By Richard Mueller

Last month I discussed a four-part approach to strategy called “FORE strategy,” from the book Fire Company 4. This is a systems approach to fire-service quality and sustainability that is Focused on Reducing Errors (FORE), namely errors that directly and indirectly result in fire company damage, disease, and death. This month I will focus on the first of this four-pronged approach, the defensive strategy, and why it should be our first thought rather than our last.

Tragedies of Strategies

On July 26th, 2010 two firefighters were killed1 when the fire apparatus they are riding in failed to stop on red and they were both ejected from the collision because they were not wearing seat belts. On December 4th, 2009 a responding engine made the same error and collides with a van carrying seven special needs adults. One occupant was killed and 14 others (including six firefighters) were injured. An even more unbelievable example of offensive strategy gone bad occurred on February 23, 2012, when a firefighter rolled his privately owned vehicle three times after colliding with another car at the scene of a deadly house fire. After the vehicle stopped rolling, the firefighter got out of his vehicle, and, despite being injured, donned his personal protective equipment (PPE) and joined his other fire department members in their attack. An offensive strategy out of the gate wouldn’t be a problem if emergency vehicle collisions where few and far between. However it does not take a whole lot of time or effort (research) to see that responding and returning from incidents account for nearly 25 percent of our annual deaths2 and more than 6 percent of our annual injuries3. When we factor in the collateral damage to civilians, the numbers are even more staggering, embarrassing, and humbling.

Each year approximately 200 civilians are killed and more than 16,000 are injured as a result of collisions with emergency vehicles4. The truth is that more civilians are killed and injured as the result of collisions with emergency vehicles than firefighters. To make this even clearer, more civilians are injured from collisions with emergency vehicles than from the place that we are all in such a hurry to get to–structure fires! Although I must acknowledge that many more civilians are killed at residential structure fires than from accidents with responding apparatus, the answers to reducing all of these deaths is not found by responding even more aggressively but rather, first, by arriving; second, by deciding how we are going fight when we get there (PREVIS2OS tactical decision making model5); and thirdly, aiding in what the civilians do before our arrival (by providing working smoke detectors and advocating for residential sprinkler systems). I will address the significance of these in future transitional and marginal strategy articles. It does not benefit anyone when we do not make it to the scene or create casualties along the way. We should not be in the business of creating new customers!

A change of thinking is needed if we want to avoid the carnage that results from incidents like these. The tactical errors of driving too fast, failing to stop on red, and not wearing seat belts are the result of our routinely applied automatic “aggressive offensive attack” mindset (strategy) whenever the tones go off. A change of thinking from an aggressive offensive response to a more conditional defensive strategy followed by corresponding changes of defensive behaviors will reduce the many deaths and injuries accumulated during our response.

The Defensive Strategy

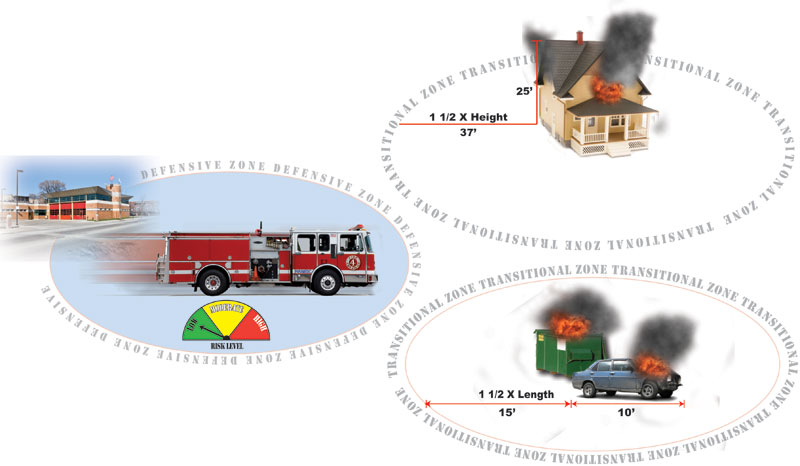

The defensive strategy is defined as an exterior attack/tactics performed outside of the collapse zone that ensures fire company arrival and exposure protection.The defensive strategy does not start at the scene of a fully involved structure but rather wherever the call is received. Whether it is in a firehouse, your own home, or anywhere in between, wherever firefighters are alerted to respond, our primary thoughts and actions should be more about getting there rather than what awaits your arrival. This defensive strategy is defined geographically by a defensive zone that starts at the place where the call is received and ends at the collapse zone (figure 1). The collapse zone is defined as 1 ½ times the height of the structure or 1 ½ times the length of a vehicle. Too often we too quickly pass through or take for granted this hazard zone area between where the call is received and the incident location. Our vision becomes focused on speed and time. We fail to see the big picture, which includes the lives that are not yet part of the incident until they run afoul of firefighters experiencing tunnel vision because of a default “aggressive offensive interior attack” mindset.

A defensive strategy is acted out with defensive tactics and actions that include:

- wearing seat belts

- traveling at a reasonable speed (within 10 MPH of the posted speed limit), and

- stopping at red lights.

When we arrive, a conscious and deliberate decision needs to be made based on a risk-versus-reward profile. When there is potential to save savable lives and property, the defensive strategy should be upgraded to transitional to better determine (evaluate) the possibility and probability of success rather than an offensive “luck and ego” roll of the dice. When success is determined to be low, large lines, master and elevated streams should be deployed to protect and save the uninvolved. All efforts should be made to keep everyone out of the collapse zone and any products of combustion. If the products of combustion extend outside the collapse zone, the defensive zone should be expanded and any fire companies working in them should be protected with PPE and self-contained breathing apparatus. These are not the most popular decisions, or the ones we most look forward to, but they are necessary to prevent incidents such as the one that occurred on June 18, 2011, in which a firefighter was killed by a partial wall collapse during a defensive fire attack6.

The risk in the defensive zone should be low when we chose to act defensively. There can be no such thing as “no risk” (i.e., we will not take any risk for lives and property that is already lost) when we operate heavy equipment, hydraulic systems, pressurized hoselines, and a variety of powerful tools in the defensive zone. Additionally, environmental conditions can include from temperatures over 100º F to well below zero, precipitation (solid and liquid), and extreme brightness or darkness. There is always a risk to anyone working directly with, in, or around such scenes and hazards. Our incidents also attract (and distract) spectators. We need to define and follow Level 1 and Level 2 staging parameters that protect the scene and the firefighters working in the defensive zone. Waiting for the police to do this or not “doing what we can with what we have” is a defensive human error.

Expanding the defensive strategy from “surround and drown” to include these responding risks ensures that more fire companies make it to the scene with little to no collateral damage. The defensive strategy has matching defensive behaviors that include:

1. Always wearing a seat belt. Unrestrained fire company members place themselves and the other riders in their apparatus at unnecessary risk when they are not seated and belted. Emergency responses with some of the largest pieces of apparatus allowed on the roadway include many unknowns. Fire company members should be prepared for sudden stops, turns, collisions, or even rollovers. Even when we do everything right, the other motorist may not. Civilians may be driving with distractions, and the last thing on their mind is probably encountering an aggressive, offensively driven fire apparatus.

2. Always stop on red. Do not mix your signals! Green means go and red means stop. There are a million excuses why fire company members minimize the importance of this simple and straightforward behavior. After reading and investigating too many intersection collisions, it is crystal clear to me why we stop on red. Every opportunity that I have had to ask a driver/operator who has been involved in an intersection crash the question of why has returned the same answer: the operators either did not see the other drivers coming or they suddenly appeared out of nowhere. The only way to ensure that fire company members see them coming is to stop on red and verify that each lane is clear before proceeding. Blowing a red is a clear and dangerous example of an unbalanced strategy.

3. Keep speed within 10 miles over the posted speed limit. This is for ideal conditions. Weather, construction, terrain, and other natural, and man-made conditions may necessitate a speed below this. Fire engines are not sports cars and they do not stop like one (even though they are both routinely painted red). Although our fire apparatus have no trouble getting up and going at a high rate of speed, stopping is a different story, especially when compared to the passenger cars that we share the road with. With stopping distances two to three times that of a car, the only option at times to avoiding a crash is to attempt an offensive driving maneuver and go around them. Unfortunately, this is not always an available option, or an option that allows the driver/operator to maintain control of our top-heavy vehicles. When collisions occur with passenger, civilians are killed and injured many more times than we are. Control is not just at the “moment” but more at the “moment of truth” when we have to stop rather than when we merely want to.

4. When there is no reward, stay defensive. Fire companies that respond with a defensive mindset are forced to make a conscious decision to move beyond their defensive strategy and assume more risk because of a just reward rather than to simply continue on the path of an aggressive offensive attack strategy because it feels good. There is a critical step in determining if we move to portable handlines and tools or continue with our defensive thinking and behaviors, such as using big water and big lines operated outside of the collapse zone.

Incidents that do not transition out of the defensive strategy are typically long in duration. A decision to stay defensive after arrival is a decision to maintain the defensive attack position for an extended (long) period of time because there is nothing to gain. Defensive strategy decisions should not be upgraded in a short period of time. If there was nothing to save initially, it is doubtful that there will be more to gain later.

**

A defensive strategy reminds you to take the time to buckle up, bring the apparatus to a complete stop at red, pull your foot out of the fuel injectors, and stay out of the collapse zone when there are no lives and property to be saved. Responding with a defensive mindset at the start of an incident reduces our stress and anxiety by slowing our heart and respiratory rates; it allows us to replace an “all-or-nothing” mindset with a more controlled outlook, rather than an “OMG it’s a fire” mentality. Showing up in control rather than like a bat out of hell is our best opportunity to staying in control, and never losing control7 and just maybe another piece of the solution to reducing our cardiac-related fatalities at incident scenes8.

1. “Volunteer Chief and Firefighter Die after being Ejected During a Rollover Crash,” NIOSH Report F2011-15, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face201019.pdf

2. “Firefighter Fatalities in the United States – 2010,” NFPA http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files/pdf/osfff.pdf

3. “U.S. Fire Service Firefighter Injuries by Type of Duty,” NFPA http://www.nfpa.org/itemDetail.asp?categoryID=955&itemID=23466&URL=Research/Fire percent20statistics/The percent20U.S. percent20fire percent20service&cookie percent5Ftest=1

4. “IAFC Informational Paper on Technology for Citizen Notification of Responding Emergency Vehicles,” July 21, 2011, http://911eta.com/911ETA-White-Paper-w-cover.pdf

5. PREVIS2-OS is an acronym for a tactical decision making model that priorities the tactical decisions to accomplish a Perimeter Check (360), Rescue (Visible), Exterior Attack, Ventilation (Positive pressure), Interior Attack, Primary and Secondary Search, and Overhaul and Salvage When Appropriate (from the Fire Company 4 textbook.)

6. NIOSH Report F2011-15, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/

7. “Start in control, stay in control and never lose control” is a phrase used often by Alan Brunacini.

8. Cardiac related deaths are the number-one cause of firefighter fatalities. “Firefighter Fatalities in the United States – 2010,” NFPA http://www.nfpa.org/assets/files/pdf/osfff.pdf

Richard Mueller is a battalion chief for the West Allis (WI) Fire Department. He is a fire instructor for Waukesha and Gateway Technical College and a technical rescue instructor for the WI REACT Center. He is a member of the Federal DMORT V and WI Task Force 1 Team and a Partner with the WI FLAME Group. He is the author of the firefighting textbook Fire Company 4and can be reached at Rick@Wiflamegroup.com