|

| (1-6) These photos show the main boom blown over the cab and main frame of a 1,000-foot-tall tower crane. (Photos by Aron Buch, Rescue 1.) |

BY JOHN SUDNIK

At 1433 hours on October 29, 2012, Fire Department of New York (FDNY) units responded to a reported crane collapse on W. 57th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. On arrival, units found that a section of a construction crane’s boom was hanging precariously at the 75th-floor level, obviously the result of the near-hurricane-force winds.

SIZE-UP

Emergency operations at incidents where either a structure has “collapsed” or is “in imminent danger of collapsing” are generally similar. Since the imminent collapse can, and sometimes will, result in a collapse or structure failure, the strategies, tactics, and safety precautions for both scenarios are standardized.

|

| 2 |

A major structural collapse will normally create numerous hazardous conditions that responding fire department units must recognize and handle. The potential hazards to fire department members and civilians alike include, but are not limited to, the following: the structural instability of adjoining structures; ruptured water, high-pressure steam, and natural gas mains; down electrical wires; and respiratory exposure to dust and asbestos. In imminent collapse situations or in instances where collapse has already occurred, operating units must consider all such hazards in their size-up while simultaneously immediately addressing the imminent threat to life. Confronted with near hurricane-force winds, the first-arriving FDNY chief and company officers quickly determined that the hanging boom section of the crane at the 75th-floor level was in danger of imminent collapse, which would create significant exposure to several life-threatening hazards.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

Establishing the initial collapse danger zone is the most essential safety precaution at a collapse incident. During the initial stages of an operation, access to the site must be immediately controlled to reduce the risk of exposure for responders and civilians to the potential hazards. Barriers are erected to keep civilians out of the danger zone and also to prohibit them from interfering with emergency operations. Equally as important, the IC must provide for personnel accountability by establishing and maintaining control points and granting access only to authorized personnel and resources.

|

| 3 |

FDNY units accomplished these tasks by using the public address feature on the apparatus to quickly evacuate W. 57th Street in the area immediately below the hanging boom and apparatus along with yellow barrier tape to control access from W. 57th Street at 6th and 7th Avenues. When the danger zone was eventually expanded to include W. 56th and W. 58th Streets, the IC requested the NYPD resources to secure the entire perimeter.

Much of the inherent danger at collapse incidents is often attributed to factors responding fire department units find difficult to predict, identify, or control. Since it is virtually impossible to determine the exact point of additional failure of a compromised structure, life safety operations are guided by an ongoing risk/benefit analysis. The evacuation of W. 57 Street directly below the hanging boom was initially the highest priority, and operations in that extremely dangerous area were warranted given the significant potential for loss of life.

The next incident objective was to gain access to, and begin evacuation of, exposures from areas of relative safety. The IC assessed the potential damage resulting from boom failure, and occupants were removed from the most exposed buildings first.

Although the hazard potential from utilities is always a concern at collapse incidents, the extent of the hazard is not always readily apparent. Having emergency crews from all involved utility companies present at the incident command post (ICP) is necessary to accurately assess and mitigate the hazard potential. Con Ed representatives on the scene briefed the IC early in the incident about the “catastrophic” secondary events that would likely occur as a result of a falling boom’s piercing the high-pressure steam and high-pressure natural gas mains running under W. 57th Street. Since a breach of utility lines would endanger occupants and FDNY members in and around the nearby buildings, mitigation of these hazards now became a primary incident objective. FDNY members are not trained or equipped to isolate and purge high-pressure steam and gas mains. Only qualified utility company personnel must handle these tasks.

|

| 4 |

Since these two separate mitigation operations needed to be performed inside the collapse zone, FDNY units were assigned to assist Con Ed personnel and provide for their safety and accountability.

Incident Command

In addition to performing an initial size-up of conditions and addressing any immediate safety concerns, the IC must establish command and take control of the collapse incident. According to the NYC Citywide Incident Management System (CIMS), a structural collapse is considered a single command event (as opposed to Unified Command) and the FDNY ranking officer is designated as the IC. One of the initial considerations for the IC at any incident is to promptly establish the ICP. It should be in the immediate vicinity, but outside of, the collapse danger zone. If inclement weather or other factors affect the efficient operation of the command element, it may be advantageous to relocate the ICP to the inside of a building. Regardless of the location, the area must be large enough to accommodate representatives from other agencies. Obviously, the heavy wind and rain from the storm created adverse conditions, and the ICP was promptly moved to the inside of a retail store on the corner of W. 57th Street and 7th Avenue.

As in any type of large-scale emergency operation, clear and concise interunit communications on the portable radio tactical channel are vitally important. In view of the number of resources deployed at a confirmed collapse incident, the FDNY IC must also ensure that a separate radio frequency is established solely for command-level communications. Experience has proven that the implementation of a command channel provides for streamlined communications, making for a safer and more efficient operation. Battalion chiefs, with the assistance of their assigned aides, monitored the tactical and command channels, providing the operations section chief with situational awareness from each of their respective sectors on W. 56th, W. 57th, and W. 58th Streets.

Operations

The obvious differences between initial fire department operations at incidents where a structure is in danger of collapsing and operations at which a structure has already collapsed are the search/rescue and evacuation components. In the latter case, immediate search, rescue, and removal of surface victims is a high priority; in the former case, more attention is given to evacuating civilians in exposed buildings. After removing all people in imminent danger from the street in the area directly below the hanging boom, units began full evacuation of the adjoining buildings. Operating in the most severely exposed buildings first, the plan was for an orderly but expedient evacuation of all buildings on W. 57th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues.

|

| 5 |

However, after closer evaluation by DOB engineers, the IC and OSC determined that there was the potential that the tie-backs securing the crane to the building could dislodge and cause the entire 75-story mast to collapse. The collapse danger zone was then expanded to include all buildings on the south side of W. 58th Street and the north side of W. 56th Street from 6th to 7th Avenues. It took a fourth alarm and several hours to complete evacuating all 34 buildings in the designated area.

Every major collapse operation needs special resources to support the responding engine and ladder companies. The FDNY is fortunate to have highly trained rescue and collapse rescue units assigned to each of the five boroughs that are available to respond at all times. These units are equipped with all the equipment needed to perform the tunneling, trenching, and shoring commonly required at such operations. Other special and support units from the FDNY Special Operations Command available to provide expertise, tools, and equipment at a major collapse operation include the hazmat unit, support ladder companies, a tactical support unit, a dewatering unit, a compressor truck, and a logistics support vehicle. Additionally, FDNY Emergency Medical Services will dedicate to the incident advanced life support and basic life support resources, including rescue paramedic ambulances whose personnel are trained to provide patient care within collapse zones and confined spaces.

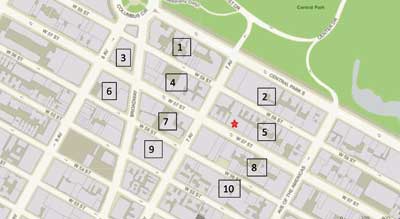

| Crane Collapse Area: Block Numbers |

|

With no immediate need for search and rescue, the first arriving engine, ladder, and rescue companies proceeded to the 75th floor to assess the damage at that level. The extreme conditions made evaluating the damage to the crane and the condition of the hanging boom section much more precarious than under normal circumstances. Safety lines were deployed to secure FDNY members and DOB engineers as they approached the perimeter of the building to take photos and make an appraisal. Once this initial assessment was completed, all operating personnel were ordered out of the building until the next day when conditions were forecast to be significantly improved. A surveyor’s transit was deployed but proved ineffective for monitoring purposes because it was continuously alarming. All units were advised that the swaying boom constituted a continuous collapse hazard until further orders. The IC determined that there would be no attempt to secure the boom until a certified crane engineer formulated a plan that was acceptable to DOB. Over the next six days, FDNY Rescue Co. 1 provided technical advice to DOB and a safety team for the contractors working to secure the crane (see “Crane Collapse: Rescue 1 Operations,” page 80).

Planning

At large-scale incidents, especially those with the potential to extend past one operational period, the IC must ensure that the Planning Section is established. The FDNY accomplishes this by assigning a battalion chief to assume the role of the Resource Unit leader (RUL) to all incidents requiring a second or greater alarm and major emergencies such as building collapses (signal 10-60). The RUL reports to and remains at the ICP and performs the following duties: accounts for all resources at the scene, maintains the command board, records and updates the status of all resources, ensures adequate resources are held in reserve, and identifies the sectors/groups to which chief officers and units are assigned. When an incident reaches the level of a fourth alarm, a special-trained battalion chief is assigned and designated the Planning Section chief (PSC). To assist the PSC, a trained engine company will respond with a well-equipped planning vehicle that can produce various documents, such as maps and incident action plans, and is also large enough to comfortably host approximately eight to 10 people for an interagency meeting. With FDNY units engaged in the evacuation of 34 buildings, the RUL was charged with the challenging task of providing accountability for each unit on the scene, recording this information on the command board, and providing situational awareness for the IC and the PSC.

● JOHN SUDNIK is a 28-year veteran of the Fire Department of New York. He is an assistant chief and is assigned as the Manhattan borough commander. He has an MA in security studies (homeland security) from the Naval Postgraduate School.

Crane Collapse: Rescue 1 Operations

BY ROBERT MORRIS

On October 29, at 1433 hours, Rescue 1, with Lt. Tom Donnelly in command, was assigned with the other first-alarm units to a reported crane collapse on W. 57th Street.

They arrived with the other first-due units. Battalion 9 assigned them to approach the area of the collapsed crane at approximately the 73rd to the 75th floors. They located a hoistway elevator used by building workers and assessed it to see if it was safe to use. No one on site could determine its fitness for use, and considering the wind speed it was decided not to use it. Our members began climbing 75 floors to reach the collapsed crane. Portable radio communication was very difficult because the stairways were encased. The members stopped at selected floors and reported on our progress in climbing.

As the first of the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) members to arrive at the collapse site, we sized up the conditions. The upper portion of the crane had collapsed in a side-to-side fashion and was hanging over W. 57th Street. Wind speed was in excess of 50 miles per hour. For safety in observing the crane in preparation for giving an assessment to the command post, our members were secured with high-angle ropes.

I reported our unit’s findings to the rescue operations chief and continued with the assessment of the crane’s vulnerability. Based on my findings, I recommended that the collapse zone be increased.

When the rescue battalion arrived, cell phones were used from several vantage points to take photos of the area; these pictures were then relayed to the command post. Rescue 1 members attached to high-angle ropes had also taken photos. By this time, Squad 18 had arrived at the roof area and assisted in this operation.

Rescue 1 also had secured loose debris, which was flying everywhere and was a danger at the roof level. For safety, these members were also secured by high-angle ropes.

Department of Buildings (DOB) personnel and engineers arrived some time later. FDNY members secured them with safety lines so they could safely evaluate the collapsed crane and its adjoining damaged parts. All information was relayed to the command post.

October 30

Rescue 1, under my command, in high winds, climbed to the 75th floor to assess the safety of the site, check all the crane tower tie-backs, and secure any materials that were blown loose in preparation for a full assessment by DOB personnel and the crane’s owner/operator. Rescue 1 set up high-angle ropes. Once all areas were deemed safe, DOB personnel and the crane operator entered.

October 31

Manhattan Borough Division 3, Rescue 1, and the DOB conferred on a plan to rotate the crane manually and secure it to the building.

November 2

We prepared to implement the plan the DOB and the Manhattan Borough had formulated. A task force was set up with equipment and remained on site during the moving and securing of the crane.

November 3

Rescue 1, under my command, and the Task Force, with Lt. John Tobin in command, responded to the site and set up a high angle rope system. In addition, two Rescue 1 members climbed up the tower structure into the crane to set up slings and the required safety equipment. The two units remained on scene during the movement and securing operations. In addition, Rescue 1 assisted with the equipment needed to complete the tie-off of the crane boom to the building.

The crane was secured with three large steel I-beams that were attached to the floor slab on the 74th floor. These beams provided one lateral brace to “butt” the boom to the floor slab. Also, two suspension beams were used to carry the 25,000-pound boom. Beams 15 inches × 30 inches × 15 feet were used for the lateral beam; the size of the suspension beams were 24 inches × 55 inches × 28 feet. The boom was now secured with one-inch wire rope slings held with two eight-ton chain hoists.

November 4

Rescue 1 and the Task Force set up high angle ropes, and Battalion 9 operated at the site until the operation was completed and the collapsed crane boom was secured.

A major concern before the crane’s boom was secured was the presence of a major high-pressure steam main and a high-pressure natural gas main on W. 57th Street directly under the crane. The utility company had mitigated the threat they posed.

ROBERT MORRIS is a captain in the Fire Department of New York, where he has been a member since 1973. He has been the commander of Manhattan’s Rescue 1 for 11 years.

Fire Engineering Archives