By Craig Nelson and Dane Carley

Where We’ve Been

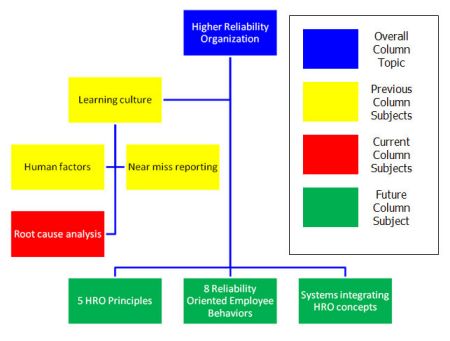

Building a

higher reliability organization (HRO) means employing multiple, complex concepts. Therefore, we thought it would be easier to see where we have been so far and how those ideas fit into the

HRO idea by placing the article topics into a familiar chart. We are going to use something similar to an incident command system (ICS) organization chart to illustrate what we have covered and how it fits into the HRO idea.

Root-Cause Analysis and the Chain of Errors

Previous columns

introduced the HRO concept and some of the key components used to build an HRO with the intention of changing the fire service’s perspective on operations. It is necessary to gain an overview of these topics (Tailboard Talk #1) because each is dependent on another, but each is a lengthy discussion of its own. HROs thrive on constant learning. Human factors (Tailboard Talk #2) and near-miss reporting (Tailboard Talk #3) are essential to ongoing learning, which were the subjects of the previous columns. However, without root-cause analysis these tools are less useful. Root-cause analysis stops the typical blame game to look for the true root cause. Such a desire to learn means acknowledging that we are all human and make mistakes.

Eighty percent of our accidents are caused by human factors; yet we usually focus on the 20 percent that are symptoms of a larger problem. We are not mathematicians (and we didn’t stay at a Holiday Inn Express last night either), but would looking at the root causes encompassing 80 percent of our accidents be more effective in reducing

line-of-duty deaths and injuries? Why does the fire service ignore such a large cause of our accidents? We would like to hear why you think so and

what ideas you have for changing the fire service perspective on finding accident causes (tailboardtalk@yahoo.com).

ROOT-CAUSE ANALYSIS

We know one reason is that the department or organization in which you work shapes how you see your world. Your reaction to an incident is

dependent on your past life experience, training, education, personal beliefs, and organizational experiences. To look outside the fire department’s box, an HRO constantly challenges itself with the critical thinking questions such as: “Are we seeing this accurately, or have we let our beliefs provide the answers to our questions without any evidence? Would someone from outside the fire service in another organization or profession see what happened the same way we do?” Critical, objective evaluation prevents the organization from returning to the simplified game of blaming a piece of equipment or lack of engineering when the true root cause probably lies within the organization’s culture, leadership, training, disciplinary processes, firefighter personality traits, and public expectations. For example, the fire service designs another bell and whistle to identify a firefighter not wearing a seat belt (a symptom) instead of shaping the firefighter’s behavior through identifying the root cause.

HROs recognize already existing and ongoing organizational behavior research showing that employees’ behavior is a reflection of the organization’s culture. In other words, the organization’s culture that develops over years in response to administrative decisions, actions (or lack of actions), and training evolve into norms and values. Since the organization is responsible for shaping the norms and values existing in a culture, the organization heavily influences the employees’ behavior. HROs use this understanding to reduce the possibility of future accidents by performing a root-cause analysis on accidents that do happen. After identifying root causes, HROs track the reported data, build trend reports, and identify emerging trends as a holistic approach to safe operations.

Weick and Sutcliffe

(2007) describe this as an organization being “mindful,” which is a result of the five HRO principles, two of which are particularly applicable to root-cause analysis, and a root-cause analysis tool called a chain of errors. The two relative principles, as labeled by Weick and Sutcliffe (2007), are

- Principle One: a preoccupation with failure

- Principle Three: a sensitivity to operations

This column will begin to explore the five HRO principles in depth soon after explaining a few key topics used within the five principles. In the meantime, here is a summary of the two relevant principles. First, HROs recognize in

Principle One that since humans operate the organization’s system, accidents are inevitable. We all make mistakes (if you don’t believe us, then ask your spouse). HROs use these near misses and accidents as learning opportunities. HROs believe that a near-miss error is a symptom of a larger systemic problem worth identifying and changing before it disables the organization. The constant desire to learn reduces the tendency to drift into complacency. Second, HROs recognize that accidents are the result of compounding small errors, like links in a chain, coinciding at an inopportune time to end in an accident. Improving situational awareness is fundamental to the third principle to recognize a developing chain of errors. Developing a learning culture encourages others to speak up and report symptoms, which is critical to developing situational awareness. Burke, Wilson, and Salas (2005) write, “Many errors remain latent, embedded within the operational system until just the right combination of adverse events occurs.” Performing root-cause analysis continuously as part of a learning culture helps firefighters improve situational awareness by increasing their understanding of the organizational influences affecting their decision making (Carley, 2010).

Root-cause analysis is one of the most important concepts to learn about and apply when building an

HRO because it is a simple, effective analysis and learning tool. We believe this is an area in which many organizations can improve because society conditions us to prefer the quicker, easier, and publicly satisfying action of blaming and punishing someone. Is that right? Is it productive? Is it effective? Is it safe? Does it build employees up or break them down? The answer should be that we do things the way we do because it is safer, more effective, builds up employees’ abilities, or is more productive. Root-cause analysis is a tool filling the need to answer these questions because it delves more deeply into the organizational influences contributing to the decisions leading to an accident while removing the person who made the decision from retribution.

Root-cause analysis works backwards from near

-miss and time-loss incidents along the chain of errors to the behavioral root cause instead of simply saying a single person is to blame, punishing the person, and not searching out the contributing factors to the decision. It seems many organizations firmly believe that punishing someone for an unintentional act solves the problem. In truth, however, this ignores the real causes behind the incident and prevents the real changes needed to avoid the incident again in the future; therefore, not finding the root cause simply delays the inevitable from happening again. We believe that it is time the fire service started using the tools available to build a safer profession. The wildland side of fire has been doing this for a while. Have you ever looked at its incident analysis and reports?

The airlines have been doing root-cause analysis for years because they simply could not exist with too many accidents and deaths. The fire

service seems content to believe that firefighting is dangerous and that is just the way it is. We believe that firefighting is and most likely will always be dangerous, but we also believe that we have the knowledge, tools, and ability to reduce the number of incidents killing and injuring those in our profession dramatically.

Knowing the outcome of the decision after the incident is easy

, so it is disingenuous and counterproductive to learning to say the decision maker should have foreseen the same. Root-cause analysis often finds that instead of the cause being a single person intentionally making a bad decision striving for a poor outcome, human, organizational, and environmental factors contribute to the decision. In fact, we find when teaching root-cause analysis of case studies in class that they frequently lead to organizational influences that are rooted in fire service culture developed decades ago, a finding that is also supported by Kerwood (2008) in his literary review.

LINKS IN THE CHAIN

To do a root-cause analysis, we start at the incident

and work backward by examining every factor involved leading up to it. A chain of errors is a tool we can use to do this. A chain of errors works much like a timeline where each link in the chain is an item, event, action, or a behavior that led to the incident. If we remove just one of these links from the chain, we avoid the incident. It is often found that many factors leading up to an incident exist outside of the decision maker’s scope of situational awareness because the decision maker is simply operating under the premise “that is how it has always been done here.” (Does that sound familiar?) Performing a root-cause analysis helps an organization identify these factors, which is critical to an organization’s preoccupation with failure and sensitivity to operations. The contribution the chain of errors makes is that it helps to identify where an organization needs to make changes to properly prevent or reduce the chance of the incident happening again. An example is often the easiest way of showing how a chain of errors works, and we like pictures to help us learn, so we develop an example below.

Case Study

The following near-miss incident, 11-0000015, is from the

www.firefighternearmiss.com Web site. We have copied the event description and lessons learned into this case study exactly as written by the report author. However,

we were not involved in the incident and do not know the department that was,

so we are making assumptions in the chain of errors based on the near-miss report to illustrate our point. We want to thank the training officer for taking the time to submit this report in a public forum.

Event description

Personnel were operating on the scene of a structure fire in a two-story, balloon wood frame, multifamily dwelling. The near miss occurred about one hour after units were dispatched.

The fire had started in the bathroom of a first

-floor apartment. The fire had spread to the front door by department arrival. There was a three- to five-minute delay in charging the initial attack line due to pump operator error (lack of experience). The fire ignited the vinyl siding and contents of the front porch, exposing the attached porch roof to fire.

Two members were standing on the porch roof to open the exterior wall between the first and second floor for overhaul. The porch roof collapsed, falling 10-12 feet. Both firefighters were injured and transported to a nearby trauma center. One firefighter has returned to duty

; the other will not return to duty for at least two months.

The personnel failed to evaluate the stability of the porch roof before using it as a work platform. Built of 2 × 4s with a composite shingle topside and vinyl

-covered bottom side, the roof was attached to the house with nails to a 2 × 4 stringer (poor construction). No one assessed the impact of the fire to the building stability until the collapse of the porch roof. The direct flame contact resulted in heavy charring of the 2 ×4s across the underside of the porch roof. There was no accountability of incident workers in place. Incident Command had weak control of units functioning at the scene. There were some reports of freelancing by individuals due to a lack of command presence and responder discipline. There was no safety officer assigned to the incident.

Lesson learned

- Incident Command must maintain clear command and control of incident operations.

- Accountability of all incident personnel must be maintained at all times with a personnel accountability report conducted every 15-20 minutes of incident operations. A tactical command board with an aide (field incident technician) will help with this.

- A safety officer (competent and experienced for the hazards present) must be assigned to monitor incident operations and halt them if necessary.

- Responders must stay disciplined in completing assigned tasks. They must not wander or do things at an incident as they see fit. (A strong command presence and in-place accountability system will help to prevent this.)

- Company officers must constantly evaluate the building for the fire’s impact on its “gravity resistance system.” Remember: A building is only as sure as its connections. Load-supporting members may appear safe, but faulty connections (nails into 2 × 4 stringer) will still result in collapse.

- The Incident Commander must have a clear vision of how to manage an incident involving a Mayday and give clear orders following its resolution. Management of the incident must go on for the safety of those still working on the scene.

Chain of Errors

Figure 1. This represents a traditional chain of errors based on the lessons learned from this incident.

Figure 2. This represents a chain of errors working backwards from the traditional chain of errors to find the root cause of the problem.

We were not involved in this incident and do not know the department, so we are making assumptions based on the near-miss report to illustrate our point.

It is possible to see, when simply illustrated, that the behavior (performing unsafe activities) leading to the injury was generally applicable across many different types of responses. The firefighters performing the unsafe behaviors are likely to do so in other tasks based on an “aggressive, take action-oriented organizational culture.” It is also easier to see that the specific symptoms of unsafe behavior and weak incident command are part of a broader deficiency in the organizational culture influencing the behavior. Additionally, this helps illustrate human factors described in

Tailboard Talk: Human Factors. The best part of performing a chain of errors in this manner is that we can also see that there are general behaviors creating an environment conducive to the unsafe behaviors. As a training officer, it becomes more effective to design a program addressing the fundamental behavior of being overly aggressive and the action-oriented culture because it is likely that personnel exhibit these behaviors on every type of call to which they respond (e.g., fires, car accidents, lines down, gas leaks, and so on.). On the other hand, a program designed specifically for the incident described above based on the lessons learned is more specific, particularly the building construction lessons, to a structure fire.

Case Study and Exercise

We would like you and your crew to look at the following near-miss report, #10-0001257, from

www.firefighternearmiss.com. After reviewing the near-miss report, create a chain of errors like the one above to find a root cause. Obviously, you and your crew need to make some assumptions based on your experience and typical fire service culture to work backwards. What would be the contributing factors if this near miss incident had happened in your department?

Event Description

We had a warehouse fire called in for smoke showing. When we arrived, my sergeant told me to pack out and see if we could knock it down. There was flame showing in the back right corner of the building and propane and welding equipment exploding and causing pop-off valves to go off.

We decided to make entry to try to contain the fire and cool off the structure. When we tried to make entry at the side door, it flashed on us. We tried to fight it and back up. While in the doorway, about three feet back, we were still trying to fight it. I then noticed my air was hot and my face piece was starting to melt. We decided it was too late, and

that we should start on a defensive attack.

When we backed out, we started peeling out of our gear

because it was hot. The sergeant told me to stay there and he would be right back. He went to back the truck up due to radiant heat, and I only had on bunkers. Not paying much attention and due to miscommunication, he didn’t return as he said. He thought I had returned to the front.

I then heard a loud explosion and turned to look at the structure. Being only about 15 feet from the building, I saw a cloud of puffy smoke shoot out at me. I pulled my turnout jacket up, and the smoke and fire rolled over me. It then sucked back into the building, and I jumped up and ran. As I was running, I could hear the building falling. I fell about 10-15 feet away after running, and the wall hit right behind me. Needless to say, it scared me half to death.

I was picked up by a couple of rookies

who were trying to get to me and saw it happen. They checked me out and got me away from it as I started to realize my arm had been burned through my jacket when I hid under it. My face had also been burned from the mask when it melted. I was treated and released from the hospital.

Lessons Learned

- This could have been prevented.

- We should have been together in teams of two to move the truck.

- I needed to wear my proper personal protective equipment while that close to the structure.

- We may not have needed to make entry with no lives at stake.

- In that situation, we all learned something from this event.

Discussion Questions

1.

As mentioned in

Tailboard Talk: Near Miss Reporting, firefighters tend to share fundamental personality traits or exhibit certain behaviors including

a.

Sensation seeking

(Jensen, 2005)

b.

Impulsivity

(LeSage, Dyar, & Evans, 2011)

c.

Invulnerability

(LeSage, Dyar, & Evans, 2011)

d.

“Can-do” attitude

(Rosenkrance, et al., 1994)

Did your chain of errors lead to a root cause related to any of these traits or behaviors?

2.

In your experience of reviewing line-of-duty death investigation reports, does the National Institute for Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program seek out the 80-percent causes of accidents, including human factors and/or root causes, or do the reports focus on the 20 percent that have always been the focus?

One possible chain of errors for the near-miss exercise above:

References

Burke, C. S., Wilson, K. A., & Salas, E. (2005). The Use of a Team-Based Strategy for Organizational Transformation: Guidance for Moving Toward a High Reliability Organization.

Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science

, 6 (6), 509 – 530.

Carley, D. A. (2010).

Working Paper on the Development of a Fire Department Into a High Reliability Organization. St. Cloud State University. Fargo, ND: Fargo Fire Department.

Jensen, M. A. (2005).

The Relationship of the Sensation Seeking Personality Motive to Burnout, Injury, and Job Satisfaction Among Firefighters. University of New Orleans, The Department of Human Performance and Health Promotion. New Orleans: University of New Orleans.

Kerwood, S. D. (2008).

Identifying Barriers That Inhibit Institutionalizing Crew Resource Management in Combating Firefighter Casualties. Walden University, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Minneapolis: Proquest UMI.

LeSage, P., Dyar, J. T., & Evans, B. (2011).

Crew Resource Management: Principles and Practices. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC.

Rosenkrance, L. K., Reimers, M. A., Johnson, R. A., Webb, J. B., Graber, J. H., Clarkson, M., et al. (1994).

Report of the South Canyon Fire Accident Investigation Team. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture.

Weick, K. E., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007).

Managing the Unexpected, 2nd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Craig Nelson (left) works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley (right) entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.