|

| (1) This barge broke away from its mooring in Staten Island, New York, during Hurricane Sandy and ended up grounded. (Photos by Steve Spak.) |

BY MARY JANE DITTMAR

Hurricane. Superstorm. Cyclone. Frankenstorm. The name of the storm that struck the East Coast at the end of October 2012 may vary, but there is no doubt that it was a momentous event that delivered more disastrous results than some weather experts predicted and that surprised even veteran emergency personnel. “It was a storm that remade the landscape and rewrote the record books” is how reporter James Barron of the New York Times evaluated it.

The storm’s scope was extensive, and damages have been estimated at billions of dollars. Initially, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie called the damages “incalculable.” A government model noted that the wind damage alone could have caused more than $7 billion in economic losses. Christie ultimately declared $37 billion in damages for the state of New Jersey. To put this figure in historical perspective, 539 federal disaster declarations were listed in a Government Accountability Office report that covered the period from 2004-2011. Together, the events cost about $90 billion in damages; about $40 billion were from Katrina alone. Payments for New Jersey disasters over those years totaled $35 million.

Although this coverage focuses primarily on the damage and emergency responses in the severely hit states of New York and New Jersey, other states (ultimately a total of 24 states) experienced Sandy’s fury as well. More than 8.2 million homes and businesses across the East were without power. Airlines canceled more than 15,000 flights around the world.

- Hurricane-force winds created havoc from Virginia to Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

- The mountains of West Virginia and Maryland experienced two to three feet of snow. At least 36 roads in West Virginia were closed because of high water, down trees, and snow. The roofs of some businesses in Craigsville (WV) collapsed under the weight of the snow.

- In North Carolina, Sugar Mountain Ski Resort had snow estimated to be from 10 to 16 inches.

- In Tennessee, Newfound Gap received 22 inches of snow.

- In Maryland, untreated sewage from a failed treatment plant entered the Patuxent River, and four unoccupied row houses were reported to have collapsed in Baltimore.

STATE OF EMERGENCY DECLARATIONS

Federal State of Emergency declarations were issued for the states of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York in October; for Delaware, Maryland, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia in November; for Massachusetts and the District of Columbia in December; and for Pennsylvania and Ohio in January 2013. On October 28, 2012, President Obama signed emergency declarations authorizing funds in response to the requests for federal assistance from New York and New Jersey; these states requested aid before Sandy’s arrival. This made it possible for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the National Guard, and the military and other federal agencies to immediately strategically deploy resources.

DEATHS

Before arriving in the United States, Sandy had caused the deaths of 71 people in the Caribbean, including 54 in Haiti. By the end of November, at least 125 people died in the United States, including 60 in New York State (48 in New York City). Thirty-four died in New Jersey, 16 in Pennsylvania, and seven in West Virginia. (These numbers have undergone several revisions). New York State fatalities included an 11-year-old and his 13-year-old friend who were killed when a 90-foot-tall tree crashed into the family room of a house in North Salem, New York. Another New York State fatality was Arthur Kasprzak, 28, of the New York Police Department. After leading seven members of his family to higher ground and safety in their home, he drowned in his basement when he went to check on its condition.

|

| (2) The conflagration in Rockaway Park, New York. At Beach 114th to Beach 115th Street and Rockaway Beach Boulevard, three blocks of stores and commercial buildings were destroyed. The firehouse is only a few blocks away, but the storm surge created chest-high water levels, making it impossible to fight the fires. |

POWER OUTAGES

More than 8.4 million people in the United States—about 2.8 million-plus in the Northeast—lost power. As of the morning of October 30, outages in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic states were as follows:

- New York City and Westchester: 846,549—Consolidated Edison.

- New Jersey: 975,081—Jersey Central; 1.1 million—Public Service Electric & Gas; 168,728—Atlantic City Electric.

- Long Island: 922,823—LIPA.

- Connecticut: 433,541—Connecticut Light & Power.

- Massachusetts: 135,120—National Grid.

- Delaware: 24,638—Delmarva.

- Pennsylvania: 182,713—West Penn Power; 330,905—PPL.

- West Virginia: 147,053—APCO.

- Maryland and Washington, DC: 5,351—Pepco.

- Virginia: 52,539—Dominion Electric.

- New Hampshire: 96,287—PSNH.

- Rhode Island: 98,396—National Grid.

- Maine: 17,504—Central Maine Power Company; 85—Bangor Hydro Electric Power Company.

The power companies estimated it would take at least a week, possibly longer, to restore power because of extensive damage. The companies called in thousands of repair crews from around the country.

|

| (3) Three major fires occurred in the Rockaways during Hurricane Sandy. Firefighters were hampered by the high storm surge. This fire was in Belle Harbor, Queens; almost three blocks of structures were destroyed. On November 1, 2012, this firefighter statue was the only thing standing after the massive fire. A firefighter probably owned this home. |

Alfred Gerber III, safety and training officer, Little Ferry (NJ) Hook and Ladder Co #1, reports that power in some areas in New Jersey was out for two weeks; power was out for more than a month before it was restored in some other towns.

SANDY VS. KATRINA

Sandy has the potential to exceed Hurricane Katrina (2005) as the most costly storm ever in the United States. After Katrina, Congress not only funded repairs to existing levees but also approved money for the Army Corps of Engineers to build long-planned projects and new ones that studies found would prevent future catastrophic losses. California was able to have bridges and highways rebuilt after earthquakes to meet more quake-resistant standards.

|

| (4) Sandy destroyed most of the waterfront homes in Neponsit and Belle Harbor. |

Sen. Mary Landrieu (Louisiana), chairman of the appropriations subcommittee that would write a spending bill for Sandy, had suggested to President Obama that a new Disaster Recovery Block Grant be created to help communities rebuild.

|

| (5) This home in Seagate, Coney Island, New York, was totaled. |

“This was an epic storm and needs an epic response, and I hope it doesn’t get caught up in debates in the House and Senate on how best to face the [fiscal] cliff,” asserted New Jersey Rep. Bill Pascrell Jr.

NEW YORK-NEW JERSEY PREPARATION

In the states of New York and New Jersey, responders, emergency management personnel, and community officials were bracing for a record-setting storm. The National Weather Service (NSW) forecasts warned of the presence winds of from 39 to 55 miles per hour (mph) on the evening of Sunday, October 28, 2012, and from 40 to 60 mph from Monday evening into Tuesday, October 29-30. Buildings more than eight stories high and bridges could experience 70- to 80-mph winds. Moreover, these high winds could last for 12 to 18 hours before returning to the 39- to 55-mph range.

|

| (6) Fire Department of New York units searching for possible survivors in Staten Island houses the day after the storm. |

Compounding the situation was that the storm’s arrival was to coincide with high tides and a full moon, factors that signaled to emergency personnel that Sandy would be producing copious amounts of flood waters.

On October 27, the NWS information obtained at a Coastal Storm Committee Teleconference, which was attended by personnel from the Fire Department of New York (FDNY), indicated that Sandy at that time was classified as a Category 1 hurricane and that the exact area of its landfall was not known. This information was not significant, however; the storm was so large that it would affect the entire area regardless of where it originally made contact with land.

|

| (7) This Staten Island house was washed off its foundation. |

What was becoming very clear to the emergency personnel preparing for this event was that it would necessitate vast resources and that the affected areas would likely see unprecedented damages. These dire expectations ultimately led to some “firsts” for the New York area, including the cancellation of the 2012 New York City Marathon and the closing of the New York Stock Exchange for two days, its first closure caused by inclement weather since the blizzard in 1888.

Emergency personnel and government officials began preparing for the storm and the well-being of responders and civilians long before the storm’s arrival.

|

| (8) Damaged home on Fire Island. |

The New York Bureau of Operations arranged for FDNY liaison staffing in the New York City (NYC) Office of Emergency Management (OEM), coordinated with OEM the opening and setting up of shelters in the five New York boroughs for residents evacuated from the storm surge areas, and arranged for staffing to support civilians in the evacuation zones. (See “Calm Before the Storm: FDNY Preplanning and Preparation,” page 24.)

In New Jersey, preparations included activating the statewide urban search and rescue team (US&R) New Jersey-Task Force 1 (NJ-TF1), whose more than 200 members are trained in all aspects of specialized rescue, and implementing the Urban Areas Security Initiative (UASI) program, a network of county-based units comprised of members of career fire departments mainly from urban areas bordering NYC. The units are set up as smaller US&R teams and normally respond before the state US&R teams.

|

| (9) Fire Island damage as of January 9, 2012. |

As soon as New York and New Jersey had requested and President Obama approved federal assistance, FEMA had staged two US&R teams, one from Ohio and the other from Virginia, at the military base in Ocean County, New Jersey, and components of the FEMA Level 1 Incident Support team (IST) were sent to New Jersey. [See “Superstorm Sandy: New Jersey’s US&R Response” in Part 2 (June issue).]

STORM SURGE

Storm surge often is the most deadly and damaging inpact of a hurricane. Driving winds quickly push water to create mounds of water higher than the normal sea level. As a storm approaches land, the storm surge, which can be capped by large waves, can be pushed up the coastline and deep into inland areas.

|

| (10) Inside a flattened home on Staten Island. |

The storm hit NYC on Monday, October 29, 2012, at the peak of high tide and during a full moon. The surge was 13.8 feet, and winds were sustained at 65 mph; gusts went up to 92 mph. There were large masses of water. The additional water accumulated in bays and harbors and formed large lakes and streams.

The surge set records in lower Manhattan. “The Hudson River surged onto West Street in lower Manhattan near the World Trade Center (WTC). Millions of gallons of water cascaded into the 9/11 memorial footprint and flowed into the PATH tubes,” observed FDNY Battalion Chief Joseph R. Downey, Rescue Battalion, and leader of NY-TF1. “The two tunnels from the WTC station to Exchange Place in Jersey City became flooded, and beachfronts on both sides of Long Island Sound were savaged,” he added. (See “FDNY Assists with Odd Job in the PATH Tubes,” page 97).

|

| (11) Hurricane Sandy damage at the Seaside Heights (NJ) Funtime Pier Amusement Park as of December 23, 2012. |

In New Jersey, sections of the barrier islands throughout Ocean County and the low-lying areas in Monmouth, Atlantic, and Cape May counties were under eight to 12 feet of water.

SANDY’S EFFECTS New York

Even experienced and seasoned responders were astounded by the storm’s power. “There were cars sitting on top of each other, on their sides, sitting on park benches, strewn across the median divider; trees were on top of them everywhere you looked,” recalls FDNY Lieutenant Michael Ciampo. “We were shocked that the fury of the ocean did this much damage to the vehicles a mile away from the ocean.” (See “Working the Streets: Rapid Response Vehicle Operations,” page 83.)

It was estimated that 7,000 trees were down in the NYC parks.

|

| (12) The iconic rollercoaster in the water at Seaside Heights, New Jersey. |

In fact, the extent of water damages caused by Sandy has led FEMA to revise its advisory flooding maps for Manhattan to include additional sites at risk during a powerful coastal storm, including the WTC site, sections of Manhattan’s East Village and Chelsea, and Brooklyn’s Red Hook and Greenpoint sections. Official versions of the revised maps will be available this spring and will be finalized over the next year or two and will be used to set premium rates for flood insurance and to influence building codes and other regulations.

FEMA had earlier released revised maps that added hard-hit areas of the NYC including the Rockaway seashore, Staten Island, and sections along Jamaica Bay. The new map included thousands of buildings and many square miles of land that previously had been thought to be unlikely to flood.

|

| (13) Structural searches posed a great danger to first responders. Many were conducted in coordination with US&R teams. These searches were in Belle Harbor, Queens, New York. |

At the height of the storm, the largest private residential fire in the history of Breezy Point, Queens, New York, occurred. Some 126 homes were destroyed, and 22 others were damaged (See “Conflagration in Breezy Point, Queens,” page 61.)

A construction crane on the 74th floor of a Manhattan structure collapsed in the high winds. (See “W. 57th Street Crane Incident: A Command-Level Critique,” page 77.)

Flood waters affected hospitals: One had to evacuate 200 patients; another had to use backup power from generators.

Manhattan’s Battery Park saw a nearly 14-foot tide.

About 400,000 people were evacuated from the low-lying areas of Manhattan and elsewhere.

In Fire Island, off Long Island, New York, water rose above promenades and docks.

The nuclear power plant at Indian Point, 45 minutes north of NYC, was shut down because of electric grid issues.

Water seeped into subway stations in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn and, in some stations, climbed to the ceiling. Debris covered tracks in stations up and down the lines. Seven subway tunnels between Manhattan and Brooklyn flooded.

Metro North Railroad lost power on two of its three lines. Long Island Railroad’s West Side yards were evacuated. Two railroad tunnels beneath the East River flooded. The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and the Queens-Manhattan Tunnel remained impassable. FEMA asked specialists from the Army Corps of Engineers to help with the flooded tunnels in lower Manhattan.

The $300 million of damage to the PATH train system is the most extensive in the rail line’s history and has kept the Hoboken (NJ) station closed for months. The repair estimate is more than double the annual revenues of this system that links New Jersey and Manhattan. It is estimated that rebuilding efforts will cost at least $71 billion, not including the damage to the Port Authority’s facilities.

New Jersey

On November 29, Gov. Christie estimated damages to be around $37 billion. More than 30,000 businesses and homes were destroyed or structurally damaged; numerous other homes have problems; and a thousand miles of beach are severely eroded. Christie appointed former assistant U.S. Attorney Marc Ferzan to oversee the state’s rebuilding effort.

Collectively, in New Jersey, Hurricane Sandy deposited nearly 1,400 boats, 58 homes, multiple vehicles, and countless decks and sunrooms into Barnegat Bay. It is not known how much personal property can or will be recovered. [See “Jersey Shore Ops” in Part 2 (June issue).]

Sandy left seven-foot-tall debris piles and two dozen freight train containers along the N.J. Turnpike between Exits 10 and 14. The containers were picked up by a tidal surge and dumped along the northbound side of the turnpike near Exit 12 in Carteret. Sandy cost the N.J. Turnpike Authority at least $15.4 million in labor and fuel costs and lost tolls.

At the Oyster Creek nuclear power plant in Lacey Township, waters surged six feet above sea level.

“All along an 18-mile stretch of Long Beach Island and a 13-mile stretch of the Barnegat Bay peninsula,” reports Bill Hopson, deputy fire marshal for the Ocean County (NJ) Fire Marshal’s Office, “fire departments in Ocean County found themselves in a difficult position of trying to do what they have always done while figuring out how not to become trapped by the rapidly expanding storm.”

The mainland fire departments on the barrier islands in New Jersey (which are basically sand) realized they were on their own because the bays and lagoons surrounding their communities rose to record levels and filled every nook and cranny with a combination of bay and ocean water.

In every one of the 33 communities that form Ocean County, residents’ homes were underwater or severely damaged, and the municipal water system in the outer island was in pieces or not accessible.

“As some of the first nonlocal personnel to witness the initial devastation, initial mutual-aid departments saw firsthand what we were encountering and the limitations we were experiencing,” reports Daniel P. Mulligan, Ocean County chief fire marshal. “The mutual-aid response was historic because more than 145 departments provided assistance. Many of these departments ‘adopted’ the stations they covered and continued to provide personnel, finances, and equipment. There was strong work by many of the assisting departments—because they gave us a lot of what they had. Not only did these departments provide assistance, but they also provided the much-needed reassurance that the willingness of one fire department to help another—anywhere in New Jersey—was very much the norm, not the exception.”

Mantoloking was cut into thirds by three breaches from the ocean to the Barnegat Bay. All that was visible in the borough was about five feet of sand in the roadway. Almost every power pole and its lines were lying on the ground, and you could hear the sound of natural gas blowing out of homes and in the street. Breaks in multiple water lines caused water to flow throughout the island. Sewage lines were down. All phone and cable lines were down. [See “Jersey Shore: Mantoloking OEM” in Part 2 (June issue).] In Atlantic City, part of the boardwalk was ripped up.

In Seaside Heights, 30 minutes north of Atlantic City, the north side of town was underwater; its boardwalk was damaged, and a gigantic roller coaster was relocated to the Atlantic Ocean.

On the west side of Barnegat Bay, the Silverton section of Toms River Township was partially underwater. Ninety percent of fire department members lived in the bay front area that sustained major storm damage, including the home of the chief of the department. [See “Jersey Shore Ops” in Part 2 (June issue).]

- Little Ferry, Moonachie, and Carlstadt were flooded by the Hackensack River. VA-TF1 assisted state and local responders in evacuating residents. In Little Ferry alone, Gerber reported, more than 10,000 vehicles were damaged by the storm. [See “Northern New Jersey: Flood Rescues” in Part 2 (June issue).]

- In Toms River, there were 400 water rescues. Many people were trapped by the storm surge.

Amid all this devastation, the number of emergency services apparatus that experienced operational issues was rapidly expanding, and the apparatus had to be removed from service.

MUTUAL AID

Because so many departments that normally would have provided mutual aid to Sandy-stricken communities were also facing destruction of their communities, departments, and responders’ residences, assistance came from outside their geographic areas. Departments with boats or vehicles designed for high water, for example, came to rescue residents in Little Ferry and Moonachie as did the N.J. State Police with military vehicles; FEMA US&R members from Fairfax, Virginia; and the Leonia (NJ) Fire Department with its rescue boat. Bergen County-TF-1 was deployed to Toms River and adjacent areas. [See “Statewide Mutual-Aid Deployment to Toms River” in Part 2 (June issue).]

Because fire departments in stricken counties had multiple apparatus out of service and their personnel were physically exhausted, county mutual aid in the form of task forces and strike teams responded throughout the state. New Jersey invoked the New Jersey Emergency Rescue Deployment Act to consolidate resources through the N.J. Fire Coordinating System with the full support of the New Jersey Division of Fire Safety, explained Ocean County (NJ) Chief Fire Coordinator Brian Gabriel. Within 24 hours, nearly every county in New Jersey began sending apparatus and personnel, which were rotated in the geographical areas that were hardest hit. Regional staging areas were established, and task force and strike teams were logged in and given 24-hour assignments. After the initial 24-hour deployment, the task forces and strike teams were rotated out.

FEMA ASSISTANCE

FEMA had activated/alerted 13 US&R task forces and deployed nine. It deployed the Red US&R IST, which provides command, control, and coordination for federal resources committed to US&R operations. US&R liaison officers were also deployed to the command centers in the federal, state, and local system to establish better communication, coordination, and resources. Three FEMA National Incident Management Assistance Teams (IMATs), 11 regional IMATs, and one FEMA Headquarters IMAT were deployed.

Sandy has left New York and New Jersey with many scars and indelible impressions and numerous lessons learned (which will be covered in “Special Issue: Hurricane Sandy Response, Part 2,” June 2013 Fire Engineering). In the spirit of the American fire service, these lessons will help the emergency services and federal, state, and local governments to fortify against the ravages of future storms.

Bibliography

Barron, James. “After the Devastation, a Daunting Recovery.” The New York Times, Oct. 30, 2012.

Boburg, Shawn. “$300M to repair PATH.” The Record. Nov. 28, 2012.

Boburg, Shawn. PATH: “‘Weeks’ before Hoboken reopens.” The Record. Nov. 28, 2012.

Carbone, Nick and Madison Gray. “Hurricane Sandy’s Wrath: Track Power Outages by State.” http://newsfeed.time.com. Oct. 30, 2012. Accessed March 15, 2013.

Federal Emergency Management Agency Web site, www.fema.gov.

Federal Emergency Management Agency. “New FEMA flood maps for NYC include WTC site” press release. http://online.wsj.com accessed Feb. 27, 2013.

“A month after Superstorm Sandy, death toll is at 125 in US: damage estimated at $62B,” http:www.foxnews.com. Accessed March 13, 2013.

Frassinelli, Mike. “Sandy took big bite from toll roads’ budget.” The Star-Ledger, Nov. 26, 2012.

Hayes, Melissa and Herb Jackson. “N.J.’s storm bill: $37B.” The Record. Nov. 29, 2012.

HuffingtonPost.com. “Hurricane Sandy Aftermath: Storm Leaves Millions Without Power, Dozens Dead.” Accessed Nov. 15, 2013.

Hurricane Central. “Sandy’s Snowy Side turns Deadly.” http://www.weather.com/news/weather-hurrrricanes/sandy-snowy-side-20121030.

Jackson, Herb and Melissa Hayes. “Scope of post-Sandy aid subject of debate.” The Record, Nov. 30, 2012.

Linhorst, Michael. “Process starts in Sandy recovery.” The Record, Nov. 27, 2012.

“Officer drowns saving family from surging Sandy.” http://www.policeone.com, Accessed March 13, 2013.

Superville, Denisa R. “First responders endure after flooding.” The Record. Nov. 29, 2012.

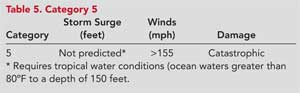

Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale

Hurricanes are powerful storms that develop over the equator in warm ocean waters and travel toward the North and South poles. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s hurricane forecasters use this scale to help clarify the predicted hazards of approaching hurricanes for emergency managers and aid in estimating property damage and flooding expected along the coastline. The scale, formulated in 1969 by Herbert Saffir, a consulting engineer, and Dr. Bob Simpson, director of the National Hurricane Center, classifies storms into five categories.

This category storm generally does no real damage to building structures. The damage is primarily to unanchored mobile homes, shrubbery, and trees. Some coastal road flooding and minor pier damage can occur.

Example: Hurricane Sandy killed at least 125 people in the United States. This includes 60 in New York (48 of them in NYC). Estimated damage and losses (72,000 homes and businesses in New Jersey alone) in the United States as of the middle of January were $62 billion.

Anticipate some roofing material, door, and window damage to buildings. There is considerable damage to vegetation, mobile homes, and piers. Coastal and low-lying escape routes will flood two to four hours before the center of the hurricane arrives. Small craft in unprotected anchorages will break moorings.

Example: Hurricane Bob made landfall twice in Rhode Island as a Category 2 hurricane on August 19, 1991 (first on Block Island and then in Newport). Seventeen fatalities were reported in association with this hurricane. In addition, it left damage totaling approximately $1.5 billion throughout New England in its wake.

Small residences and utility buildings will experience structural damage (curtain wall failures, for example). Small structures along the coast will be destroyed by flooding; larger structures will be damaged by floating debris. Mobile homes are destroyed. Terrain that is continuously lower than five feet above sea level (ASL) may be flooded inland for eight miles or more.

Example: Hurricane Katrina (second landfall on the morning of Monday, August 29, 2005, in southeast Louisiana). At least 1,833 people died in the hurricane and subsequent floods; total property damage was estimated at $81 billion.

Extensive curtain wall failures with some complete roof failure on small residences will occur. Near the shore, there will be major damage to the lower floors of structures. Terrain that is continuously lower than 10 feet ASL may be flooded, requiring massive evacuation of residential areas inland as far as six miles. There will be major erosion of beaches.

Example: On August 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew hit South Florida and continued northwest across the Gulf of Mexico to strike the Louisiana coastline. In all, the storm caused 15 deaths directly, 25 deaths indirectly, and $30 billion in property damage. More than 250,000 people were left homeless; 82,000 businesses were destroyed or damaged. Hurricane Andrew also had a severe impact on the environment: Thirty-three percent of the coral reefs at Biscayne National Park were destroyed, and it created 30 years worth of debris.

Many residences and industrial buildings will experience complete roof failure. Some buildings will collapse completely; small utility buildings will be blown over or away. Major damage will occur to the lower floors of all structures less than 15 feet ASL and within 500 yards of the shoreline. Massive evacuation of residential areas on low ground within five to 10 miles of the shoreline may be required.

Source: Fire Department of New York. All Unit Circular 159, Addendum, “Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale,” October 6, 2009. Prepared by Ronald Spadafora, assistant chief, Fire Department of New York; Retrieved 11/27/12 at: http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/laescae.html.

● MARY JANE DITTMAR is senior associate editor of Fire Engineering and conference manager of FDIC. Before joining the magazine in January 1991, she served as editor of a trade magazine in the health/nutrition market and held various positions in the educational and medical advertising fields. She has a bachelor’s degree in English/journalism and a master’s degree in communication arts. She writes a health and a technology column for fireengineering.com.

Fire Engineering Archives