By JACK J. MURPHY

During World War II, young Navy Officer Frank Brannigan realized he was unprepared to deal with a fire at the naval base under his command. Needing to understand more about each building, he developed a concept of learning how to prepare to fight a building fire prior to the incident; hence, the concept of the prefire plan was born.

Over the years, the fire service has never completely bought into the preplanning concept. Say “preplanning” to many fire companies who do battle in these buildings, and they respond with fire prevention and code plan reviews.

(1) Even before firefighters enter this building, the windows are “talking” to them. The top three floors may indicate a change of more than a window upgrade, while the old window frames below indicate what? Until a fire company performs a building recon to gather intelligence, fireground safety remains in jeopardy. (Photo by author.)

Lacking Building Intelligence

Before 9/11, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s Firefighter Fatality Investigative and Injury in the Line of Duty (NOISH/LODD) reports forewarned the fire service about gathering preincident plans to reduce fireground death and injury. Even after 9/11, the fire service still lags behind on how to disseminate building intelligence (preplanning) into manageable levels and develop a more informed decision-based fireground battle plan. We must embrace the present building intelligence mobile data technology.

Ask any firefighter if he still has his first cell phone, and he will probably answer “no.” So, why are fire companies depriving themselves of electronic building information card (eBICard) technology to help them tame their fire environment?

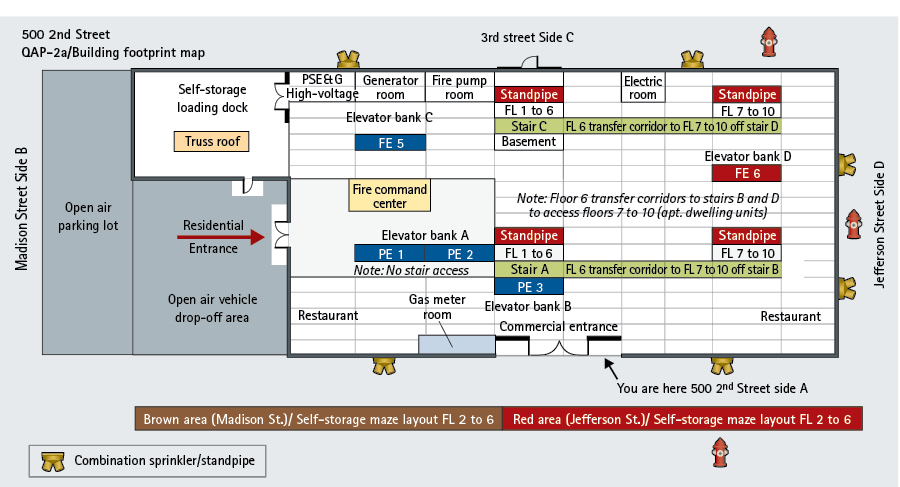

Figure 1. eBICard Building Footprint Map

Reviewing the eBICard building footprint map (QAP-2a) from Side A (red arrow), the incident commander can quickly see what is left and right of the entry door to access stairwells (standpipe/floors levels), elevator banks, utility rooms, fire department connection locations, and truss construction on the lower roof (Side B). Note that the entry doors on floors 2-6 are on the building’s street side and are posted with a color designation area (brown/red) to assist firefighters with searches and potential Mayday calls.

Building Intelligence Rationale

Some sections of the NIOSH/LODD reports recommend that preincident plans be broadcast over the radio system to responders en route to a scene; this familiarizes firefighters with the fire building and its potential hazards. When a fire department relies on mutual aid from adjacent towns to support fireground resource needs, it should also consider the response district’s staffing needs and involve mutual-aid companies in the preincident planning process. Fire departments must conduct building preincident planning surveys to fast-track the development of safe fireground strategies and tactics.

Because of the varying sizes of districts, fire companies prioritize their responses to target hazards and their potential impact on life safety measures. In NIOSH/LODD Report F2013-16, four firefighters lost their lives and 16 were injured in a large commercial building consisting of 26,000 square feet. Two of the five recommendations in the report were for “the fire department to consider implementing a pre-incident program” and a “critical building information system which is available to responding units to enhance situational awareness.” A fire department implementing preincident planning would move it from being a reactive to a more proactive safety position, thus enhancing firefighters’ well-being.

Proactive Fireground Safety Measures

One of the National Institute of Standards and Technology/World Trade Center 9/11 Commission (NIST/WTC) recommendations called for providing first responders with critical building information by establishing and implementing detailed procedures and methods for gathering, processing, and delivering that information to enhance situational awareness. Based on these situational awareness needs, NIST/WTC pushed forth a proactive fireground safety approach that was enacted in codes and standards. These codes and standards provide fire companies with building intelligence for their initial operations while en route to a scene and provide firefighters with safety and precaution information to support the details of the incident as it unfolds.

SMART Firefighting

In the past, prefire plans often ended up in three-ring binders on the office bookshelf, in the chief’s vehicle, or on the apparatus dashboard. These cumbersome paper fire plans are a passive tool compared to an eBICard, which offers quicker, more detail-specific building data. The fireground is a poor environment to make guess-based decisions regarding building knowledge while the incident is rapidly unfolding. In 2013, the NFPA’s SMART Firefighting Building Data Gathering Report clearly advocated empowering a fire company to gather information prior to an emergency. A fire company that collects SMART intelligence data during a reconnaissance mission better enables it to make informed, decision-based strategies and tactics as well as enhances a more effective and safe fireground operation.

One SMART fireground practice for preincident building intelligence is leveraging three manageable levels for a response: (1) Basic (initial operations), (2) Intermediate (how to quickly deploy personnel), and (3) Comprehensive (complete building data) to support the incident as it unfolds. As a situational awareness tool, a SMART eBICard will provide further specific building data that is seamlessly attainable and relevant to firefighter safety in a timely manner. Another prominent feature provides responders with real-time data regarding temporary conditions such as fire protection system impairment and ongoing alteration projects.

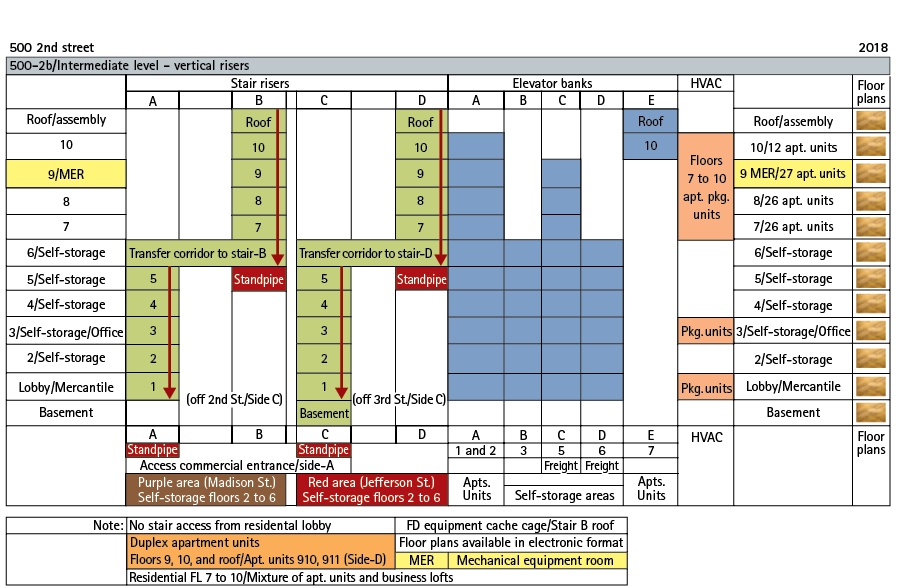

Figure 2. eBICard Vertical Risers Map

eBICard Building vertical risers (QAP-2b) consist of the floor levels; stair risers; the sixth-floor transfer corridor; elevator banks; heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems; floor occupancy load; and floor plans that can also be accessed electronically. The highlights represent several duplex-style apartments that occupy the ninth and 10th floors and roof levels within a dwelling unit.

Adopt a “Know Before You Go” Mentality

Some key building essentials that communications centers can provide to fire companies are water supply, fire protection, and life safety systems as well as any potential threats to firefighters. This “Know Before You Go” (KbyG) tactic regarding critical building information can enhance a fire officer’s “thinking-in-time” process with the initial size-up and empowers crews with their assigned tasks within a specific structure. When the incident becomes a working fire, additional building intelligence information can be provided to the incident commander (IC). By adopting a KbyG mentality, fire companies can gather relevant building intelligence and distribute it into the three manageable levels during a fireground operation, enabling them to better know the buildings in their response districts.

Performing a building recon necessitates gathering information about the structure’s exterior and interior; this is called “intelligence.” Having critical data about a building’s features such as floor layouts, exits, construction features, and so on enhances fireground strategies and tactics. It is beneficial to rotate each work shift/tour on a building cycle for the same address; this enables firefighters with “new eyes” to observe something that a previous crew may have missed. For example, during a building recon training session walk-through of a hospital complex, the third crew noticed a standard-size door high up on the wall with a fixed ladder below the door saddle; on further investigation, this door led to an exterior open space. Shortly after the firefighters recognized the door as a potential hazard, a durable sign was affixed to its exterior that read “SHAFTWAY WITH FIXED WALL LADDER” to warn firefighters of the hazard beyond the door.

Individual Building Battle Plans

Gathering individual “battle plans” for any building, particularly high-rises, large structures, and building complexes (i.e., malls, colleges, and so on), can be an eye-opener for firefighters. For example, consider a 10-story fire-resistive construction building with a mixed occupancy (business floors 1-6, residential floors 7-10) and separate entrances. Once you are inside this structure, many “red flags” (mental caution signs) will arise regarding firefighters accessing the upper residential floors as well as occupant evacuation. In photo 1, the building shows four separate stairs that do not directly connect to one another or run the full height of the building from floors 1-10.

After gathering building data, a building footprint map (Figure 1) can provide the first-due fire company’s intelligence for initial operations such as how to access the fire command center off Side B and how there is no stairwell off the residential lobby area; this can be indicated as a note (e.g., “No Access Stairs”). Also, fire department connections are a combination sprinkler/standpipe system, so access to the lower stairs (Stairs A and C/Floors 1-6) are off Side A and can lead to a sixth-floor transfer corridor that directs firefighters to the upper stairs (Stairs B and D/Floors 7-10) as shown on the map.

If the IC has predefined initial operational guidelines ahead of time, he can deploy personnel within 30 to 60 seconds of their arrival. Taking note of this, he may develop the response strategy for the first-due company to go to Side B at the fire command center and the second-due company to report to Side A to access the building stairs. Also in Figure 1 are floors that have a maze-like layout (e.g., floors 2-6) and house multiple self-storage sheds. These floors can quickly disorient searching firefighters and can hamper the upper apartment occupants, who may stray off course as they use the transfer corridor onto the sixth-floor maze area.

A vertical building riser diagram (Figure 2) further supports the building footprint map by featuring Stairs A and C, which go from floors 1-6, while stairs B and D go from floors 6-10. The sixth floor is one of the red flags that the fire company observed as a horizontal transfer corridor level that connects stair A to B and stair C to D.

Fire departments can place the building intelligence captured during the recon process into an electronic database system for rapid retrieval the next time current and future firefighters respond to this building complex. This eliminates the process of “reinventing the wheel” each time members respond to this building.

If These Walls Could Talk

Because the fire service is a supportive organization, a department’s mission statement should include preincident building intelligence to further safeguard firefighters as well as occupants. You can manage eBuilding intelligence easily with three databased levels; these data help inform fire companies on how a building can react during a fire, how the fire may develop and expand, how smoke will travel and its effects on occupants and firefighters, how building components and layout impact fire/smoke spread, and how the fire protection systems work.

Also consider all-hazard (nonfire) behavior as it relates to external/internal building risks for man-made threats (bomb threats, active shooters, utility failures, and so on) and natural disasters (hurricanes, tornados, earthquakes, and so on). Building features and future construction techniques will continue to challenge the fire companies. However, if your department adopts a KbyG mentality, firefighters can get out in front of their work environment.

A municipality may pump money into a communications center to handle 911 calls and dispatch fire units, but many communications centers still lack the ability to easily retrieve “big data” building intelligence, push out into the field with three manageable levels of electronic data to help commence operations, quickly deploy fireground personnel, and support the incident as it unfolds. Providing the fire service with individual eBICard building “battle plans” to function as seamless emergency preparedness technology is a solution that is available today.

Author’s note: Some excerpts of this article are from High-Rise Buildings: Understanding the Vertical Challenge, Chapter 4: “If These Walls Could Talk” by Jerry Tracy, Jack J. Murphy, and James J. Murtagh (PennWell).

References

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Line-of-Duty Death Report F2013-16, Recommendation No. 4 (pg. 53) and Recommendation No. 5 (pg. 55).

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)/World Trade Center (WTC) 9/11 Commission

National Institute of Standards and Technology/World Trade Center 9/11 Commission

NFPA 1620, Standard on Pre-Incident Planning (2015 Edition).

NFPA SMART Firefighting (2013).

NIOSH/LODD Report F2013-16 (7/15/2016)

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face201316.html.

United States Fire Administration. Transforming Your Department’s Response with Electronic Pre-Incident Planning, No. FM—2012-1 April 2, 2012. www.usfa.fema.gov/nfa/coffee-break.

JACK J. MURPHY, MA, is the chairman of the New York City High-Rise Fire Safety Directors Association. He is also a fire marshal (ret.) and a former deputy chief and has served as a Bergen County (NJ) deputy fire coordinator. He serves on the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) committees for the High-Rise Building Safety Advisory and NFPA 1620, Pre-Incident Planning. Murphy also represents the International Association of Fire Chiefs on the Northeast Region Fire Code Work Group. He is the author of many fire service articles and authored a field handbook on Rapid Incident Command System and co-authored “Bridging the Gap: Fire Safety and Green Buildings.” He is a Fire Engineering contributing editor and PennWell Fire Group advisory board member. He received the 2012 Tom Brennan Lifetime Achievement Award.