastructure, and occupied elevators.

- Utility emergencies (natural gas leaks, transformers, electrical arcing/short-circuiting) and subsequent fires caused by subgrade flooding.

- The hidden electrocution hazard presented by fallen power lines.

- Fallen trees blocking street access.

- Gridlocked traffic conditions.

- The contamination of personnel, apparatus, personal protective equipment, tools, and equipment resulting from operating in flooded areas.

- Civil unrest (looting, civil disobedience, and insurance fraud fires).

|

| (2) Medical responses during the first few days of the hurricane topped 21,000! |

NYC EVACUATION ZONES

NYC’s hurricane contingency plans are based on three evacuation zones (A, B, and C). The zones relate to varying threat levels of coastal flooding resulting from storm surge. NYC residents use the Hurricane Evacuation Zone Finder at NYC.gov or the 311 system to gain information concerning what hurricane evacuation zone they live and work in. This is a great way for NYC citizens to prepare for the possibility of a hurricane evacuation. They are then able to plan their destination and travel routes ahead of time.

- Zone A. People in this zone face the highest risk of flooding from a hurricane’s storm surge. It includes all low-lying coastal areas as well as other areas that can experience storm surge from any hurricane that makes landfall in the vicinity of NYC.

- Zone B. This zone may experience storm surge flooding from a Category 2 or higher category hurricane.

- Zone C. This zone may experience storm surge flooding from a Category 3 or 4 hurricane making landfall south of NYC.

Source: NYC Office of Emergency Management. “NYC Hazards: Hurricane Evacuation Zones,” 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2013 at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/oem/html/hazards/storms_evaczones.shtml.

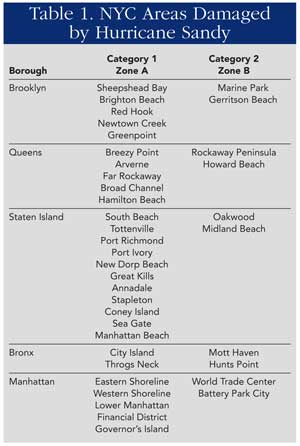

NYC AREAS OF DEVASTATION

FDNY procedures for hurricanes and severe storms anticipate critical locations where large areas of flood damage caused by storm surge are expected to be found. These critical areas, demarcated by borough commands, are based on NYC hurricane evacuation zones and the storm’s intensity. Some of the geographic locations (neighborhoods) that sustained extensive damage from Hurricane Sandy are denoted in Table 1.

PREPLANNING

Preplanning for hurricane and severe storm emergencies must be ongoing throughout the year for the outcome of operations to be successful. All levels of command must be involved. The FDNY maintains a continual liaison with other city, state, federal, and nongovernmental agencies to ensure quality preplanning operations. Among these organizations are the U.S. Weather Bureau, OEM, New York Police Department, U.S. Department of Transportation, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, utility companies (Con Edison, National Grid, LIPA), Regional Emergency Medical Services Council, Department of Environmental Protection, National Guard, U.S. Coast Guard, New York State Department of Health, Department of Parks and Recreation, Transit Authority, National Park Services, Sanitation Department, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and Federal Emergency Management Agency, to name just a few.

At the chief of operations level, schedules and assignments for staff chiefs, FDOC personnel, and OEM liaison officers are updated during storm emergencies. Procedures for increasing the staffing of units (five firefighter engine companies, for example) and the activation and staffing of reserve (both engine and ladder) apparatus and special units are put in place. Emergency supplies (gasoline, fuel oil) from contracted vendors as well as other agencies are coordinated to ensure availability.

Borough fire commands ensure that division, battalion, and unit commanders have designated a storm operations coordinator. The list of coordinators is updated on May 1 of each year and as needed. The Borough Command Hurricane Checklist includes all of the following preplanning information:

- Identify storm operations coordinators and their alternates.

- Review the current IAP, if generated, pertaining to hurricane relocations, homebound evacuations, and activation of special units. Note: Specialized vehicles and watercraft may be assembled during major storms, power blackouts, and complex incidents. When staffed, these units respond to multiple incidents necessitating a single-unit response to address the numerous, rapidly occurring hazardous conditions that accompany weather-related incidents and disruption of services. The identified responses may include, but are not limited to, trees/wires down, stalled elevators, and flooding conditions.

Special units include the following:

—Rapid Response Vehicle (RRV): a box-type truck equipped with specialized tools and equipment for supporting hazardous materials and technical rescue operations. The RRV, staffed with specially trained firefighters, can also operate independently. Each RRV has two chain saws, making these units ideal for tree-removal operations.

—Brush Fire Unit (BFU): a four-wheel-drive, all-terrain vehicle used to reach hilly, remote, and marshy areas to extinguish fires involving weeds, grass, and other vegetation. Along with regular firefighting equipment, a BFU carries its own water, rakes, shovels, and backpack extinguishers.

—Swift Boat: a shallow-draft, ruggedized, PVC inflatable drift boat brought to flooded areas by vehicle. These boats have proved to be invaluable in storm surge and flooded areas; they enabled firefighters to rescue and evacuate hundreds of endangered residents.

- Consult Continuity of Operations Plan (COOP) from headquarters.

- Update the hurricane contact list to determine the availability of resources and services.

- Confer with emergency medical services (EMS) divisions.

- Establish staffing procedures.

- Contact Fleet Maintenance regarding emergency mechanical and tire repair.

- Arrange for reception areas identified by divisions. Note: A reception area is a location separate from a staging area, where resources report in for processing and out-processing. A reception area provides accountability, security, situational/safety awareness, and the distribution of IAPs, supplies, and equipment.

- Encourage members of their command to prepare their homes and families for a possible hurricane.

Division command hurricane preplanning is similar to the boroughs’ plans, with additional requirements. Division storm operations coordinators (as do battalion and company storm operations coordinators) initiate surveys of occupancies with preincident guidelines (PGs) that may require special operating procedures during storm emergencies. Firehouses are identified as possible staging area sites. Necessary equipment and supplies [food, water, cots, batteries, self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) cylinders, saw blades, portable radios, and so on] are procured for these locations.

Additionally, divisions must determine dispersal sites, locations other than firehouses from where flooded companies can be dispatched during a storm and where extra units can be positioned during emergencies. Designated NYC evacuation shelters are inspected for fire safety before the storm season. EMS division commanders are consulted for assistance in coordinating the preplanning of activities.

Battalions visit all units under their command to determine their readiness, the serviceability of their apparatus/equipment, examine staging area preparations and supplies, and submit requisitions as needed. At the battalion level, drills are conducted with the units to ensure members’ readiness and familiarity with storm procedures.

Company commanders also have important preplanning responsibilities. They must determine if their firehouses will flood under storm conditions or if their facilities can be used to host relocated companies and evaluate the condition and operational status of emergency generators and hookup connections, if any. Their units are required to survey institutional occupancies (hospitals, nursing homes, and correctional facilities) and keep pertinent information current and to identify fire hydrants in their administrative district that are likely to be submerged during a storm. Units have storm maps, provided by the FDNY Geographical Information Systems (GIS) unit, prominently displayed inside their quarters. They must check the operational status of generators and dewatering pumps and take an inventory of tools, supplies, and equipment.

OPERATIONAL PHASES

When it is anticipated that a severe storm is predicted to strike NYC, the FDNY operational plan is divided into two phases: A, the Activation Phase, and B, the Implementation Phase. The chief of department or the chief of operations determines which phase is to be initiated, terminated, or changed.

|

| (3) Storm surge waters flow into NYC through the “New York Bight.” (Image courtesy of the NYC Office of Emergency Management.) |

Phase A

It is implemented when weather forecasters predict that a severe storm is approaching NYC. It initiates and encompasses preliminary activities and planning by boroughs, divisions, battalions, and field units—as noted above, in preparation for the incident. Phase A was instituted on October 25, 2012, in anticipation of Hurricane Sandy’s arrival.

Phase B

It is instituted when actual emergency conditions are present or are imminent and it has become necessary to implement special activities. It is not necessary that Phase A be instituted prior to Phase B. If a situation develops necessitating forthwith emergency measures, Phase B is activated immediately while the activities involved in Phase A are automatically implemented.

Phase B operational activities during Hurricane Sandy included increased staffing for FDOC, borough and division fire commands, and field units; staffing reserve apparatus and special units; and activating the FDNY IMT. Various FDNY support and resource bureaus were also bolstered during Phase B. Tow trucks, four-wheel-drive vehicles, and mobile heavy equipment were staffed. Fuel was ordered and delivered to firehouses and EMS stations. Phase B was instituted on October 28.

TRAINING

Division chiefs, battalion chiefs, and company commanders address preplanning for storm operations by line units during multiunit and company drills regularly. Training and discussion topics include the following:

INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEM (ICS) AND INCIDENT MANAGEMENT TEAM (IMT)

In December 2001, the FDNY reached out to the United States Navy (Naval War College in Rhode Island) for help in analyzing its leadership and management capabilities. Fifty senior FDNY members participated in a two-day training session (War Games) at the U. S. Merchant Marine Academy at King’s Point on Long Island. The exercise was designed to critically examine FDNY leadership/management as well as command and control issues. Postgame evaluation recommendations saw the need for the FDNY to dedicate resources and funding to develop new ways to deal with large-scale and complex operations.

Following this training, in February 2002, the FDNY asked McKinsey and Company, the world’s largest management consulting firm, to evaluate its performance during the 9/11 rescue and recovery operation. On August 19, 2002, the McKinsey report Increasing FDNY’s Preparedness was released. Recommendations commenting on the FDNY’s use of the incident command system (ICS)1 included expanding the use of ICS to provide a foundation for responding to and managing any type of emergency as well as creating an IMT consisting of specialized, highly trained personnel who use ICS principles to manage large and complex incidents.

McKinsey report findings led the FDNY to seek a Cooperative Agreement with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) in January 2003. The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) secured training for FDNY personnel through the USDA’s Forest Service branch to develop IMT capabilities. The FDNY agreed to receive ICS training and, at the discretion of the FDNY, provide trained and certified personnel to assist in responding to complex or long-duration incidents outside of NYC. On request and with the approval of the chief of department, this IMT may be deployed anywhere in the country. The MOU, therefore, provides additional resources for Homeland Security within NYC as well as nationally. The U.S. Forest Service Northeastern Area Command recognizes the FDNY IMT as the region’s Type 2 IMT.2

On Sunday, October 28, the FDNY activated its IMT. All storm-related issues, questions, and inquiries as indicated in the IAP were to be directed to the IMT. The following objectives were established for the IMT:

- To provide for the safety of the public and FDNY members.

- To provide for fire and life safety functions according to the Citywide Incident Management System (CIMS).3

- To ensure borough resource capability and flexibility to provide fire and life safety service in the event of isolation or bridge closures.

- To ensure the ability to support fire and EMS life safety operations in flood prone areas.

- To develop a dispatch and communications plan for reserve and special units placed in service as a result of the hurricane.

- Effective use of BFUs to support EMS operations.

On December 27, 39 members of the Lone Star State (TX) IMT transitioned with the FDNY IMT and accepted responsibility for overseeing a needs assessment and commodity distribution system put in place after Hurricane Sandy hit NYC in late October.

INCIDENT ACTION PLANNING

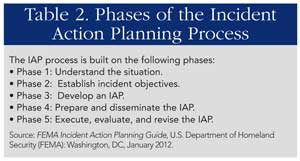

Because ICS is the basis for managing incident activities, all IMTs use the ICS incident action planning process, which can bring order to a chaotic incident and enables incident management personnel to address complex problems that may seem overwhelming. Disciplined application of the process produces beneficial effects for incidents of any size or scope. Most importantly, it requires collaboration and participation among all incident management leaders from across the whole community.

Incident action planning is a set of integrated activities established for each operational period that provides a structure to incident management (Table 2). Incident leaders must ensure that the plan meets the needs of the incident. Incident action planning is an operational activity and must either direct or support operations. An IAP helps to ensure that activities are conducted in support of incident objectives. A well-conceived, complete IAP facilitates successful incident operations and provides a basis for evaluating performance. The IAP identifies incident objectives and provides essential information regarding incident organization, resource allocation, work assignments, safety, and weather.

WIRELESS PRIORITY SERVICE

The Federal Communications Commission issued a Report and Order on July 13, 2000, allowing cellular providers to offer wireless priority services to first responder personnel at the federal, state, and local levels to help meet the national security and emergency preparedness (NS/EP) communication needs of our country. This ruling established the regulatory, administrative, and operational framework that enables cellular service companies to provide Wireless Priority Service (WPS) to first responders.

|

| (4) Down pole-mounted transformers, live electrical wires, and massive tree stumps and branches posed electrocution, hazardous material, and response dangers. (5) Flood conditions can cause havoc to mechanical and electrical components on first responder vehicles. |

|

WPS is a priority calling capability for first responders that greatly increases the probability of call completion using cellular phones, even during situations of high call volume or damage to telecommunications facilities in the course of an NS/EP incident. WPS and its companion priority service call for everyday telephone equipment, the Government Emergency Telecommunications Service (GETS), are requested through a secure online system.

Federal, state, local, tribal government, and critical infrastructure personnel are eligible for WPS. NS/EP organizational criteria for WPS eligibility are based on five categories established by DHS’s Office of the Manager, National Communications System. To ensure communications for senior leadership, these categories are also used to assign levels of priority when WPS calls are placed in an originating radio channel queue. All WPS and GETS calls have the same priority across the network and in the terminating radio channel queue. The categories are as follows:

- Executive Leadership and Policy Makers

- Disaster Response/Military Command and Control

- Public Health, Safety and Law Enforcement Command

- Public Services/Utilities and Public Welfare

- Disaster Recovery

Major weather events can disrupt communication channels, leading to congestion on the public telephone network. During such an emergency, first responders and government officials compete with the public for the same overtaxed communication resources. WPS/GETS cards issued to NS/EP personnel facilitate phone calls getting through when mainstream and emergency telecommunications systems fail. The WPS/GETS program is designed to provide 90 percent call completion rates when call volume is eight times greater than normal capacity. All FDNY staff chiefs and key personnel are issued WPS/GETS cards.

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

In March 2009, DHS provided grant funding (Urban Area Special Initiative) to the FDNY. This support was designed to enhance knowledge in three major areas: Operational Readiness, Situational Awareness, and Disaster/Terrorism Preparedness. The development of a Web-based Training and Awareness Resource (Kiosk Project) was the result (see “FDNY DiamondPlate,” page 30). Through a Web portal, called the DiamondPlate, centralized information intended to improve the professional development of FDNY members became accessible through computer work stations in every firehouse and the EMS base of the department.

|

| (6) The construction crane dangling in the wind on W. 57th Street in Midtown Manhattan. (Photo by author.) |

Coverage of Hurricane Sandy through DiamondPlate started on October 25, when information was posted concerning a “perfect storm” making its way up the U.S. East Coast. On October 26, an essential situational awareness feature of DiamondPlate was activated. The FDOC issued an ALERT providing the latest weather conditions and planning procedures being conducted to prepare for the upcoming hurricane event. The entire FDNY workforce was privy to real-time information, allowing them to better understand the hazards involved and requirements necessary for preparation. The continuing coverage of Hurricane Sandy can be broken down into four categories: Prestorm, Storm Operations, PostStorm, and Recovery.

Prestorm

Components include the following: weather conditions, hurricane location and movement, hurricane preparedness procedures, water rescue tools, equipment, operational procedures, and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) storm surge sensor installations. The USGS, a scientific agency of the U.S. government, deployed numerous storm surge sensors along the waterways of NYC. In the past, these sensors had been mistaken for improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Storm Operations

Components include the following: weather updates, chief of safety messages (storm operations-related emergencies, flood operations, and down trees and wires), apparatus response, utility and infrastructure issues, and dangerous conditions (collapse, structural instability, and freestanding walls).

Poststorm

Components include the following: photo gallery (Hurricane Sandy aftermath), chief of safety message (improper and dangerous use of generators), tree-removal operations and portable dewatering pump operations and recap of FDNY operations, portable dewatering pump operations and recap of FDNY operations.

Recovery

Components include the following: floodwater health hazard warnings, transportation/storage of flammable gas and fuels, illegal use of fuels and fuel hoarding,4 hurricane assistance for FDNY members, nor’easter information,5 mold contamination, and recap of NYC recovering from Sandy’s surge.

ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Preplanning and preparation empowered first responder actions. Initial IMT-coordinated search and rescue operations during the onset of Hurricane Sandy were facilitated by the National Guard; urban search and rescue (US&R) task forces from Maryland, Virginia, and Massachusetts; as well as the Broome County (NY) Swift Water Task Force. Hundreds of civilians citywide were rescued from the storm surge by watercraft. Vast numbers were evacuated to safety. One single incident alone, a crane failure in midtown Manhattan, necessitated the evacuation of thousands over a several-block area. Dozens of fires resulting from the storm surge were extinguished including one sixth alarm (more than 100 homes destroyed), one fourth alarm, one third alarm, and eight second alarms. Medical responses from October 28 through November 1 numbered more than 21,000.

Dewatering Operations

In addition to search and rescue, FDNY personnel were tasked with dewatering operations, deenergized elevator emergencies, and tree/debris removal. Dewatering operations encompassed all types of venues, including high-rise office buildings, institutional and commercial establishments, road and rail tunnels, subways, utility infrastructure, multiple dwellings, and private homes. Nearly one million NYC residents lost electrical service. Building occupants unfortunate enough to be inside elevators at the time of power loss were trapped and in dire need of rescue. Tree/debris removal entailed clearing building entranceways and roadways to allow access for occupants and emergency vehicles.

Fires and floods pose significant threats to populations, structures, and infrastructure. Knowing the potential risks and dangers, anticipating them, and planning and preparing for operations before, during, and after a disaster can mean the difference between mass casualties/total property loss and greatly minimizing life loss/resulting damage. Although disasters are generally unpredictable, important steps can be taken before a disaster occurs to reduce their impact. Preplanning and preparation are essential key factors leading to success for first responders as well as emergency management personnel.

Special thanks to the Big Easy firefighters who traveled to NYC to repay a debt of gratitude. Their help (dewatering, cleaning, and rebuilding storm-damaged homes) in the NYC recovery effort mirrored the work performed by FDNY members seven years ago in New Orleans during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Thanks also to the New Orleans District Office of the Army Corps of Engineers, which provided 25 six-inch and eight-inch dewatering pumps to NYC to assist in the removal of floodwater from the subway system and transportation tunnels.

Endnotes

1. The ICS was developed as a cooperative effort involving all agencies with firefighting responsibilities in California after the disastrous 1970 wildland fires that occurred in the southern portion of the state. ICS assists governmental agencies in managing resources at emergency incidents. It provides an organizational staff that establishes command and control. ICS also addresses operational, planning, logistics, and finance issues relating to large and complex events. All federal and state emergency response agencies are now mandated to operate in accordance with ICS.

2. A Type 2 IMT is a federal- or state-certified team, typically used at the national and state levels. Its members have less training, staffing, and experience than a Type 1 IMT, and the team is normally used for smaller-scale national or state incidents. There are 35 Type 2 IMTs in the United States. They operate through interagency cooperation of federal, state, and local land and emergency management agencies. Type 1 IMTs are also federal- or state-certified and are used at the national/state level. They are the most robust IMTs. Sixteen Type 1 IMTs exist. Type 1 IMTs also operate through interagency cooperation of federal, state, and local land and emergency management agencies. IMTs provide an organized high standard of efficiency, safety, and experience in the management of complex, large-scale, and long-duration incidents.

3. On May 14, 2004, NYC Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and OEM announced the City’s adoption of CIMS as NYC’s program for responding to emergencies, recovering from emergencies, and for managing planned events. On April 11, 2005, Mayor Bloomberg signed an executive order formally mandating its implementation for personnel involved in NYC incident command and emergency response. CIMS establishes roles and responsibilities and designates authority for city, state, and other government entities, and non-profit and private-sector organizations performing and supporting emergency response. CIMS is NYC’s implementation of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). It was developed to address NYC’s unique incident management requirements. It is in full compliance with NIMS, thereby ensuring compatibility with incident command systems in use in other states and federal agencies.

4. FDNY fire marshals arrested a chef at an East Side restaurant for hoarding gasoline in soy sauce buckets. The fuel caught fire as it was being transported by a worker from the cellar of the occupancy to the kitchen. Three of his co-workers were seriously burned. In another incident, the New York Police Department arrested a man accused of filling up 30 five-gallon Home Depot buckets with gasoline.

5. Nine days after the devastating impact of Hurricane Sandy, a nor’easter slammed into the NYC area. The storm brought wet snow, sleet, rain, and wind gusts that topped 50 mph. Thousands of Con Edison customers had their electrical power knocked out; some had just gotten it back.

Bibliography

California Hospital Association, “GETS/WPS,” 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2013 from: http://www.calhospitalprepare.org/getswps.

Fire Department of New York. All Unit Circular 159, “Hurricane and Severe Storm Emergencies,” October 6, 2009.

Fire Department of New York. All Unit Circular 159, Addendum 2,” Hurricane Evacuation Maps,” October 6, 2009.

Fire Department of New York. All Unit Circular 159, Addendum 3,” Hurricane Binder Layout and Checklists,” October 6, 2009.

Fire Department of New York. Firefighting Procedures, Collapse Operations, Addendum 2 “Search Assessment Marking System,” June 7, 2007.

Fire Department of New York. ICS Manual, Chapter 7,” Incident Management Teams,” March 23, 2006.

Fire Department of New York. Incident Action Plan (Incident Name: Hurricane Sandy Incident) Operational Period Date/Times: 0900 10/29/12 to 0900 10/30/12.

McKinsey & Company, Inc. McKinsey Report: Increasing FDNY’s Preparedness. Fire Department of New York: New York, August 19, 2002.

NYC Office of Emergency Management. “Emergency Response: Citywide Incident Management System,” 2012.Retrieved January 3, 2013 at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/oem/html/about/about_cims.shtml.

NYC Office of Emergency Management. “NYC Hazards: Hurricane Evacuation Zones,” 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2013 at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/oem/html/hazards/storms_evaczones.shtml.

Spadafora, Ronald R. “Origin and Development of FDNY Incident Management Teams-Part 1,” WNYF, 4th issue, 2003, pages 16-17.

Spadafora, Ronald R. “Origin and Development of FDNY Incident Management Teams-Part 2, Shadow Training,” WNYF, 4th issue, 2004, pages 14-17.

Spadafora, Ronald R. and Thomas Dowling. “The FDNY Kiosk Project—A Web-Based Training and Situational Awareness Tool,” WNYF, 1st Issue, 2012, pages 29-30.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “Wireless Priority Service,” Retrieved January 3, 2013 at: http://wps.ncs.gov/program_info.html.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (Federal Emergency Management Agency). FEMA Incident Action Planning Guide. U.S. Department of Homeland Security (FEMA): Washington, DC, Jan. 2012.

● RONALD R. SPADAFORA is an assistant chief and a 34-year veteran in the Fire Department of New York (FDNY). He is the chief of logistics in the Bureau of Operations. He has written dozens of articles in periodicals such as WNYF, Fire Engineering, Size-Up, and the American Journal of Industrial Medicine. His most recent book, Sustainable Green Design and Firefighting—a Fire Chief’s Perspective, was published in 2012. He is an adjunct instructor at Metropolitan College of New York (Emergency and Disaster Management—MPA program) and at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (fire science—BS/BA program).

FDNY DiamondPlate

BY RONALD R. SPADAFORA AND THOMAS DOWLING

After the attack of September 11, 2001, the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) realized the immense loss of experience that had just occurred. This hard-earned expertise could not be easily replaced. DiamondPlate, a Web-based training and situational awareness tool, was born out of a need to preserve the collective knowledge that the FDNY builds on every day.

In March 2009, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) provided grant funding (Urban Area Special Initiative) to the FDNY. The initial project budget was more than $3 million for an 18-month term. The success of this initiative hinged on proper planning. The first step was to draw up a Project Charter. This document included the department’s core competencies and the requirement—to deliver a broad range of information to the members in the field in a quick and efficient manner. Sponsorship took the form of a two-pronged approach led by the Bureau of Operations and the Bureau of Technology Development & Systems (BTDS).

In February 2011, a Governance Committee was formed to improve oversight of the project, review goals/scope, and clarify key roles and responsibilities. New ideas were developed, with emphasis on producing quality videos as well as archiving existing film to support text. Editorializing YouTube videos with internally developed content was another initiative taken and has proved to be an effective and popular learning tool.

FDNY members were identified early as overseers, providers, and consumers of this information. Bureau heads identified experienced personnel within their respective commands who could formalize thought into content. These individuals became the “writers” or subject matter experts. Once the content was developed, it had to be reviewed and authorized for distribution. To fast-track this process, bureau heads also selected chief officers to review and disseminate the information. These roles were identified as the “publishers.” Representatives of participating bureaus meet regularly to discuss timely topics and address workflow concerns.

Charter participants came from diverse areas of the FDNY:

- Office of the Fire Commissioner

- Office of Medical Affairs

- Bureau of Health Services

- Bureau of Operations

- Bureau of Emergency Medical Services (EMS)

- Bureau of Training

- Bureau of Safety

- Center for Terrorism & Disaster Preparedness (CTDP)

- Bureau of Fire Investigation

- Mand Library

As part of the workflow creation, a software tool (Adobe® Contribute®) was introduced to writers and publishers. This provided a browser-based publishing environment that fit the needs of the project and facilitated the editorial process. A training curriculum was developed around this application. Once established, bureau-identified personnel were trained on the software. The training allowed the writers and publishers to use extensive archival material already existing within the FDNY, quickly turning it into topical Web content. Additionally, a large amount of applicable information on the Internet was also leveraged, placing it into the context of the FDNY’s needs.

Although creating operational content took the lead, developing an effective informational highway was essential. Facilities management personnel provisioned the data and electrical cabling; BTDS handled the networking equipment and computer workstations. Additionally, to support a reliable system, telecommunications and infrastructure build-outs were implemented. Broadband connectivity was expanded throughout the FDNY.

Timely, accurate, and insightful distribution of knowledge required communication with members at their work locations. This started at the field level during site surveys of firehouses and stations. Uniformed officers from the Bureaus of Operations and EMS were instructed to converse with company and station officers as well as subordinates regarding ideal kiosk workstation equipment placement. The workstations are provisioned with both FDNY Intranet and Internet access, as well as a local printer. The goal was to select an area readily accessible and large enough where all members could gather and learn. In most cases, the kitchen was deemed most appropriate.

DiamondPlate was launched on May 2, 2011. It began with the fire commissioner’s introduction video, which included opening remarks from the chief of department, chief of operations, and chief of EMS. Home Page stories and video clips encompassed a wide array of current events. Content presented consisted of “Breaking News” regarding President Barack Obama’s announcement of the death of Osama Bin Laden. The Bureau of Operations featured a review of a recent third-alarm fire in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. The Bureau of Training highlighted motor vehicle accident operational and safety issues. The CTDP showcased the vehicle-borne improvised explosive device incident handled successfully by first responding FDNY units at Times Square. Building collapse awareness took center stage for the Bureau of Safety; the Bureau of EMS introduced its new fleet of ambulances.

Since the successful start-up of DiamondPlate, thousands of new articles and videos have been published. Another key component of DiamondPlate involves member interaction. Article comments and content recommendations have been incorporated throughout the Web site to maintain the value of field input. This feature allows all department members to lend their voice and help shape future learning for decades to come.

DiamondPlate has been officially recognized for excellence twice. On November 15, 2012, the project workgroup was presented with the FDNY Administration Medal for exemplary service to the department in the development of an agency-wide Intranet information system. On February 6, 2013, the DiamondPlate team was presented with the Best Application Serving an Agency’s Business Needs by the Department of Information Technology & Telecommunications.

RONALD R. SPADAFORA is an assistant chief and a 34-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York. He was co-sponsor for the DiamondPlate project.

THOMAS DOWLING is the director of the Bureau of Technology Development & Systems and a 32-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York. He was co-sponsor for the DiamondPlate project.

Fire Engineering Archives